Jamila's Article Book

Jamila’s Article Book: Selections of Jamila Salimpour’s Articles Published in Habibi Magazine, 1974-1988

Background

Belly dance as we know it today evolved over centuries and represents a rich tapestry of cultures and influences. From childhood, Jamila Salimpour was fascinated with this dance form, first learning about it from her father who served in North Africa during his tenure with the Sicilian Navy. She delved into the deep history of belly dance, tracing its roots, and exploring its cultural significance.

Origins

Jamila strongly believed that the origins of belly dance could be traced back to ancient civilizations in the Middle East, North Africa, and parts of Asia. Dance was an integral part of religious rituals and social celebrations in these regions. The movements and gestures associated with belly dance were believed to invoke the divine feminine and were often performed by priestesses or women in religious ceremonies. The rhythmic undulations and fluid hip movements were considered a form of communication with the gods and a celebration of life and fertility.

Ancient Egypt

One of the earliest depictions of belly dance can be found in ancient Egyptian artwork. The Egyptians revered dance as a form of artistic expression and used it to celebrate important occasions such as weddings and religious festivals. Paintings and sculptures from this era depict women with gracefully undulating torsos and fluid hip movements, which Jamila considered precursors to modern belly dance. She found great significance in the study of ancient gods and goddesses as the placement of these deities represented cultural views of the time. Anat, the Egyptian mother of gods, became an inspiration for Jamila’s Mother Goddess dance. This was the dance that served, and continues to serve today, as the opening performance for Bal Anat, the longest-running belly dance show established in 1968. The Mother Goddess, sometimes called the Mask Dancer, was Jamila’s homage to what she considered the origin of belly dance.

Mesopotamia

She also was convinced of the dance’s roots in ancient Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq), where it was known as the “Dance of Ishtar,” named after the goddess of love and fertility. The dance was an integral part of temple rituals and was believed to bring blessings of abundance and fertility to the community. Other cultures had similar goddesses, and Jamila studied them all in detail.

Fusion of Styles

As centuries passed, belly dance evolved and absorbed influences from various cultures. The Arab conquests in the 7th and 8th centuries spread Islamic traditions throughout the Middle East, leading to the fusion of Arab, Persian, and North African dance styles. Performing cultures like the Ouled Nail and Ghawazee were often written about by Western travel writers in derogatory and colonialistic terms, but Jamila preserved through such books to try and find the truth.

Little Egypt

The 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago featured a belly dance performance by a popular dancer named Little Egypt. This sparked a fascination with Middle Eastern culture and dance in the Western world, leading to the inclusion of belly dance in vaudeville shows and traveling circuses. Jamila saw some of these depictions in her childhood. While she knew they were not “the real thing”, she wondered what, if anything, of the real dance could be found in these caricatured performances.

20th Century

In Egypt, in the early 20th century, a more theatrical style of belly dance emerged, influenced by Western ideas of entertainment. Badia Masabni featured this style in her nightclubs in Cairo. This style, known as “Raqs Sharqi” emphasized elaborate costumes, intricate choreography, and the use of props such as veils and finger cymbals. Legendary dancers like Tahia, Carioca, Samia Gamal, and Naima Akef were icons of Egyptian belly dance during this period. The burgeoning Egyptian movie industry put these dancing stars on screen, and Jamila saw these movies when they came to Los Angeles.

In the US

In the United States, belly dance became popularized as a form of exercise and self-expression. Pioneers such as Jamila Salimpour, and Ibrahim Farrah introduced the art form to a broader audience, helping establish belly dance as a respected discipline. Jamila researched and taught her Vocabulary of step families, representing steps from professional dancers and everyday people. Included in that Vocabulary were also some of Suhaila’s earliest research in folkloric steps as well as her study and pioneering approach to understanding and performing movements.

Habibi Magazine

Jamila wrote about her studies in Habibi Magazine, sharing her knowledge and findings with other dances to encourage them to continue her investigation work. She wanted to present a foundation that would help support the art form. And here we provide the selections from Jamila’s Article Book: Selections of Jamila Salimpour’s Articles Published in Habibi Magazine, 1974-1988, published by Suhaila International in 2013.

The Article Book is not a complete history or story of Jamila or belly dance, but it is a collection of some of her more interesting and popular published articles. These works include Jamila’s personal history, dance experiences, research, events, and friends. We now make these available for online belly dance learning and research.

About this Book

Originally Introduction from Jamila’s Article Book

Teacher, researcher, and innovator Jamila Salimpour was definitely the right dancer in the right place at the right time. Her innumerable contributions to belly dance have influenced millions of dancers around the world, even if they don’t know it.

As a child, Jamila was fascinated by Middle Eastern dance, and as she became an eminent figure in belly dance herself, she explored its roots, history, and dance vocabulary, seeking out every book, film, photo, memento, and tidbit that she could find that related in any way to what Middle Eastern dance. For nearly a decade she published her research, observations, and thoughts in the long-lived belly dance publication Habibi.

Bob Zalot

In 1974, Bob Zalot began the production of Habibi magazine in California, making it one of two major publications focusing on Middle Eastern dance in the United States (the other being Ibrahim Farrah’s Arabesque, published in New York). Knowing that Jamila was already considered a matriarch of belly dance, Bob asked her to write regularly for his publication. Drawing from her wealth of collected research, Jamila regularly contributed articles to the magazine for over a decade.

This Article Book

The book you hold in your hands now is an edited volume of select articles that Jamila wrote for Habibi magazine. Ranging greatly in content from factual research to local gossip, she also shared passages from books not easily available to Habibi’s readership; wrote reviews of music, films, and dance events; and often added her own observations and insights. She conducted interviews, related her personal history, and told stories about her travels, experiences, and students.

In addition, film footage of dancers, both in the United States and abroad, was scarce, so Jamila often wrote about the details of the performances she saw in person or on film, to give her readers a sense of each dancer’s style, signature steps, and essence. Often, articles such as Jamila’s were a dancer’s only source of information about Middle Eastern dance and music.

Images

Amongst the artifacts Jamila sought relating to Middle Eastern dance are a wide variety of images. The majority of images in this volume are from Jamila’s personal collection. They range from authentic photographs of dancers and women to fantasy paintings. For instance, many of them Western romanticizations of Middle Eastern women from the late-1800s to the mid-1900s. Regardless of their authenticity, these images influenced the dance both in the early Egyptian and American movie industries as well as the greater belly dance community worldwide. Today, they continue to influence dancers.

Presented with the contemporary belly dance student in mind, this collection is meant to transport the reader back to the time in which Jamila wrote the articles and to give the reader a glance inside Jamila’s head, so to speak. As you read, remember the time frame in which Jamila wrote them: a time of live bands in smoky nightclubs, 78 rpm records, and reel-to-reel tapes. There were, of course, no DVDs, online video services like YouTube, or digital music downloads.

About Jamila Salimpour

Jamila Salimpour’s lifelong fascination with Middle Eastern dance first began early. Her father told her stories of the dancers he saw when stationed in Egypt during World War I. When Jamila moved to Los Angeles at age 19, her fascination grew. As a result, she began researching and collecting anything and everything she could related to the dance.

Egyptian Films

At the same time, Egypt’s film industry thrived. Many movies featured musical song and dance numbers, often highlighting a solo belly dance star in the lead role. Several months after the films were released in Egypt, they were released in the United States. When they came to her local Los Angeles theater, Jamila would see every movie that she could, usually more than once. First, she tried to remember as much detail about the dancers as possible. Next, when she returned home, she emulated their movements, steps, and stylizations.

Live Performances

In addition to her multiple viewings of Egyptian films, she attended local performances of musicians and dancers, took music lessons on various Middle Eastern instruments, and sought out and interviewed anyone she could to increase her knowledge. She was a voracious reader, jotting down important passages and citations by hand. In addition, she perused antique stores, thrift shops, and estate sales to find anything she could that related to belly dance. Steadily, she gathered together her research, organizing her materials.

Creating a Methodology

In 1949, Jamila began teaching belly dance, fine-tuning her teaching methods for belly dance and finger cymbals, and sharing her knowledge with her students. In the 1960s she arranged performance venues for her thriving student body in San Francisco. Thus, she created opportunities for dancers to perform professionally.

Bal Anat

In 1968, she began and directed Bal Anat, now considered to be the first “Tribal Style” belly dance troupe. Her students performed at the Northern California Renaissance Pleasure Faire in assuit and coin belts during the day and then would perform in bedlah and chiffon skirts in the clubs at night. Several of her students developed successful careers of their own as professional belly dancers in the Middle East and Europe. As the 1960s ended, Jamila was considered a matriarch of the dance.

Teaching

In the late 1970s, Jamila began teaching weeklong workshops to bring dancers together for instruction, shopping, and performing. With the help of dedicated students, her format was documented in a manual published in 1978. Soon thereafter, her format was presented and taught by Suhaila Salimpour in four volumes on VHS tapes.

Legacy

Her legacy lives on in nearly every belly dancer in the United States, as well as countless dancers around the world. Her terminology for belly dance steps, such as “Basic Egyptian”, “Maya”, and “Turkish Drop” have become standard, and the style and look that began with Bal Anat has evolved into a wide variety of approaches and stylizations.

Step back in time, and enter Jamila’s world…

From Suhaila Salimpour:

This book is dedicated to my mother for her years of research in this art form. Who knew that all the garage and estate sales and all the used book and antique stores would weave together such inspiring research. Being dragged on all these adventures as a kid, I took it all for granted thinking that everyone had a mom that was part detective and part archaeologist. Now I’m so grateful for everything I learned in that process and for all the research that was done.

I also want to thank my friend, Vonda. Every brainstorming breakfast on this project brought the articles back to life. Your appreciation for my mother’s work allowed me to deepen my understanding of them, as well. Having had someone to share this adventure with made each step so much more fulfilling; it was a joyful collaboration between us. You have been a blessing to the Salimpour family and a gift to the belly dance world.

The Articles

Jamila’s beginnings in New York City as the child of Sicilian immigrants. After losing her mother at an early age, she eventually left home to join the Barnum Bailey circus, working with elephants.

Jamila moves to Los Angeles and finds lodging in the home of an Armenian family that immigrated from Egypt. It was here that her study of the dance first flourished.

Jamila begins her belly dance studies, learning from watching the great Egyptian belly dance film stars and from dancing with women from the Middle East.

Jamila begins her dancing career with a new costume and encouraging audience, yet encounters her first scoundrel. However, she found support in the community of women.

Belly dancing was becoming more popular, and agents contracted with Middle Eastern dancers to come to the United States and perform at various clubs. One of the first highly successful clubs was the Greek Village.

With her knowledge of jewelry making, Jamila creates her first coin costume, immortalized in the illustration done by Bob Mackie. This coin belt trend was incredibly popular and still continues today.

Tabora Najim and the Turkish Drop.

Jamila continues her research of steps and step families, carefully documenting and chronicling where, how, by whom, and why the steps are performed.

Jamila recounts her early experiences with belly dance and the evolution of the dance on the West Coast, where cultures were melding as were the belly styles from each culture.

Raqs Sharqi: The “Long” and “Short” of It.

Jamila discusses how belly dance performance sets began as shorter presentations. Eventually, sets grew into constant dancing without breaks in an effort to keep customers interested.

Customs, Conflicts, and Casualties.

Due to financial and cultural differences, tensions arose between Jamila and her Persian husband.

Jamila explains the origins of Bal Anat, her legendary belly dance troupe that started at the Renaissance Pleasure Faire. A faire traffic jam resulted in what has become the longest-running belly dance troupe, established in 1968.

Omar was an incredibly talented Egyptian musician who developed his own method for playing quarter tones on his guitar. He tragically died young in a car accident.

He was the owner and manager of The Fez, a popular nightclub in Hollywood that contracted top belly dance talent out of Egypt. Also a musician, he provides his candid opinion of dance and music in this interview.

Ahmad was a Lebanese dancer raised in Canada. Jamila considered him one of the greatest artists she knew personally. For example, she valued his intricate nuance and sentiment in and for belly dancing.

Inspired to provide visiting dancers a greater experience of what the San Francisco Bay Area provided for belly dancers, Jamila created the Faire.

As part of an Egyptian cinema event involving many of the great actors and actresses, Nagwa Fouad, the great Egyptian belly dancer, performed.

Belly Dance History

Middle Eastern Martial Mime in the Sword, Stick, and Cane Dance.

Jamila gives a brief accounting of her research from prehistoric cave drawings to more recent days. Significantly, she notes the influence of martial art rituals on belly dance.

Pantomime and Party Tricks.

Jamila discusses her efforts to find the “real” dance through her research from books, documentaries, film clips, and more. She documented it all, looking for connections.

Women Musicians in the Middle East.

Jamila gives context to how instruments and dancing were affected by other cultures throughout the ages, giving rise to the instruments used in belly dance today.

Uncovering the Mystery Behind the Veil.

Belly dancers use the veil as a prop for entrances and taqsim. However, the veil has a much older and deeper meaning in Middle Eastern culture and religion that varies from region to region.

Bring on the Dancing Boys.

While she originally would only teach women as that was what seemed culturally correct, Jamila found historical precedence for teaching men. Therefore, this research opened the door for male dancers to learn and thrive.

Belly Dancing at the American Centennial.

Jamila researched the history of Middle Eastern music, dress, and dance as depicted in famous exhibitions. Examples include the 1851 Crystal Palace Exhibition in England and the 1876 Centennial International Exhibition in the United States.

Gunfighters and Ghawazee.

As a result of her research, Jamila learned about the portrait of Fatima, an Egyptian dancer. Fatima performed at the notorious Bird Cage Theatre in gunslinging Tombstone, Arizona, in 1882. This was about a decade prior to Little Egypt’s debut at the Chicago World’s Fair.

The Legend of Little Egypt.

At the time of Jamila’s research, there was much mystery about who was the real Little Egypt dancer. For example, was there really one woman called Little Egypt, where was she raised, and what was her culture?

The Orientalists.

Jamila endeavored to find any truth she could acquire from Orientalist paintings and writings, trying to separate someone’s imagined fantasy from what was real.

Danse du Sabre Reincarnated.

Using a Gerome etching as her inspiration, Jamila developed a sword dance. As a result, she brought the martial mime element into Bal Anat and the greater belly dance world.

Bakst the Orientalist, Father of Costume Design.

Jamila explores the work and influence of Leon Bakst, the Russian costume and set designer. He was famous for his elaborate work and colorful costume sketches with the Ballet Russes dance company.

Image of the Middle Eastern Dancer at the Turn of the 20th Century.

Jamila chronicles the change in Middle Eastern dance as it emerged into the 20th century including influences and correlations.

Portrayal of Belly Dance in Hollywood.

Jamila discusses how belly dancers and belly dancing were represented in Western movie films. For instance, stereotypes included romances where women are saved from a life of drudgery by a handsome sheik. Additionally, dramatic storylines frequently featured treacherous dancing femme fatales.

“Danse Orientale”, Choreography, and Egyptian Folkloric Dance.

Jamila explains how Egyptian folkloric dance had a significant influence on the trajectory of Egyptian belly dance stylization, choreography, and costuming.

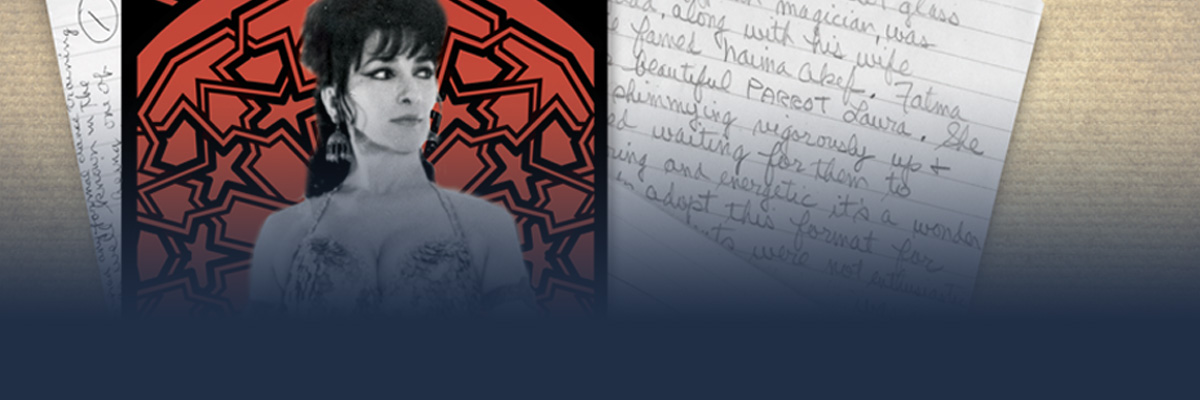

Fair Ladies of the Forties.

Jamila describes three of the great belly-dancing Egyptian cinema stars who inspired her. These women were Tahia Carioca, Samia Gamal, and Naima Akef.

Dance of Yesterday as Compared to Today.

Jamila discusses what someone can discover about belly dance when reviewing old documentaries and movie films featuring Middle Eastern dance.

Sohair Zaki.

Jamila describes the beautiful movements of this famous Egyptian belly dancer who was known for her signature down hips. Suhaila researched these and brought them into her mother’s Vocabulary, initially called Singles on the Down.