Many of us who viewed Egyptian dance films during the 1940s were unaware of the power and destruction of the Egyptian censors. Large segments of dances were edited out, and only the more sedate portions were left intact. Motion pictures undoubtedly made an incredible impact on the entertainers who made their living in Vaudeville houses or casinos. It can only be assumed that a dancer, although she might have been an incredible dancer, might not have been chosen to be a star because she was not photogenic. On the other hand, the girl who was photogenic and not necessarily a good dancer, might have been the one chosen to star.

So, what are we looking at in the old-time movies? We must consider that we are watching a dance form that was generally repressed and not acceptable to so-called “good” families. In the past, a dancer might only be hired for festivals and private parties, but in movies, she would be viewed by the masses. If a dancer was noted for her lascivious delivery or spectacular gyrations (or, as I’ve heard was often the case, her dance in the nude), she was certainly not the one to be chosen for a “family” movie. And yet, she might have been the better dancer.

In early Edison movie documentary from the Chicago World’s Faire in 1893, a dancer was filmed who gyrates uninhibitedly, unbelievably, in an ecstatic solo. I don’t believe I’ve ever seen anyone dance with such abandon before or since. I myself have seen dancers in person with movements that have yet to be defined.; however, I never saw these movements in any of the old Egyptian movies.

So, has the dance changed since the turn of the century and the advent of movies? I think so! I think what might have been viewed in private was beyond description, and dancers of old were more noted for muscle control feats visible only in the salons of the wealthy. The movies might have even set a precedent for prudery which respectful dancers emulated. In an attempt to appeal to a broader but conservative public, the movie producers probably asked the dancers to “tone it down” for fear of alienating the family which, to the bottom line, would simply mean bad box office sales.

When I first saw Tahia Carioca and Samia Gamal in the early films, it was truly a time of innocence. Never before had so many people seen these Egyptian mega-stars except in movie theaters. Now, forty-one years later, I look back and reminisce; but I also realize that what I saw on the screen might not have been a true representation of uninhibited dance. Just as today, if a dancer shows her bare midriff, arms, and legs, she will not be able to perform in most parts of Saudi Arabia, nor will her dance videos be permitted to be sold unless she “covers up”. It wouldn’t be difficult to conclude that this kind of suppression would result in a change of attitude toward the dance and in a stifling of certain movements that might raise conservative eyebrows.

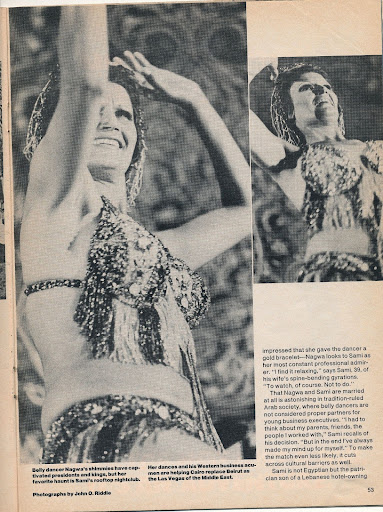

In the films of the forties, Tahia Carioca was modest. She exuded an Egyptian ideal in face and form. Whatever she danced did not seem imitable; even if you could move like her, you could never look like her. Samia Gamal had a very unusual presentation. Her body would twist like the hand on a metronome with half circles, mostly front. In her interpretation of the song “Zeina”, her hips flutter the staccato of the violins, defying analysis. She loved to play with her skirts. Among her many dance signatures was her petulant pout. It was the era of the screen goddess; she was one of the dancers who reigned almost as a deity.

Undoubtedly, the two best-known dancers were Tahia Carioca and Samia Gamal. No dancer who came after them made such an impact on the public. But, they were not really featured as dancers. The emphasis was shifted from dance (which was presented as incidental) to acting. Were there any other films about oriental dancers? If we consider the film Tamer Henna in which the dancer Naima Akef plays a dancer, again we must take into consideration the audience and the censor. So the movies, while entertaining us, also deprived us of the total experience of what they felt was necessary censorship for our own moral well-being. But in their limited way, the old-time movies are important for viewing.

Today we have much more material from which to draw. Whole dance sequences of Mona Al-Said, Fifi Abdo, Nagwa Fouad, and other dancers of their stature will ensure future generations of dancers with a reference for comparison and growth. But again, glamour and a large amount of Western influence have altered the ethnicity of the dance as we see it today. I think some of it is for the better and some not. Where I think it is for the better is in the general carriage of the body. It seems that old-time dancers, except for limited arm and torso movements, did not have a body carriage that would sustain a graceful look. In some sequences of baladi, more than one dancer played finger cymbals with palms down with elbows bent almost at shoulder level. Oh my! Another recent full-length dance video shows one of the “greats” doing the same thing. I guess the importance of finger cymbals as a percussion accompaniment has waned over the years. Suhaila and I insist on being able to move arms up and around, crossing over singly or together, while playing finger cymbals. We believe that anything you can do with your arms without cymbals you must train yourself to do gracefully with cymbals. Of course, the musical must be suitable for cymbals and not be dominated by them constantly.

A lot has changed in the dance, but I think a growing awareness has taken place in bringing back to the dance that special hipwork that is the individual trademark of danse orientale. It was there in the old-time dancers, and it should be emphasized and encouraged in future dancers. Also, up-and-coming musicians should be inspired to revive the native instruments which seem to be more compatible with the music. What great sounds and compositions used to be heard in the 1940s. Nowadays it takes a lot of searching to find that piece that makes you want to “grind coffee”. Back in the forties almost every song or musical was hot. That’s why I never tire of watching my videos of the old-time greats.

This article was published in Jamila’s Article Book: Selections of Jamila Salimpour’s Articles Published in Habibi Magazine, 1974-1988, published by Suhaila International in 2013. This Article Book excerpt is an edited version of what originally appeared in Habibi: Vol. 10, No. 2 (1987).