Foreword from Jamila Salimpour

Alphabet

Middle Eastern dance has a vast movement alphabet characteristic of the culture. When putting together the letters to form simple words, a dancer’s body learns how to express these words.

The dancer’s study and practice lead to a command of the language that shows an extensive movement vocabulary characteristic of the culture. Indeed, further study unlocks the potential to express a seemingly effortless and sophisticated technique with expression in performance.

As the form evolves and the dancer becomes more skilled, the level of expertise can reach unbelievable heights. However, this can only be achieved by deepening a relationship with the dance language and–very importantly–with the culture and music from which this dance comes.

In time, a logical blend results wherein the dancer’s movements complement the music and vice versa. As the dancer develops, the mind understands what the body is expected to achieve. The goal is a synthesis of physical skill, mental awareness, and individual creativity and expression.

Where to Begin

I studied, documented, and did my best to document steps, stepfamilies, and stylizations. However, Suhaila really knew how to create it as a format, to see the connections, and to explain it in ways that students could comprehend.

When students ask where to start learning, I always say to start with Suhaila’s format basics. Using her methodology and perspective, learning the posture and movements from her format is your best first step to this dance form. Then, learn the Salimpour Vocabulary using Suhaila’s method as your base.

Suhaila has always respected my work and placement in our dance community. But the truth is that she contributed nearly half of the Vocabulary by the late 1970s. She undoubtedly contributed more than half upon my request. For example, she included the Persian, Khaleegi, and Debke families. She is an integral part of the Vocabulary and its development. In addition to her contributions, she has given it foundation and longevity.

I have been surprised by the dancers who choose to separate my work from Suhaila’s. Some contact me with pride because they will only study my vocabulary and not Suhaila’s format. These statements prove they do not understand the work yet because Suhaila is an integral part of the Vocabulary and its development.

Salimpour Vocabulary

Here I present to you a collaboration of mother and daughter. The Vocabulary is our shared love-letter to the incredible culture and music. This is not my Vocabulary, but our Vocabulary: The Salimpour Vocabulary.

Jamila Salimpour, September 2, 2017

Vocabulary Introduction

When Jamila Salimpour began teaching belly dance in 1949, she started compiling and codifying a vocabulary of movements which she organized into step families. She based these step families on her study and observations of professional dancers in Egyptian films and those with whom she worked in the nightclubs between the 1930s and 1960s.

In addition, she included steps and stylistic elements from Algeria, Egypt, Iraq, Morocco, Tunisia, and Turkey. Suhaila also contributed by adding Home Position, isolations, locks, and several steps. such as isolations, locks, and folkloric steps — to complete the vocabulary as presented in this new volume.

“In my early investigation of belly dance, I never came across anyone with valid credentials who had names for steps or patterns such as those used in ballet. For a lasting understanding and appreciation of this dance as an art form, a standard vocabulary must develop which would adequately describe steps, transitions, variations, combinations, and interpretations.

Information must be made available for those who want to investigate folk customs and ethnological evaluation of styles and steps. If the level of performance is going to be raised, the why’s and how-to’s must be answered.

Just as ballet studios may specify for instance the Cecchetti method of instruction, so must the danse de ventre specify any one style that adheres to the more traditional style.”

Except from Jamila Salimpour’s article in Habibi magazine, Volume 3, Number 7, 1976.

Vocabulary Impact

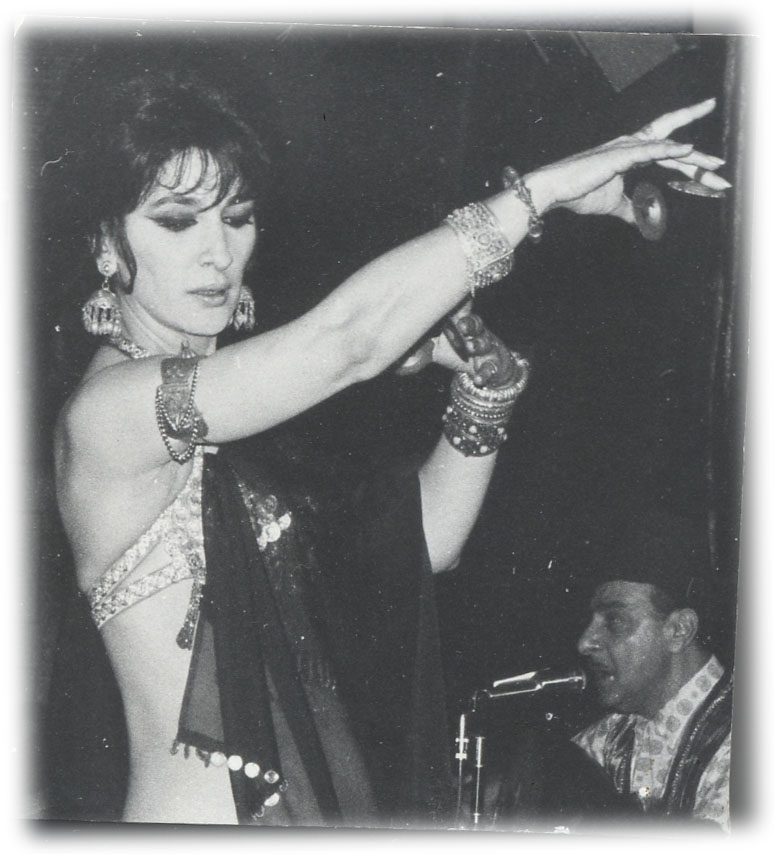

Jamila’s teaching and cymbal formats were already known in much of the United States, but the success and popularity of Bal Anat brought it to even wider attention. Nearly every belly dancer in the United States, as well as most other areas of the world, has been influenced by Jamila Salimpour and Bal Anat.

The Original Manual

The original manual was first published in 1978. As stated in the original: “The Jamila Style is a Verbalization of a composite of styles as put together and taught by Jamila. . .a verbalization which is unique in its simplicity of communication.”

She observed the techniques and styles of the dancers she worked with from several Middle Eastern cultures including Algerian, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Morocco, Syria, and Turkey. Although most of the vocabulary had been presented in various class handouts over the years, the manual was the most complete representation.

Two of Jamila’s devoted students, Aida Al-Adawi and Ghanima Gaditana, assisted with the first manual which was written for one of Jamila’s workshops in the 1970s. The resulting product became used as the official manual with no further edits. Both women were integral members of Bal Anat and assisted Jamila in teaching her vocabulary. Their experience and dedication are largely responsible for the completion of the original manual.

Credit and Accreditation

“Distinctive names, which identify body mechanics such as Algerian, Turkish, Arabic, and Egyptian, can mentally separate style and movements and aid in simplifying the learning process.

Whatever influences I have had, I feel it is only fair to give credit to those dancers with whom I had the good fortune to work. To the best of my ability, I give them credit so that my students and my students’ students will remember some of the pioneers who paved the way for this dance to become popular and to be accepted as an art form.

I hope that someday all the teachers can meet and exchange ideas as to how to communicate better to their students by using a standard verbalization which would have the flavor and character of the Middle East.

We can look forward to, perhaps, an accredited board. . . . There is still much to do, but I feel there has been progress and lots of intercultural exposure.”

Except from Jamila Salimpour’s article in Habibi magazine, Volume 3, Number 7, 1976.

How to Use This Book

This book is a study guide to be used along with live class and workshop instruction in the Salimpour Belly Dance Vocabulary. However, this book is not meant to be used as the primary learning tool and is written specifically as a supplementary resource.

The Vocabulary comprises step families, based on Jamila’s original organization. When learning a step, think of it as being part of a larger group of related movements, as opposed to having a single fixed definition.

To truly understand each step, learn the entire family and research other Vocabulary steps to discover connections and commonalities between them.

Why This Book Exists

Suhaila Salimpour, Jamila’s daughter, grew up learning, contributing to, and teaching the Vocabulary as well as studying other dance forms such as ballet, jazz, tap, and various ethnic dance disciplines. Together with what she learned in jazz and ballet, Suhaila broke down belly dance steps for herself by identifying muscular contractions, downbeats, and timing.

Through this approach, she found that she could layer any movement with any other movement. As a result, each layer could have different timings and downbeats, and hip movements did not necessarily have to coordinate with specific foot patterns.

Jamila’s Support

Jamila supported Suhaila’s innovative approach because she believed this breakdown was necessary for the dance form to grow. So, in 1979, Suhaila began consciously creating and documenting her own vocabulary, which revolutionized how the dance form is taught, learned, and understood today.

In 1992, Jamila asked Suhaila to rewrite the instruction for the Steps and Step Families, which led to Suhaila formalizing and solidifying her own method and certification program. With Suhaila’s format firmly in place, Suhaila had the formal structure to revisit Jamila’s original manual, producing the updated volume available today.

The Vocabulary comprises step families, based on Jamila’s original organization. When learning a step, think of it as being part of a larger group of related movements, as opposed to having a single fixed definition.

To truly understand each step, learn the entire family and research other Vocabulary steps to discover connections and commonalities between them.

Suhaila Salimpour Format

Students are expected to have a basic working knowledge of Fundamentals 1 from Suhaila Salimpour’s format.

Defaults and Reverse

For each step, the standard defaults for direction, timing, downbeat, etc. are described in the basic definition. The term “reverse” in this vocabulary, unless otherwise noted, is the exact mirror image (i.e., reversing right and left) of the default. (As some steps alternate right and left by definition, not all steps have a reverse.)

The default of a move represents the most basic form of a move, but it may not represent the earliest Salimpour version. Specifically, a default for each move was designated for the purpose of providing the student a “basic” form. From this root, a dancer can build to understand variations in the context of and relation to the default. Correspondingly, notes have been included that indicate the variations used by Jamila and Suhaila.

Variations

Each step can be varied in timing, downbeat, direction, and layering. Focus carefully on the root of the movement and the default. Once you know a move thoroughly, both technically and stylistically, you can vary the move responsibly.

The Clockface

Jamila used a clock to direct students in body placement. Standing in Home Position, imagine you are centered on a clock face. You face 12 o’clock, and 6 o’clock is behind you; your right side aligns with 3 o’clock, and your left side aligns with 9 o’clock.

Traveling in a Circle

In Jamila’s classes, students travel in a counterclockwise (CCW) circle around the dance floor, with the instructor in the center of the room. The circle has no beginning or ending point. As you travel in the circle, you learn spatial relations in context to the other dancers in the circle. Hence, as a group, you also learn to connect energetically.

When moving in a circle, facing “front” or 12 o’clock means facing the direction you are traveling. This means that your personal front or 12 o’clock will change based on where you are traveling in the circle.

“Jamila designed and created her format to enable students to improvise to live music–that was the seed. Teaching her students to improvise was the point. It was her purpose for the Vocabulary.”

Suhaila Salimpour

Improvisation

Jamila’s steps, especially within specific families, flowed from one to the next, facilitating improvisational dance within the context of the vocabulary. As Jamila stood in the center of the circle, she called out the next step.

Students could not always hear the worded commands. Therefore, they learned the inflection and cadence of Jamila’s voice for specific steps as well as visual clues to help them transition into the next step.

As soon as students learned a move, Jamila encouraged them to improvise their own arm and cymbal patterns. In many cases, Jamila did not set default arm patterns until she began creating choreography for Bal Anat in the late 1960s.

Riffing

Jamila studied and documented her step vocabulary by watching and studying dancers. Additionally, she carefully selected music to represent the exact sentiment and stylization. She would dance, practice, improvise, and riff until she was able to isolate the desired step and perform it consistently.

Riffing: improvisation based on a default step or phrase by experimenting and personalizing with variations and differences while still keeping the theme step or phrase in mind.

Suhaila Salimpour

Jamila felt the circle format of her classes provided a supporting frame for this type of improvisational work. The circle promoted continuous movement as there is no beginning or ending to the circle. By watching and hearing queues, students danced and traveled the circle while figuring out the steps without stopping.

The Role of the Circle

Once students learned a step, they were encouraged to improvise and riff with the step while maintaining the same sentiment and stylization as the music and default step dictated. Jamila felt that moving in a circle with other dancers taught students spatial relations. Furthermore, she felt the circle promoted an energetic bond for the class members.

Although she encouraged variation and riffing, Jamila rarely reversed her steps. If she taught a step as always starting on the right foot, then she never broke down the reverse starting on the left foot. When she began assisting her mother in class at the age of 9, Suhaila broke down the reverses and variations in addition to adding steps to the Vocabulary.

Influences

Several people influenced Jamila’s vocabulary leading up to and during the 1970s, when the vocabulary was finalized in the present form. Jamila documented her vocabulary first by observing professional dancers from the 1930s-1960s.

She also named moves after specific dancers such as Ahmad Jarjour, Maya Medwar, Samiha, and Zenouba. The head isolations were inspired by Jamila’s second husband, a professional kathakali dancer. Jamila observed Tabora Najim, a Turkish dancer, performing what Jamila named the Turkish Drop.

Suhaila Contributes

In addition to Jamila’s diligent observations, Suhaila began adding her own in the 1970s. For example, she identified Singles on the Down by watching Sohair Zaki and Ahmad Jarjour. Some folkloric steps were inspired by Lala Hakim. Suhaila added others based on what she observed in weddings when she visited Cairo at the age of 14. Jamila had Suhaila document additions from Rita Alderucci (Rebaba) and Debbie Goldman, two of Jamila’s students who shared what they observed from dancers while abroad.

Isolations, Vibrations, and More

Before the 1970s, isolations as we know them today were relatively rare in belly dance. A dancer might perform one signature isolation. However, dancers almost never performed pops and locks as they do now.

In the 1970s, Jamila and Suhaila saw performances by Nagwa Fouad, who would vibrate her hips and accent the music with large ribcage locks. Soon after, they also saw Mona Said adding large body locks to the breaks in her music.

Suhaila was inspired not only by Mona and Nagwa, but also her training in jazz dance and the movements she learned from the poppers and lockers at Fisherman’s Wharf in San Francisco. Accordingly, Suhaila added these new movements to her own dance and the Jamila vocabulary in the late 1970s.

The Legacy of Bal Anat

Bal Anat was also the first belly dance company of its kind, presenting group dances in different ethnic and fantasy styles. When each “group” of dancers performed, the remaining dancers would continue to dance and play finger cymbals in a half-circle behind them.

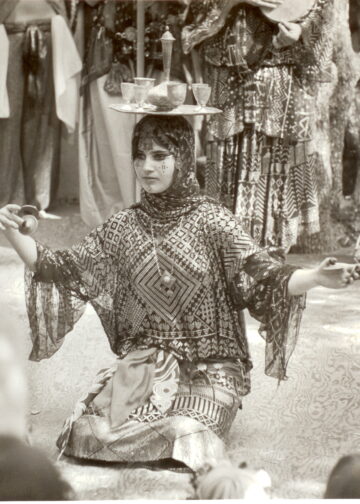

Upon creating Bal Anat in 1968, Jamila found inspiration in both fact and fantasy to create a tribal and folkloric presentation. According to her research, Jamila crafted dances.

For example, inspired by a painting by Orientalist artist Jean-Léon Gerôme, she created the sword dance. In like fashion, inspired by ancient statues of snake goddesses, she had her dancers perform with snakes and balance on water goblets.

Once people saw her presentation, Jamila’s approach and ideas spread like wildfire. Although introduced in the late 1960s, many were considered standard knowledge for American belly dancers within a decade.

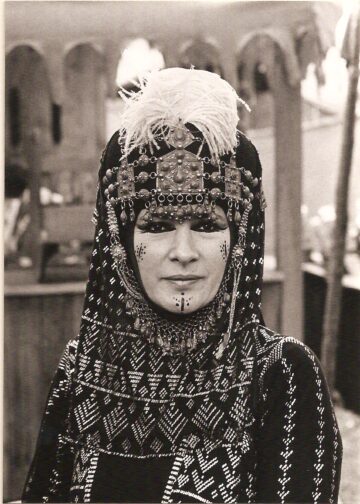

Costuming

Jamila also costumed the dancers of Bal Anat in heavy, earthy textiles and jewelry, such as Assuit cloth from Egypt. Today, many belly dancers continue to derive inspiration from Jamila’s aesthetic.

What is Real?

“I often said that Bal Anat was half real and half hokum. I regret this statement which is often quoted. My love of whimsy and alliteration distracted, and I feel I gave dancers open permission to do whatever they wanted to do, which was never my intention.

But what part was real? The dance was real. I studied and researched the steps which came from their cultures and countries. I gave attribution to the culture, both regular people and professional dancers.

Even the so-called fantasy dances have research and context. What was made up, or the hokum part, was the fairy tale of Lord Falmouth collecting these peoples and how they wound up being on stage together at the Renaissance Faire.”

Jamila Salimpour

From the Culture

Jamila’s goal was to focus responsibly on the unique qualities of each cultural dance and costume. She hoped to inspire the audience to learn more about the diverse and rich history, art, and culture of the many peoples from the Middle Eastern region. Jamila worked with and studied many professional dancers from across the Middle East who took their own traditional dances and created a version for stage (nightclubs).

By researching and consulting with these dancers, Jamila created the Bal Anat dances. Additionally, she created costumes for specific cultures using the stage versions of those steps and costumes developed by professional dancers from the same cultures.

Honor and Tradition

Many of Suhaila’s professional dancer colleagues had family tattoos that they displayed with great pride as part of their cultural identity. They expressed to Jamila that in the scenario she created for Bal Anat, where many groups come together, tattoos were an important element to give accuracy to the portrayal of each culture.

Tattoos were created to honor and represent long-standing generational traditions with the encouragement, guidance and permission of the professional dancers from those cultures. To this end, these “gifted” tattoos were generic to represent a specific culture but not a specific family. However, the Salimpour Family, specifically, was given more elaborate tattoos in addition to those from Suhaila’s Kurdish family.

Legacy

Over the years, Jamila continued to follow the guidelines of her professional dancer colleagues and furthered her research. Subsequently, Suhaila continued this legacy when Bal Anat was refreshed in 1998 under her direction. When evolving choreography and developing costuming, she followed the same guidelines for cultural respect and authenticity.

Sentiment

Although you practice the moves in repetition, Vocabulary students are encouraged to not think of the steps as drills. Each step family or step has an inherent sentiment and stylization. Most of the steps come from the dancers of the “Golden Age” of Egyptian Cinema (1930s-1940s) such as Tahia Carioca and Samia Gamal, who performed to classic compositions such as “Gamil Gamal” and “Tamr Henna”.

Internal and External

At their essence, steps have an internal or external focus, with a few having elements of both. As an example, some steps are focused externally as used in entrances and promenades. Others are focused internally as used in taqsims. This inward or outward focus affects the emotional intent and projection of the step.

“Music initiates everything. It’s not just the step sentiment.

Jamila believed, which she stated often, that if you aren’t dancing to Arabic music,

you aren’t belly dancing. While some may disagree with her,

belly dancing comes from a collective of cultures with rich musical heritage.

To be responsible to the culture and music is important.”

Suhaila Salimpour

Jamila was driven by the music and the rhythm. Undeniably, the music and rhythm gave context for sentiment and stylization. Accordingly, she looped songs for 30-40 minutes so she could be sure to maintain a consistent focus on sentiment and rhythm for a long period of time. She wanted students to have time to meld with the music and to find a personal connection to it.

The Multi-Part Dance Routine

When Jamila first began performing, dance routines performed with live musicians were typically no more than 10 minutes, and consisted of an entrance, taqsim, instrument solo, and a finale.

Club and restaurant owners made more money when the music was playing and dancers were dancing. Unsurprisingly, owners encouraged dancers to add variety and lengthen the shows. What had been 10 minute performances increased to 20 minutes, 30 minutes, and then an hour or more.

Dancers in the Northeast and on the West Coast began developing formulas, each region borrowing from the other. Over time, the American multi-part dance routine was established, having its heyday in the 1970s into the early 1980s.

The Role of Step Families

As Jamila compiled her steps into families, many of the families were directly applicable to sections of a performance. Each family had a different music selection requiring a different sentiment. Dancers performed three-, five- or seven-part dance routines. Generally, the number of set parts depended upon the venue, the dancer’s training level, and the band.

The seven-part version is outlined below. In comparison, the three-part version typically included an entrance, taqsim, and finale.

The Seven-Part Routine

- Opening: The dancer entered to a grand or upbeat composition, wrapped in a veil.

- Taqsim: During the taqsim, the dancer removed and danced with the veil.

- Middle: The band played a faster composition to which the dancer would demonstrate fast, precise movements.

- Taqsim: The dancer traditionally performed internally focused movements often while standing in place. In the 70s, dancers commonly performed floorwork or a sword routine.

- Song: A singer would perform a classic and/or popular song. During this piece, the dancer interacted more with the audience, and it was during this selection that any tips were given to the dancer.

- Drum Solo: The dancer and drummer(s) performed a duet.

- Finale: The music was usually dramatic and upbeat, often matching the opening music, and ended with a dramatic windup into a finale pose. Then the dancer performed her final promenade, acknowledging her band and audience before exiting.

Routines in the Middle East

During this same time in the Middle East, belly dance shows evolved slightly differently. Famous dancers were hired to do lengthy shows at high-end hotel nightclubs, for concerts, and on video. The most famous dancers had large orchestras and two-hour shows.

The folkloric dance choreographers, with their experience in creating long shows with different acts, were brought in to develop routines and performance flows.

Home Position (The Beginning)

- Feet are parallel in jazz 1st, weight over center of feet.

- Knees are bent but behind the toes.

- Lower abdominals are slightly contracted to maintain a flat back and protect the lower back.

- Chest is lifted.

- Diaphragm is open by contracting the latissimus dorsi muscles (lats).

- Shoulders are down.

- Arms are rounded above the head in 5th position.

Remember that your arms are connected to your upper back, and the upper back connects to your core.

No Place Like Home

“I enrolled Suhaila into multiple dance classes starting when she was two. Within just a few years, I could see the difference. Her posture and body line were strong, providing a better and safer frame for the movements. She looked like the newer dancers we were seeing out of the Middle East who were benefiting from ballet training.

Suhaila brought this posture into the Vocabulary, and she called in Home Position. Suhaila referenced Dorothy–from The Wizard of Oz (Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1939)–who repeats “There’s no place like home” as she clicks together the heels of her ruby red slippers.”

Jamila Salimpour

Home Position and Stylization

Jamila’s vocabulary is grounded and earthy. Unless specifically told otherwise, perform all movements from and within Home Position. For example, if a step requires an additional plié for stylization, that means you must bend your knees more than the default demi plié required to maintain Home Position.

Halftime versus Half the Timing

“Half the timing” or “Halve the timing” means to slow the timing by half. “Half the timing” is not necessarily the same as halftime; if students are working doubletime, then “half the timing” would be fulltime. The same concept applies for “double the timing”, “quarter the timing”, etc.

“Jamila never held back her students to do only the things that Jamila could do. If there was something important that she was unable to perform or break down, she would have me or an advanced student teach the step.”

Suhaila Salimpour

Body Bounce

Some Vocabulary steps have a subtle continuous bounce throughout all of part of the step. This bounce is not a simple layer that can just be added without evaluating its placement in context of a step and a step family.

Bounces are integral elements with relationships to other step elements. They might emphasize a weightedness or lifting quality, contribute to step sentiment, serve as the step heartbeat, or provide reverb or opposition response. The nature and quality of a bounce for each step is further explored and described in classes with Salimpour vocabulary training instructors.

Standard Body Bounce

The standard bounce alternates between Home Position (where you stand with bent knees) and a slight demi lower than Home. The bounce maintains a very small range, never moving higher than Home Position and not extending into a deep plie.

The bounce is notated in nomenclature as alternating Home and demi, downbeat Home or demi. It can also be written alternating Home and demi downbeat up (meaning Home, the top point of the bounce range) or down (meaning demi, the low point of the bounce range).

Standardization

“I strongly believe it is important to provide some standardization for this dance as in other classical dance forms including Indian dance. A knowledge and standard of technical proficiency should be set and evaluated by qualified instructors.

For those who prefer to attempt to preserve tradition, a vocabulary of traditional movements should be properly documented to serve as a basis for a standard of excellence within the dance form.”

Jamila Salimpour

The content from this post is excerpted from The New Danse Orientale, published by Suhaila International in 2013, 2nd edition March 2016. This book is a study guide for live classes and workshop instruction in the Jamila Salimpour Belly Dance format.

If you would like to make a citation for this article, we suggest the following format: Salimpour, J. and Salimpour, S. (2016). Foreword, Introduction, and Content. The New Danse Orientale. Published by Suhaila International in 2016, 2nd ed. Salimpour School. Retrieved -insert retrieval date-, from https://suhaila.com/danse-orientale/