Habibi: Vol.2, No. 5 (1975)

Morocco is one of the places where Middle Eastern dance enthusiasts have made pilgrimages to observe and, hopefully, study belly dancing. Many of them have come back in awe of the color, contrast, and ancient architecture of the old towns, but the dancing they saw was strange and, to them, a completely new experience. Once a year, in the month of June, the Folkloric Festival takes place in Marrakesh. For fifteen days tribes from all over Morocco come to participate and compete with each other…the prize being a medal which the happy winners take back to their village. The dancers are put up in houses for their stay, all expenses paid. Favorites are the all-male Gnaouan dancers who spin in controlled gymnastics while playing enormous double-decker finger cymbals [qarqabat]. Famous for their Guedra, the Blue Women from Goulimine dance on their knees and offer their breasts in gestures that predate Islam for many centuries. Most of the dances are in 6/8 tempo.

One of the most common comments I hear is, “I saw mostly boys and men dancing.” But men do not belly dance, do they? When their movements were described and demonstrated to me, it sounded and looked like belly dancing was not always, and still is not, exclusive to women. A quick study revealed the religious and social reasons for this tradition.

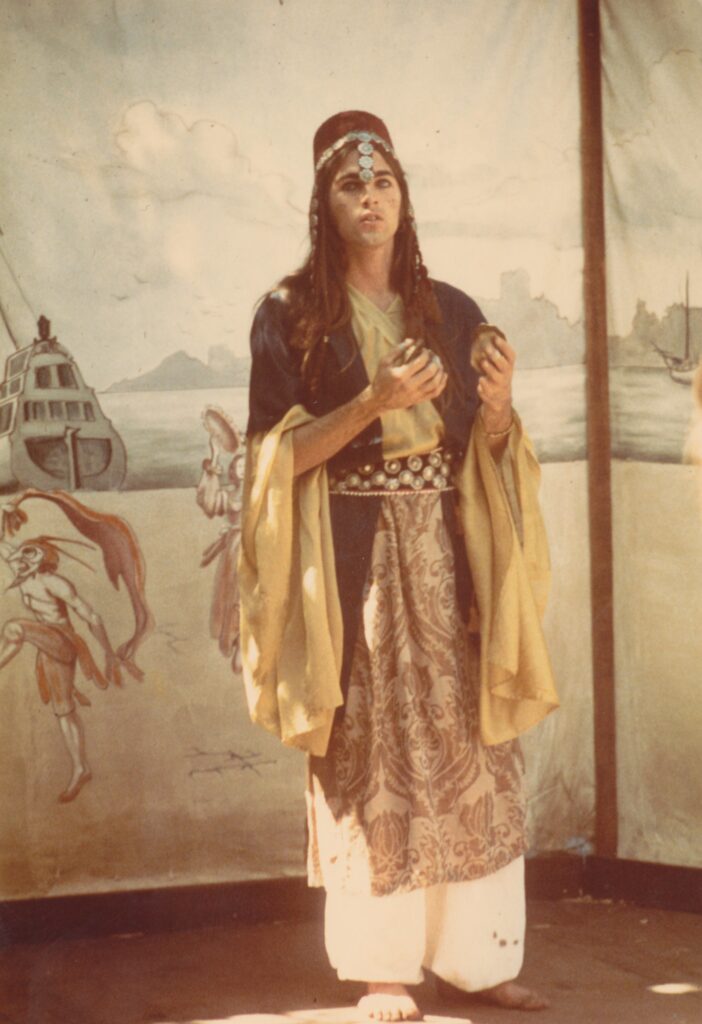

More recently Raphaela Lewis describes the dancing boys who were hired out as professional entertainers, and who were called “Chengi,” as wearing their hair in long ringlets and dressing like girls. Some of these dancing boys became extremely famous. When their beards would begin to grow they would stop dancing to train other boys and would accompany them as drummers. They were taught precise movements of the feet, arms, and head. To become accustomed to spinning, they were suspended in baskets from the ceiling which were spun around very fast. ³

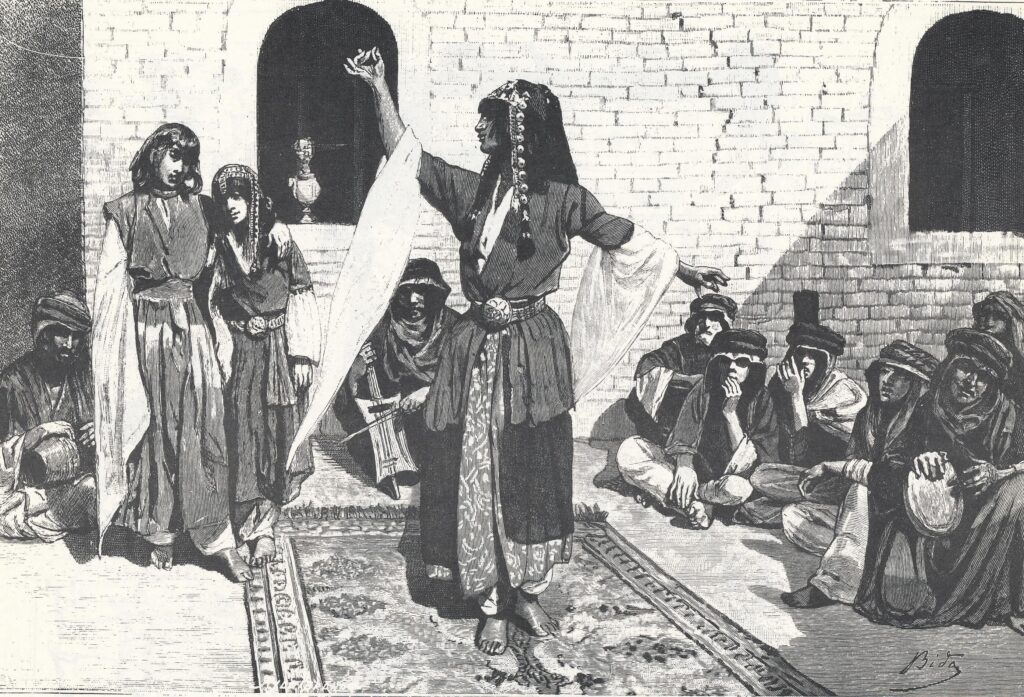

Articles on the Middle East appear quite frequently in National Geographic magazine. An article with photographs showing dancing boys entertaining guests describes their dress: “Khotan silk coats and long braids of hair from Kashgar. They performed several graceful dances which, since the artists were really young boys, seemed highly effeminate. ⁴ Further references indicate that when the danse du ventre was performed in certain areas, even though it was performed by both sexes, they were always dressed as women. ⁵ One of the most beautiful and naïve descriptions of a performance was written by Madame Jane Dieluafoy in her narrative of travel through western Persia in 1886.

Recently we saw a troupe of dancers, placed under the direction of an impresario of harsh appearance, advancing toward the tomb of Daniel, where they were to make a halt before reaching the tents of Sheikh Ali. The cries of musicians resound, the cylindri-conical drum rattles, the monochord violas grate ragingly. Young men, with long hair, put on female skirts, loosen the interminable sleeves of their chemise, and seizing the castanets of metal, improvise a lascivious dance, interspersed with the most unexpected pirouettes. The sleeves sweep the ground with their tapering ends, then spread the white wings over the head of the dancer, the skirts whirl, the hair flies over the face; behind the clouds of dust the boy disappears sufficiently to give the willing spectators the illusion of a danseuse. ⁶

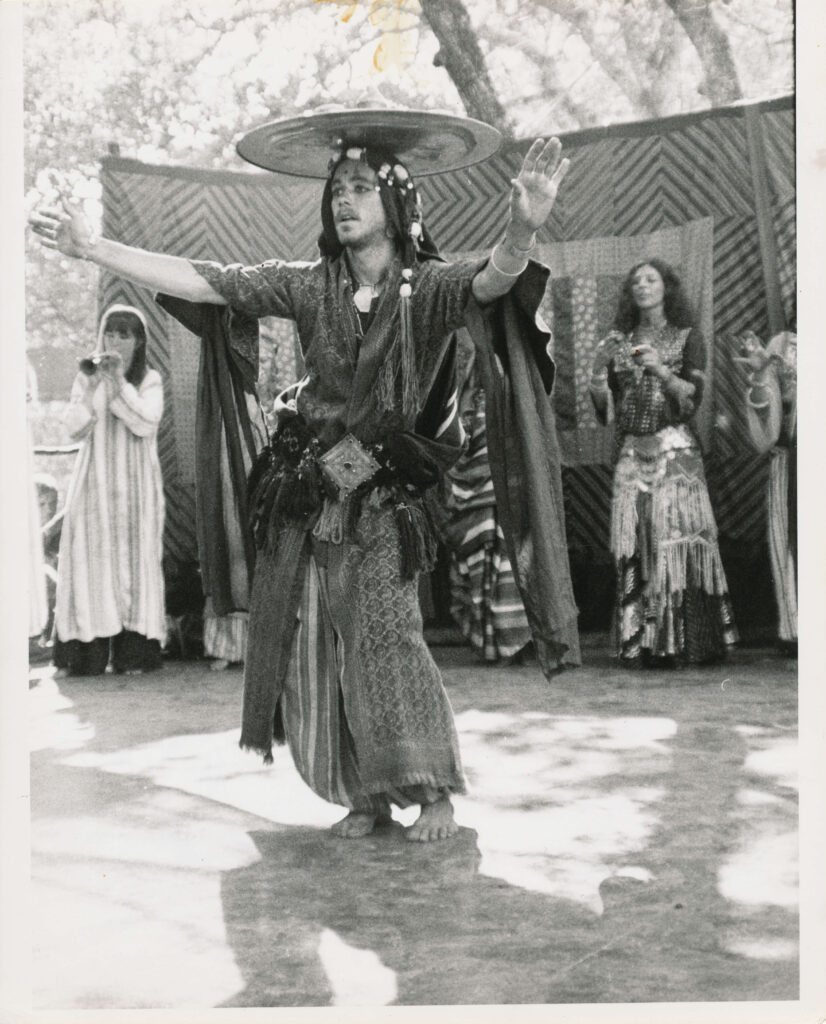

In a 1970 publication, the authors describe a dinner party given by a devout Muslim businessmen who, because of his religious persuasion, would only hire what is conventionally acceptable: male performers, musicians, and dancers; this is an accepted tradition, much the same as in Indian Kathakali, Japanese Noh plays, and Shakespeare. The article describes the bearded dancer veiled as a “female impersonator” who performed a sinuous acrobatic dance while balancing a tray of drinks on his head ¹. Why should he enter veiled as a female impersonator? An edict issued in Egypt in the year 1823, and still adhered to in tradition, accounts for the preference of the male dancer by many devout Muslims. In 1823, Edward William Lane wrote:

Many of the people of Cairo, persuading themselves to consider that there is nothing improper in the dancing of the Ghawazee (belly dancer) but the fact of its being performed by females, who ought not thus to expose themselves, employ men to dance in the same manner; but the number of these male performers, who are mostly young men, and who are called “Khawals” is very small. They are Muslims and natives of Egypt. As they personate women, their dances are exactly of the same description as those of the Ghawazee; and are, in like manner, accompanied by the sound of castanets; but as if to prevent their being thought to be really females, their dress is suited to their unnatural profession; being partly male and partly female, it consists of tight vest, a girdle, and a kind of petticoat. Their general appearance, however, is more feminine than masculine: they suffer the hair of the head to grow long, and generally braid it in the manner of the women; the hair on the face, when it begins to grow, they pluck out; and they imitate the women also in applying Kohl and Henna to their eyes and hands. In the streets, when not engaged in dancing, they often veil their faces; not from shame, but merely to affect the manners of women. They are often employed, in preference to the Ghawazee, to dance before a house, or its court, on the occasion of a marriage fete, or the birth of child or a circumcision; and frequently perform at public festivals. ²

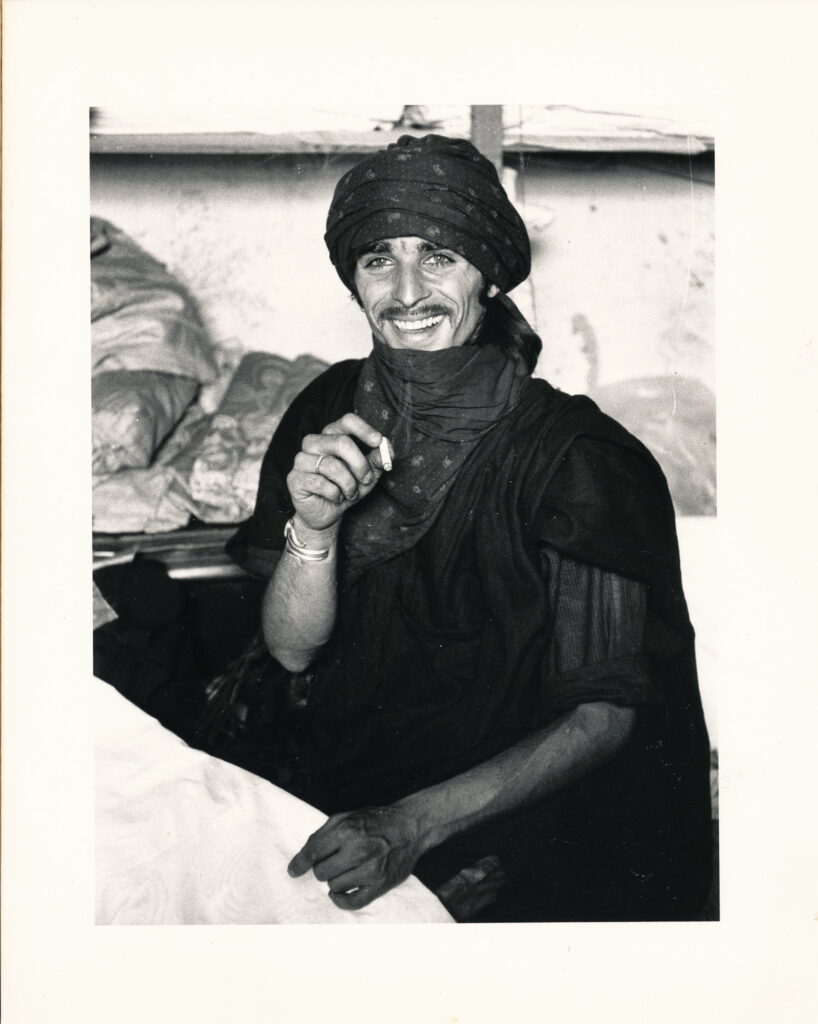

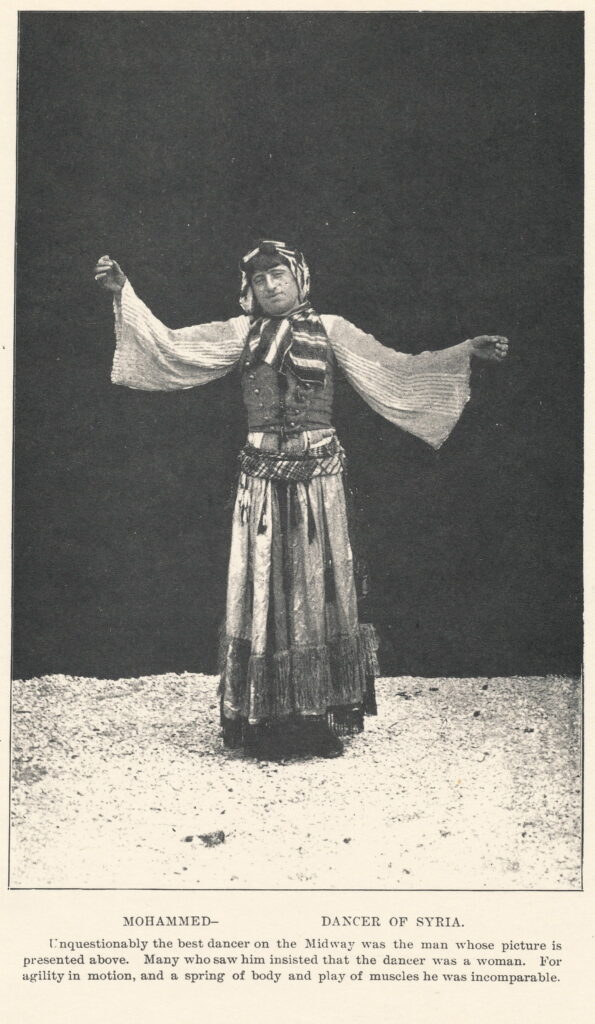

In reference to belly dancing of the past, we often hear about the notoriety created by the women at the “Street of Cairo” at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893. I was surprised and delighted to learn about Muhammed, a male dancer from Syria who was reportedly an excellent dancer who was often mistaken for a woman.

I think that males who danced did so as a means of making a living. One does not hear of male dancers in Egypt any longer, possibly because a large part of the Middle East has become sophisticated to the point where the dancing profession is not considered as base as in Lane’s day. The male dancers in Morocco and other parts of the Middle East are still a holdover from that day when women were forbidden to dance in public. From all accounts they are spectacular and I myself have seem a couple that brought the house down. A twentieth-century enigma? Not anymore!

Let’s bring on the dancing boys!

This article was published in Jamila’s Article Book: Selections of Jamila Salimpour’s Articles Published in Habibi Magazine, 1974-1988, published by Suhaila International in 2013. This Article Book excerpt is an edited version of what originally appeared in Habibi: Vol. 2, No. 5 (1975.)

¹ Michael Field and Frances Field, “An Exploration of the Exotic”, Foods of the World: A Quintet of Cuisines (New York: Time-Life Books, 1970).

² Edward William Lane, Manners and Customs of the Modern Egyptians (New York: E. P. Dutton, 1908).

³ Raphaela Lewis, Everyday Life in Ottoman Turkey (London: Batsford, 1971).

⁴ “Over the Roof of the World”, (National Geographic, 1932).

⁵ Princess Belgiojoso, Oriental Harems and Scenery (New York: Carleton, 1862).

Photo captions

Group of Gnaoui Performers, 5 March 2015, Photograph, Brahim Djelloul, Creative Commons SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:DANSE_GNAOUI_A_TIMMOUN_021.jpg

Arabian dancers, woodcut, 1888, Public Domain. In folder

Mohammed, Syrian Dancer, Pictorial works, World\’s Columbian Exposition (1893 : Chicago, Ill.) — Pictorial works, 1893, Buel, James W.; Smithsonian Libraries, Public Domain. In folder

Darius performing the tray dance as a member of Bal Anat, circa 1970s. Unknown Photographer. From the Jamila Salimpour Danse Orientale Archives. In folder

Jay Goodman. Unknown Photographer. From the Jamila Salimpour Danse Orientale Archives. In folder

Danseuse Arabe, 19th_century, Turkis KocekDancer, Public Domain. From the Jamila Salimpour Danse Orientale Archives. In folder

John Compton, dance member of Bal Anat, c1973, Photograph, Unknown Photographer. From the Jamila Salimpour Danse Orientale Archives. In folder