Habibi: Vol. 3, No. 12 (1977)

The oldest records of organized music are Sumerian and Egyptian. Sumerian texts written in 3,000 BC frequently speak of religious music used in the great temple at Lagash in which officials were responsible for choral singing and training of male and female musicians. A caste system was established within the guild which was attached to religious centers. The court orchestra of Elam, whose members played harps, double oboes, and drums, suggests a high standard of music education, skill, and knowledge.¹

When Egypt conquered southwest Asia in 1,000 BC the subjugated Kings sent tributes of dancing and singing girls with instruments. The Egyptians were attracted to the stimulating Asian music featuring lyres, lutes, and drums. Nearly all the ancient Egyptian instruments were replaced. Shrill oboes replaced the softer flutes, and more strings were added to the standing harp.

The geographer Strabo advised his readers to present Indian Rajahs with musical instruments and pretty singing girls from Alexandria, and a navigator of the first century relates in his diary how he imported musical girls from Phoenicia to India.

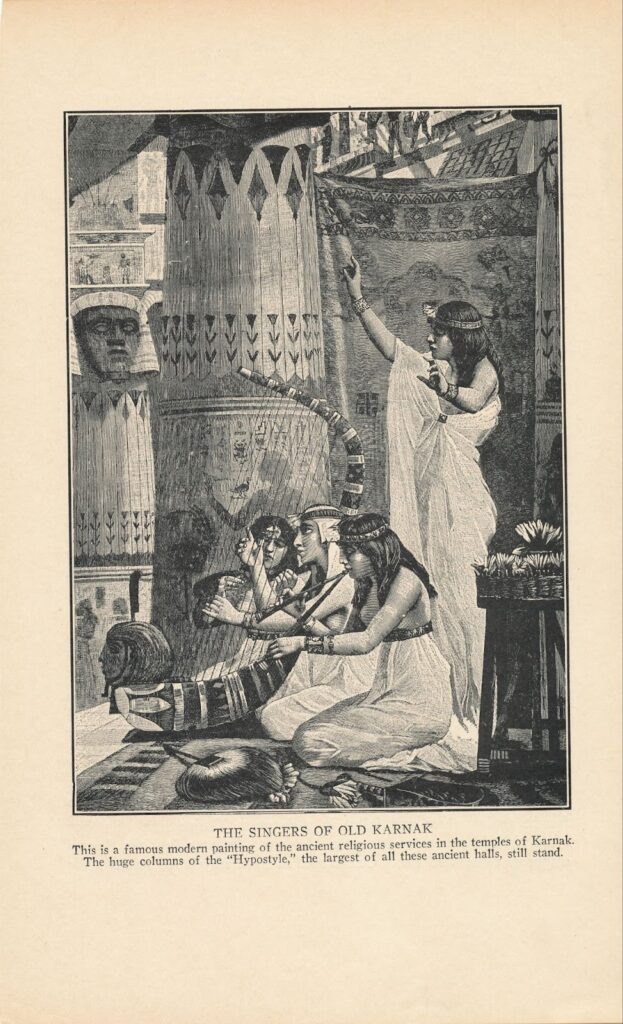

Undoubtedly, an active exchange between Egypt, Mesopotamia, and Greece spread the use of a variety of instruments. In most paintings depicting court life, we see the harp, lute, and double pipes (Aulos in Greek and Tibia in Latin).

In Egypt such instruments were the trademark of the Auletrides (female flute players) who also danced. ² Female flute players were a common accompaniment to an Athenian banquet. Though mythology connects the flute to the Greek God Pan and fabled King Midas, the flute was rarely seen in male hands in Greece.

Thebes appears to have been the native city of the earliest famous flute players. Soon thereafter, the Ionians and Phyrgians combined dancing with flute playing.

The lute came to Egypt (along with the lyre and small frame drum) and seems to have been played by women exclusively. The Egyptian lute, with the handle ending inside the body, has survived in Morocco as the girnbri, brought there when the Arabs conquered Morocco in the latter part of the seventh century. The long lute used in Arabian, Persian, Indian, and Turkish music keeps the ancient Babylonian form, having a small body and long neck. This is still a popular instrument in parts of the Balkans as well as the Orient. An instrument of this type, known as the Colascione, was played in Italy in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries³. Bonanni rightly says it had two or three strings, although the picture accompanying his text shows five⁴.

The frame drum is known to have been a woman’s instrument in the Near East for millennia. Balag-di, the ancient name for the frame drum, is mentioned in a Sumerian text documenting that a granddaughter of a king was appointed player of the balag-di in the Temple at Ur around 2,400 BC. From Asia, the frame drum, together with other instruments, traveled to Egypt. A rectangular version occurs under Queen Hatshepsut and a large rectangle is represented at Thebes in 1,500 BC. They are played by females, socially ranging from priestesses of Osiris to dancing girls. The present-day frame drum is usually round and is called both def and tar.

The tambourine was at different times called tabret, timbrels, and hand drum. The tambourine with jingles set into the frame appeared in Europe in the 13th century. Like so many medieval instruments, it came from the Near East during the crusades.⁵

The solitude of the Turkish harem gave ample time for ladies to indulge in music. Paintings of the seraglio depict women playing tambourines while singing and dancing, sometimes accompanied by a female playing a lute or an oud. One sumptuously dressed female musician was enticed away long enough to appear at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893 and boldly in the company of men, certainly a rarity in those days.

This article was published in Jamila’s Article Book: Selections of Jamila Salimpour’s Articles Published in Habibi Magazine, 1974-1988, published by Suhaila International in 2013. This Article Book excerpt is an edited version of what originally appeared in Habibi: Vol. 3, No. 12 (1977)

¹ Curt Sachs, The Rise of Music in the Ancient World (New York: W. W. Norton & Co, 1943).

² W. Sanger, History of Prostitution (New York: Eugenics Publishing Co, 1937).

³ Curt Sachs, The History of Musical Instruments (New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 1940).

⁴ Filippo Bonanni, The Showcase of Musical Instruments: All 152 Illustrations from the 1723 “Gabinetto Armoico” (New York: Dover Publications, 1964)

⁵ The New Oxford History of Music (London: Oxford University Press, 1957).

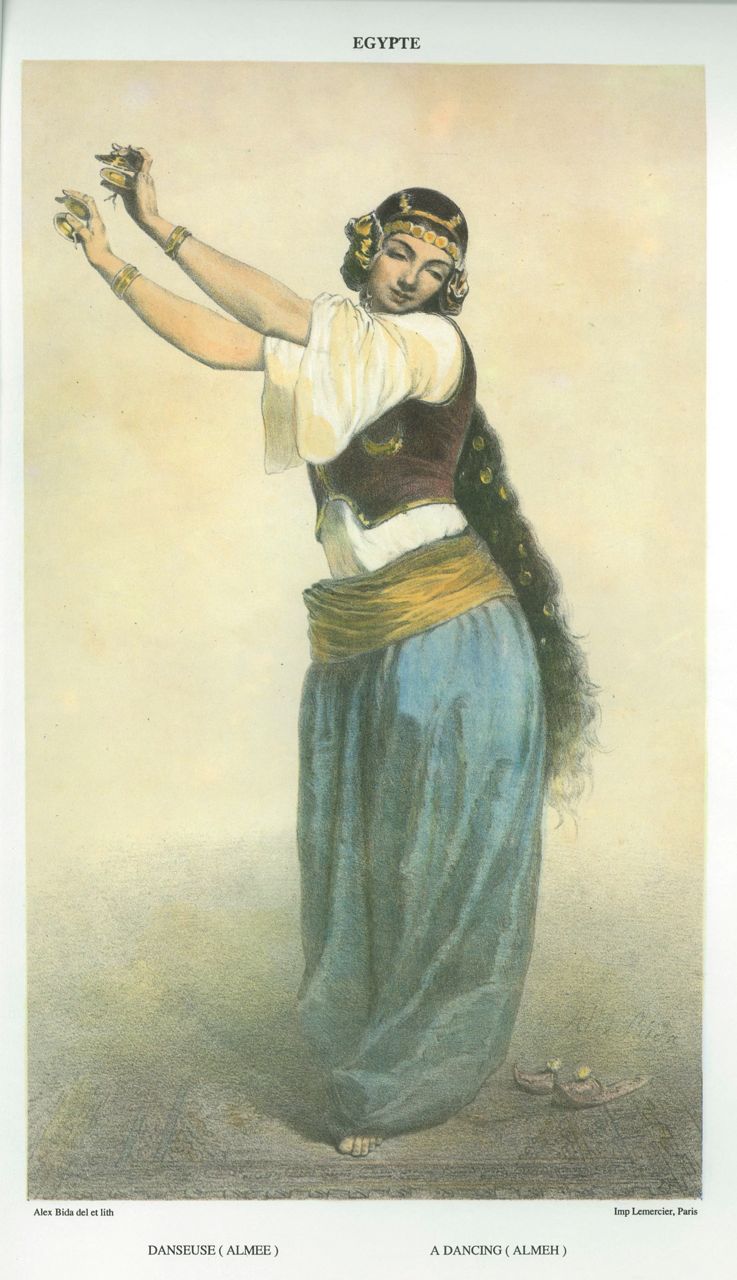

Photo Credits:

- Almeh or Belly dancing lady of Cairo, Egypt engraving on wood, The Human Race, Figuier, Louis, (1819-1894) Publication in 1872, Publisher: New York, Appleton, Public Domain, https://archive.org/details/humanrace00figugoog.

- Singers of Old Karnak, L\’Illustration Européenne, Engraving, Artist, Robert François Richard Brend\’amour, (1819-1894), Publication in 1872, Publisher: New York, Appleton.

- The Flute Player, Oil Painting On Canvas, Charles-Amable Lenoir (1860–1926), Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lenoir,_Charles-Amable_-_The_Flute_PlayerFXD.jpg

- Egyptian lute players. Fresco found in Thebes, from the tomb of Nebamun, a nobleman in the 18th Dynasty of Ancient Egypt (c. 1350 BC), Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Egyptian_lute_players_001.jpg

- Vintage postcard of Moroccan Musicians, Photo by Marcelin Flandrin, circa 1920, Public Domain.

- Vintage photograph of tambourine player, Unknown photographer, from Jamila’s personal scrapbook collection.

- Harem en Egypte, 1890, Livre XIXème siècle, Unknown artist, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Harem_en_Egypte.jpg