Habibi: Vol. 9, No. 12 (1987); Vol. 10, No. 1 (1987)

Naima Akef

Of all the dancers in the 40s, Naima Akef seemed to be the most versatile and prolific, appearing in films not only as an oriental dancer of traditional excellence, but also as an artist who understood the theatrical genre of the western world as well. When her career was seemingly cut short by her death during President Gamal Abdel Nasser’s regime ¹, gossip circulated in the Egyptian movie industry that it was most probably due to her being overworked by overzealous directors who insisted on numerous retakes of her dance routines. I wince every time I think of one routine she did in the movie Bread and Salt in which her tap dance ends in a one-hand cartwheel right into a split. I was told by the Egyptian movie people that came here [to San Francisco] with the Nagwa Fouad show that there were times when the director would have her do twenty-eight “takes” of one routine. Well, the Arab world was in shock at the news of her death. She was mortally stricken at the height of her career. We can only be thankful that we have any films of her which show her various talents which included singing and acting as well as dancing.

¹ Nasser became President of Egypt after leading a successful coup against King Farouk in 1952, and was president from 1956-1970.

I think Naima Akef is best known for her film Tamer Henna, in which she plays a dancing girl who falls in love with a boy who is “above” her class. This film captures the beauty of Egypt past, resplendent with many female entertainers dripping in a variety of assuit dresses and abundant traditional jewelry. The women wear crescent-shaped dowry necklaces and matching earrings, something that you rarely see in Egyptian movies today. What I really loved about Tamer Henna is that the movie was “truly Egyptian”, without a trace of Western, Indian, or South American influence. In fact, I don’t think there were any sets. It appears that all the scenes were outdoors in one picturesque setting after another, with the townspeople as extras. I was flattered when, in 1984, I received a letter from one of my students who was dancing in Egypt. One of her relaxing pastimes was watching old movies on Egyptian television. She wrote: “I saw Naima Akef on TV yesterday in an old movie. Jamila, I thought of you so much. She was so beautiful—her face, her body, (legs unbelievable) her assuit and those hips—they really were moving! I could see all your steps you teach in her dancing. I wish all your students could see these old movies to see what you’ve been talking about. To see what a woman she was.”

In Bread and Salt, Naima Akef portrays a show business baby who saves her town through her talent. In this movie she sings, tap dances, and does a reasonable facsimile of a Rhumba. Her baladi dance is extraordinary but far too short; most probably ended up on the censor’s cutting room floor. There is one thing I noticed about old time dancers which is missing in the dancers of today. Not only is the pelvic technique somewhat different, but all of those ladies could do knockout backbends…and that went for the ladies of the chorus too! The only other dancer I’ve seen that comes close to doing a similar backbend is Nadia Gamal who, in the film clips put out by TIV productions, does an indescribable backbend. Definitely something to revive and to strive for. Now, regarding the ladies of the chorus. Well, all those different shapes and sizes.

Certainly something for every taste from the almost skinny to the overly obese. In group dances I think they tried to have something of a choreography, but it doesn’t look like too many of these ladies knew their right foot from their left foot, but the results were charming.

Samia Gamal

Her figure was the Egyptian ideal; small waist, rounded hips, and a bountiful bosom. In the film Zenouba, Ms. Gamal improvises to “Zeina Zeina” as no other dancer has before or since. Her dancing had all the characteristics of an art form which was genuinely indigenous to her homeland, namely Egypt. Her style was her own, a soul dance which reflected her genetic origins. It wasn’t something that could be learned or even taught. That is why there hasn’t been another dancer who could move like Samia Gamal. Her style was one-of-a-kind which may have been imitated but never equaled. What was there about her walk, her stance?

There was that special pout, all with a certain humor, of course. Behind this extremely feminine exterior exuded an aura of strength. It surfaced especially when she danced. Her movements were secure and graceful. In a day when music was a pure reflection of the culture, Samia Gamal enhanced our preoccupation with the exotic. She was adored and idolized as the ideal woman of her day, King Farouk’s favorite dancer, whom she followed into exile. She was all the things that made a legend, and the Egyptians still feel the same way about her today. Samia Gamal made many movies with Farid al-Atrash, her dancing featured alongside his singing. Together they thrilled audiences in movie theaters who otherwise could not have afforded to see them in concert. How wonderful to see her in clothing styles which seem to be coming back. Draped, bias-cut dresses, clinging in all the right places, accessorized with wrapped turbans. In a film where she is depicted as a slave girl who dances her way into the heart of her master, Ms. Gamal models some very interestingly cut costumes.

The hero was the same actor who was featured in Yasmine. In this film, the slave-girl-dancer aids her master in securing revenge against the culprit who disrupted his marriage. What a surprise for Suhaila and myself when, after searching for and choreographing a dance in 1984-85, we saw Samia Gamal dancing to the same piece of music in this film. We had such different approaches and responses to the music, and for us it was very interesting to view and compare.

Tahia Carioca: The Eternal Essence of Egypt

She was the embodiment of the Eternal Egyptian Female. At a time when local dancers were hired for rural weddings and the stars of the big cities were patronized by a wealthy few, moving pictures brought to the masses the talents of such great performers as composer Mohammed Abdel Wahab, singer Oum Kalthoum, and dancer Tahia Carioca. She would also co-star with the young and popular singer Farid al-Atrash. Together they thrilled Arab audiences for years.

In her youth, Tahia Carioca had the perfect form and features of the idealized Egyptian woman. She had an inner beauty which exuded when she was in front of the cameras, exhibiting a natural reaction to the people with whom she worked. It was easy to watch her dance since she seemed to be totally involved when she performed. Indeed, she was so carried away that at times she would bite her lower lip for long segments of her dance.

As a foil for Farid al-Atrash, Tahia Carioca would react to his love songs, sometimes dressed in heavily sequined baladi dresses. The shape of her face was so perfect it needed little if any adornment. Many times her hair would be simply slicked back and her face encased in a peasant scarf with pom poms framing her forehead. Her hair was never much below her shoulders. It was wavy and most becoming when parted in the middle and combed back. Tahia and Farid complimented each other. That is why they would be cast together again and again. When audiences came to see their movies they were sure to see and hear the best of her dancing and his singing.

As Tahia Carioca matured she made several films which emphasized her acting talents and minimized her dancing abilities. Such was the case in Al Malemeh, a film in which she portrays a woman who remarries and becomes the victim of a jealous suitor. In this film she does a token dance in a long thobe, taking up a cane and later giving it to her husband who jokingly finishes the dance.

It was popular in the early 1940s to present Tahia Carioca as a dancer who adapted to western dance as well as excelled in oriental dance. Well, we almost have to consider what a favorite she was when we evaluate her attempt at other dance forms such as tap, foxtrot, waltz, and tango. Her tap was less than believable, but she looked cute as a button in her briefs which must have delighted much of her public and shocked more than a few. Although the routines looked simple, Ms. Carioca didn’t look comfortable throughout. It was with welcome relief when familiar oriental music would break out, and you knew Ms. Carioca would be in her element and in total control.

Where did they find the ladies of the chorus? And who dressed them? In a beautiful dance segment Farid al-Atrash sings “Ya Binti Beledi” to Tahia Carioca who is dressed in one of the heaviest assuit dresses I have ever seen. It has kimono-like solid metal sleeves which extended to her wrists. Another heavy assuit scarf is tied around her hips. She is wearing clunky shoes with anklets which she displays from time to time by picking up her dress to lift the hem; the anklets are the same style worn by Sohair Zaki. After watching this scene many times my attention has wandered from Tahia Carioca to the chorus line. The ladies of the chorus are also wearing anklets. They seem to be performing to a “loose” choreography, generally moving in the same direction. In one segment they are all filing past the camera, lifting their dresses to show their anklets as they shuffle along. They are in time to the music but all out of step with each other, one bobbing up as the other dips. Oh well! Not any of them were especially good dancers. I sometimes wonder how some of the ladies of the chorus were chosen.

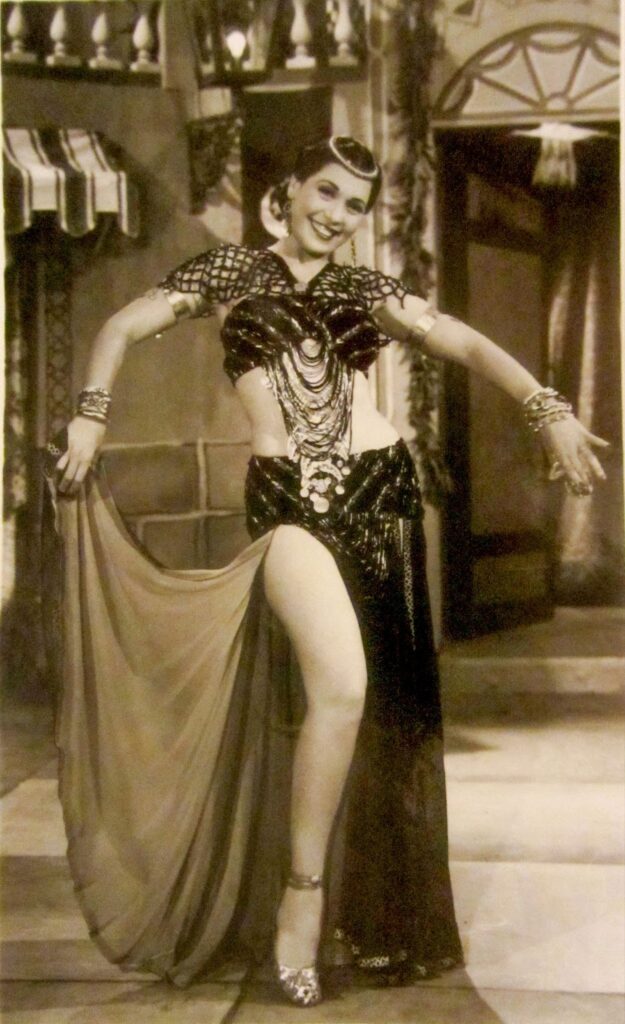

Back to Tahia Carioca! Although her countenance was demure, her costumes were often revealing. It was a time before the padded or formed bra, and many of her tops looked more like vests. All of her costumes were heavily encrusted with stones which sparkled so brightly they reflected like glowing prisms for the camera. What looked like thousands of rhinestones on her skirts posted the solution to the problem of uneven hems. The designs of her costumes were classical and flawless. One of the most repeated of her skirt designs was a slight A-line skirt slit in front all the way up to the girdle.

Imagine the fame and excitement of the high-class Egyptian nightclubs of the 1920s and the audience, mainly men, who were able to see the famed beauties performing for a privileged few. Then, with the advent of moving pictures, a new era of entertainment emerged when the masses could afford to attend and see all the famous artists again and again. I know with the Egyptian family which whom I lived, Tahia Carioca was a household name. She was a dancer who captured the heart of Egypt. Even today the name of Tahia Carioca translates into The Eternal Egyptian Female.

This article was published in Jamila’s Article Book: Selections of Jamila Salimpour’s Articles Published in Habibi Magazine, 1974-1988, published by Suhaila International in 2013. This Article Book excerpt is an edited version of what originally appeared in Habibi: Vol. 9, No. 12 (1987); Vol. 10, No. 1 (1987).