1876… or Business (and Belly Dancing) as Usual

Habibi: Vol. 2, No. 6 (1975)

The time is appropriate to share yet another discovery which will dispel the theory that belly dancing was introduced to the United States at the Chicago World’s Faire in 1893. Research comes slowly and from a variety of sources. The discovery of belly dancing as part of the Tunisian exhibition in America in the year 1876, was the result of a coincidence relating to my research.

In 1972 word got around that Theme Events was going to put on a Christmas [Charles] Dickens Fair. When I approached the entertainment committee they laughed and said “Jamila, what would belly dancers be doing at a Faire during the time of Charles Dickens?” I set out to prove that since trading between Europe and the Middle East had been going on for centuries, surely there must have been an ongoing exchange of music and dance.

My research soon led me to a book on the Crystal Palace Exhibition which took place in England in the year 1851 (exactly in Dickens’ time). Special music was composed and available for sale on music sheets whose covers showed a cross-section of the exhibitors and people at the 1851 Crystal Palace Exhibition (officially called The Great Exhibition). There were representatives of the Middle East, in a variety of dress, mingled with the Europeans in Victorian dress. In descriptions of the Faire activities one historian said, “As has always been the case at Bazaars, Faires, Expositions, and gatherings such as these, are the scenes of a vast variety of sideshows, spectacles, theatrical representations, juggling, and other amusements for the edification of the visitors, who in this way, combine business with pleasure.” Countries have traded not only goods but musicians, dancers, poets, and a variety of things both for propaganda and entertainment.

While I was in the throes of my research, a student of mine, Aida, visited me and brought me a print from an old book that showed a dancer accompanied by oriental musicians. It wasn’t exactly an exciting print, but as I inspected it more thoroughly I noticed that the text described the attendance of Queen Victoria at the Crystal Palace Exposition. It was that picture that convinced the Dickens Fair committee that belly dancers belonged at their event.

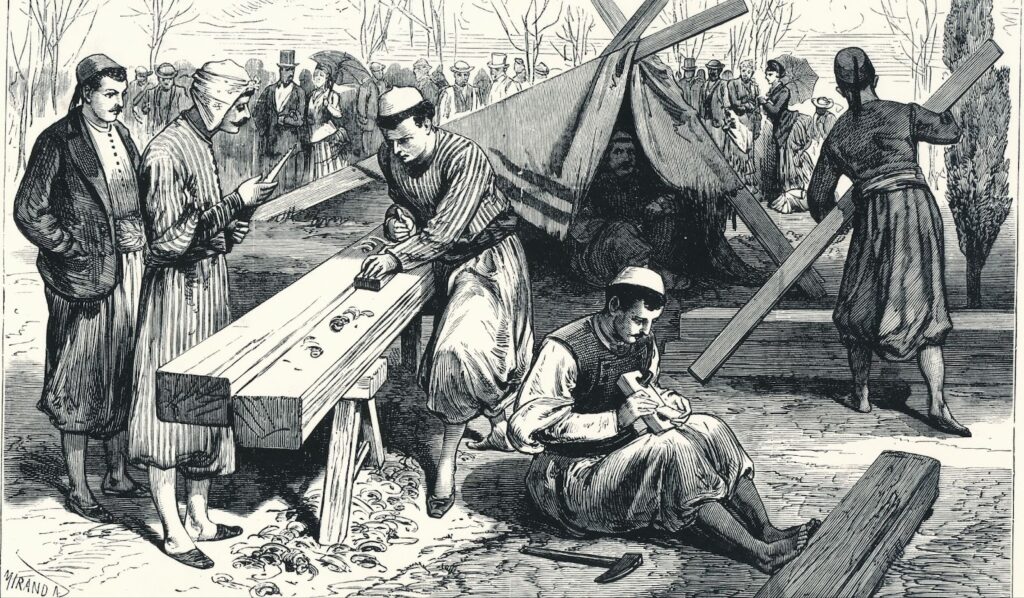

In 1871, President Ulysses S. Grant and the United States Congress approved funds to initiate an international exposition to be held in Philadelphia commemorating the centennial anniversary of the independence of the United States. Invitations were extended to the governments of other nations to be represented and to take part in the international exposition. Foreign nations sent their own workmen to build their individual exhibitions, some of which took up to five years to complete. Areas were designated to nations that participated. On May 10, 1876, the Centennial International Exhibition was officially opened.

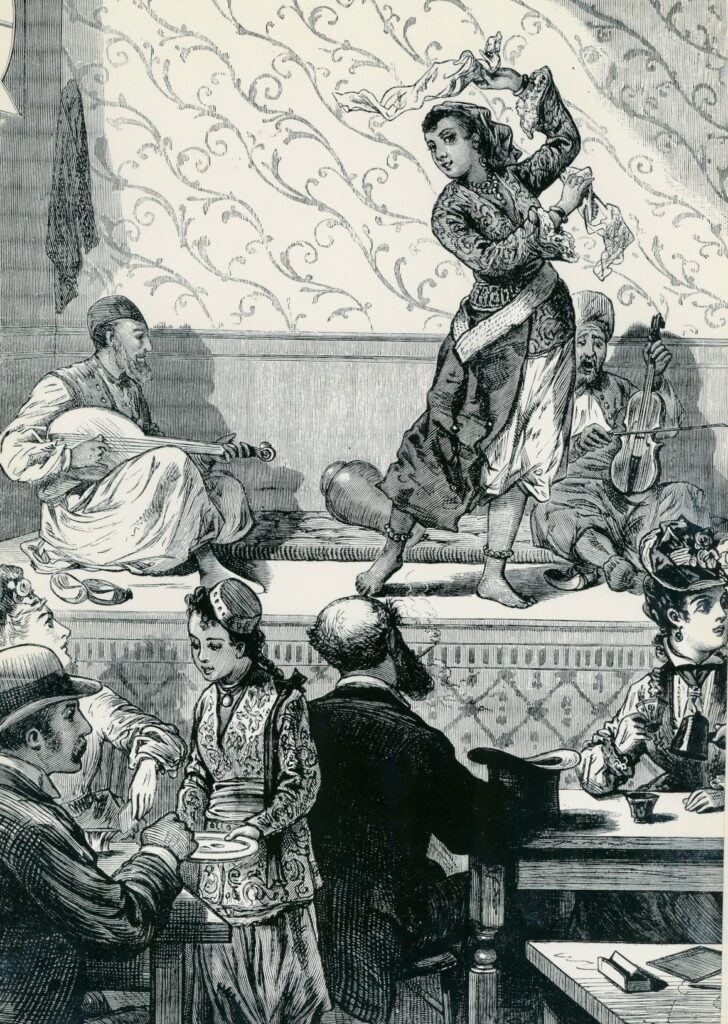

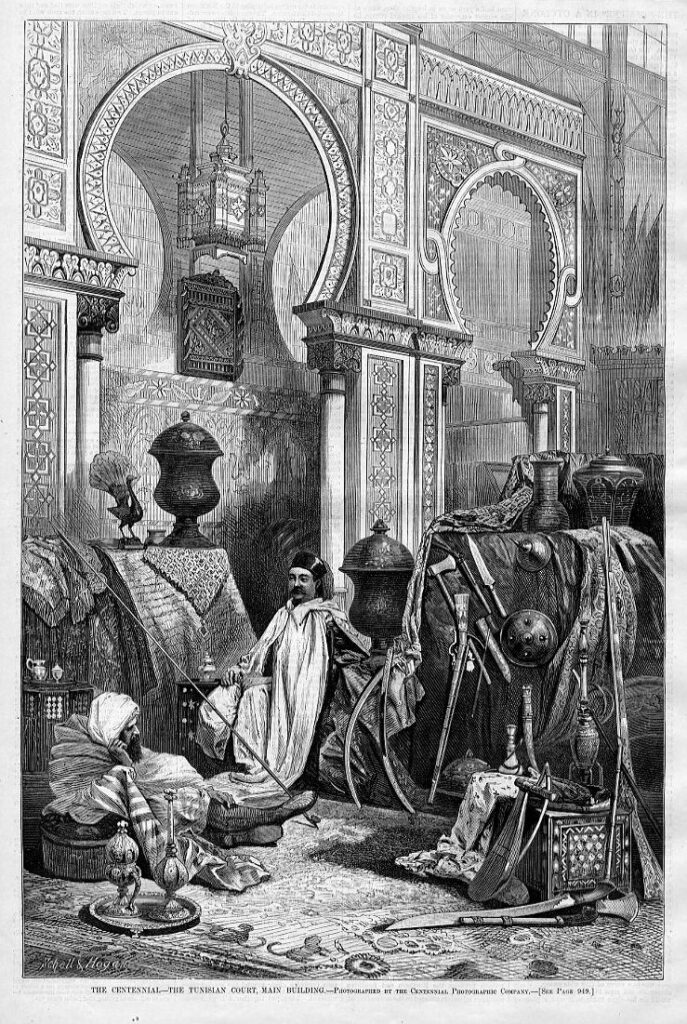

The Tunisian section included essences, flavoring extracts, pottery, carpets, rugs, jewelry, and national costumes contributed by his highness Mohammed el-Sadik Bey, Bey of Tunis. Musicians and dancers performed to their native melodies on a raised platform in the Tunisian Bazaar and Cafe. Coffee was served, and visitors were afforded the novelty of smoking Turkish tobacco through pipes two yards long. The Bey of Tunis also exhibited two Arabian tents, illustrating the domestic life and customs of the Arabian sheiks and Bedouins.

The Turkish display included masses of opium wrapped in leaves and beautiful Turkish carpets. The Turkish Bazaar and Cafe was presided over by Turks dressed in their native costumes: red fez cap, red tunic, yellow sash, with blue and brown silk trousers; they furnished visitors with pipes and coffee served in tiny cups. Small bazaars sold rich costumes, carpets, pipes, daggers, hilts, and many novel ornaments.

Egypt had an interesting display of the products and resources demonstrating the extraordinary talent of Egyptian craftsmen. A Turkish coffee set was exhibited, made in filigree work of 22-carat gold. Furniture inlaid with pearl and ivory, sables, saddles, silks, wine, opium, antiques, and hieroglyphic engravings taken from mummies were displayed. The exhibition was described as a dedication from “the oldest country in the world to the youngest country in the world”.

Sketches depict Tunisian workmen building a bazaar. A print depicts a scene from the Tunisian cafe: dancer and musicians on stage performing while young Tunisian children serve the Victorian attired customers exotic Turkish coffee. Women wait for their menfolk in an anteroom while the men try the nargila (water pipe) or the chibouk (long, wooden pipe).

When the exhibition closed in November 1876, nearly ten million people had attended. The gates grossed about $4 million. All sorts of centennial articles were offered at public auctions and eagerly purchased by the public. Egyptian, Turkish, and Tunisian furniture, jewelry, and bric-a-brac were sold to the highest bidder. That is undoubtedly how so many Middle Eastern souvenirs became heirlooms that somehow ended up in antique shops across America from estate sales.

I found no evidence of any anger or furor over the dancers at the centennial such as there was at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair. The Crystal Palace Exposition was considered a success.

This article was published in Jamila’s Article Book: Selections of Jamila Salimpour’s Articles Published in Habibi Magazine, 1974-1988, published by Suhaila International in 2013. This Article Book excerpt is an edited version of what originally appeared in Habibi: Vol. 2, No. 6 (1975).

Photo Credits:

- Scene in the Tunisian Cafe — The Scarf Dancer, Etching, American Centennial, Philadelphia, 1876, Vintage print from Jamila Salimpour’s Danse Orientale Archives. Public Domain. Image in folder

- Crystal Palace Tunis and China Exhibits, Dickinsons\’ Comprehensive Pictures of the Great Exhibition of 1851, Published in 1852, Smithsonian Libraries, Public Domain, https://archive.org/details/Dickinsonscompr1/page/n97/mode/2up

- The Centennial–The Tunisian Court, Main Building, World\’s Fair, Philadelphia, published in Harper\’s Weekly, November 1876, Public Domain. In article

- Furniture of the Turkish House, Etching, Historical Register of the Centennial Exposition, 1876, Frank Leslie, Published 1877, Smithsonian Libraries, Public Domain, https://archive.org/details/frankleslieshis00lesl/page/298/mode/2up

- Turkish Builders at The Crystal Palace Exposition, 1851, Etching, Vintage print from Jamila Salimpour’s Danse Orientale Archives, Public Domain. In article

- La Belle Tzigane, Turkish Gypsy Woman, Sébah & Joailler, 1890. Reprinted from Özendes, Sébah & Joailler, 162, Library of Congress, Public Domain, https://cas.umw.edu/dean/files/2011/08/Greene.metamorphosis-submission.pdf