At first glance, musical notation can seem very confusing. Indeed, it is a kind of written language that requires considerable study to master if one is to read piano music, orchestral scores, and other written music. However, learning to read basic melodic lines and simple rhythmic counts is not difficult.

In this section, we will discuss common rhythmic patterns and the most basic divisions of notes to represent them, as well as the appropriate terminology. You may notice that some of the musical terms used below are similar to dance terms, but may not necessarily mean the same thing. Here we are only talking about such terms in their musical context, with some comparisons to the timing terminology we use in the Salimpour School.

Western Music

In Western music (and by this we mean mainly musical styles that originated in Europe and non-indigenous North America), by far the most common types of rhythm are written in patterns of four or three beats, and to a lesser extent, in two or six beats (which are just variations on the first two). These are sometimes known as “duple” and “triple” rhythms.

In almost every style of Western music: pop, rock, classical, jazz, standards, these will be the most frequent rhythmic types you will hear. The reasons for this are complex and date back to the Middle Ages in Europe, where the foundations were laid for all music that came after in the West.

Music Notational Systems

The notational systems that developed allowed for the preservation of increasingly complex music in the long centuries before recordings. Other areas of the world (such as China) developed their own forms of notation, while many cultures continued to transmit music by oral tradition and memorization.

To say that something is “in” four beats simply means that the rhythmic pattern repeats every four beats: 1-2-3-4, 1-2-3-4, etc. The same is true for a song in three beats. A waltz is a classic example of a type of music in three: 1-2-3, 1-2-3, etc. Sometimes, the first beat in such patterns may be stressed slightly to indicate that the pattern is repeating, e.g., 1-2-3-4, 1-2-3-4, etc.

Musical Staff

In music notation on a staff (the five horizontal parallel lines used in musical notation), notes are used not only to indicate the melodic pitch of a given note, but also its rhythmic value. Together, these allow us to notate and preserve music so that it can be played again, as its composer intended. In this section, we will only be concerned with reading notes for their rhythmic values.

Notes and Rhythm

Rhythm is recorded by using different notes, some white, some black, some with stems, and some with flags on those stems. These all indicate the time value of that particular note. Note values are always divided in half as their duration becomes shorter. So, notes are classified as:

- Whole notes

- Half notes

- Quarter notes

- Eighth notes

- Sixteenth notes

- Thirty-second notes

And so on, though it is less usual for note values to go beyond 32 or 64, since they become so short in duration, they are increasingly difficult to play.

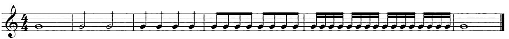

An Example with Four Beats

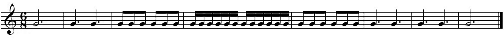

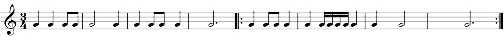

Let’s look at the first example, which is in a pattern of four beats. Again, do not be concerned with the tone value of the notes. We are only looking at rhythmic values:

The vertical lines are called bar lines, and they denote where the rhythmic pattern starts over. In this example, each division of four beats is called a measure. Thus, this example has six measures. They are all of equal value; each has four beats, but the number of notes in each varies.

The numbers 4/4 at the beginning indicate the “time signature.” This lets the musician know what the rhythmic pattern of the piece is going to be. 4/4 basically means “four quarter notes in each measure.” Generally, these numbers only appear at the beginning of a piece, unless it is changing to another time signature later, when the new time would need to be notated.

Measures 1-2

In measure 1 we have a whole note. This note is held for the entire duration of all four beats. An instrument, such as a violin or flute, would play the note for the whole measure. A whole note is often equivalent to a movement downbeat being in “quartertime” in Salimpour School notation.

In measure 2, we have two half notes. You can see how the whole note has been divided in half, and each has a stem. These notes are held for two beats each. A half note is often equivalent to a movement downbeat being in “halftime” in Salimpour School notation.

Measures 3-4

In measure 3, we have four quarter notes. Note that they are now black, and also have stems. There is one note for each beat in the measure. A quarter note is often equivalent to a movement downbeat being in “fulltime” in Salimpour School notation.

In measure 4, we subdivide again, into eighth notes. Now there are more notes than beats in the measure, and they are grouped together by a single bar across the top in groups of four (they can also be grouped as two or even appear as single, free-standing notes). There are eight notes, two for each beat. An eighth note is often equivalent to a movement downbeat being in “doubletime” in Salimpour School notation.

Measures 5-6

In measure 5, the notes have been divided in half again, and are now sixteenth notes. Sixteen notes are in the measure, with four on each beat. These would be played quickly. A sixteenth note is often equivalent to a movement downbeat being in “quadrupletime” in Salimpour School notation.

In measure 6, we return to the whole note again, for contrast.

Further Explanation

Note that the tempo remains the same throughout (i.e., it does not slow down or speed up). The only difference is the number of notes in each measure. There are twice as many notes in each measure as in the one before it.

These divisions are the standard form for writing rhythm in all music written in Western music notation. It is important to understand that though this notational system originated in Western Europe, it is now used universally around the world, as a standard means of notating and preserving melodies, though some types of music do not work as well with it as others.

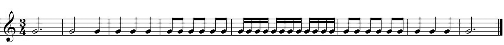

Example of Triple Time

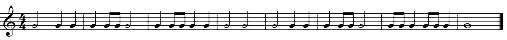

Let us now look at the next type of pattern, a triple time known as 3/4, which means “three quarter notes in each measure”:

This time, we see that there are eight measures (for no reason other than to provide contrast to the first example).

Measures 1-4

In measure 1, we have a dotted half note. A dot after a note has the effect of lengthening its duration by one-half. So, the half note here (two beats) is lengthened by an extra quarter note of time, to make three beats total. Again, this note is held for the entire duration of all three beats. An instrument would still play the note for the whole measure.

In measure 2, we have one half note and one quarter note. The measure, having only three beats, is not divided equally, but has one longer and one shorter note.

In measure 3, we have three quarter notes. Once again, there is one note for each beat in the measure.

In measure 4, we now have six eighth notes, two for each beat. This time you can see that they are grouped in pairs.

Measures 5-8

In measure 5, the notes have been divided again, and are now sixteenth notes. There are twelve notes in the measure, still with four on each beat.

In measure 6, we return to eighth notes.

Following, in measure 7, we return to quarter notes.

Then, in measure 8, we are back to the dotted half note.

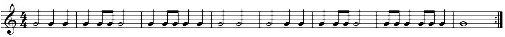

Second Form or Triple Meter

A second form of triple meter, 6/8, is also quite common, and sounds very similar to 3/4. The difference is that, as you might have guessed, it is a grouping of six eighth notes per measure, which changes the flow of the beat and the music, with the stress only coming every six beats instead of three. This type of rhythm is popular in Persian classical music, as well as Moroccan and African folk music.

In measure 1, you will see that we again have the dotted whole note, because, while it can represent three quarter notes, it also represents six eight notes in a measure. This is simply a way of letting the musician know to hold the note for the whole measure.

In measure 2, notice that there are two dotted quarter notes. Again, the dot lengthens the note value by one-half, so this stands for one quarter note and one eight note, or three beats in total. Combine with the second dotted quarter note, we get six beats total.

Next, in measure 3, we can see two groupings of three eighth notes each, so we have one note for each beat.

In measure 4, we have cut those notes in half to make sixteenth notes, giving us two groups of six sixteenth notes.

In measures 5-8, we reverse the process and make the note values bigger again.

More Examples

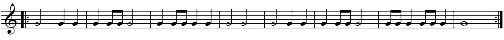

Of course, the way that music achieves its variety is through the combinations of note values in both the same and different measures; there are an infinite number of possible combinations. A piece in 4/4, for example, might look like this. Practice tapping out the notes to get a sense of the flow:

If you wanted to indicate that this eight-measure musical phrase repeats itself, without having to write it all out again, you would put the repeat symbol, a double-dotted bar line at the end. Here, this would mean to return to the beginning and repeat the section again:

If the musical phrase that you want to repeat is in the middle of a song, it is enclosed in dotted repeat bars on both sides, indicating that you repeat only the music that is in between them:

Generally, a musical section is only repeated once, whether with one or both dotted bars lines, unless otherwise indicated.

Let’s look at one more example, this one in 3/4 time, which uses the double repeat bar lines for the second half of the pattern:

Conclusion

With a bit of practice, reading this notation becomes easier, and will be very helpful in learning the patterns of the many Middle Eastern and Balkan rhythms listed later in this study guide. Quite a few of these rhythms are in 4/4 or 3/4 time signatures, but some are in unusual groupings, such as 5/8, 7/8, 9/8, 10/8, and 11/8, among many others (it tends to be more common to notate such rhythms with eighth notes as the basis). Understanding the basic Western duple and triple rhythmic notation will be invaluable in understanding these less familiar rhythms.

The content from this post is excerpted from Middle Eastern Music: History & Study Guide. A Salimpour School Learning Tool published by Suhaila International in 2018. This Music Book is an introduction to the music theory and main music exponents in the history of belly dance. The book is available to purchase as a hard copy here.

If you would like to make a citation for this article, we suggest the following format: Keyes, A. and Rayborn, T. (2018). Western Notation. Salimpour School. Retrieved insert retrieval date, from https://suhaila.com/western-notation