Habibi Vol. 4, No. 4 (1977)

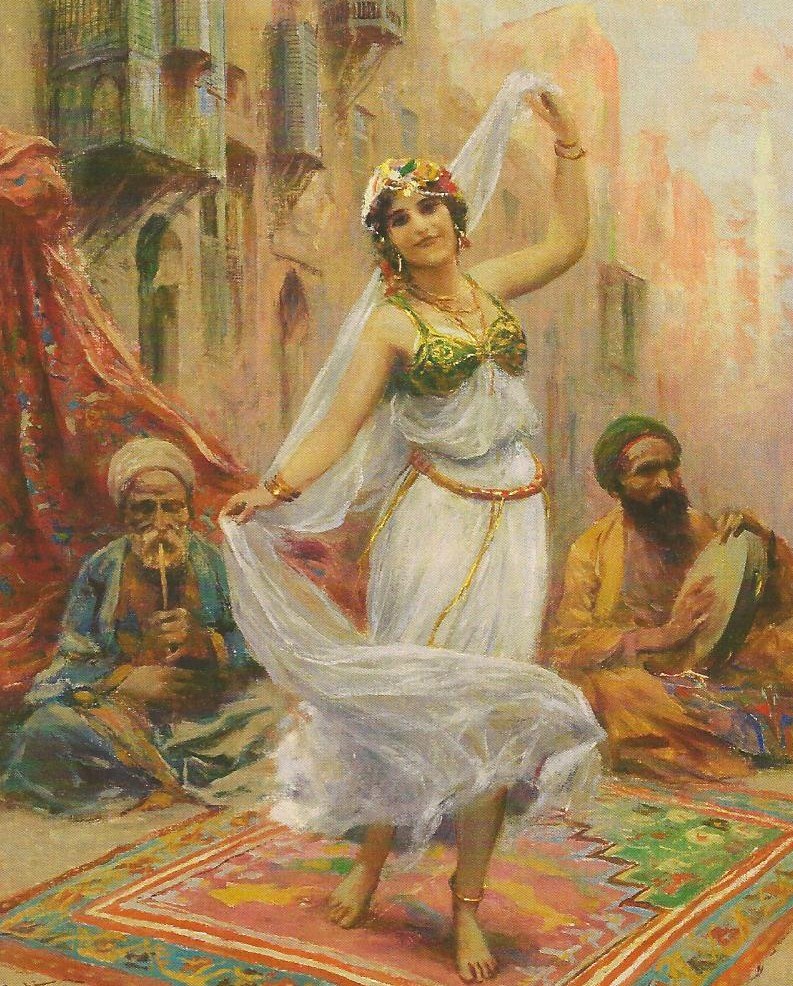

As is common today, the veil has become a dance prop used provocatively as a coy decoy and as a teasing means of bodily display. Middle Eastern tapestries and paintings depict old-time professional dancers fully covered but holding a rectangular piece of cloth behind them, conveying to us that the veil was an important part of the dance.

Although the veil does not seem to have been used in ancient Egyptian dances, it figured greatly in ancient Greek dances. When Greece became a power, she undoubtedly exported her dances along with her culture to her vast provinces which included the Egypt of Alexander the Great. Alexander brought his courtesans with him on his campaigns. Upon Alexander’s death, his most famous mistress, Thais, married his general Ptolemy and founded the Ptolemaic Dynasty whose most famous heiress was Cleopatra VII, Queen of Egypt.

When we try to connect the gestures in the paintings of ancient Egypt and relate them to the Middle Eastern dance of today we do not see a veil used in the dance. In Greece, however, the women wore veils, and we find many examples of veil dances depicted in the pottery, paintings, and sculptures from ancient times. The influence of Greek dance is seen in the frescoes of the Eleusinian Mysteries at Pompeii, where the ceremonies were concluded with a ritual in which the devotee symbolically puts on the “Veil of Purple” signifying a mortal attempt to communicate with the divine.

In the Greco-Roman world, decent women wore a covering over the head and a veiled face when going out of doors. For the most part, they were confined to the indoors, often not allowed to pass from one part of the house to the other without permission from the lord of the house. The area they lived in was called the women’s apartments which were generally in the uppermost part of the building and the most remote from the hall of entrance. Wilkinson writes:

In ancient Egypt women were not kept in the same secluded manner as those of ancient Greece, who were not even allowed to go out of doors without a veil; as in many Oriental countries at the present day. Newly married women were almost as strictly kept as virgins; and by the laws of Solon, no lady could go out at night without a lighted torch before her chariot, or leave home with more than three garments. They were guarded in the house and abroad by old men and eunuchs, and the secluded life they led was very similar to that imposed upon females among the modern Moslems. Although their faces were covered the veil was thin enough to be seen through. It was not, therefore, like the boorko [burka] of modern Egypt, which has two holes exposing the eyes, but rather like that of the Wahabees, which covers the whole head and face. ¹

The covering of the face, a gesture of modesty, was exploited by others who would have the populace believe they were pious maidens or matrons who could be pressured into submission. “While they were still young they covered their faces and breasts with transparent veils to allure clients”. ² This contradiction and corruption of gesture and meaning is noted in the forward of Maurice Emmanuel’s book: “The gesture of the veil is so beautiful that it has never fallen into disuse, dancers in all times recognizing its decorative value, even after the meaning has been lost. In the decadent period of Greek art, the veil gestures were used as they have been by certain modern dancers, more to emphasize nudity than to conceal it, thus perverting the original expression, which was one of modesty.” ³

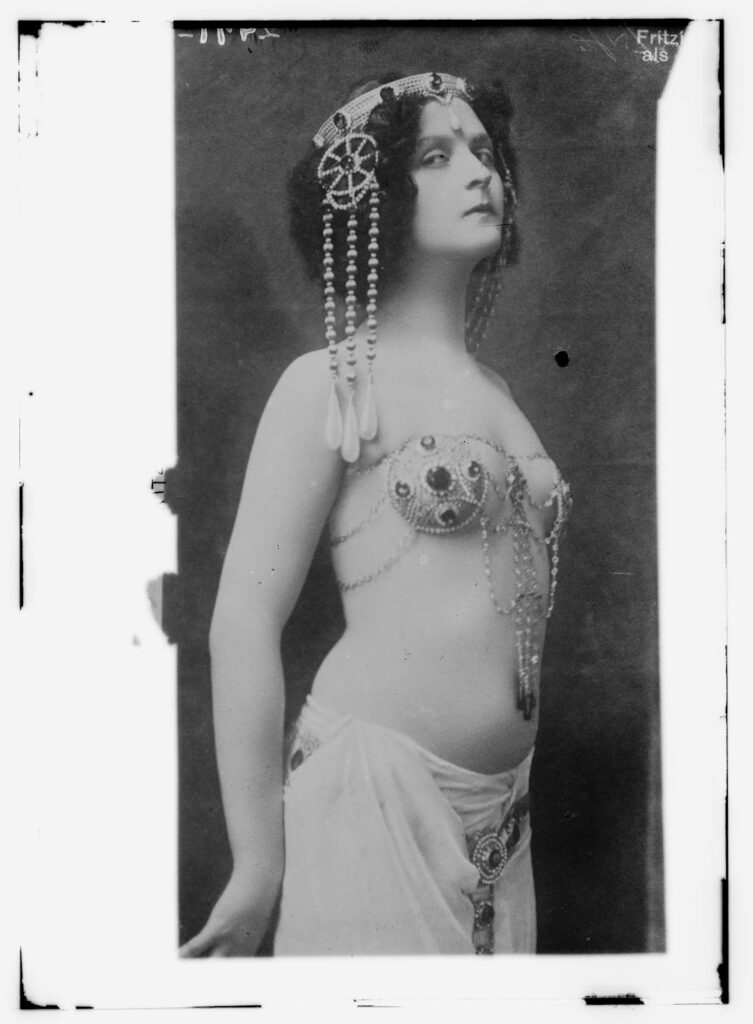

The most infamous veil dance was supposedly done by Salome for the King of Judea but, although it has come to be called “The Dance of the Seven Veils”, I could find no description of a veil dance in the Bible nor any detail as to how the Princess of Judea was costumed. Oscar Wilde was inspired to write a play about Salome endowing the princess with a menacing manner toward John the Baptist but, in fact, the choice of payment for her theatrical services was dictated to her by her mother Herodias, who had an inward grudge against the holy man for vehemently criticizing her lifestyle.

In one Bible passage, the veil is considered an accessory to vanity and the female reader is encouraged to discard it, along with her makeup and jewelry, (Isaiah 3:16-23), while another passage encourages women to wear it as a symbol of submission to the male. Rebekah saw Isaac, “so she took her veil and covered herself” (Genesis 24:65). In Corinthians 11:10, the inference is that when a woman puts on a covering, the covering represents that she is under the authority of her husband.

An old Bible circa 1864 does not use the spelling of today and refers to the covering as a vail, using an A instead of an E. Upon looking up that spelling in a dictionary of the same period, we find the meaning to be: Vail; to lower, in token of inferiority, reverence, submission or the like. Christian weddings still use the veil as a symbol of submission of the female to the male in marriage. In 1884 William Smith wrote a dictionary of the Bible in which he states:

With regard to the use of the veil, it is important to observe that it was by no means so general in ancient as in modern times. Much of the scrupulousness in respect of the use of veils dates from the promulgation (public declaration) of the Koran, which forbade women appearing unveiled except in the presence of their nearest relatives. In ancient times the veil was adopted only in exceptional cases, either as an article of ornamental dress (Cant. 4:1,3;6:7) or by betrothed maidens in the presence of their future husbands, especially at the time of their wedding, (Genesis 24:65) or lastly, by women of loose character for purposes of concealment (Genesis 38:14). Among the Jews of the New Testament age it appears to have been customary for the women to cover their heads (not necessarily their faces) when engaged in public worship.

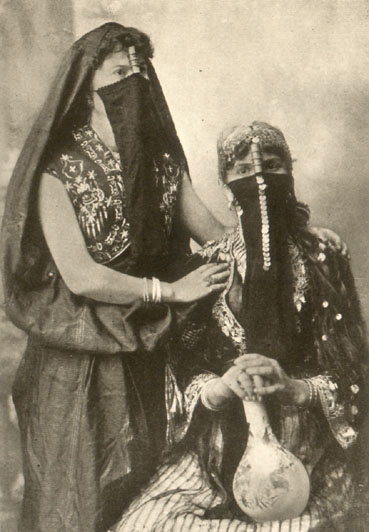

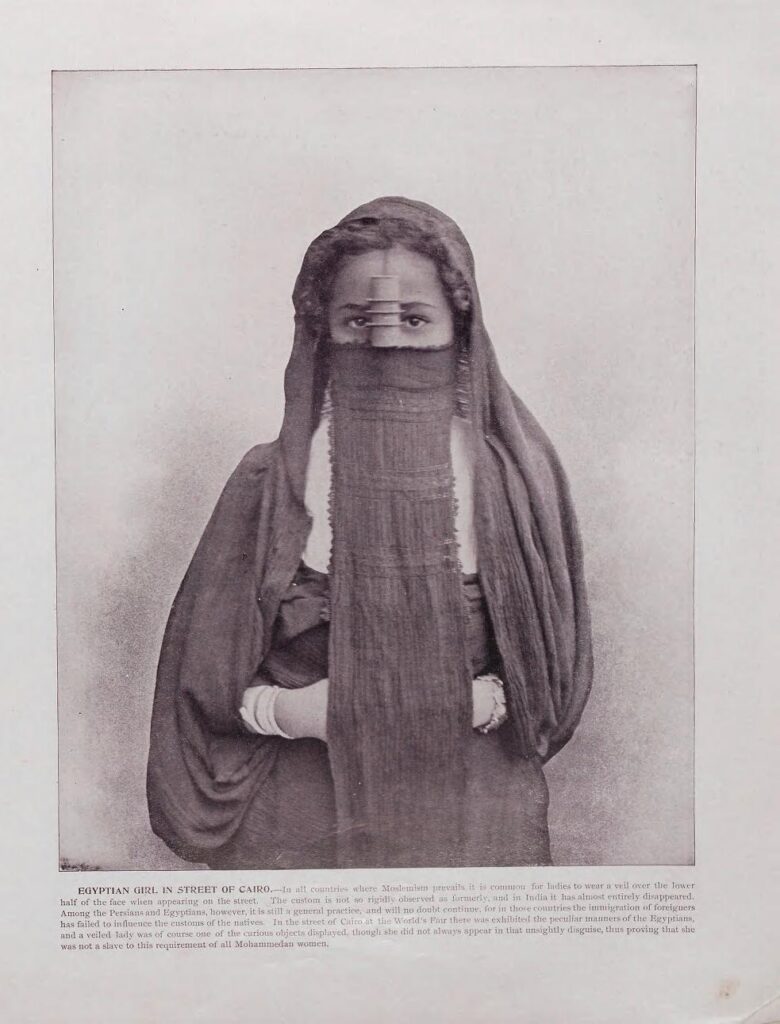

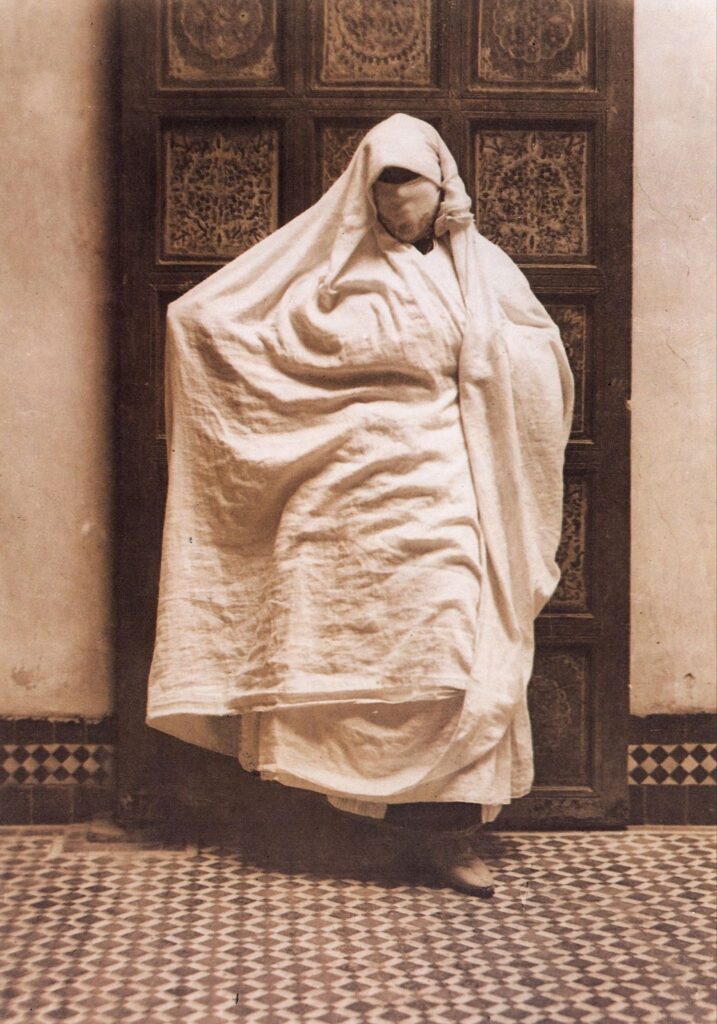

Today most people associate the veil with the religious practice of the Middle East, which devout Moslem women abide though now the veil is fast disappearing in the cities but it is still to be seen in the more strict rural areas where the habits of the people are slow to change. Strict Koranic laws forbid women to show their face in public and go so far as to require them to cover themselves entirely when venturing out for whatever reasons. They should not show their faces to anyone but their husbands and only in the seclusion of the home. The Koran reads (Sura 33;30), “Remain in your houses; and display not your finery, as did the pagans of old.” (Sura 33;55) “Say to thy wives and daughters and the believing women, that they draw the veils close to them”. ₄

In the early days of Christianity, Clement of Alexandria admonishes the female: “Let her be entirely covered, unless she happens to be at home. For that style of dress is grave, and protects from being gazed at. And she will never fall who puts before her face modesty and her shawl; nor will she invite another to fall into sin by uncovering her face. For this is the wish of the Word, since it is becoming to her to pray veiled.” ⁵

In describing the dress of the Egyptian women of the early 1800’s, Edward William Lane explains step by step what the women wear and in what stages they put on each item of clothing.

Next is put on the burko, or face veil, which is a long strip of white muslin, concealing the whole of the face except the eyes, and reaching nearly to the feet. The veil, in displaying the eyes, which are almost always beautiful; making them to appear still more so by concealing the other features, which are seldom of equal beauty; and often causing the stranger to imagine a defective face perfectly charming. The veil is of very remote antiquity but from the scriptures and paintings of the ancient Egyptians, it seems not to have been worn by females of that nation. In the present day, even the female servants generally draw a portion of the head-veil before the face in the presence of the men of the family who they serve, so as to leave only one eye visible. ⁶

A custom which still prevails in Persia is the wearing of the chador, a semi-circle which is draped over the head and pulled over the face. In Hajji Baba of Ispahan, James Morier translates: “Their veils were loosely thrown over their heads, which, upon my appearance, by a habit common to all our women, they draw tight over their faces, merely keeping one eye free.” ⁷ The Muslims brought their religion to North India along with the practice of Purdah, a word which comes from the Persian word “Parda,” which is a curtain worn by women to screen them from public observation; also the material for making such curtains. The yashmak, which was the Turkish rendition of the face-veil, was a kind of double veil worn by Muslim women when not in their private apartments. So, whether it was the burqa, yashmak, or the chador, it was used as a means to render the potentially tempting form of the female ineffectual; she became, when separated from life by the veil, anonymous to all but her husband.

The piece of fabric which makes up the veil dance has a history not only as a piece of clothing, but as an expression of modesty, submission, enticement, and abandon. For the performer it is a personal projection, and the spectator wonders which of these emotions is hidden behind the veil.

This article was published in Jamila’s Article Book: Selections of Jamila Salimpour’s Articles Published in Habibi Magazine, 1974-1988, published by Suhaila International in 2013. This Article Book excerpt is an edited version of what originally appeared in Habibi: Vol. 4, No. 4 (1977).

¹ John Gardner Wilkinson, Manners and Customs of the Ancient Egyptians Vol. 2 (London: John Murray, 1890), 60.

² Lujo Basserman, The Oldest Profession: A History of Prostitution (New York: Stein & Day, 1965), 14.

³ Maurice Emmanuel, The Antique Greek Dance after Sculptured and Painted Figures (New York: John Lane Company, 1916).

₄ William Smith, A Dictionary of the Bible (New York: John Winston, 1884).

⁵ A. Cleveland Coxe, ed, The Ante-Nicene Fathers Volume 2: Fathers of the Second Century (T. & T. Clark, 1896).

⁶ Edward William Lane, Manners and Customs of the Modern Egyptians (New York: E. P. Dutton, 1908), 46.

⁷ James Morier, Hajji Baba of Ispahan (New York: Random House, 1937), 286

Photo Credits:

- Oriental Dance, Pastels, Fabio Fabbi (1861-1910), Creative Commons (CC BY 2.0), https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Fabio_Fabbi_-_Oriental_Dance-3936351605.jpg

- Greek; Statuette of a veiled and masked dancer; Bronzes, 3rd–2nd century B.C., Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bronze_statuette_of_a_veiled_and_masked_dancer_MET_DP118070.jpg

- Egyptian Lady, Photograph, 1890-1923, Library of Congress, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Egypt-_Egyptian_lady_LCCN2001705649.jpg

- The Belly Dancer, Painting, Paul Joanovich, 1899, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Igracica_u_Skadru.jpg

- Belly dance performer Fritzi Schaffer as Salome, 1910, George Grantham Bain Collection (Library of Congress), Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Belly_dance_performer_Fritzi_Schaffer_as_Salome_LCCN2014691168.jpg

- Turkish Gentlewoman, vintage photographic print from the Jamila Salimpour Danse Orientale archives. No known copyright restrictions.

- No. 810 Deux Femmes Arabes, Photograph, Zangaki, circa 170-1890, Public Domain, https://omanisilver.com/contents/en-us/d450.html

- Egyptian Girl in Street of Cairo, World\’s Columbian Exposition (1893 : Chicago, Ill.) — Pictorial works, 1894, Buel, James W.; Smithsonian Libraries, Public Domain, https://archive.org/details/magiccity00fenw/page/n231/mode/2up

- Moroccan woman with haik, Photograph, 1915, Gaëtan Gatian de Clérambault, vintage photograph rom the Jamila Salimpour Danse Orientale archives. No known copyright restrictions.