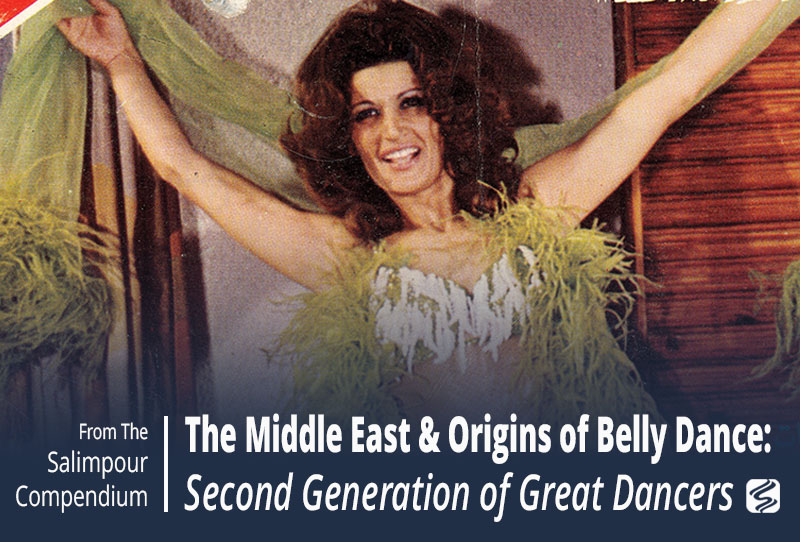

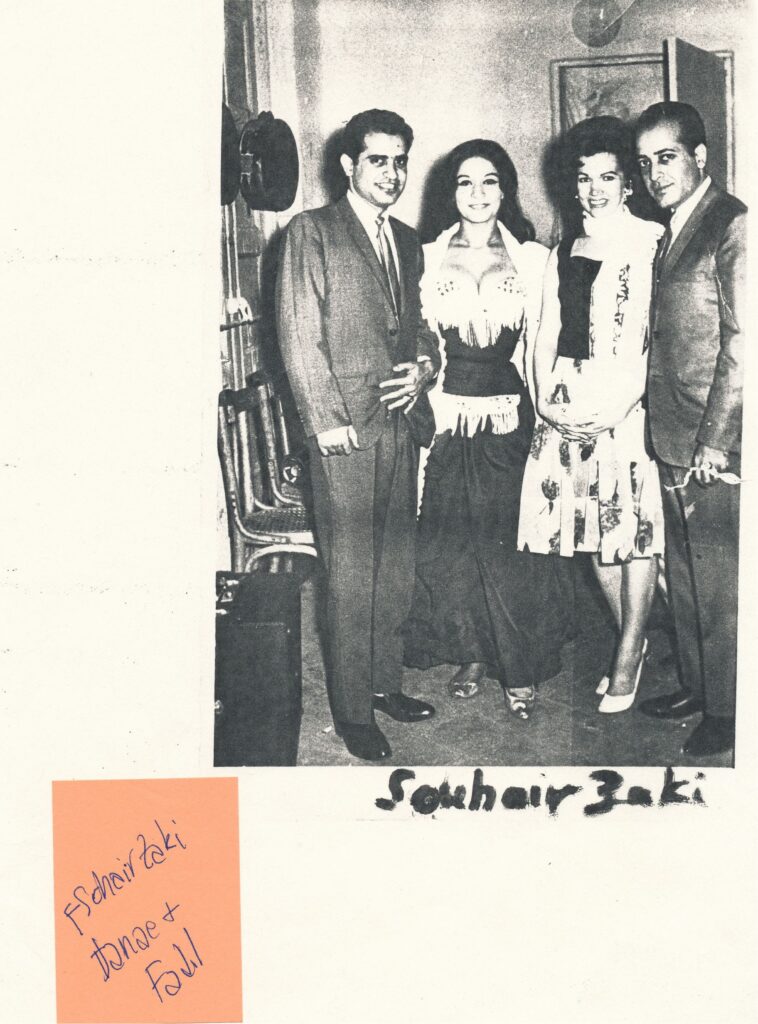

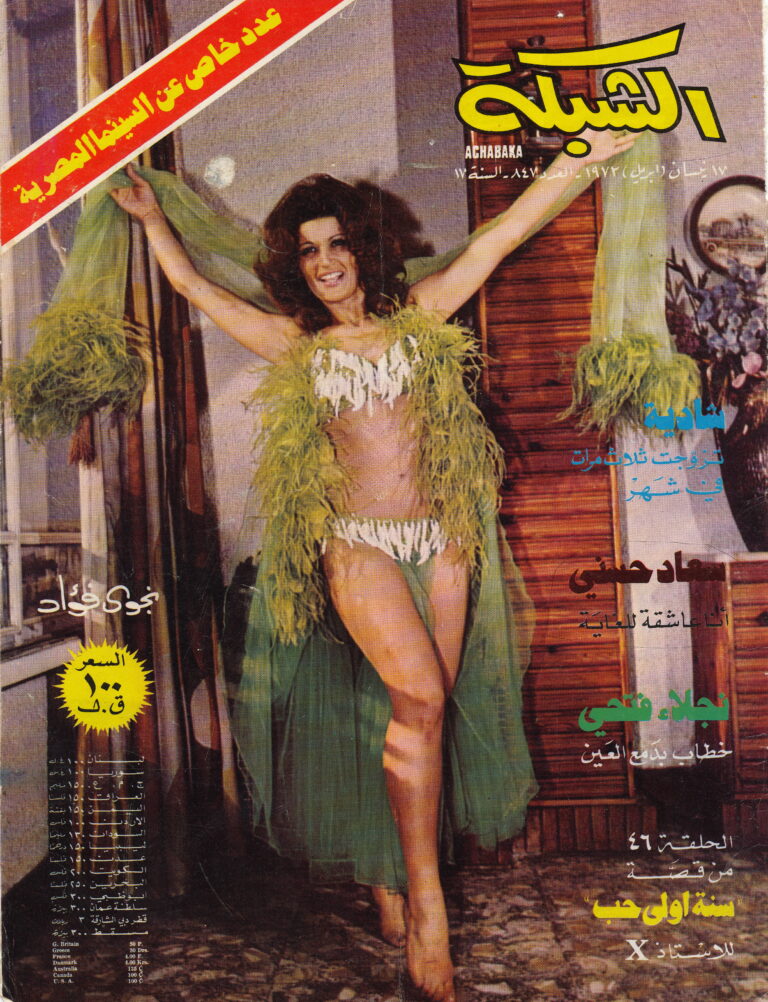

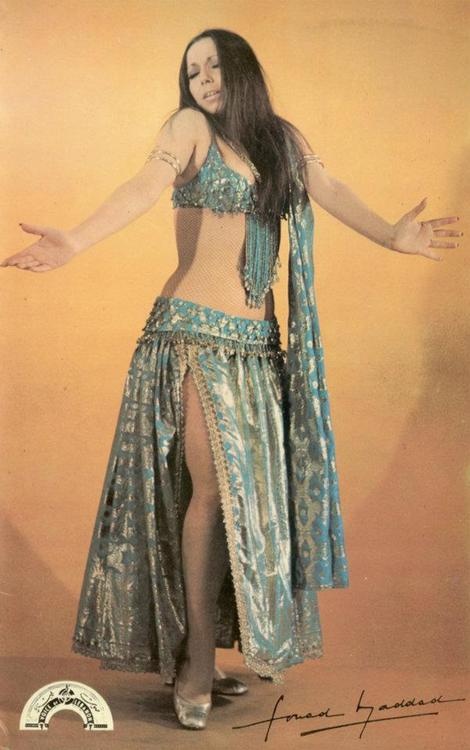

Sohair Zaki (1944 – )

Sohair Zaki was born in Mansoura, Egypt, in 1944 into a conservative family. Like many dancers before her, her family beat her and shamed her to discourage her from pursuing a career in dance. But after (most likely) sneaking out of the house one night to an Alexandria nightclub when she was 11 years old, a television producer discovered her and offered her a performance job. She began professionally at age 13, which her parents “accepted.” She told Shareen El Safy that appearing on television greatly helped her career and that she did not train specifically with any one dancer, instead borrowing elements from the famous dancers who had come before her such as Samia Gamal and Tahia Carioca.¹ In the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s, Sohair Zaki was praised and respected throughout the Middle East. The Shah of Iran, Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi, Tunisian President Habib Bourguiba, and Gamal Abdel Nasser all awarded her medals and accolades, and Egyptian President Anwar Sadat called her “the Umm Kulthum of dance.” She even performed at the weddings of each of the daughters of both Presidents Nasser and Sadat.² Respected American dancer Shareen El Safy calls her a “dancer’s dancer,” a dearly loved and respected Oriental dancer in the Middle East.³

Sohair Zaki was an innovator in that she was the first dancer to perform on television to music originally sung by Umm Kulthum; she first danced to a version of “Enta Omri” (“You Are My Life”) at an upper-class party in Zamalek (a neighborhood in Cairo). After her performance, she says, Umm Kulthum herself congratulated her and her band on their interpretation of the song.⁴ Now, of course, every star dancer in Egypt (and belly dancers around the world) performs to Umm Kulthum’s songs. Also, unlike her contemporaries, particularly Nagwa Fouad, she performed her shows with few costume changes and few or no props. She also preferred smaller musical ensembles, no more than a dozen well-selected musicians,⁵ although some sources claim she had as many as thirty. Her ear for music was impeccable; she could hear when one musician in her orchestra played a wrong note, and after the show would politely tell him exactly where he had made the mistake.⁶ Australian journalist Geraldine Brooks commented that after seeing Sohair Zaki dance, “Arabic music made sense to me. I could see it.”⁷ She always performed solo, without backup dancers; her costumes were simple and elegant.⁸ Her signature move was what we now know as “Hips on the Down,” (as named by Jamila Salimpour in her original format manual, La Danse Orientale) or even simply, “Sohair Zaki Hips.”

In the 1990s, after the Persian Gulf War, she retired, as the economy throughout the Middle East suffered, and many nightclubs could not afford to remain open; others felt pressure from a rising tide of social conservatism. She also disliked the changing costuming of the 1980s, when dancers began wearing form-fitting stretch fabrics instead of voluminous chiffon circle skirts. She came out of retirement; however, in 2001 to become a regular instructor at Raqia Hassan’s Ahlan Wa Sahlan festival in Egypt; her first workshop had over two hundred participants. She also cites depression as a reason for returning to dance, even though she does not plan to return to the stage.⁹

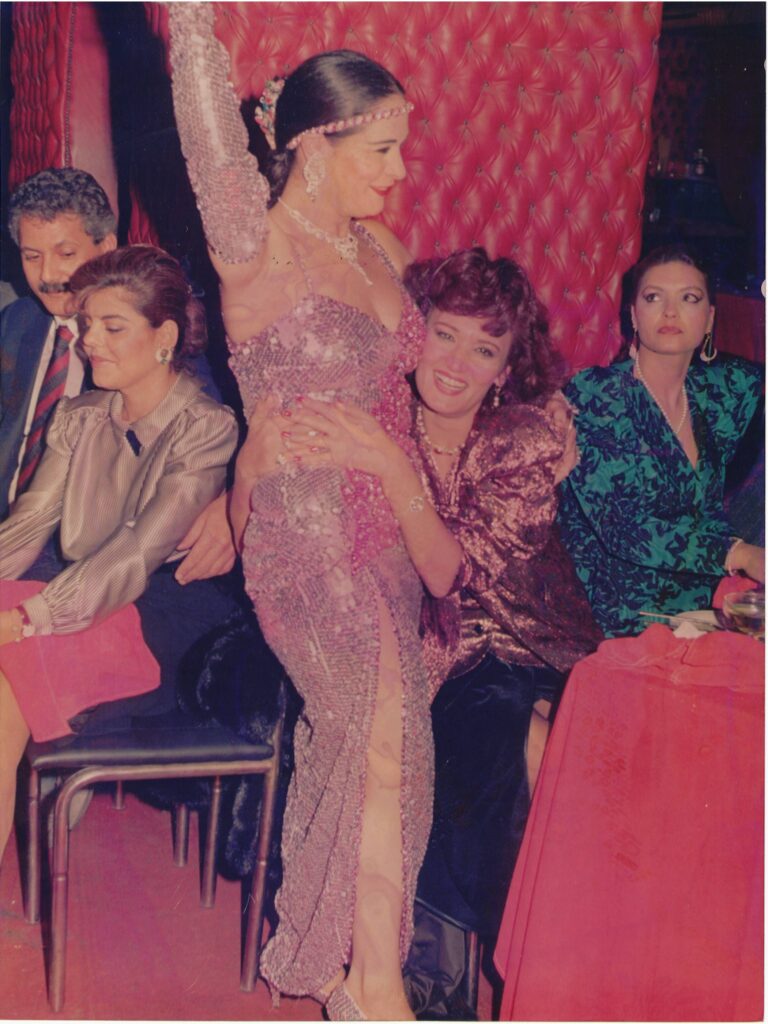

Nagwa Fouad (1943 – )

Nagwa Fouad was born in Alexandria, and when she was a baby, her family moved to Nablus, in what was then Palestine. After Zionist attacks on Nablus, and after the creation of Israel in 1948, Nagwa and her family fled back to Egypt. In the 1950s, when Nagwa was 14 years old, she obtained a job as a telephone receptionist in the office of one of Egypt’s top talent agents. After seeing her dance, the agent persuaded her to rent a belly dance costume and perform.

Her marriage to musician and conductor Ahmed Fouad Hassan helped her rise to fame; through his connections in the arts, Nagwa was able to study with Russian dance instructors (which contributed to Nagwa’s style) and secure roles in numerous films. Marjorie Franken says that she “brought strength and energy to her roles as the prostitute who dances to seduce the husband of another woman.”¹⁰ By the mid-1970s, Nagwa had become the top belly dancer in the Arab world and beyond. American Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, specifically asked to see her perform, as did United States President Jimmy Carter.

Nagwa Fouad met singer Abdel Halim Hafez on the set of Shari’ al-Hubb (Street of Love, 1958), and she and her company of twelve dancers starred as the opening act for his performances. In an interview with Grace Pagano, Fouad said that what makes her a star is that she knew “everything there is to know about my music,” because her first husband was a composer and taught her how to read music, “listen to it, and how to master it in the dance.” She performed to forty-piece bands and insisted that every musician attend rehearsals.¹¹

In 1976, Mohammed Abdel Wahab composed “Qamar Arbat‘asher” (“The 14th Full Moon”) especially for her. Because of the composition’s complexity and nuance, Nagwa developed a choreography to reflect the changes and moods within it, while building upon the dance traditions that dancers like Samia Gamal and Tahia Carioca created before her. This innovation influenced most belly dancers who followed, and choreography began to supplant improvisation in her performances. Like many belly dancers before her, Nagwa’s dedication to the dance brought her marriage troubles, and throughout her career, Nagwa Fouad fought to gain respect for belly dance as an art. Her career has spanned more than five decades, and in recent years, she has organized and produced large dance shows at five-star hotels, backed by troupes of dancers and other entertainers.¹²

Nadia Gamal (1937 – 1990)

Born Maria Carydias, to a Greek father and Italian mother in Alexandria, Egypt, Nadia Gamal trained in various dance forms in addition to belly dance—ballet, jazz, modern, tap, and acrobatics—as well as playing the piano when she was a child;¹³ she made her public performance debut when she was 14, performing belly dance in her mother’s show in Lebanon. Nadia Gamal first began performing European folk dances as part of her mother’s cabaret act at Badia Masabni’s Casino Opera, being one of the last Oriental dancers in the Middle East to have. In 1968, Gamal became the first Oriental dancer to perform at the Baalbeck International Festival, the oldest and best-known cultural event in the Middle East and the eastern Mediterranean. She toured extensively, performing in Europe, East Asia, as well as in North, South, and Central America; she was able to read, write, and speak in seven languages.¹⁴

Nadia Gamal was known for her extensive use of floorwork, and many dancers credit her with creating the modern style of Lebanese style belly dance. She is also one of the first belly dancers to incorporate a theatricalized zār¹⁵ into her performances, and her accompanying live music ensembles included anywhere from seven to twenty musicians.¹⁶ Dance innovator and teacher Ibrahim Farrah said she was his “greatest personal inspiration” and called her “the greatest cabaret Oriental dancer in the Middle East.”

She encouraged dancers to eschew the term “belly dance” to describe what they did, in favor of either raqs sharqi or Oriental dance. According to an interview with Arabesque in 1976, she choreographed all of her dances, even the taqāsīm, a great contrast to the improvisational dance of her predecessors.¹⁷ She claimed that this approach elevated Oriental dance as a stage art; in fact, because of her artistic and expressive performances, she was often called “the queen of polite dancing.”¹⁸ Like many other famous Oriental dancers, she emphasized understanding the music of the Middle East, including its rhythms, culture, and origins, as well as constant training and study of the dance.¹⁹ She died in 1990 at age 53 of breast cancer and complications related to pneumonia.²⁰

Mona El Said

Born Mona Ibrahim Wafa, Mona El Said was at the Suez Canal to parents from the Sinai oasis of Musa. The 1967 Arab-Israeli (Six-Day) War forced her, her mother, and sisters to take refuge in Cairo. It was at a disco there where the owner of the Sahara City nightclub saw Mona’s talent for dancing and encouraged her to do it professionally. Defying her mother’s admonition against it, she began dancing at Sahara City when she was thirteen years old. When her Bedouin father heard the news, he threatened to kill Mona, forcing her to flee to Beirut, Lebanon, in 1970, where she lived and performed.

In 1975 Mona returned to Cairo, dancing at the openings of many famous nightclubs including at the Meridian Hotel and El Gezirah Sheraton. With a Turkish business partner, she bought the exclusive Omar Khayyam nightclub in London where she performed in the late 1970s. In the early 1980s, she performed again in Cairo, married an Egyptian man in 1985, moved to London, and stopped dancing for one year. She returned to dancing in Cairo in the late 1980s. At the dawn of the age of home video, Mona El Said’s was one of the first Egyptian performances available in the early 1980s.

Considered one of the great dancers of the 1970s and 1980s, Tahiya Carioca nicknamed her the “Princess of Raqs Sharqi” and Egyptian media nicknamed her “The Bronze of the Nile.” She always performed with a large orchestra, and she starred in a number of Egyptian films. In the 1990s, she managed and owned a co-ed health club in Cairo, while continuing her career as a master instructor and performer. She is also a pioneer of the touring Oriental dancer, having taught workshops and performed around the world, which she continues to do today.²³

The content from this post is excerpted from The Salimpour School of Belly Dance Compendium. Volume 1: Beyond Jamila’s Articles. published by Suhaila International in 2015. This Compendium is an introduction to several topics raised in Jamila’s Article Book.

If you would like to make a citation for this article, we suggest the following format: Keyes, A. (2023). The Second Generation of Great Dancers. Salimpour School. Retrieved insert retrieval date, from https://suhaila.com/the-second-generation-of-great-dancers

1 Sharon R. Iverson (Shareen el Safy), “Reflections: Sohair Zaki,” Arabesque 8:5 (1987): 9.

2 Francesca Sullivan, “Sohair Zaki: Singing with her Body,” Habibi 19:1 (2002), also at http://thebestofhabibi.com/vol-19-no-1-feb-2002/594-2/.

3 Iverson, “Reflections,” 9.

4 Sullivan, “Sohair Zaki.”

5 Iverson, “Reflections,” 9.

6 Sullivan, “Sohair Zaki.”

7 Geraldine Brooks, Nine Parts of Desire: The Hidden World of Islamic Women. (New York: Random House Digital: 1995), 216.

8 Nimeera, “Sohair Zuki,” Serpentine Communications, accessed December 27, 2013, http://www.serpentine.org/yasmin/SohairZuki.html.

9 Sullivan, “Sohair Zaki.”

10 Franken, “Farida Fahmy,” 268.

11 Grace Pagano, “Nagwa Fouad: A Brand Apart,” Arabesque 6:5 (1981): 4.

12 Franken, “Farida Fahmy,” 268.

13 “Nadia Gamal: An Interview with the Artist—Part I,” Arabesque 1:5 (1976): 10.

14 “Nadia Gamal: An Interview—Part I,” 12.

15 The zār is a traditional trance ritual performed mostly by lower-income and peasant women in Egypt, Sudan, the Horn of Africa, and the Arabian Gulf states, as a means of ridding oneself of possession by jinn or other spirits.

16 Glenna Batson (Samira), “Nadia Gamal: An Interview with the Artist—Part III,” Arabesque 2:1 (1976): 8.

17 Glenna Batson (Samira), “Nadia Gamal: An Interview with the Artist—Part II,” Arabesque 1:6 (1976): 16.

18 Batson, “Nadia Gamal: An Interview—Part II,” 8.

19 “Nadia Gamal: An Interview—Part I,” 13.

20 For an entertaining and anecdotal look at Nadia Gamal’s life, see Randall Grass, Great Spirits: Portraits of Life-Changing World Music Artists, (Jackson, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi, 2009), 201-223.

21 Pagano, “Nagwa Fouad,” 4.

22 See also: Yasmina of Cairo, “At Home with Fifi Abdou,” Gilded Serpent, July 29, 2009, accessed December 29, 2014, http://www.gildedserpent.com/cms/2009/07/29/yasminacfifi.

23 See also: Shareen El Safy, “Mona El Said: Moving in Mysterious Ways,” Habibi 15:1 (Winter 1996), accessed December 13, 2013, thebestofhabibi.com/vol-15-no-1-winter-1996/mona-el-said/; and “Mona El Said,” Mona El Said, accessed December 13, 2013, sites.google.com/site/monaelsaiddance/.