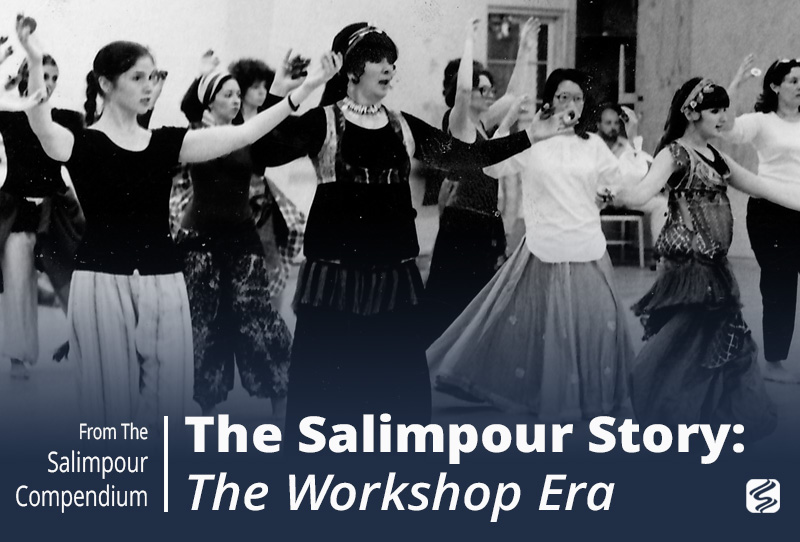

Somewhere between 1973 and 1975, I began producing two-day workshops in which I presented other teachers to my students and other dancers with a show in the evening.

Soon after, Jamila held her first weeklong workshops at her Broadway studio, and participant dancers stayed at the nearby Sam Wong Hotel (now reinvented as a high-end boutique hotel by the name of SW Hotel). On the weekends, Jamila rented a bus to transport the twenty-to-thirty participants around the Bay Area to various vendors. In the evenings, students would visit the clubs to experience the local music and dancing scene.

When I began offering my five-day (weeklong) workshops I presented my format exclusively, and my advanced students helped teach. Later, I included featured guest instructors. I also sponsored lead dancers from Egyptian folkloric troupes such as Lala Hakim, Faten Salama, and Shawki Naim. It was very important for me to have all styles available to my students so that they could explore them. The dance was growing and so was our school. One week I would have a Guedra workshop, the next Suhaila would teach the choreography she learned from Nadia Gamal.

Over several years, Jamila hosted many guest teachers to give workshops at her 471 Broadway dance studio, as well as to teach at her weeklong workshop events. These dancers included Zenouba, Hassan Wakrim, Helena Vlahos, Ahmad Jarjour, Ibrahim Farrah, Morocco (Carolina V. Dinicu), Vashti (Dallas), Dahlena, Anthony Shay, Ali Jihad Racy, and more. Suhaila studied with all of the teachers whom her mother sponsored. Although the weeklong workshop concept was new to belly dance, other dance forms had already been employing it. Jamila got the idea from and based her weeklong workshops on the same format she saw used in summer workshops that Suhaila took for jazz, ballet, and tap dance. One particular example was the Al Gilbert (Allesandro Zicari) summer dance camps that Suhaila attended two years in a row around the time she was nine years old.¹ Area dance schools typically enrolled several students in the camp, and the studio teachers would attend as chaperones; students from each school tended to stick together throughout the week without mingling with other dancers from other studios. Suhaila, being the only student from her “school,” felt isolated from the rest of the students, especially since her studio chaperone also happened to be her mother.

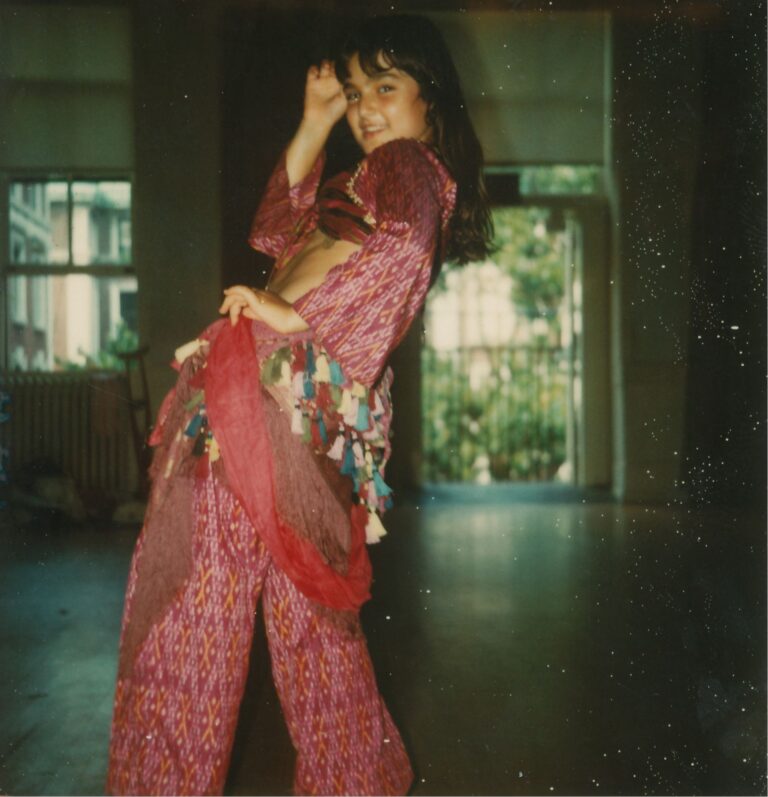

In the early 1970s, Jamila began seeing the effect of Suhaila’s Western dance training (ballet, jazz, and tap) on her format’s step families,² providing a Western body line and framework upon which to layer the belly dance moves. Jamila felt that the basic fundamentals from Western dance training were necessary for belly dancers. Jamila was frustrated that her dance skills would never reach the level she wanted to interpret the way she heard the music; she could not duplicate the dancer in her head herself. She encouraged her students and teachers to begin studying ballet and jazz. Many of them refused, feeling that ballet and jazz would “take away” from the dance. Jamila explained it would take time (even years) to integrate the two together properly and that it might be awkward at first, but many dancers did not want to “start over” in their training.

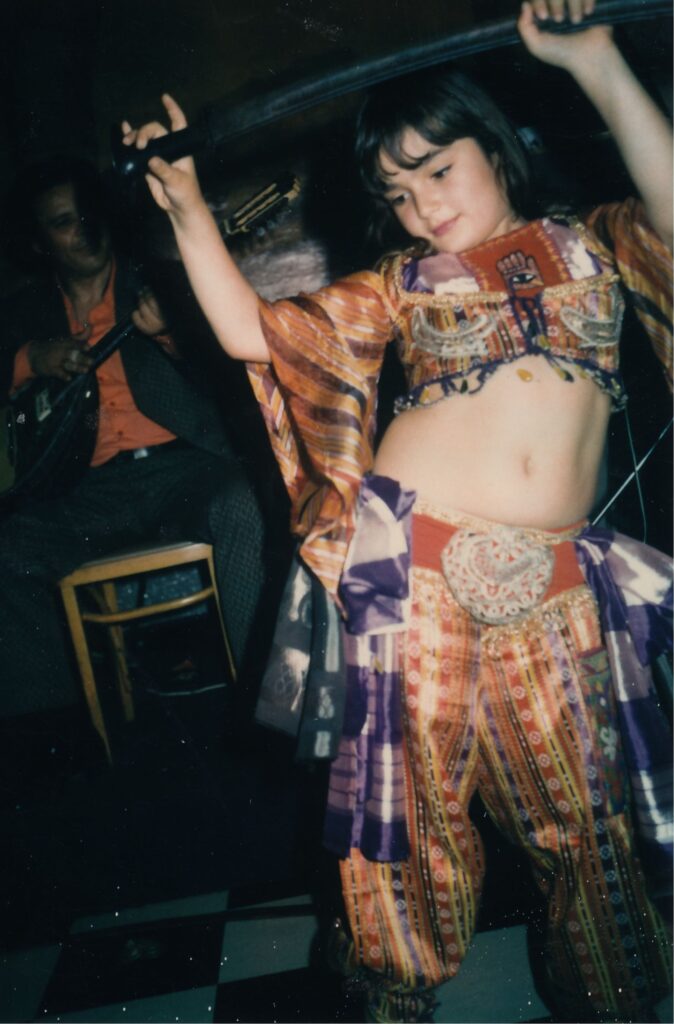

By 1976, at nine years of age, Suhaila became the primary teaching assistant in her mother’s classes and workshops. When they taught together, Jamila would explain a step, and Suhaila would break down the reverses and variations. Jamila often said that Suhaila was better at explaining and breaking down the steps because Suhaila would use both her mother’s format language and terminology from her other dance training. Interestingly, Jamila did not teach Suhaila directly; instead, Suhaila picked up her mother’s format by sitting and observing the classes and performances when she was a small child. Around this time, Suhaila created her first choreography of “Walla Zaman,” a song sung by Metkal Kenawi. Before this time, everything she had done was improvised, and this was her first effort to listen to the music and apply steps to the music structure.

In the summer of 1976, after Ardeshir died, Jamila wanted to escape the area for a while. Jamila and Suhaila traveled by train to teach workshops across the United States and Canada when Suhaila was on break from school for the summer. They also visited Ahmad Jarjour at his home in Montreal; and ended their trip with a visit to their long-time family friend Bob Gary in Los Angeles. It was on this trip that Suhaila and Jamila met with Ibrahim Farrah in New York City to see his film footage of Nadia Gamal.³ Nadia’s dancing confirmed for Jamila her feeling that a Western bodyline was essential; Jamila also felt that she, Jamila, was no longer a sufficient representative of the dance. The training Suhaila was receiving and integrating was the answer.

Suhaila continued choreographing and by the time she was 12, she had further fine-tuned “Walla Zaman,” but also created four solid choreographies collectively called “The 12-Year-Old Dances” to the music of Aboud Abdel Al. These showed Suhaila’s efforts to represent the music in phrase, breath, and overall composition rather than just choreographing 8 counts of this and 8 counts of that. You can see steps such as Salaam Step in a Circle included in these dances that demonstrate Suhaila’s contributions that were then integrated into her mother’s format.

Jamila and Suhaila continued to travel and teach workshops every summer every year through 1980 when Suhaila was 13. After they filmed the first three volumes of what is now published as the Jamila Salimpour Format Archive Series, in which Suhaila taught her mother’s format on three video cassettes, they ended their long summer touring. They filmed the fourth volume, “Folkloric Steps,” in 1983 during Suhaila’s junior year of high school when she was 16 years old; most of these steps are included in what is now called the Salaam Family of the Jamila Salimpour Format. In these recordings, Jamila felt that dancers had a resource they could use and study over time.

Meanwhile, in analyzing, writing down, and cataloging as much as I could remember, the accumulation of information created a vast repertoire for my students to draw from and to enable them to analyze, notate, and create on their own within the form. I had a large amount of information accumulated and so I published a manual in 1978. It was important to me to preserve the complicated hipwork of my generation. I also cataloged finger cymbal patterns, releasing an audiotape with 24 patterns and a booklet with the history and notation of 47 patterns. In 1980, I put my format on several videos with Suhaila demonstrating.

But Jamila was facing issues within her studio. One of her biggest complaints was that so many students attended classes for a few months or a couple of years and then left, convinced they had what they needed to succeed in the world of belly dance. Because the dance form was still so young, they probably did not have enough to succeed as performers. Jamila expressed her disproval when people left before she felt they had learned everything she had to offer, and she was often openly critical of students who studied but never returned to the source to continue their education. One of Jamila’s biggest regrets about Bal Anat was that she put students on the stage too soon, as students often equated being on stage with being advanced or professional dancers who no longer needed additional training.

Jamila was also frustrated by the lack of interest from her students and the local dance community when she sponsored Egypt’s dancers. Although Jamila did not particularly favor the stylization—in her initial anticipation of seeing the folkloric dancers, Jamila presumed their stylization might resemble the earthy Bal Anat, but was surprised to see a very strong ballet influence—she felt it important to learn from these dancers and stay connected to the current dance in Egypt.⁴ She believed the lack of support was due to fear of having to learn something new that might show a dancer’s weaknesses, thereby jeopardizing a dancer’s position as a “professional.” Emphasizing her point that too many students left their teachers too soon, Jamila maintained that a dancer with enough training and experience could more easily learn and integrate new stylizations without feeling threatened.

Jamila was a taskmaster. She was known for being “hardcore” and demanding that her students give 100%.⁵ She wanted all of her assistant teachers and advanced students to study ballet so they could integrate the Western bodyline. One of her main teachers argued that new was not necessarily better, which became a slogan of those who opposed Jamila’s directive. Affronted that some of her students countermanded her decisions and caused dissension, Jamila closed her studio on Broadway in 1980.

With the publication of the Archive Series videos and Suhaila’s instruction, Jamila felt that students had access to high-quality training. By the time she was 14, Suhaila had taken over teaching all of the weekly classes, and Jamila handled registration. When the Broadway studio closed, Jamila rented space at several area studios so that Suhaila could teach belly dance and tap. Suhaila eventually taught the main Jamila format classes on Saturdays at the old Sears Building in San Francisco.⁶

Suhaila also took over teaching all the workshops outside of Northern California. Jamila would organize contracts with existing sponsors she trusted to take care of her teenage daughter. Suhaila rarely missed school on Fridays and Mondays to teach weekend workshops out of town; she took red-eye as often as possible and finished her homework on the plane.

Also in 1980, Jamila moved her weeklong workshops to a hotel; she first held her event at the Holiday Inn and Ramada Inn, both at Fisherman’s Wharf. On the weekend, she held a festival she named the Great Eastern Faire, which featured vendors and performances. She brought the vendors to the venue, rather than renting a bus to visit them. She named the event Work and Play in Bagdad by the Bay. Festival performers—who auditioned for the opportunity—danced from late morning until the evening. Jamila’s weeklong workshops were an innovative means of presenting belly dance instruction and vending; soon after, others mimicked the structure. In the last years of producing events, she held them at the upscale Bellevue Hotel (now Hotel Monaco) on Geary Street, near Union Square in San Francisco. Jamila continued her weeklong workshops and festivals until 1985; in 1999, Suhaila revived and reestablished her mother’s weeklong workshop concept

The desire to perform, professionally or not, was the impetus for the “festival format” of continuous but planned dancing throughout the day. I developed this structure to give my students, the students of my students, and their troupes an opportunity to get together, shop, eat, perform, and watch other dancers until they dropped.

In 1980, Suhaila began taking private dance lessons with Yuki, a well-known jazz teacher in Castro Valley. Suhaila writes: Taking with Yuki was a light bulb moment for me. I was incredibly inspired by Yuki’s phrasing and movement quality, and I began seeing jazz a bit differently. By this time, I already had ten years of jazz in my body and even more of belly dance, and the two dance forms had started fusing and melding naturally. And I already noticed that this organic development was happening. After talking with Yuki, I started playing a game: “How do I ‘bellyize’ this move?”.

Having watched and studied dancers for many years, Jamila observed subtle changes in technique from the Egyptian dancers. Noticing the emergence of a new style, she sent Suhaila (when Suhaila was 14 and 15) to Egypt in the summers of 1981 and 1982 both to research the emerging trends and to explore options for a costume import business. What we now call “Modern Egyptian Style” was just beginning to emerge in Cairo. Egyptian music compositions also began changing; selections were grander with more complex orchestration, phrasing, and structure.

In 1981, when she was a freshman in high school, Suhaila skipped school one day to take the bus to Berkeley and buy a video cassette player—for which she paid $1200, using money she had saved from teaching—for her mother; the player was in both Betamax and VHS formats. VHS tapes of dancers were imported from the Middle East, and now they could study performances (Nagwa Fouad, Mona El Said, Sohair Zaki, and many others) as many times as they wanted. Suhaila would break down the phrases and isolate the movements so she could teach them to her classes. Although Jamila’s format was the base, Suhaila added elements she observed from the great dancers.

As Suhaila was growing up, so was the age of video. Now for the price of a video rental, you could transport yourself to the hot nightclubs and hotels in the Middle East, seeing firsthand the latest trends and movements. Americans were now able to tap into the Middle East and not just do our version or interpretation of the dance. This was a turning point in the Salimpour School. When Suhaila was a young teenager, teaching on her own with her trained bodyline, she combined her traditional training in my method with the new direction from Egypt.

The dance began changing in America when Egyptian dancers visited, bringing their own orchestras. Sohair Zaki and Nagwa Fouad brought musicians who played complicated musicals that we had never heard before. Videos were being made available to us, featuring Oriental dance interpretations of modern musical compositions. We watched the Reda Troupe, Sohair Zaki, Nahed Sabri, Hanan, Mona El Said, and many more. The dance in Egypt was evolving and the Russian presence was felt with the inclusion of ballet as a prerequisite to dance in the national folkloric companies. Members of these companies began choreographing for well-known cabaret dancers.

Jamila and Suhaila were inspired by the new Egyptian stylization, the changes in the music, and Nadia Gamal’s use of Western training to supplement her music interpretation. And Suhaila was also influenced by her studies of various dance forms (ballet, jazz, tap, Hawaiian, and Flamenco) including the “funk style” street dancing that she observed at Fisherman’s Wharf in San Francisco for several years. In 1982, she was inspired by the Gentleman of Production performing a style known as Oakland Boogaloo and then studied popping and locking with one of their members, Walter Freeman.⁷

Together, Jamila and Suhaila would characterize the music, and Suhaila would use her knowledge of her mother’s format along with her other dance training to choreograph and bring the characterization to life. Their first collaboration was “Joumana.” Suhaila worked every day after school over the course of about a week to choreograph “Joumana.” Suhaila writes: I choreographed the piece in our living room (on a white shag room-sized rug), watching my reflection in the window. Suhaila finished the choreography in 1982 and debuted it at a local dance studio recital. Suhaila then successfully auditioned with “Joumana” for the San Francisco Ethnic Dance Festival (EDF) in 1983 and was the first dancer to represent Middle Eastern dance at the prestigious event.

Jamila and Suhaila collaborated on two more choreographies, “Maharajan” and “Hayati,” which Suhaila performed at EDF in 1984 and 1985, respectively. And it was in 1985 that Suhaila’s use of the gluteus muscles for hipwork began to show more prominently in her dance.⁸

Suhaila writes: “Joumana,” “Hayati,” and “Maharajan” are three choreographic projects that represent my best creative collaborations with my mother. When my mother would mention a general concept or quality or mood, I was able to create it in dance; it was like a telepathic connection between us. And it was for these projects that she completely trusted my instincts. My training in ballet and jazz expanded my mother’s belly dance format exponentially, and she could see how the training was necessary to realize the ideas she had in her head that she, herself, was not capable of fulfilling. Jamila never wanted to limit her students or me, so she was supportive of me taking the dance further and encouraged me to do so.

Suhaila writes: “Joumana,” “Hayati,” and “Maharajan” are three choreographic projects which represent my best creative collaborations with my mother. When my mother would mention a general concept or quality or mood, I was able to create it in dance; it was like a telepathic connection between us. And it was for these projects that she completely trusted my instincts. My training in ballet and jazz expanded my mother’s belly dance format exponentially, and she could see how the training was necessary to realize the ideas she had in her head that she, herself, was not capable of fulfilling. Jamila never wanted to limit her students or me, so she was supportive of me taking the dance further and encouraged me to do so.

In 1985, Jamila ended her weeklong workshops and mostly retired. She stays connected with old friends and students, continues writing about her research, and occasionally teaches master classes. She is unreservedly supportive of Suhaila’s developing technique and method that built upon Jamila’s foundation and then expanded it exponentially. Jamila truly believes that proper integration of Western techniques is the answer to elevating the dance form. Jamila focuses her energy on her continued research of the history of the dance form and on promoting Suhaila’s integrated format as “the Future” of Oriental dance.

The content from this post is excerpted from The Salimpour School of Belly Dance Compendium. Volume 1: Beyond Jamila’s Articles. published by Suhaila International in 2015. This Compendium is an introduction to several topics raised in Jamila’s Article Book.

If you would like to make a citation for this article, we suggest the following format: Totten, V. (2023). Salimpour Story. The Workshop Era. Salimpour School. Retrieved insert retrieval date, from https://suhaila.com/the-salimpour-story-the-workshop-era

¹ Al Gilbert’s business was called Stepping Tones. He created a comprehensive tap dictionary and tap syllabi for instructors. He wrote songs and choreographed them, licensing them to studios to use. At the camp, a selection of his choreographies would be taught, and the camp would end with a performance by the students. Suhaila attended his camps in Los Angeles and San Diego.

² In addition to her Western dance training, Suhaila studied Tahitian and Hawaiian dance at a local dance studio in Richmond, California, between the ages of seven and nine. When she was 10, she began studying Flamenco, and when she was 12, she began studying with Rosa Montoya, a Flamenco matriarch who founded her studio and dance company in San Francisco in the early 1970s. Montoya has since retired in her home country of Spain.

³ Suhaila also studied with Bobby Farrah as much as possible during her visits to New York City and his visits to the West Coast. She enjoyed the folkloric work and later studied extensively with Mahmoud Reda when he came tour to the United States sponsored by Ali of Turquoise International in the early 1990s. Suhaila and Reda even attended tap dance classes together.

⁴ In general, folkloric dance was popular on the East Coast of the United States beginning in the 1970s due to the efforts of Ibrahim Farrah; the West Coast began taking more interest in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

⁵ Jamila had several nicknames from her students including Mama J, The Fortress, and the Dragon Lady.

⁶ An old Sears retail store located at 3435 Army Street (now 3435 Cesar Chavez Street) in San Francisco was converted for small offices, artist lofts, and dance studios in the 1970s.

⁷ Walter “Sundance” Freeman later became a featured tap dancer in the world-famous Irish dance production Riverdance on Broadway for nearly a decade.

⁸ As a child, Suhaila realized that she could use her gluteus muscles for her hip work, thus allowing for more layering opportunities. In 1981, Suhaila was inspired by Prince’s album Controversy, and she began developing her gluteus technique and method to that music. While completing her homework after school, she squeezed her glutes (singles, alternating, and syncopated to various timings and tempos) to the entire album. She continued fine-tuning her method to Prince’s subsequent albums, 1999 in 1982, and Purple Rain in 1984.