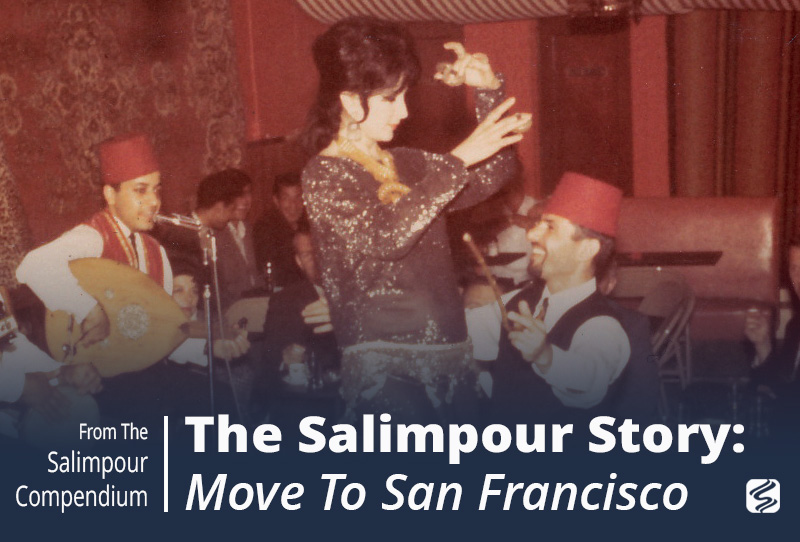

Tired of traveling back and forth between two cities, Jamila decided to move to San Francisco permanently. Jamila stayed in the New Rex hotel, as did Yousef and most of the dancers. The hotel was more of a boarding hotel. Residents had private rooms, but shared the bathrooms down the hall.

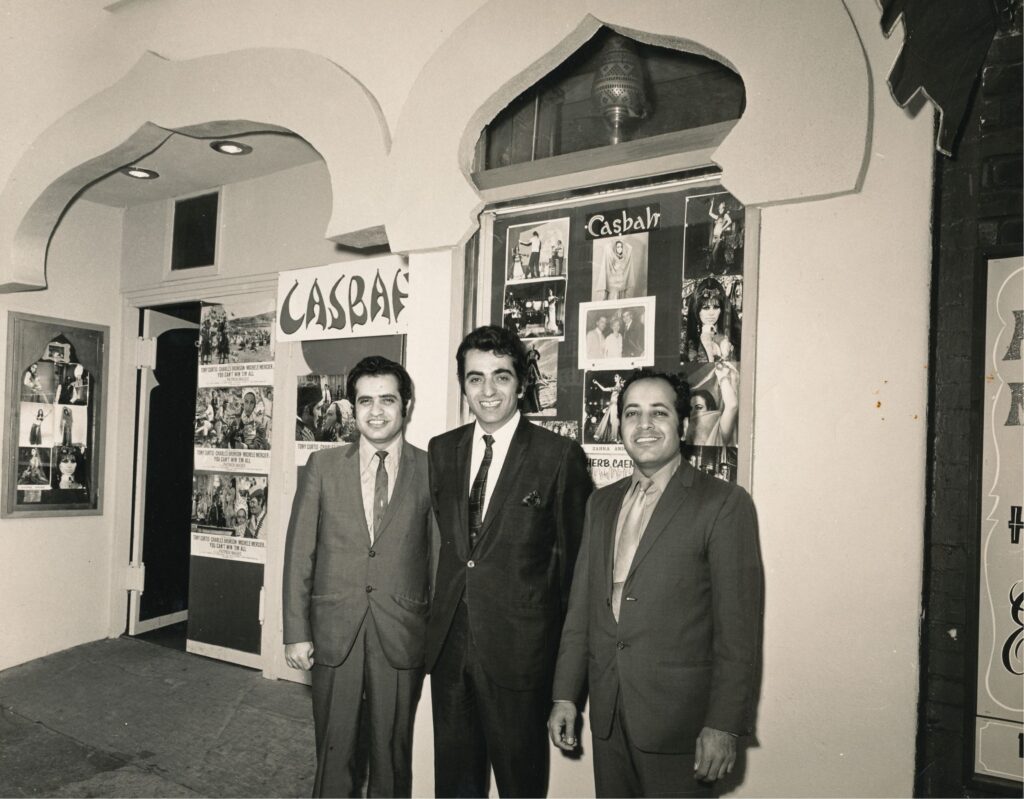

Around the corner from 12 Adler Place was a struggling Greek club on Broadway Street in San Francisco; Yousef decided to buy it and open his own Middle Eastern club in its place. Jamila became a partial owner and contributed monetarily to the opening of the club; to do so, she took out a second mortgage on her car, which was possible at that time. As Yousef was not a US citizen, having Jamila as an owner helped the club obtain a liquor license. They named the club the Bagdad Cabaret, and the pair got engaged.

Jamila on Claresa Degian

After I moved to San Francisco, Claresa auditioned at 12 Adler Place. Although she was a good dancer, the management did not offer her a job; the close proximity to the crowds, combined with the harsh stage lights emphasized her chicken pox scars. I lost touch with Claresa, and I found out a few years later that she had returned to her family, consented to marrying an Armenian man, and had a baby boy. After two years, she left her husband; she began organizing a cross-country dance tour, planning to take her son with her. Her father-in-law called her to his home and confronted her. He told her that she had disgraced the family. He asked if she was going to continue working as a dancer and if there was anything he could do to change her mind. When she replied that she did plan to work as a dancer and there was nothing he could do to change her mind, the father-in-law pulled out a shotgun and murdered her. Although he was convicted and sent to jail, his family and community exalted him as a protector of his family’s honor.

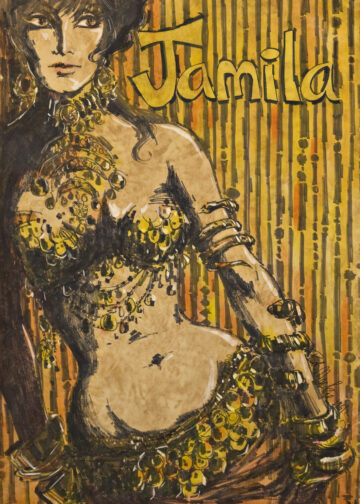

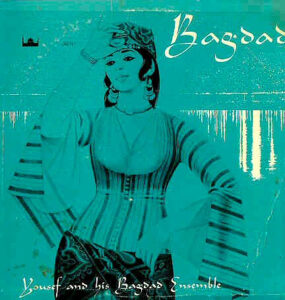

Yousef hired the bar staff and handled inventory. He also played violin in the band, and even recorded his own albums; Yousef’s first album, Bagdad by Yousef and His Bagdad Ensemble, features a drawing of Jamila by dancer and researcher Leona Wood. Jamila hired and scheduled the dancers, and she was a hostess when she was not performing. Jamila taught private students at the club, usually at 5 p.m. each evening. Together, they traveled to Los Angeles about once a month to recruit new dancers. The Los Angeles dancers were often quite happy to dance in San Francisco because the clubs there paid more than in southern California.

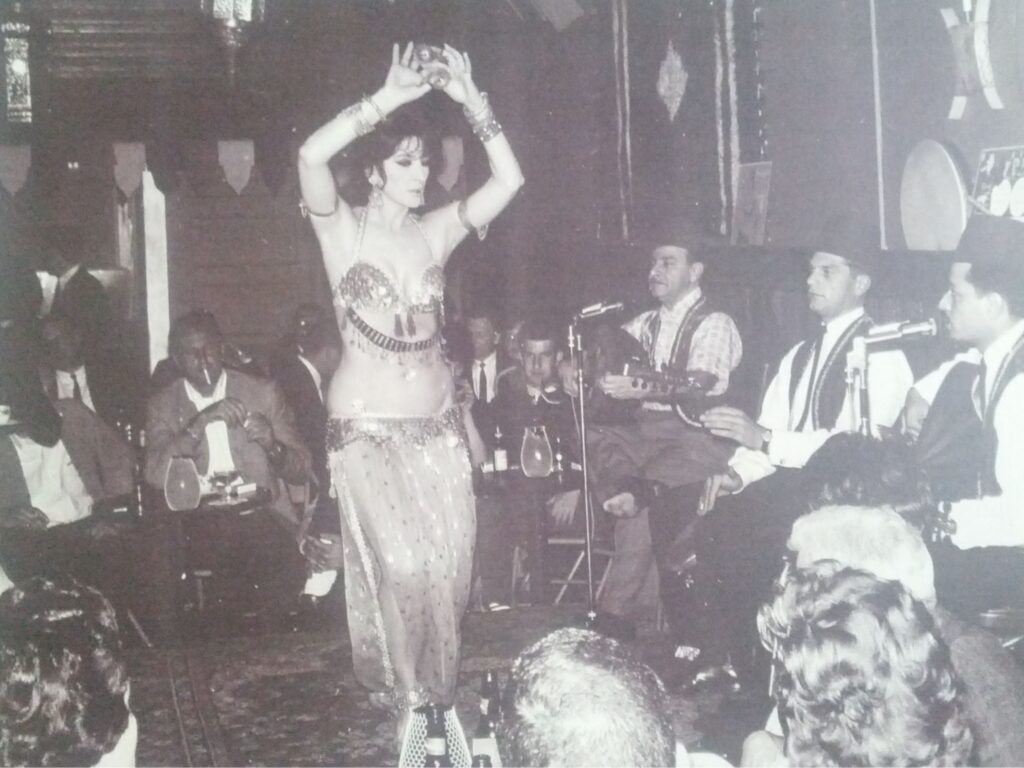

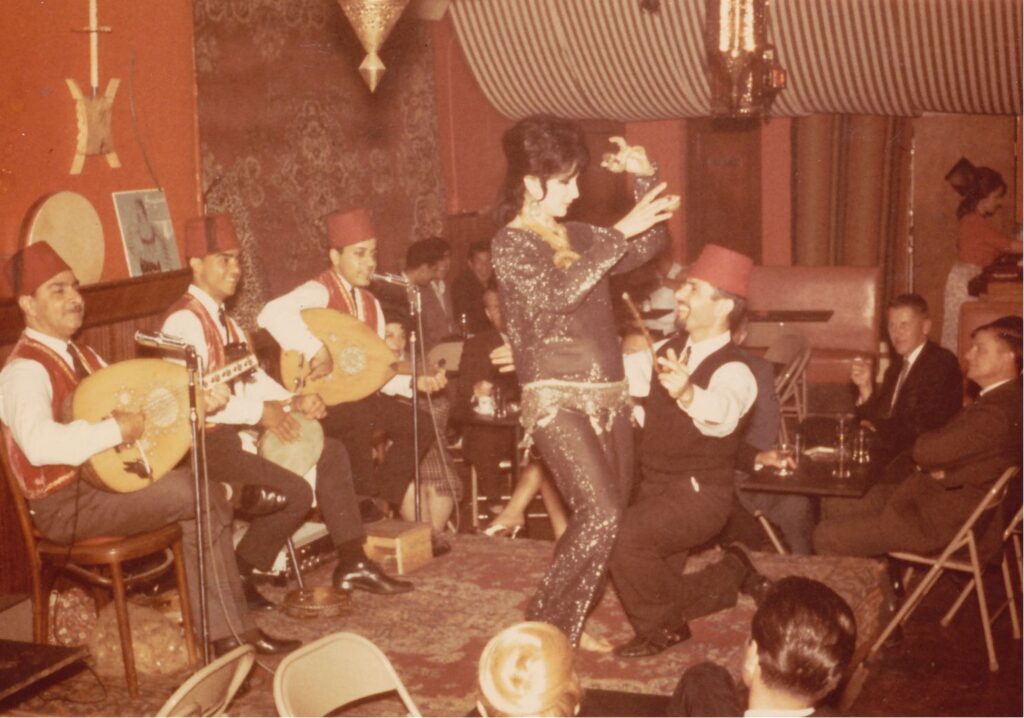

The Bagdad served alcohol and pretzels only, and the bar was on a raised stage that jutted out from one of the walls. A bar counter surrounded the outside of the stage, so patrons could sit on bar stools around it. A few booths were situated along one wall, and additional small tables with chairs and bar stools were scattered about the venue. The performers had a changing room upstairs. The clubs typically had a doorman who doubled as a security guard or bouncer, and the cover charges were around $2. In the early to mid-1960s, dancers stayed on the stage and did not perform directly amongst the customers as many did in the late 1960s.

Regulars at the Bagdad included Charles M. Shultz,¹ an up-and-coming cartoonist; well-known members of the Hell’s Angels; and Walter Keane,² who became known for his kitsch paintings of wide-eyed waifs. Lenny ³ also dropped in regularly when he was in town performing in North Beach.

From the late 1940s to the late 1950s, Middle Eastern music and dance were virtually unknown to Americans. However, it flourished in small pockets where immigrants representing a variety of countries from the Arab world would gather together to celebrate social or religious customs. Their nationalities were a common bond, and, whenever they met, music and dance were included in their festivities.

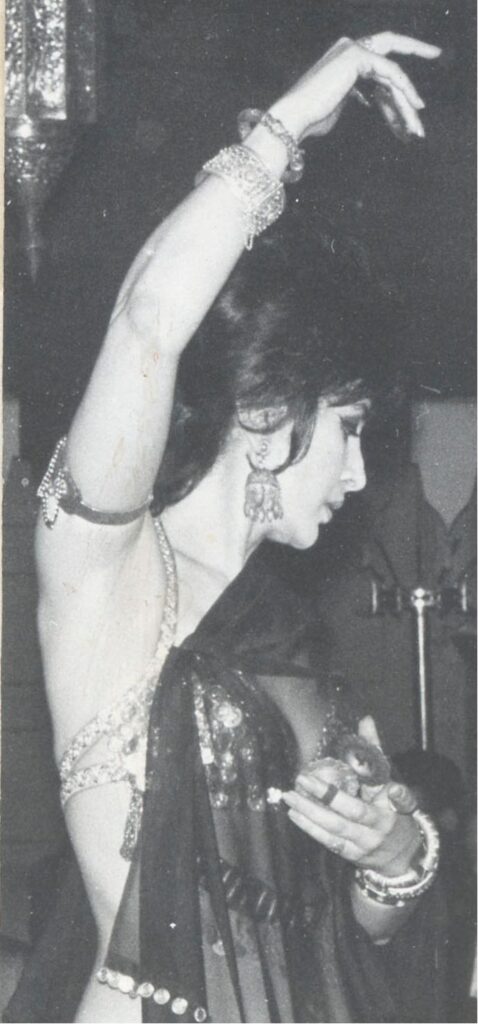

It was only after I went to dance in San Francisco, where dancers were hired from different countries, that I saw a variety of styles. We worked in the same club and imitated each other’s specialties, of course, not in the same show, and usually only after they’d left town. Turkish Aisha wowed the audience with her full-body vibrations. During her show, I would run to the dressing room to analyze her pivots. Soraya from Morocco danced almost always in a baladi dress, balancing a pot on her head. Fatma Akef [Naima Akef’s sister] danced on water glasses with her parrot, Laura, perched on her shoulder. Nargis did the most incredible belly rolls, and her entire finale consisted of continuous Choo-Choos. Fatma Ali did a 4/4 Shimmy on the balls of her feet; I was told by Mohammed El Scali that she was an Ouled Nail, and she had what looked like a large knife scar on her face. And so it went, show after show, night after night, year after year.

Yousef wanted variety in the dancing acts at the Bagdad in an attempt to echo shows at Badia Masabni’s Casino Opera in Cairo. In addition to the dancers with various props, one of the drummers, Ismail Khalifa also did a magic and comedy act; he later performed as a magician, nicknamed Gilly Gilly, with Bal Anat at the Northern California Renaissance Pleasure Faire.

One of the most popular gimmicks at the nightclubs was known as “the Sultan Act,” in which the featured dancer would invite an audience member on stage with her. The dancer would then, if the audience member was a man, wrap her veil around his head like a turban, or if the audience member was a woman, drape her veil around the woman’s neck. The dancer would then teach the person a few dance moves to imitate. The rest of the audience would laugh, and the shtick ended quickly. In the 1960s, these acts sometimes became provocative and sexually suggestive. Jamila integrated the gag into Bal Anat’s early performances at the Northern California Renaissance Pleasure Faire, but she took care that it remained family-friendly.

Most of the bands in these California nightclubs featured three instruments: drum, ‘ud, and tambourine. Sometimes a violinist or qanun player would join the ensemble, but instruments requiring electric amplification were rare.

Since the musicians were mostly amateurs and from a variety of Arab countries, the music was haphazard. Rarely did they know the same piece, often going in different directions, and they practiced during the show. Rehearsals were unheard of. Musicians were in short supply so we couldn’t complain. You could replace a dancer easier than a musician.

All of the musicals we danced to were in 4/4 rhythms with wahda-wa-nos for taqsim. Musicals like “Aziza” with breaks and changes in rhythm were then only played between shows. A drummer at the Bagdad taught me how to play longa (finger cymbal pattern), which is right-left-right, the counts being one and three on the right hand.

Although Jamila had learned as much as she could about finger cymbals from watching dancers in the nightclubs and Egyptian movies, she now considered them as separate from the drums. She intuitively and naturally learned rhythm and syncopation, aided by her early days attending shows at the Apollo Theater and studying tap dance. Like a jazz musician, she began documenting finger cymbal patterns that coordinated with Middle Eastern drum rhythms and melodies.

Jamila began mentally categorizing the dance steps and movements she saw the other dancers use in their shows, steadily building her format. In addition to noting the different steps, Jamila noted patterns, themes, and variations

The Algerian dancers balanced pots on their heads and also did extensive floorwork. In addition to her Turkish Drop and Stomach Flutter, Jamila wrote that Tabora Najim’s “veil work was unique and choreographed, and she ended all her shows with an exciting karşilama.”

In Los Angeles, where Arabs made up a large part of the audience, the performances were short and in three parts: entrance, taqsim, and finale. Arabs came to hear the musicians and singers rather than to see the dancers. In San Francisco, the mostly American audiences came to see the dancers. They didn’t understand Arabic so the songs meant nothing to them. The owners said that a girl onstage brought in the customers, so now it was three dancers back-to-back, three shows a night. Owners wanted a dancer on stage at all times; what were originally 15-minute sets expanded to 30- and 45-minute sets.

As time went on my specialty became a finger cymbal and shimmy solo, which I performed without music, using my coin girdle as a percussion instrument, interspersing shimmy rhythms with finger cymbal variations. I mentally noted 4/4 Shimmy, Choo-Choo, and 3/4 Shimmy while practicing my coin solo.

Never having had any formal dance training, I learned Oriental dance in the old way: by watching and imitating. There were no schools or teachers. I gleaned whatever I could from anyone who would show me they knew anything. After having seen so many different dancers with individual movement specialties, I began first analyzing and then mentally cataloging my observations. It became apparent that a dancer danced her style depending on the country from which she came and the provincial influences she was exposed to that crept into her dance.

Late in my career, I met a dancer who was having successful engagements with a style foreign to most of us. Rushing her entrance, most of her dance was done on her knees while twirling her head, working herself into a frenzy to the delight of audiences. She was from Jordan and had participated in many a women’s get together in which they all twirled their heads. We came to know this dance as the zār. When she came to perform in San Francisco, she asked me for instruction, and I gave her as much information as her stay allowed before she had to move on to engagements in other cities. No matter where she danced, her routine predominantly focused on the zār. In no other part of the dance did she become as emotional as the taqsim when she could emote and literally put herself into a trance.

Jamila first met Ardeshir Salimpour⁴ when she was 37; he was 16 years her junior. He had been a drummer at the Bagdad for some time but had been dating another dancer when Jamila was engaged to Yousef Kouyoumdjian. Eventually, Jamila and Yousef ended their engagement because Yousef was not ready to settle down with one woman. Jamila soon began dating Ardeshir; they married in 1966 when she was 40 and he was 24.

North Beach also underwent changes right around this time. In 1964 the Condor Club opened in North Beach (corner of Broadway and Columbus) near the Bagdad, and it featured jazz acts along with a trick grand white piano that was lowered and raised by hydraulics from the main stage to the ceiling. The Condor was the first topless club in the United States, and featured Carol Doda, who was one of the first celebrities to undergo breast augmentation surgery. Tourists and locals poured in the club to see the spectacle of her silicone implants.⁵

Several other Middle Eastern clubs opened in North Beach and nearby along with burlesque, gay, and strip clubs. Some Middle Eastern nightclubs added barkers (persons hired by the clubs to stand outside and entice potential customers to enter the establishment ) to compete with the burgeoning entertainment venues. Also, belly dancers began stepping off stage into the audience to perform around the tables. In the early days of the Middle Eastern nightclubs, dancers often signed with an agency and joined a union, but the influx of dancers in the late-1960s meant that clubs no longer needed to hire dancers through unions or agencies. The increase in dancers also coincided with a decrease in pay.

The content from this post is excerpted from The Salimpour School of Belly Dance Compendium. Volume 1: Beyond Jamila’s Articles. published by Suhaila International in 2015. This Compendium is an introduction to several topics raised in Jamila’s Article Book.

If you would like to make a citation for this article, we suggest the following format: Totten, V. (2023). Salimpour Story. Jamila Moves to San Francisco. Salimpour School. Retrieved insert retrieval date, from https://suhaila.com/the-salimpour-story-jamila-moves-to-san-francisco

¹ Charles “Sparky” M. Shultz (1922-2000) was best known for writing and illustrating the Peanuts comic strip. Jamila also met Connie Bouchet (1924-1995) who collaborated with Shultz on the 1961 Peanuts Datebook and Happiness is a Warm Puppy (1962).

² After their divorce, Walter Keane (1915-2000) and his wife, Margaret, had a long running and public dispute over which of them created “the large eye” motif. Big Eyes, a fictionalized account of the artists’ lives, directed by Tim Burton, was released in American cinemas in 2014.

http://law2.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/bruce/brucecourtdecisions.html. The hungry i was a nightclub of great significant to the Beat Generation and considered instrumental in launching the careers of several great entertainers including Barbra Streisand and Bill Cosby. Debate exists over the name; Enrico Baducci who purchased the club in the early 1950s, said the name was an error; the name was meant to be “the hungry id,” referring to Sigmund Freud’s pleasure principle.

³ Born Leonard Alfred Schneider (1925-1966). Bruce, known for his stand-up comedy, developed much of his technique while working at the hungry i (the owners insisted that the name be lowercase) in San Francisco. Police arrested him in 1961 for using obscenity in his comedy act at the Jazz Workshop (located between the Bagdad and the Casbah); he had said the word “cocksucker.” Police in New York arrested him in 1964, again for obscenity. He and the club owners were convicted; the trial judge sentenced Bruce to four months in a workhouse. “Legal Opinions Relating to Obscenity Prosecutions of Comedian Lenny Bruce,” accessed March 7, 2014, http://law2.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/bruce/brucecourtdecisions.html. The hungry i was a nightclub of great significant to the Beat Generation and considered instrumental in launching the careers of several great entertainers including Barbra Streisand and Bill Cosby. Debate exists over the name; Enrico Baducci who purchased the club in the early 1950s, said the name was an error; the name was meant to be “the hungry id,” referring to Sigmund Freud’s pleasure principle.

⁴ Most belly dancers knew Ardeshir as Salim, his drummer nickname that was easier to pronounce. Jamila, however, always called him Ardeshir.

⁵ By 1969, the Condor Club dancers began dancing “bottomless” as well (term for completely nude). Then in 1972, the club returned to topless dancing due to a new California law making it illegal for completely nude dancing in places that served alcohol.