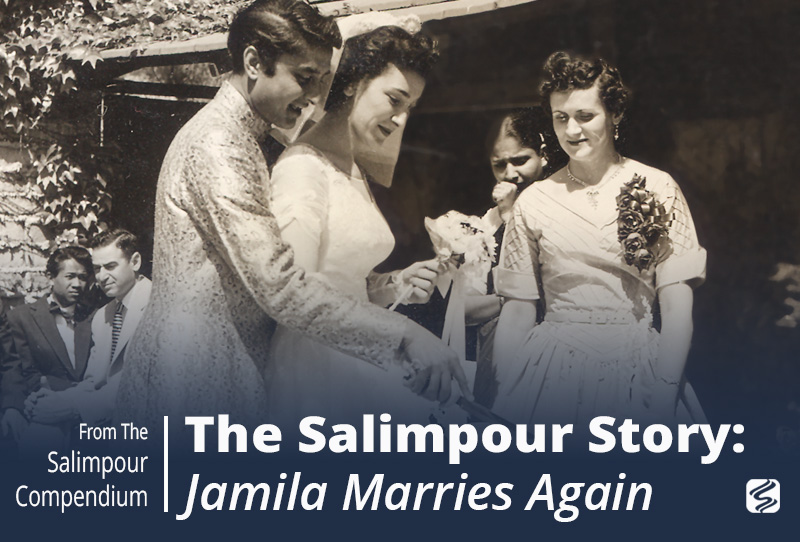

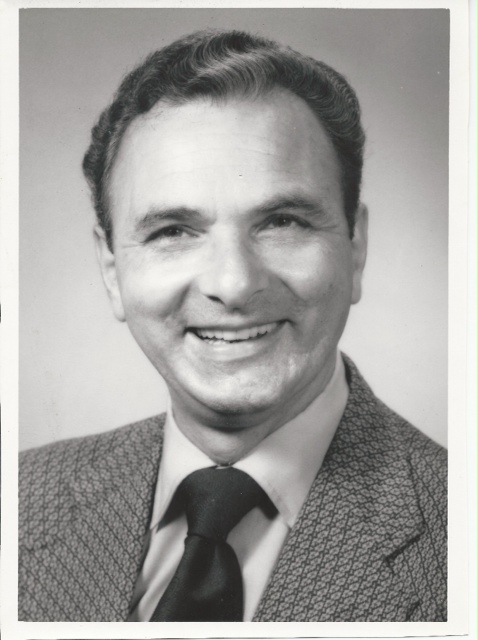

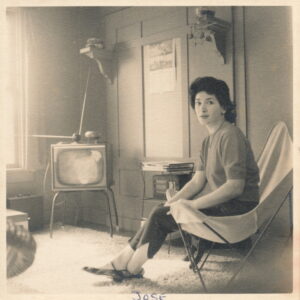

Jamila began dating Satya while Bob was in Mexico. Jamila and Satya married in 1953 when she was 27. Jamila found him very handsome and charismatic, and currently refers to him as Mr. Kama Sutra. When they first married, they had difficulty finding a place to live, as they were an interracial couple; mainstream American society in the 1950s disapproved of their union.

Meanwhile, Bob Gary returned from his film work in Mexico, but he found that Jamila was already married to Satya. Despite that, Bob and Jamila remained friends over the years. At various points in her life, Bob let Jamila (and later Suhaila) stay in one of the apartments on his property, and he was always there as a supportive friend. He never married. ¹

Jamila encountered difficulties in her marriage to Satya. He did not want her to make reference to anyone, especially to his friends, that she had worked with elephants during her time in the circus, because in India, the elephant trainers are considered “low caste.” In fact, he personally wanted to forget her history. Jamila burned her pictures from the circus in an attempt to please him.

He also disapproved of Oriental dance, asking me to forgo my pursuit of the dance since, as he put it, “One dancer in the family is enough.” Oriental dance was at the time considered indecent, so I gave in to his wishes and put my dance performances on hold. As there were no cabarets or clubs to perform in at that time, it did not initially seem a major sacrifice. Satya didn’t care for Oriental music either, or for that matter, anything but Indian dance and music, so for years my finger cymbals lay at the bottom of a paper mache bowl and eventually were covered with old letters. My collection of my ‘ud teacher’s 78 rpm records—collectors’ items and recordings of my teacher’s original taqsims —all melted together after being stored in the bathroom closet.

One of the few liberties Satya allowed me was to pose and model my Middle Eastern costume collection for students at the Chouinard Art Institute in Los Angeles.² Danny Reserva, an old friend, taught rendering classes there. Danny didn’t have a budget to pay for the models, so he would open the storage room where they kept props and tell us to take whatever we liked. I acquired a costume book;³ coin necklaces from Egypt; and, on one occasion, was given an etching (which I framed and hung on the wall) of an Egyptian ghawazi dancer performing with a sword on her head while holding another sword in her hand.

The late 1950s were no time for an Indian to find work in the movie industry; Satya worked in a bank, and I continued to make jewelry for Renoir. We struggled and saved hoping to someday open our own business. We imported hand-crafted furniture from India and attempted a lecture-demonstration of dances and customs from Indian villages; nothing ever materialized. And then on a fluke, we were offered the opportunity to buy a restaurant right across the street from Los Angeles City College. We used to patronize it now and then, so when the Greek man who owned it fell off a ladder and wanted out quickly, he offered it to us. We bought it, and, lo, we were in the restaurant business.

Coffee houses featuring Flamenco music and dance were all the rage, so we climbed on the bandwagon and decided to give it a go. Our idea was to feature chess games, Neapolitan coffee, and desserts. I christened our cafe the Nine Muses, decorated the walls with artwork from local artists, hired a Flamenco guitarist to play in the evenings, and showed documentary films on Sunday afternoons. I put my ‘ud on display. We awaited the college crowd from the City College.

Trouble was, that people would come in, order a pot of coffee, play chess, and not move for hours. There was no customer turnover. We were not even making our rent. Within a month we decided to try lunch for the people who worked in the neighborhood. We even learned how to grill hamburgers. Soooo many hamburgers, but no profit. We would try dinners.

Dinner seemed to be what the customers wanted. Without any experience, we did it all: shopped, prepared, and cleaned; I became the chief cook. Within three months the business began to take shape. Customers wanted home-cooked meals, and I soon became the “mother” of the college crowd. Word of our new offering traveled faster than we were prepared for—so much so that in three months, at the height of the dinner hour, I fainted amidst hungry customers and the kitchen came to an abrupt halt. I had forgotten to eat that day; Satya and I couldn’t keep up with the demands of running a restaurant. Business was on the rise so we decided to hire some help.

Not wanting to hire a stranger, Jamila asked her friend Danny Reserva if he could recommend a potential employee. Danny responded immediately that one of his students, Bob Mackie, needed work.

Bob and his wife, Marianne, were high school sweethearts, and Marianne had just given birth to their first child. Bob came to work for Jamila after school each day, and soon he and Jamila were exchanging life stories, she about her belly dancing and Bob about his design studies and ideas.⁴

In Bob Mackie, Jamila found a friend with whom she connected creatively; she felt that he understood her.

He ate at the restaurant. When he was hungry, I fed him. When he wasn’t hungry, I force-fed him. You know, it’s that Mediterranean thing: food is love.

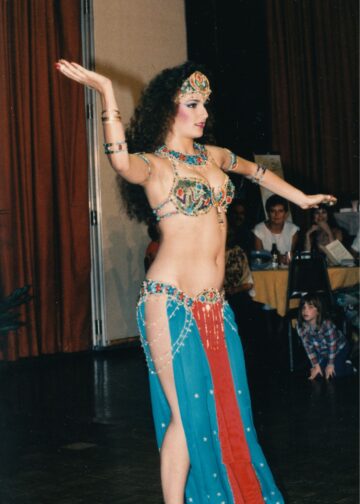

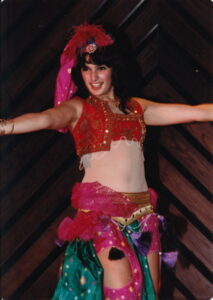

Marianne struggled to lose the weight she gained while pregnant, and Bob suggested she take up belly dancing if Jamila would agree to teach her.

There were no belly dance schools, and it was still considered improper. Marianne, however, was all for learning it, so I agreed to teach her during my off time.

Marianne was a natural. Who would have thought this American girl would have such incredible rhythm and a natural reaction to Middle Eastern music? She learned all the phases of the dance, played dynamite finger cymbals, and did a mean coin belt shimmy solo. She wowed her audiences, which later included Ravi Shankar, who shook his head in disbelief during her entire dance at the Greek Village in Hollywood. (By this time, the Greek Village was hiring belly dancers to perform regularly, including Marianne.)

Bob and I had many creative adventures. We bought our first piece of assuit together on Olivera Street, which he made into a dress for me. Bob designed unique costumes for Marianne’s dance and also designed smashing clothes for her to wear in between shows. He even did her hair. Bob recruited his school buddies who pooled their campy creativity together, and had Marianne pose as Theda Bara and many of the old time odalisques.

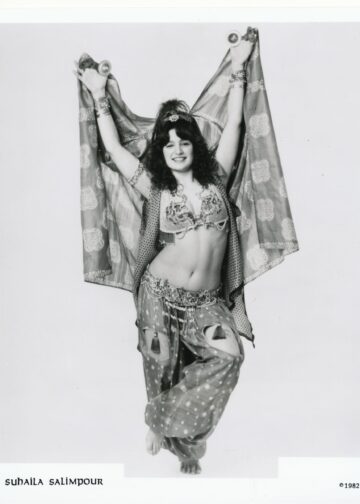

Jamila was meticulous about her costuming. She collected the best of materials. From her training at Renoir, she handcrafted coin body jewelry. She also consulted and worked with professional costume makers and seamstresses to create works of art that still allowed a dancer to move. Some of the most enduring examples are:

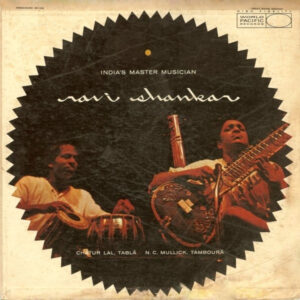

In 1957, Ravi Shankar (1920-2012), the famous Indian sitar player and composer, came to the United States with two other musicians: Chatur Lal, an Indian tabla player, and Nodu Mullick, a tamboura player. Their tour began with a large concert on the East Coast, but the trio also traveled throughout the country giving smaller concerts.

When the musicians came to the West Coast, Satya and Jamila helped find housing for the two in advance of their visit, as Satya was friends with Uday Shankar,⁵ Ravi Shankar’s older brother. The visiting musicians gave several performances including a concert at the University of California, Los Angeles. Jamila also attended a recording session with the trio with Richard Bock of World Pacific Records.

Chatur Lal became the focus of this early tour, and he often got top billing. Many Americans did not know what to make of Ravi’s lengthy improvised pieces; a review in Time magazine described American audiences as “receptive but occasionally puzzled.” In contrast, Chatur Lal received encores and standing ovations. Jamila quoted Ravi as repeatedly saying, “This is a percussion country,” and he felt his own work was not well received.

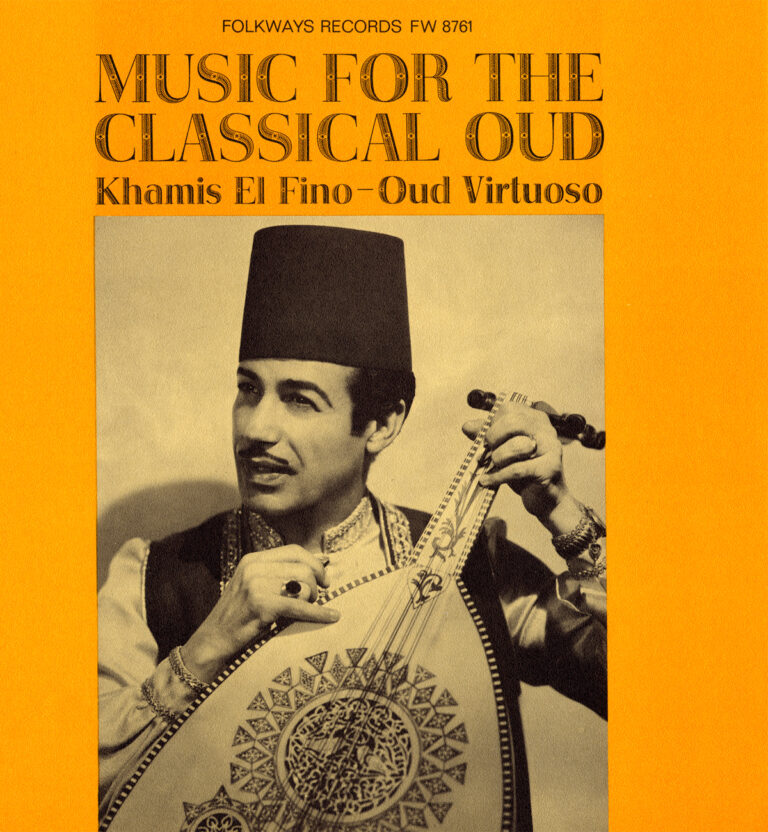

In 1959, Jamila met Lou Shelby and Khamis El Fino when the two men came to the Nine Muses for dinner one day. The men noticed Jamila’s ‘ud on display and asked to buy it. Jamila told them it wasn’t for sale. They explained that Lou was opening a new nightclub, the Fez, in Hollywood that would feature live music and belly dancing. Jamila let El Fino borrow the ‘ud for the opening night, and she eventually allowed him to purchase it from her.

Jamila and Satya were invited to and attended the opening night of the Fez, and it was obvious that Satya was more than enchanted by the dancer that night. Jamila saw him look at this woman in a way he had not looked at in her in a long time. At the start of their marriage, Satya had insisted Jamila quit dancing and now, according to Jamila, he “gaped with his mouth open in admiration” at another belly dancer. Satya enthusiastically began talking about hiring a belly dancer for the Nine Muses or maybe opening a nightclub that featured belly dance. In the meantime, Satya and Jamila began making plans to visit India.

We went to the Indian Consulate in San Francisco and, having gotten the passport business over with, we decided to go sightseeing in the city. We ended up in North Beach, which, at that time, was the stomping ground of the poets (the beatniks). Jack Kerouac’s On the Road began a trend of cross-country hikers. As we were walking down Broadway Street, which was dotted with Italian grocery stores, we passed a burlesque club called the Pink Elephant, which was where the Casbah Arabic nightclub now stands. As we looked at the photos of the girls in the show, we saw Claresa as the featured dancer dressed in an Oriental dance costume. I had seen Claresa some time back when she came to visit me at the Nine Muses; I knew she had been securing dance jobs and also had a new non-Armenian boyfriend.

We decided to see her perform. I remember thinking that although it was admirable for her to present a straight ethnic dance in a club that featured burlesque, by appearing in such an establishment people would associate the dance with burlesque or stripping. She saw me and spoke with me after her performance. She was unable to get hired at the Fez in Los Angeles because they initially brought talent straight over from the old country.

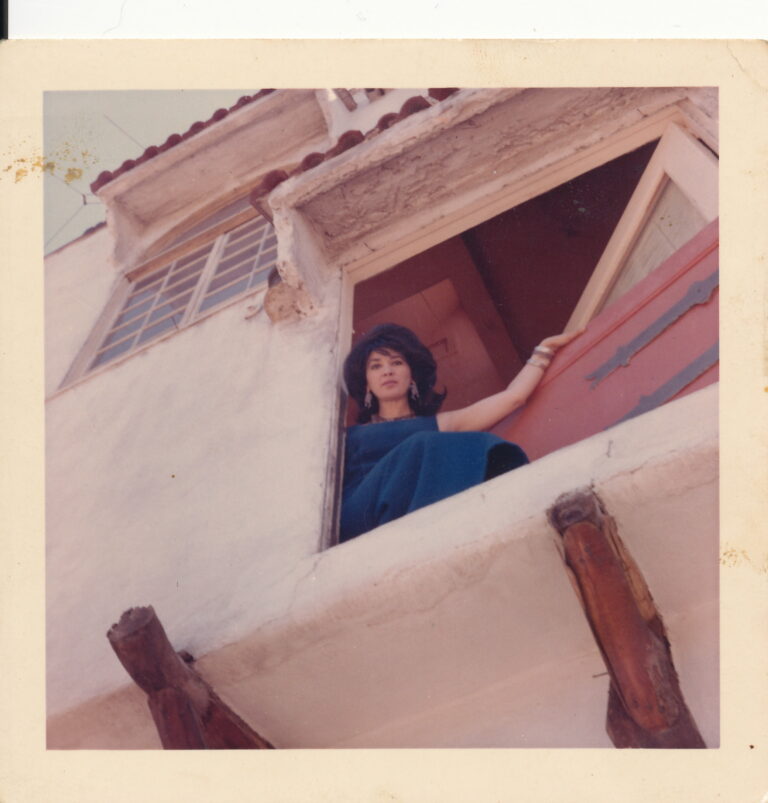

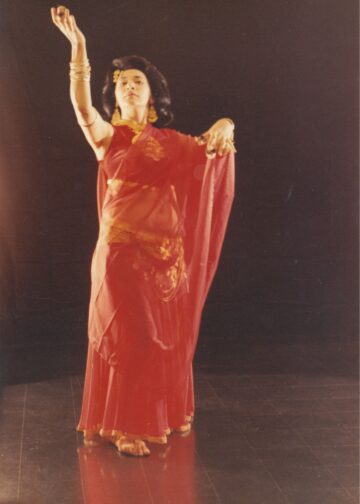

As Satya and Jamila continued preparing for their upcoming trip to India, Jamila realized that she did not want to go to India with Satya given the existing problems in their relationship. Satya left for India alone, and Jamila was now able to return to her dancing career.⁶

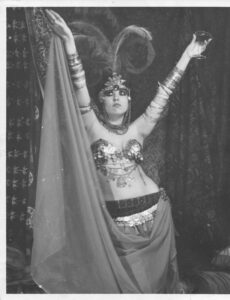

I commuted to an Armenian club in Fresno, where Richard Hagopian played for me, and I danced at the Greek Village, which was now under new ownership. In 1959, I danced and had student nights upstairs in Sinbad’s Lounge at the Fez.⁷

And then Khamis El Fino came to work at the Fez, inspiring every dancer he played for with his virtuosity on the ‘ud; an ‘ud, which incidentally had belonged to me. I had sold it to Khamis. For those of us who preferred Egyptian-style dance, his knowledge of current Egyptian music was refreshing. Since the Fez was primarily a dinner house with a show and intermissions, audience participation would have been disruptive to the continuity of the show. And so, Sinbad’s Lounge, featuring almost continuous music by Khamis, became our favorite hangout, and also the latest phenomenon. A large influx of Arab students from countries such as Algeria, Tunisia, Egypt, and Iraq attending schools in Los Angeles also came to see Khamis play. We thought it was perfection to dance for an appreciative audience who sang and clapped along as we performed. We wore out Khamis with our enthusiasm. Because so many of my dance students wanted to perform, we set a time limit on performance length to accommodate more dancers—a format I later used in my festivals. Students who became familiar with Khamis’ repertoire could request a specific musical [song]. It was the first time that a musician of his caliber was available to accompany an amateur dancer. We could count on events like this one for quite some time.

Around this time, Jamila began dating a new man. Jamila actively made jewelry and costumes for herself and her students as she revived her dance career. However, her new boyfriend’s patronizing comments about how cute she was when she played with her little coins irritated her. Not surprisingly, Jamila did not date the man for very long.

I begged Lou Shelby, owner of the Fez, to have me dance in his show downstairs, perform a show upstairs, teach Oriental dance at the Fez (thereby insuring a steady supply of dancers who were very hard to come by), and hostess for him in the evening. I quoted for him what I thought was a reasonable salary, knowing it would augmented by my income for teaching. Louis said he would think about it; I think he was reluctant to let me dance as I was over 30, and many considered that too old to be a dancer.

In the meantime, the Oriental dance movement had come to San Francisco and was booming. Marianne Mackie, now working full time at the Greek Village, was so much in demand that 12 Adler Place in San Francisco called her to dance at a very attractive salary, and she decided to go. Marianne promised to make me proud.

Marianne was successful and generated a lot of business for 12 Adler Place. It’s hard for any dancer to leave her home, pay two rents, and make new friends; Marianne quickly wanted to return to southern California. But in less than a year, Marianne left San Francisco to try her luck on Broadway in Manhattan. Her first love was musicals, and she had an agent who was ready to book her in New York. She had changed her name to Lulu Porter. I was unhappy that she would not be belly dancing anymore, but when I saw how hopeful she was about her new career, I was happy for her.

Meanwhile, I continued to teach and hold student nights at the Fez. When Marianne left San Francisco, 12 Adler Place’s management felt the only one who could replace Marianne and generate as much business as she did was her teacher. Yousef Kouyoumdjian, who was now working at 12 Adler Place, pleaded with me to move to San Francisco, and I felt pressure to move there. I wanted to stay in Los Angeles.

Everything seemed to happen at once, and my direction was uncertain. The money I was offered to dance at 12 Adler Place was too good to turn down, so I decided to escape to San Francisco with my “cute little coins.” At first, I stayed for just two weeks. The music was fantastic. The audiences were great. I never felt better.

When one dancer heard I was coming to San Francisco, she exclaimed, “Jamila is coming to dance? Oh, she teaches. Now she’s going to flood the market [with her students]!” As it turned out, we worked so hard that there was hardly any time to teach: three one-hour shows, six or seven nights a week.

12 Adler Place was a club in San Francisco in what was then mostly an Italian neighborhood called North Beach, San Francisco’s Little Italy. It was part of what was once the historic and notorious Barbary Coast,⁸ a seedy neighborhood known for gambling, prostitution, and crime. The neighborhood had been an actual beach that was landfilled at the turn of the 20th century. North Beach has long been a hub for those seeking alternative lifestyles, such as the bohemians in the 1900s, the beatniks in the 1950s and early 1960s, and the hippies in the late 1960s. It continues to serve as home to many of the strip clubs that opened in the 60s and 70s, such as the Condor Club and the Hungry, as well as long-standing Italian restaurants.

12 Adler Place itself has a sordid history. After the United States Government repealed the prohibition on selling or making alcoholic beverages in 1933, bars began reappearing all over San Francisco. In 1952, Tommy Vasu opened the first legal lesbian bar in San Francisco, which joined two existing properties: Tommy’s Place (on Broadway) and 12 Adler Place. Police raided Vasu’s clubs in 1954, because, even though her bars were legal, she ran an underground prostitution ring.⁹ The ensuing publicity brought about a very negative response from the public about homosexuality, which ultimately caused Tommy to close down her clubs soon thereafter. New ownership of the properties featured jazz and improvisational “beatnik-style” music.

Around 1961, the club began featuring Middle Eastern music led by Naji Alash (also known as Naji Baba) and belly dance performances. He previously created and led the Naji Baba Trio¹⁰ but left that group to focus on bringing Middle Eastern music to 12 Adler. Naji recruited Yousef Kouyoumdjian from the Fez and persuaded Marianne Mackie (now known as Lulu Porter), to be one of the first belly dancers in the club. Jamila soon followed. The area was focused on bringing in tourists and young soldiers stationed in the area. The sidewalks were full of people on the weekends, and there was quite a turnover in the crowds.

For a while, Jamila commuted back and forth between San Francisco and Los Angeles, maintaining apartments and performing in both cities.¹¹

On one of my frequent visits to Los Angeles, I called Bob Mackie. Marianne was still in New York pursuing a stage career, and Bob had moved out of their garret. He had rented a room somewhere in Los Angeles and invited me to visit with him; he had a surprise for me.

I expressed my sadness at how life had changed. We were all now separated. The Nine Muses was gone, my divorce was pending, Marianne and Bob were separated. What had I done? I thought maybe if I had never taught Marianne to dance things might not have turned out as they had.

Bob cheered me up. It was all right, he said. He might be getting a job as an assistant to Ray Aghayan, who was the designer for the Judy Garland Show.¹² Then he showed me his surprise. He had drawn a huge poster of me, very flattering, with a coin costume, face, and figure to die for. I carried it with me from club to club, wherever I worked.

The content from this post is excerpted from The Salimpour School of Belly Dance Compendium. Volume 1: Beyond Jamila’s Articles. published by Suhaila International in 2015. This Compendium is an introduction to several topics raised in Jamila’s Article Book.

If you would like to make a citation for this article, we suggest the following format: Totten, V. (2023). Salimpour Story. Jamila Marries Again. Salimpour School. Retrieved insert retrieval date, from https://suhaila.com/the-salimpour-story-jamila-marries-again

¹ Robert Gary (1920-2010) was a script supervisor for the Fame television show, which is how Suhaila learned about the audition for a cast dancer on that show. She performed on the show for one season following her high school graduation. He was also Jamila’s escort at Suhaila’s wedding to Andre Khoury.

² The Chouinard Art Institute was founded by Mrs. Nelbert Murphy Chouinard in 1921. In 1961, Walt Disney founded the California Institute of the Arts, which was created by a merger of the Chouinard Art Institute and the Los Angeles Conservatory of Music.

³ To make extra money, Bob Mackie created designs and sold them for $20 each to top designers to use as their own.

⁴ Uday Shankar (1900-1977) was a professional Indian dancer and choreographer who fused elements of Indian classical, folk, and tribal dance with Western theatrical technique and helped popularize Indian dance around the world.

⁵ Satya’s father in India needed money, so the couple sold the Nine Muses prior to Satya leaving for India. The new owner paid half the money to seal the transaction, and Satya took that portion to India. The rest was paid out to Jamila in regular installments over a few years. Jamila also trained the new owner on how to cook the dishes and run the business.

⁶ Moustapha Akkad (1930-2005) was a young film student from Syria who frequented the clubs in which Jamila danced. He became a friend of the family and later watched Suhaila perform regularly when she moved to Los Angeles after graduating high school in 1985. Akkad produced The Message and Lion of the Desert starring Anthony Quinn as well as eight Halloween movies.

⁷ Through the 19th century, Europeans used the term “Barbary Coast” for the North African coastal region (now Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya), homeland of the Berbers. The African Barbary Coast was often associated with pirates who preyed on European ships. For a time, San Francisco was also referred to as the Barbary Coast, and reached the height of its notoriety during the California Gold Rush (1848-1858).

⁸ Max Tilke, Oriental Costumes and Their Designs and Colors (Berlin: E. Wasmuth, 1922).

⁹ Nan Alamilla Boyd, Wide-Open Town: A History of Queer San Francisco to 1965 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003), 88.

¹⁰ The Naji Baba Trio performed improvisational music at the Cellar on 576 Green in North Beach; the Cellar was a famous Beatnik club known for poetry reading and jazz music. The trio also performed at the Vagabond on 800 Larkin in the Tenderloin District of San Francisco.

¹¹ Jamila’s long-term friend, Bob Gary, owned the Jack London House, which was comprised of several flats. When Jamila was still traveling back and forth between Los Angeles and San Francisco, she lived in one of the Gary’s apartments when she was visiting Los Angeles.

¹² Bob Mackie did get the job with Ray Aghayan and went on to design iconic gowns and costumes for The Sonny and Cher Comedy Hour (later followed by the Cher variety show and The Sonny and Cher Show). Bob and Ray were partners, business and personal, for nearly 50 years until Ray passed away in 2011.