The Ballets Russes, considered one of the most innovative dance companies of the 20th century, was an itinerant ballet company based in Paris that performed between 1909 and 1929 throughout Europe and on tours to North and South America. Despite its name, the company never performed in Russia, and (after its initial Paris season) had no formal ties there.

For the purposes of this study guide, we are not only interested in the history of the company, but also how it affected both Modern and Oriental dance, as well as how it shaped European and American views of the Middle East. Choreographer and dance scholar Laurel Victoria Gray claims that its depictions of forbidden harems and seductive temptresses in the so-called “Oriental Ballets”—Schéhérazade, Cléopâtre, Thamar, Le Dieu Bleu, Les Orientales, and the Polovestian Dances from Prince Igor—helped the Ballets Russes become one of the more “notable and successful exporter[s] of pseudo-oriental dance.” The dances, according to Gray, “depicted a wild and erotic East—passionate, sensuous, and violent.” The Oriental ballets themselves created “waves of Orientalism throughout the world of fashion and art” in Paris between 1909 and 1912, leaving a lasting impression on the Western imagination.¹

Founded in 1909 by Russian impresario Serge Diaghilev (1872–1929), the Ballets Russes blended Russian and Western European traditions with sometimes shocking and scandalous modernism through its powerful combination of music, choreography, and set and costume design. Diaghilev commissioned ballet scores from innovative composers such as Igor Stravinsky, Sergei Prokofiev, and Erik Satie; the company featured and premiered works by groundbreaking choreographers Michel Fokine, Vaslav Nijinsky, and the young George Balanchine. In addition, such influential artists as Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, and Coco Chanel were also involved in the company’s artistic development.

The Ballets Russes pushed the boundaries of ballet technically, artistically, and physically, leaving an impact on dancers in all genres.

One of the company’s great choreographers, Michel Fokine—who worked with the Ballets Russes between 1909 and 1912—eschewed what he believed to be pedantic and sterile presentations of movement and storytelling in ballet at the time, which included stilted miming and costumes that harkened back to the dance’s Baroque beginnings. He rejected formal classical ballets like The Sleeping Beauty and Swan Lake, favoring instead three or four short contrasted works rather than a full evening’s performance. He felt that dancing should be a truly expressive medium and not only a demonstration of technique, and that the type of movement, music, and design should reflect the time and place of the subject of the choreography.²

In Fokine’s ballets, the theme dictated the style of the entire presentation, and the steps given meaning and emotion. Fokine also took female dancers out of their pointe shoes to dance in slippers, and choreographed whole dances intended to be performed barefoot, which was quite controversial, because at the time, proper dancers always wore tights and slippers. In addition, the corps de ballet became an integral part of the ballet instead of just a decorative background.³ He also drew from folk dance traditions of the Caucasus for his dances, placing long veils on the heads of female dancers in the Polovestian Dances.⁴ This new approach to ballet became the rage in Paris.

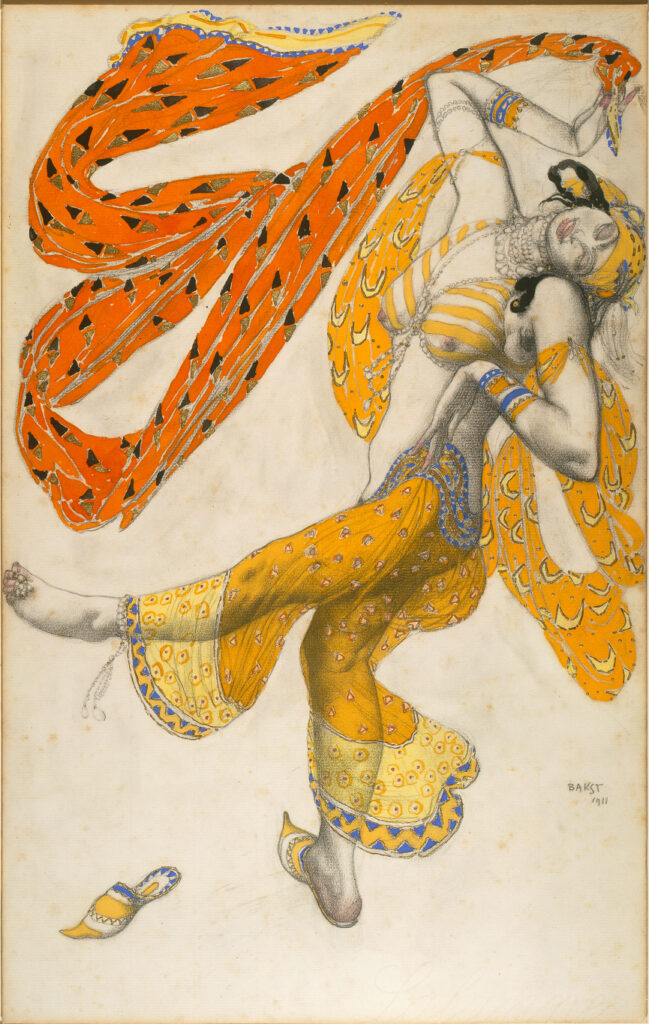

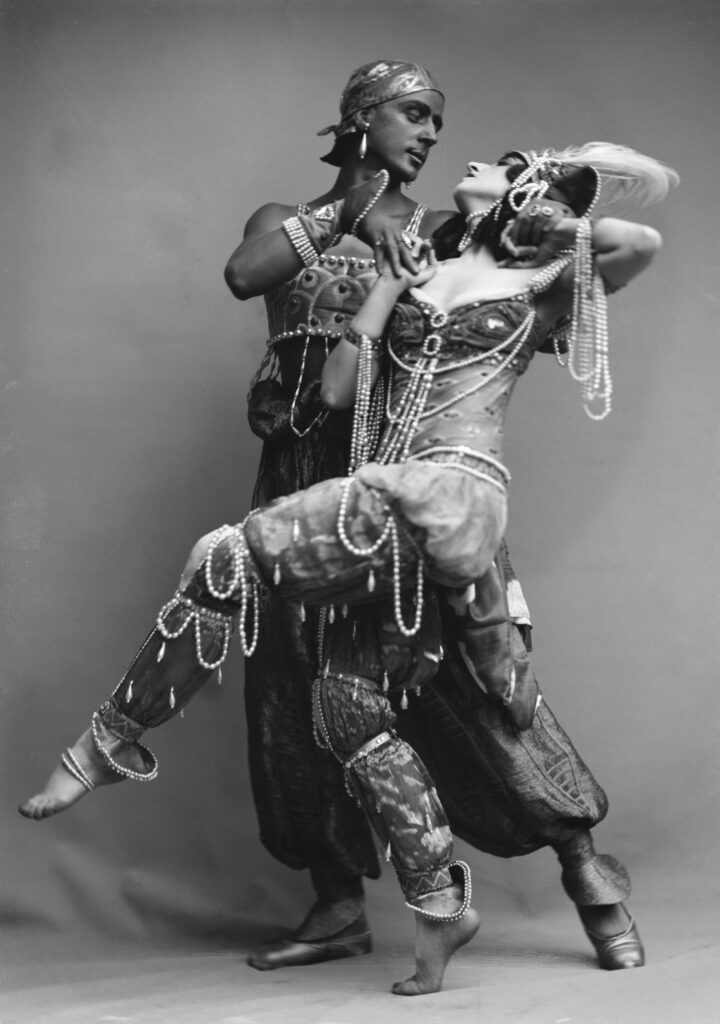

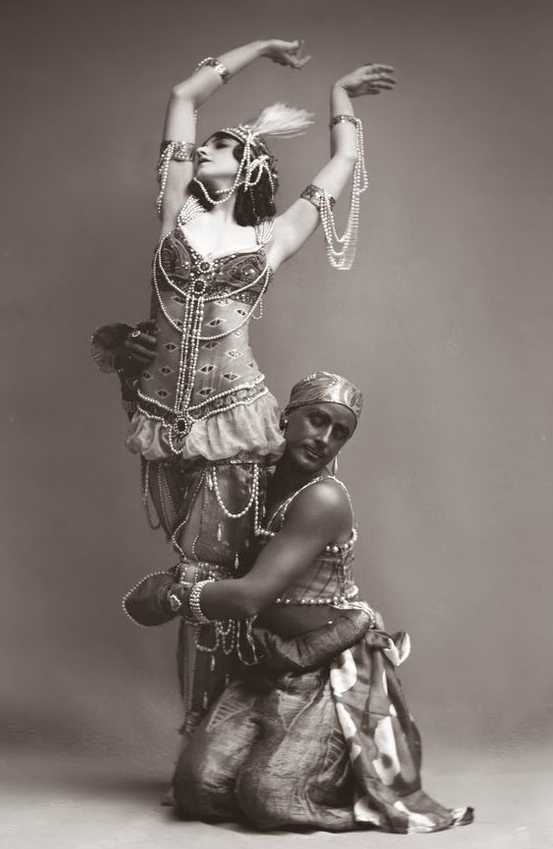

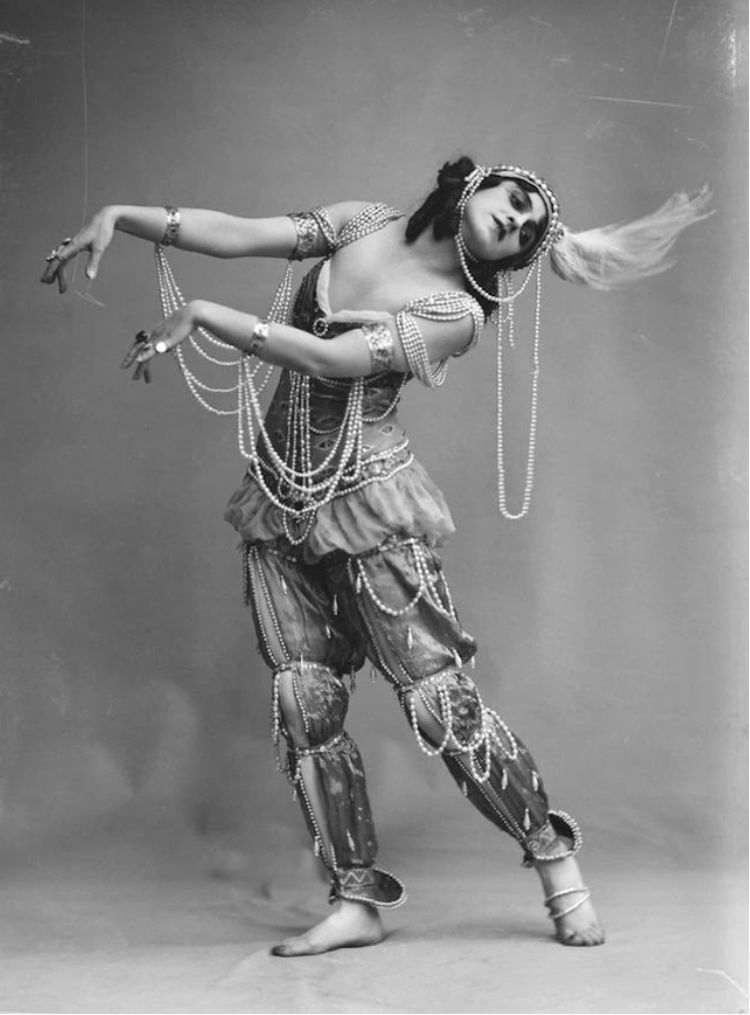

Also in 1909, the Ballets Russes hired Leon Bakst, a Russian painter and art teacher (Marc Chagall was one of his students). He worked first as a set designer, then later as a costume designer. He is known primarily for his lush, colorful, and sensual costuming which drew influence from the Middle East, Russia, and Central Asia. Bakst’s vivid, expressive, and fluid designs reflected and inspired Fokine’s vision of a modern ballet. Bakst’s costume design drew from broad-brush Oriental themes, such as “harem pants and a nearly bare upper torso, covered only by strategically placed, pearl encrusted hemispheres.”⁵ His decadent and boldly colorful set and costume design for Fokine’s ballet Schéhérazade (1910), created a sensation, as did Fokine’s inclusion of an orgy scene of the Shah’s wives with the slaves,⁶ an event that never happened in the original One Thousand and One Nights.

Also in 1909, Ida Rubinstein (1885-1960), a wealthy Russian Jew with little-to-no ballet training, made her debut as the title role in the Ballets Russes Cléopâtre.⁷ Both Fokine and Bakst recommended her for the part, and Diaghilev himself was impressed with her stage presence.⁸ Captivated by her dark features and tall, angular body, Bakst said that the Ballets Russes was “blessed” to have her.⁹ Michel Fokine, too, took a great interest in her, which was highly unusual as a choreographer of his stature would rarely invest much time and effort in a performer who had no training as a child.¹⁰ Rubinstein also played Zobeida in Schéhérazade, in which her character dies from a self-inflicted wound as “atonement for her unleashed sexuality.”¹¹ She performed barefoot and brought the femme fatale image to the high art of the new ballet presented by Diaghilev.

The Ballets Russes also featured dancer and choreographer Vaslav Nijinsky (1889-1950), who was trained in the Russian Imperial Ballet. He was an instant success on the Parisian stage from the Ballets Russes’ first season in 1909. Audiences had not seen an equivalent male dancer for more than two decades, because before the Ballets Russes, male dancers had been stripped of their power and relegated to minor roles. Nijinsky and Diaghilev began an intense relationship in late 1908, which ended suddenly when Nijinsky married (someone else) and Diaghilev dismissed him from the company in 1913.

After Fokine quit the Ballets Russes in 1909 (supposedly out of jealousy over Nijinsky and Diaghilev’s relationship), Nijinsky took over the role of lead choreographer for the company. His first choreography, L’après-midi d’un faune (The Afternoon of a Faun, 1912) to the score of the same name by French composer Claude Debussy, debuted in Paris in 1912. Bakst designed both the sets and the costumes; the choreography itself is often considered to be the first truly modern ballet. The performance, with its erotic subtext and suggestive movements, was also the first ballet in decades to feature a strong male lead, making it controversial and groundbreaking.

In 1913, perhaps Nijinsky’s most famous work, Le Sacre du Printemps (The Rite of Spring, to the score of the same name by Igor Stravinsky) went even further, as the choreographer moved towards more primitive, jerky movements and sharp body angles that reflected Stravinsky’s extremely rhythmic and avant-garde score. As with The Afternoon of a Faun, the dance included sexual themes, inspired by mythologized Russian fertility rites, which included human sacrifice. The first presentation of the ballet created such a stir that a now-famous riot broke out in the audience, which could only be stopped by the eventual arrival of the police.¹²

Bakst’s sets and costumes, along with the fantastical Oriental ballets of the Ballets Russes have had a profound impact on how the West perceives the Middle East and those who live there as well as Oriental dance itself. Although the company was based in Paris, many of the composers Diaghilev commissioned were, indeed, Russian. Dancer and scholar Laurel Victoria Gray argues that Russia’s geographical proximity gave the Russians long-term exposure to Eastern peoples, and the Russian composers and choreographers in the company “could use their first-hand knowledge of the regions they described to provide authentic detail.”¹³ The ballets were far from authentic; they were never meant to be accurate representations of true Middle Eastern dance or people. Gray says that the costumes and Oriental imagery presented in the Ballets Russes have had such an influence that it is “nearly impossible to dislodge the Russian Orientalist vision of the East from the popular imagination,” so much so that today, “audiences […] insist that the ‘authentic’ Oriental dance presentations must include veil dancing by girls in harem pants.” ¹⁴ Moroccan feminist Fatema Mernissi says, “Nijinsky’s ballet also influenced Hollywood to overemphasize the purely sexual dimension of Oriental dance,”¹⁵ a perception that Western belly dancers face even today.

Bakst’s designs for the Ballets Russes, in addition to the groundbreaking choreographies and movements, inspired not only a new generation of dancers, but the wider world of the arts. The company’s revolutionary ballets filtered through to theater, fashion, and daily life, including interior design and advertising. In the ballet world, the repertoire of the Ballets Russes remains an invaluable resource for choreographers today; over 200 different versions of The Rite of Spring have been choreographed since Diaghilev commissioned it.¹⁶ The Ballets Russes continue to inspire the worlds of art, theatre, music, and dance.¹⁷

The content from this post is excerpted from The Salimpour School of Belly Dance Compendium. Volume 1: Beyond Jamila’s Articles. published by Suhaila International in 2015. This Compendium is an introduction to several topics raised in Jamila’s Article Book.

If you would like to make a citation for this article, we suggest the following format: Keyes, A. (2023). The Ballets Russes. Salimpour School. Retrieved insert retrieval date, from https://suhaila.com/the-ballets-russes

1 Laurel Victoria Gray, “Envisioning the East, Russian Orientalism and the Ballet Russe,” Habibi, February 2002, accessed November 11, 2013, http://thebestofhabibi.com/vol-19-no-1-feb-2002/russian-orientalism/.

2 “The 20th-Century Ballet Revolution,” Victoria and Albert Museum, accessed December 12, 2013, http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/0-9/20th-century-ballet-revolution/.

3 Ibid.

4 Gray, “Envisioning.”

5 Ibid.

6 “The 20th-Century Ballet Revolution.”

7 Toni Bentley, Sisters of Salome, (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2002), 131.

8 Caddy, “Variations,” 45.

9 Bentley, Sisters of Salome, 136.

10 Ibid., 139.

11 Ibid., 142.

12 “Dance,” Ballets Russe Cultural Partnership, accessed December 12, 2013, http://www.ballets-russes.com/dance.html.

13 Gray, “Envisioning.”

14 Ibid.

15 Mernissi, Scheherezade Goes West, 69.

16 Notable choreographers who have also tackled Stravinski’s challenging score include modern dance pioneer Martha Graham, tanztheater innovator Pina Bausch, and postmodern dancer Molissa Fenley (who performs her Rite as an extremely athletic 34-minute long solo). The original Nijinsky choreography, once thought lost to time, was reconstructed by the Joffrey Ballet in the 1980s after meticulous research. As of the publishing of this volume, both Schehérézade (Kirov Ballet, 2002) and The Rite of Spring (Joffrey Ballet, 1987) are viewable on YouTube at http://youtu.be/CpE_pCHVBR4 and http://youtu.be/ewOBXph0hP4, respectively.

17 “The 20th-Century Ballet Revolution.”