- A History of Middle Eastern Music

- Genres of Music and the Ensembles that Perform Them

- The Great Four of Arabic Music

- Western and Middle Eastern Music Theory

- Introduction to Western Notation

- Middle Eastern Rhythms

- Middle Eastern and North African Instruments

In this section, we will study the varieties of rhythm found in Middle Eastern music. There are two types of rhythm found in Middle Eastern repertoires: “free” rhythm, and rhythmic modes. These modes are not to be confused with melodic modes or maqām; rather, they refer to repeating beat patterns, which are named and which form the basic structure of the piece.

Free Middle Eastern Rhythms

Free rhythm pieces are generally played by instrumental soloists and allow for the purest expression of the maqām, since they are not bound by set repeating rhythmic patterns, and the performer can concentrate exclusively on the emotional expression of the maqām they are playing.

These pieces are improvised by the musicians, and such a piece is frequently known as a taqsīm (pl. taqāsīm, Turkish taskim). Some taqāsīm do have rhythmic components, but it is common for such a free-rhythm improvisation to begin a set or suite of pieces. A taqsīm begins in a specific maqām, and while it may stray away from it into another maqām, it will always return to the original mode by the ending of the improvisation.

Middle Eastern Rhythmic Modes

Pieces with rhythm, by contrast, can be played by soloists or by groups. Most commonly, percussion instruments are involved, to set the pattern. A skilled percussionist will begin with the pattern, but may add any number of variations to it, ornaments, fills, extra drum hits, and other embellishments, to provide color and variation. In Arabic, this rhythmic pattern is known as a wazn (plural awzān, also called darb, and usul in Turkish), and it “consists of a regularly recurring sequence of two or more time segments. Each time segment is made up of at least two beats […] which can be long or short, accented or less accented.”¹ More traditionally, these patterns have been known as iqaāt (singular ‘iqa), or “rhythm.”²

There are more than 100 such patterns in use in both Arabic and Turkish music, some of which can reach incredibly long durations. These are difficult to identify except by the most educated specialists. Fortunately, most patterns are considerably shorter, often no longer than a single measure in Western notation. Most rhythms in music used by belly dancers fall into this category.

Accents in Middle Eastern Rhythms

An important element of these patterns is learning where to place accents. Different types of drum hits feature at different points in the pattern. The two most common hits are known as the “dum” (or “doum”) and the “tek” (or “tak”).

The doum is a loud sound made by striking the drum head (with the hand or a stick, depending on the type of drum) closer to its center to produce a heavy sound. The tek, by contrast, is a thinner and sharper tone, made by striking closer to the rim of a given drum.

A third sound, the “ka,” represents the same thinner sound, played in alternation with the tek. This would be the case, for example, when playing a drum with both hands in alternation: tek ka tek ka tek ka and so on. These sounds, used in various combinations, make up the basic Middle Eastern rhythmic patterns. Additional sounds and hits are added by drummers to give a greater variety and color to the overall percussion sound.

Common Middle Eastern Rhythmic Modes for Belly Dancing

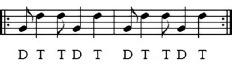

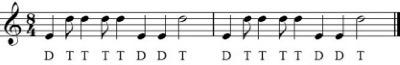

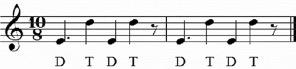

We will look at the most common rhythmic mode used for belly dancing, a pattern that has three different versions of the same basic rhythmic mode, depending on where one places the drum accents: maqsum, masmudi saghir (commonly known as baladi), and Sa‘idi. In each example, the lower and upper notes represent the doum and the tek respectively, simply to show how the beats contrast.

You do not need to think of them as actual tones. You may notice that the rhythm is in 4/4 in all three cases, but that the pattern is its own unique entity. It has become standard practice since the 20th century to notate these rhythms in Western musical notation, a useful method of displaying them, but one that does not fully define the rhythmic modes as they are conceived in Arabic theory.³

Maqsum

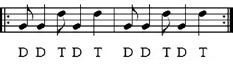

Figure 1: Maqsum

This rhythm is quite common in folk, classical, popular, and dance music; it is often used interchangeably with masmudi saghir and sa‘idi.

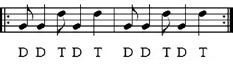

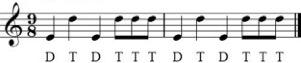

Masmudi Saghir

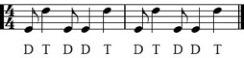

Figure 2: Masmudi Saghir (Baladi)

Considered perhaps to be the most well-known rhythmic mode, it is found in folk, classical, popular, and dance music. Its name translates to “small masmudi,” as it is similar in structure to the masmudi kabir, or “big masmudi.”

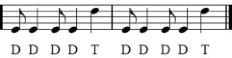

Sa‘idi

Figure 2: Masmudi Saghir (Baladi)

Considered perhaps to be the most well-known rhythmic mode, it is found in folk, classical, popular, and dance music. Its name translates to “small masmudi,” as it is similar in structure to the masmudi kabir, or “big masmudi.”

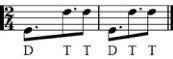

Figure 3: Sa‘idi I

Figure 4: Sa‘idi II

This mode is used primarily in Upper Egypt (the south), where it is also common to switch between it and the other two modes.

Additional Rhythms:

In the following section, we will break down popular and common rhythms found in music for dancing in rhythmic notation and add some cultural and historical context.

Rhythms in 2/4

Ayyub

Also known as “zar” or “zaar,” this rhythm is popular in entrances and exits, and is the rhythm most associated with trance dancing and other related rituals.

Figure 5: Ayyub

Fallahi

Often transliterated as “Fellahi,” this rhythm is named after the people of the countryside, farm-workers, and other rural residents. As such, it is popular in songs from the countryside, or baladi songs.

Figure 6: Fallahi

Malfuf

Also known as the leff (the triliteral Arabic root is the same: L-F-F, which roughly translates to “wrapped”), this rhythm is often used at the beginnings and endings of entrance songs. Musicians often play songs or sections of songs in this rhythm towards the end of a performance set as a cue for the dancer to make her final promenade before leaving the stage.

Figure 7: Malfuf

Khaliji

This rhythm is from the Arabian Peninsula, known as the khalīj in Arabic. It has a lilting quality, as well as some influences from the African continent, a result of the peninsula’s proximity to the Horn of Africa as well as African slaves brought to the region by Arab traders.

Figure 8: Khaliji

Karachi

As the name implies, this rhythm likely has South Asian and Pakistani roots.

Figure 9: Karachi

Rumba

Based on the latin rhythm of the same name, slow versions of this rhythm were popular in American Middle Eastern nightclubs for veilwork, floorwork, and performance with a sword. When played faster, its Latin American roots are clearer.

Figure 10: Rumba

Rhythms in 4/4

Balera (Bolero)

Named for the Latin dance of the same name, it was a popular rhythm for slow sections of sets in American Middle Eastern nightclubs.

Figure 11: Balera (Bolero)

Chobi (Iraqi Debke)

Often associated with Iraq, the Chobi is also an Assyrian folk dance. It is distinguishable from the more Levantine varieties of debke rhythms by the characteristic three “doums” at the beginning of the measure.

Figure 12: Chobi (Iraqi Debke)

Jerk

This rhythms has a rolling quality, and is often associated with Nubian music. It also has a similar feeling as a Samba rhythm (it’s sometimes called “Arabic Samba”), indicating its African roots. You can hear it in the opening section of Warda’s song “Fee Yom Wa Layla.”

Figure 13: Jerk

Nawari (or Nwari)

Although this rhythm sounds much like sa‘idi, be careful; it’s quite different because the first doum falls on the “&” after the 1. It is also from the Levant, particularly Lebanon, and is associated with Levantine debke songs, especially “Ya Ain Moulayatin.”

Figure 14: Nawari (or Nwari)

Wahda

“Wahda” translates to “one” in Arabic, because it features one doum sound. It is often used in the verse sections of long songs, particularly those of Umm Kulthum.

Figure 15: Wahda (or Waheda)

Zaffa

This rhythm is associated with the traditional Egyptian wedding procession—also called “zaffa”—often lead by a dancer.

Figure 16: Zaffa

Rhythms in 6/8

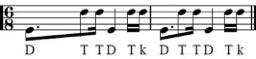

Debke 6/8

This rhythm is most associated with the debke, a line dance popular in the Levant, particularly in Lebanon.

Figure 17: Debke 6/8

Persian 6/8

Persian music is often in a rolling 6/8, showcasing the technique of the tombek player. You can hear this rhythm and variations of it in most Persian pop songs. It generally feels lighter than the Moroccan 6/8 in the same meter.

Figure 18: Persian 6/8

Sha‘abiyya/Shabia (Moroccan) 6/8

As the name implies, this rhythm is found in North Africa. It is polyrhythmic, in that it can be counted in small 6s or big 4s. It is also found in trance and other spiritual movement rituals. Note that the word “sha‘abi” means “popular” or “of the people.”

Figure 19: Sha’abiyya/Shabia (Moroccan) 6/8

Rhythms in 8/4

Masmudi Kabir

Masmudi kabir, or “big masmudi” is a longer rhythm often used for verse passages in longer songs. It can have two or three “doums” in the beginning. The Arabic root Ṣ-M-D, from which the term “masmudi” derives, means “to hold.”

Figure 20: Masmudi Kabir (two variations)

Chiftetelli

This rhythm appears in two variations, a slow one often used for veil work and verse sections of Arabic music, and a faster version found more often in Turkish and Greek music. The tstiftetelli (different spelling, same pronunciation) is a dance in Greece, done to the faster version of the rhythm. It means “double-stringed” in Turkish. The slower version of the rhythm was also a popular backing beat for taqāsīm in American Middle Eastern nightclubs.

Figure 21: Chiftetelli

Rhythms in 9/8: Focus on the Karshilama

The karshilama (Turkish karşılama), is a very popular folk dance, especially in Turkey and Greece. In Turkish, the word means “face to face greeting,” which marks it as being a communal folk dance; couples face one another when dancing. It is identifiable by a rhythmic pattern in nine beats, which give it its characteristic “staggering” feel at the end of each measure. It is sometimes known as aqṣāq in the Arab world, though this word refers to a different type of 9/8 rhythm in Turkey (where it is spelled “aksak”).

There are two common versions of the mode:

Figure 22: Karshilama

The second version of the mode is virtually identical, only omitting the final hit of each measure, either holding the second-to-last beat, or resting for the final beat. This form is popular with Romani musicians in Turkey. The nine-beat pattern remains the same:

Additional Rhythms

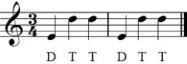

Valse (Waltz) 3/4

This rhythm is an imitation of the Western European waltz, and appears in many longer songs from the mid-20th century.

Figure 24: Valse (Waltz) 3/4

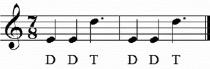

Laz 7/8

This rhythm is popular in the Balkans as well as the Black Sea region of Turkey. Count this compound rhythm as 1-2-1-2-1-2-3.

Figure 25: Laz 7/8

Sama‘i Thaqil 10/8

This rhythm is often most associated with the muwashshahat tradition, and is most often heard in the context of the song “Lamma Bada Yata Sama.” Choreographer Mahmoud Reda often used songs in sama‘i thaqil for his reconstructions and imaginings of what muwashshahat dance might have looked like.

Figure 26: Sama‘i Thaqil 10/8

Jurjuna 10/8

This rhythm is popular in Iraq and Iran, particularly in folkloric songs. It’s also found in Armenian songs. This rhythm is very similar to sama‘i thaqil, but is usually played faster.

Figure 27: Jurjuna 10/8

Sama‘i Zarafāt 13/8

Sometimes transliterated as “Sama‘i Dharafat,” or simply “Dharafat.” This rhythm is quite old, dating back to the muwashshahat tradition. It is prominently featured in the beginning of the Umm Kulthum song Al-Hubb Koullo, translated as “All the Love.”

Figure 28: Sama‘i Zarafāt 13/8

¹ Touma, Habib Hassan. The Music of the Arabs, translated by Laurie Schwarts. Portland, OR and Cambridge, UK: Amadeus Press, 1996, pp. 48.

² Marcus, Scott L. Music in Egypt: Experiencing Music, Expressing Culture. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006, pp. 60, / / Sawa, George Dimitri. Egyptian Music Appreciation. Toronto: Music Manufacturing Services, 2010, pp. 4., (for further explanations of iqā‘āt).

³ See Marcus, Music in Egypt, 61 and 69.

The content from this post is excerpted from Middle Eastern Music: History & Study Guide. A Salimpour School Learning Tool published by Suhaila International in 2018. This Music Book is an introduction to music concepts, history, and theory for belly dance.

If you would like to make a citation for this article, we suggest the following format: Keyes, A. and Rayborn, T. (2018). Rhythms. Salimpour School. Retrieved insert retrieval date, from https://suhaila.com/rhythms