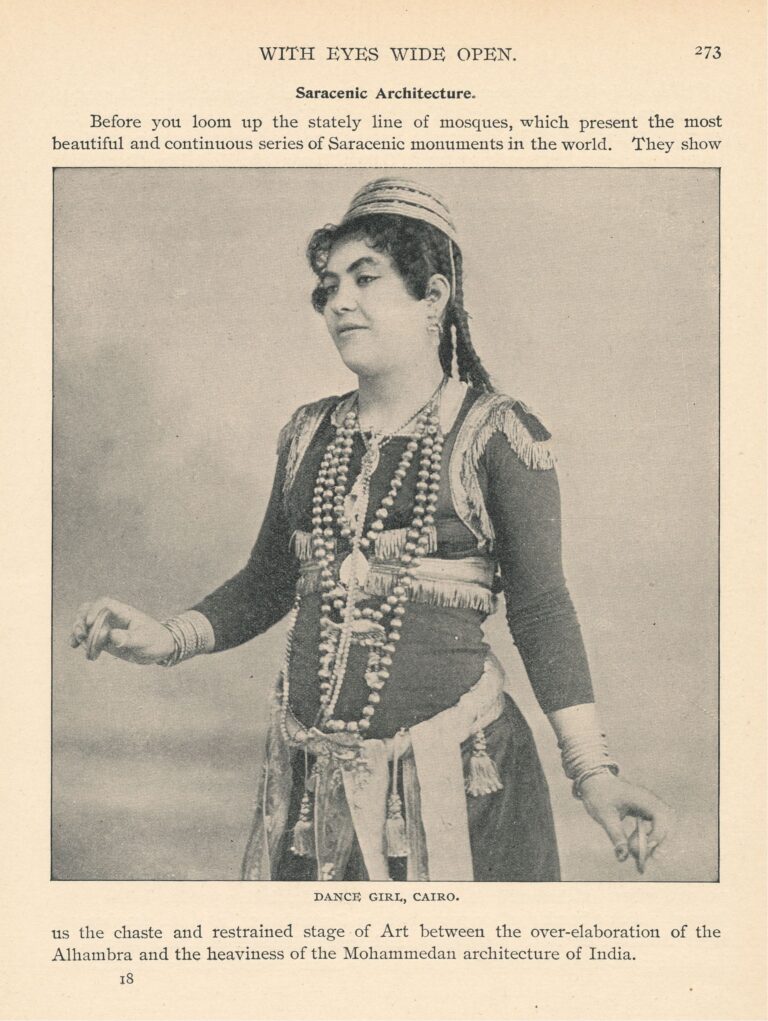

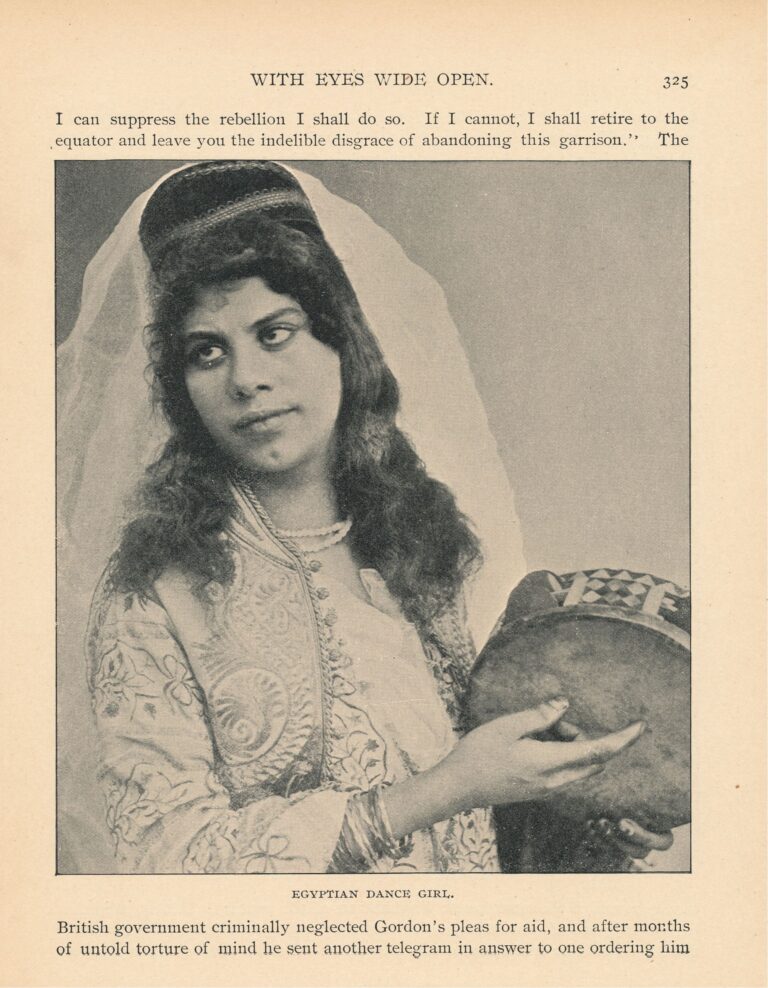

In general, female entertainers, specifically dancers, in the Middle East are perceived there as immoral, fallen, and without honor. Modern dancers perform and appear in public unveiled, as they have been doing since the early 20th century. They defy, according to Natalie Smolenski, “traditional standards of seclusion by performing unveiled for men, often without familial supervision, which harmed the reputation of female performers in general.”1 Dance scholar Najwa Adra says that dancers challenge the traditional values of “restraint, self control,” and “seriousness” that are “highly admired in women and men”² in Middle Eastern cultures.

To be a performer in the Middle East is to be stigmatized, especially if that performer is a woman. Dancers are at the bottom of respectability not only because they appear in public spaces unveiled, but because they use their bodies in order to make a living. As Jamila Salimpour tells us in her article “Customs, Conflicts, and Casualties,” her husband’s Persian family disapproved of both Jamila and her daughter Suhaila’s involvement in the dance; even nine years after Ardeshir Salimpour’s death, his family effectively disowned Suhaila for appearing on the cover of belly dance publication Habibi.³

Anthropologist and scholar Karin Van Nieuwkerk notes that only a few women working as performing artists—such as Umm Kulthum and Farida Fahmy—have escaped such moral stigma. For most female singers and dancers, however, prostitution is the measuring rod by which they are judged.⁴

Fitna

Why is dancing in public considered so dishonorable and disreputable? The answer lies somewhere in both culture and religion. Moroccan feminist Fatima Mernissi says that the reason for the separation and segregation of the sexes in North African and Middle Eastern society can be traced to the belief in fitna: the “social disorder that results when women sexually tempt men or engage in sexual relations with men other than their legal husbands.”⁵ Fitna—which can be translated from Arabic as “chaos,” but also as “a beautiful woman”—connotes the power women have to make men lose self-control⁶ and commit lewd acts against the teachings of the Abrahamic religions, especially those of Islam.⁷ Mernissi notes that women are believed to be endowed with a fatal attraction that erodes the male’s will to resist her and reduces him to a passive and acquiescent (i.e., feminine) role.⁸ She says that the “fear of succumbing to the temptation represented by women’s sexual attraction—a fear experienced by the Prophet [Muḥammad] himself—accounts for many of the defensive reactions to women by Muslim society.”⁹ Smolenski explains that when early Islamic scholars codified the concept of fitna, they “conceptualiz[ed] and nam[ed] a powerful phenomenon that must be controlled by religious, political and social forces.”¹⁰

Indeed, according to Mernissi, some Islamic religious authorities have likened women to have as much power as the devil. She notes that the 9th-century Islamic scholar Imam Muslim, an established voice of Muslim tradition, said that a woman “resembles Satan in his irresistible power over the individual.”¹¹ She also says that medieval Islamic theologian Imam Ghazali viewed civilization as “struggling to contain women’s destructive, all-absorbing power,” and that “women must be controlled to prevent men from being distracted from their social and religious duties.”¹² So, unlike Western Christianity, where sexuality is condemned except for procreation, in Islam broadly speaking, women themselves are the danger. Women, says Mernissi, are “the embodiment of destruction, the symbol of disorder […] the epitome of the uncontrollable, a living representative of the dangers of sexuality and its rampant disruptive potential.”¹³ She says that many Muslims believe that the “most potentially dangerous woman is one who has experienced sexual intercourse.”¹⁴ Therefore, in the Middle East, female entertainers in particular are believed to have the power to make use of fitna, using their feminine power to ensnare men, making them particularly “bad and immoral women.”¹⁵

For women, modesty, particularly in the public sphere, is what brings honor to self and family.¹⁶ The professional entertainer, particularly the women whose “public body” may be enjoyed by the masses, is paid for their service and this exchange is stained with dishonor. A woman in a traditionally male [i.e., public] space upsets God’s order, says Mernissi, by inciting men to commit zina (sexual relations outside of marriage), and if the woman is unveiled, such as in the case of a belly dancer, the situation is aggravated.¹⁷ In an interview with Shawna Helland, Ali Jomma—a man born in 1963 in rural Lebanon—said that “in Islam a woman is supposed to cover herself, with the exception of her face and her hands,” and that “a belly dancer is considered to be naked.”¹⁸

The nightclub—as opposed to performance circuits of theaters, five-star hotels, or even weddings and saint’s day celebrations—in particular is the subject of great contempt. When Van Nieuwkerk conducted her research on the public perception of dancers in Egypt, she found that “most people agreed that, especially for women, working in a nightclub is the worst.” She says that Egyptians perceive both singers and dancers in the nightclubs as “improper because they are hidden in disreputable places.” She also added that “some things that happen in nightclubs—mainly pertaining to money, alcohol, and sex—are not just shameful but entirely ḥarām, [prohibited or] taboo.” In addition, nightclub performers are perceived as extremely greedy.¹⁹ This perception is not limited to Egypt. When asked about nightclubs in the Middle East, Ali Jomma said that the ones that “feature belly dancing in Beirut are the equivalent to our strip joints here [Calgary, Canada] and from a moral, social and religious point of view, that’s how they are looked at,” and that the two are “the same kind of thing.”²⁰

Dancing for Money

Professional dancers are also maligned for using an activity done for fun as a means to make a living. Both men and women will dance in social celebrations such as weddings, but would most would never consider doing so for pay. Dancing at a family party or gathering in the private home or the courtyard of a home is permissible and up to the discretion of the participants. Some women choose to dance in these settings, while others do not. Dance in these contexts is permissible, because, as Najwa Adra says, the “social rules are relaxed at home and among friends,” and “one may behave as loosely or as decorously as one chooses. Belly dancing is considered, according to Adra, “frivolous” and for a woman to do it professionally is “not considered appropriate for those who are expected to maintain a restrained and respectable demeanor.”²¹

Because dance is considered “fun,” it is discounted as a possible “art.” It is not a reputable career choice by any means, because in the Arab world (as well as the wider Muslim-majority Middle East), professional dancers do in public what most people consider appropriate only in private.²² Natalie Smolenski says that this “democratic conception of song and dance […] has the effect of devaluing the skill involved in professional performance.”²³ Many people in the Middle East believe that because everyone does it, so it is not something for which one should receive payment. William C. Young notes that an Egyptian woman told him that “everyone knows how to do it [belly dance]! It doesn’t take any special training; we learn from our mothers! So it’s not ‘an art.’”²⁴ Smolenski elaborates on this interaction, commenting that in the eyes of Middle Eastern people, “there is little to distinguish a professional dancer from an amateur,” and the professional dancer “earns condemnation because of her perceived desire to profit from a very ordinary ability and to gain special acclaim from men.” She also says that “this logic, paid dancing resembles prostitution: because, in the popular imagination, any woman has the ability to deliver sexual pleasure to men, there is no cultural vocabulary for a ‘sexual artist.’”²⁵

Women who engage in dance for a living are also perceived, as Young notes, as “social failure[s].” By selling their performances (their bodies), they are, in essence, selling their honor and respectability.²⁶ Smolenski comments that people “may consider women who are not ‘properly’ secluded to be undervalued by their families or ‘floating’ without a social support network, and therefore suspicious or untrustworthy.”²⁷ Classism also reveals itself as a factor in the disdain against professional dancers. Adra notes that most Arabs will agree that dancing for pay is only permissible for professional dancers or others from low-status groups, and dancing for members of the opposite sex in a large public arena is not permitted.²⁸

Then, why has the dance persisted? If performing belly dance is so dishonorable, why are there still belly dancers? Despite the stigma, there continues to be a market for dancers, both domestically and from tourists. When scholar Karin Van Nieuwkerk interviewed an Egyptian tailor about his views of professional dancers and singers, he said that despite considering their jobs as “shameful […] detestable […] and ḥarām (taboo),” he said he does “like to watch it […] but the fault is theirs.”²⁹ In other interviews with Egyptian citizens, Van Nieuwkerk says that some people “acknowledged the positive aspects of singers and dancers at weddings,” and said that entertainers “enliven the party and bring a happy and merry atmosphere.”³⁰ Weddings, in contrast to nightclubs, according to Van Nieuwkerk, are “expressions of happiness connected to family occasions.”³¹ She also notes that performers on the “art circuit of theaters, conservatories, radio, and television,” as well as those who work in the nightclubs of five-star hotels are generally considered respectable, to a point.³² Anthony Shay says that another reason for the dance’s survival is that some are simply born into families of entertainers, and that is the profession espoused by their kin.³³

Archetypes and Images

Several scholars have observed that some performers have been able to escape much of the stigma associated with their profession by creating personas and characters for themselves that play on popular archetypes, nostalgia, and imagery. Smolenski says that these performers have been able to “manufacture respectability” by playing on these archetypes to “win great acclaim and respect.”³⁴ One common archetype that dancers employ is that of the bint al-balad, a “country” girl associated with authenticity and even a bit of innocence.³⁵ The bint al-balad describes a woman who is “strong, fearless, tough,” “feminine,” “cares for [her] appearance,” and is “coquettish.”³⁶ She also, as Van Nieuwkerk points out, “exhibits much of the ‘manly’ behavior necessary to endure in the entertainment business,” and she has social license to behave “willfully, loudly and even aggressively, especially when it comes to defending her sexual honour.”³⁷ The bint al-balad is not entirely without restriction, however; she must, as Smolenski says exhibit “modesty and religious devotion.”³⁸ Another role that dancers often emphasize is that of being wives and mothers, which Van Nieuwkerk says helps humanize them, showing that they are working for “the betterment of their families as opposed to personal glory or greed.”³⁹ z

Islamic Views on Dancing

Apart from fundamentalist interpretations of the Qur’an and Ḥadīth, most scholars agree that Islam does not explicitly prohibit dancing, but the issue is not settled.⁴⁰ Najwa Adra says “there is ongoing debate among Muslim religious scholars about the permissibility in Islam of dancing and playing musical instruments,” and that this discussion “extends throughout the Islamic world and is not limited to Arab societies.⁴¹ She says, as far as early Islamic edicts, there is “little evidence […] to support a complete ban on dancing.”⁴² As mentioned above, many people in the Middle East dance socially as an “important means of expressing joy and happiness in socially approved contexts such as weddings.”⁴³

That said, professional dancers have been the subject of increasing intimidation in the past four decades. After the Iranian revolution, Ayatollah Khomeini banned all forms of dance when the Islamic Republic was officially established in 1980 in response to what Shay believes to be “accumulated negative historical perceptions of dance and professional dancers.”⁴⁴ Also in the 1980s, Egypt created a sort of “belly dance inspection unit” that “polices venues to enforce the strict dress code introduced” as a means to placate a rising wave of religious conservativism. Part of this dress code prohibits “bare midriffs, cleavage, and revealing skirts;”⁴⁵ however, dancers who perform in higher-class and arts venues, such as theaters and five-star hotels could often escape these restrictions. Since 2000, political turmoil and pressure from religious groups have further contributed to waning interest in belly dance. Adra writes that “some religiously conservative families argue that music and dancing are immoral,” and would not hire belly dancers for their family weddings and celebrations. Instead, says Adra, “these families replace professional dancers and musicians with chanters of religious songs.”⁴⁶

The content from this post is excerpted from The Salimpour School of Belly Dance Compendium. Volume 1: Beyond Jamila’s Articles. published by Suhaila International in 2015. This Compendium is an introduction to several topics raised in Jamila’s Article Book.

If you would like to make a citation for this article, we suggest the following format: Keyes, A. (2023). Perception of Dancers in the Middle East. Salimpour School. Retrieved insert retrieval date, from https://suhaila.com/perception-of-dancers-in-the-middle-east

1 Smolenski, “Modes of Self-Representation,” 57.

2 Najwa Adra, “Belly Dance: An Urban Folk Genre,” in Belly Dance: Orientalism, Transnationalism & Harem Fantasy ed. Anthony Shay and Barbara Sellers-Young (Costa Mesa, California: 2005), 38.

3 Suhaila Salimpour, “Why We Dance,” Habibi 20:2 (2004): 21. The cover in question is on Habibi 8:9 (1985).

4 Van Nieuwkerk, “Changing Images,” 136.

5 Smolenski, “Modes of Self-Representation,” 54.

6 Mernissi, Beyond the Veil, 31.

7 An anecdote that illustrates this fear of feminine fitna is from journalist and author Geraldine Brooks, who was denied a hotel room in Saudi Arabia because she was traveling without a male guardian. After receiving special permission from the police to check in alone, she was given a room on a vacant floor. When she remarked to the non-Arab bellman that the hotel management must think she was dangerous, he replied, “They think all women are dangerous.” For more about Brooks’ personal experiences living and working as an unaccompanied woman in the Middle East see Nine Parts of Desire.

8 Ibid., 41.

9 Ibid., 54.

10 Smolenski, “Modes of Self-Representation,” 54.

11 Mernissi, Beyond the Veil, 42.

12 Ibid., 32.

13 Ibid., 44.

14 Ibid., 42.

15 Van Nieuwkerk, ‘A Trade Like Any Other’, 154.

16 Anne Rasmussen, “‘An Evening in the Orient’: The Middle Eastern Nightclub in America,” in Belly Dance: Orientalism, Transnationalism & Harem Fantasy ed. Anthony Shay and Barbara Sellers-Young (Costa Mesa, California: 2005), 200.

17 Fatema Mernissi, Beyond the Veil, 144.

18 Shawna Helland, “The Belly Dance: Ancient Ritual to Cabaret Performance,” in Moving History/Dancing Cultures: A Dance History Reader, ed. Ann Dils and Ann Cooper Albright (Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press, 2001), 132. Apart for the illuminating interview with Ali Jomma, this article contains some questionable scholarship in regards to the history of belly dance, and tends towards romanticizing it.

19 Van Nieuwkerk, ‘A Trade Like Any Other’, 122-4.

20 Shawna Helland, “The Belly Dance,” 131.

21 Najwa Adra, “Belly Dance,”, 36-37.

22 Ibid., 38.

23 Natalie Smolenski, “Modes of Self-Representation,” 57.

24 William C. Young, “Women’s Performance in Ritual Context: Weddings Among the Rashayda of Sudan,” in Images of Enchantment: Visual and Performing Arts of the Middle East, ed. Sherifa Zuhur (Cairo: American University in Cairo Press, 1998), 37.

25 Smolenski, “Modes of Self-Representation,” 57.

26 Young, “Women’s Performance,” 37.

27 Smolenski, “Modes of Self-Representation,” 55.

28 Adra, “Belly Dance: An Urban Folk Genre,” 36.

29 Van Nieuwkerk, ‘A Trade Like Any Other’, 121.

30 Ibid.

31 Ibid., 128.

32 Ibid., 129.

33 Shay, “The Male Dancer in the Middle East,” 63.

34 Smolenski, “Modes of Self-Representation,” 58.

35 Na’ima Akef and Fifi Abdo in particular are known for portraying this quintessentially Egyptian character.

36 Karin Van Nieuwkerk, “Changing Images and Shifting Identities: Female Performers in Egypt,” in Images of Enchantment: Visual and Performing Arts of the Middle East, ed. Sherifa Zuhur (Cairo: American University in Cairo Press, 1998), 31.

37 Smolenski, “Modes of Self-Representation,” 63-4.

38 Ibid., 64.

39 Van Nieuwkerk, “Changing Images,” in Images of Enchantment, 33.

40 Of course, we must also remember that Islam is not monolithic, nor does it have a hierarchy of religious leadership, such as Catholicism, to guide the ‘umma.

41 Adra, “Belly Dance,” 37.

42 Ibid., 38.

43 Anthony Shay, “Dance and Jurisprudence in the Islamic Middle East,” in Belly Dance: Orientalism, Transnationalism & Harem Fantasy, ed. Anthony Shay and Barbara Sellers-Young (Costa Mesa, California: 2005), 86.

44 Shay, “Dance and Jurisprudence,” 104.

45 Peter Schwartzstein, “The Dying Art of Belly Dancing in Conservative Egypt,” Vice, November 20, 2013, accessed December 30, 2013, http://www.vice.com/read/the-dying-art-of-belly-dancing-in-conservative-egypt.

46 Adra, “Belly Dance,” 38.