The term “Orientalism” holds within it a multitude of meanings from benign to controversial. Many scholars have dedicated insightful papers, essays, and books—and, indeed, entire careers—to the subject, and this chapter is only meant as an introduction to the concept as well as the issues surrounding its discourse. Anything more than a basic primer is beyond the scope of this study guide, and we encourage you to seek out the sources cited.

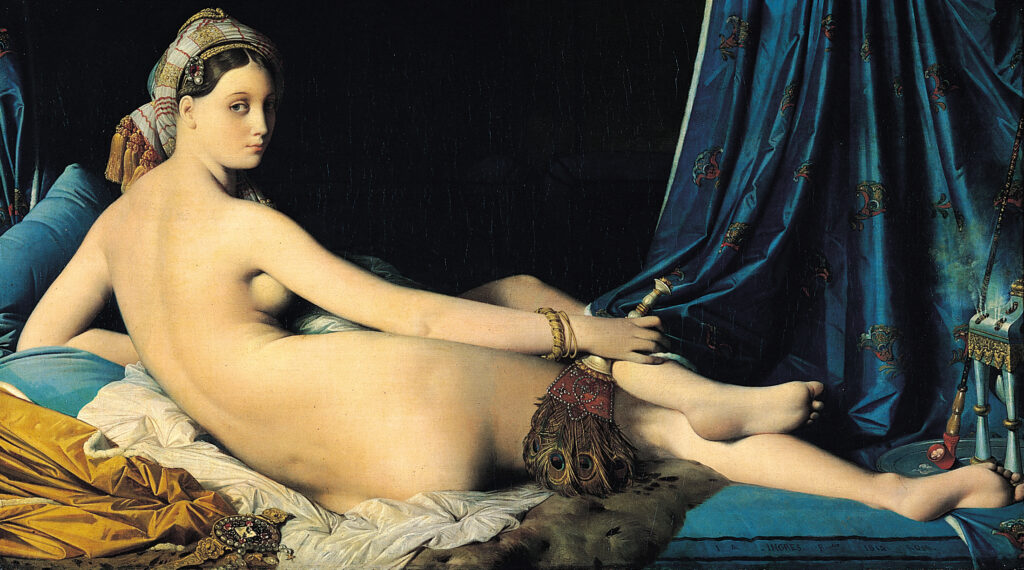

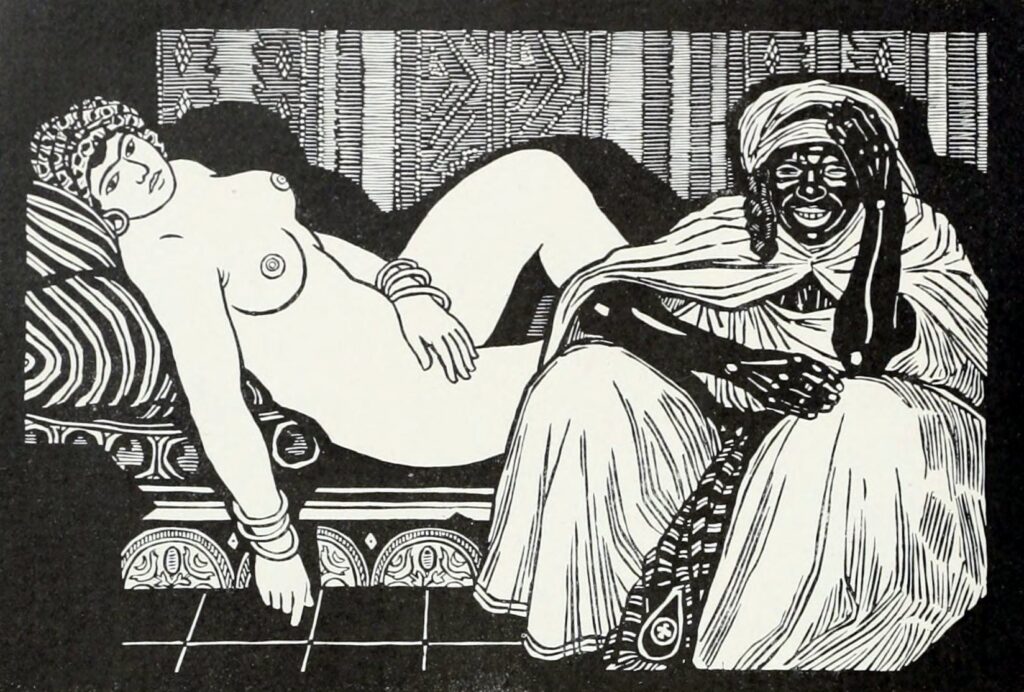

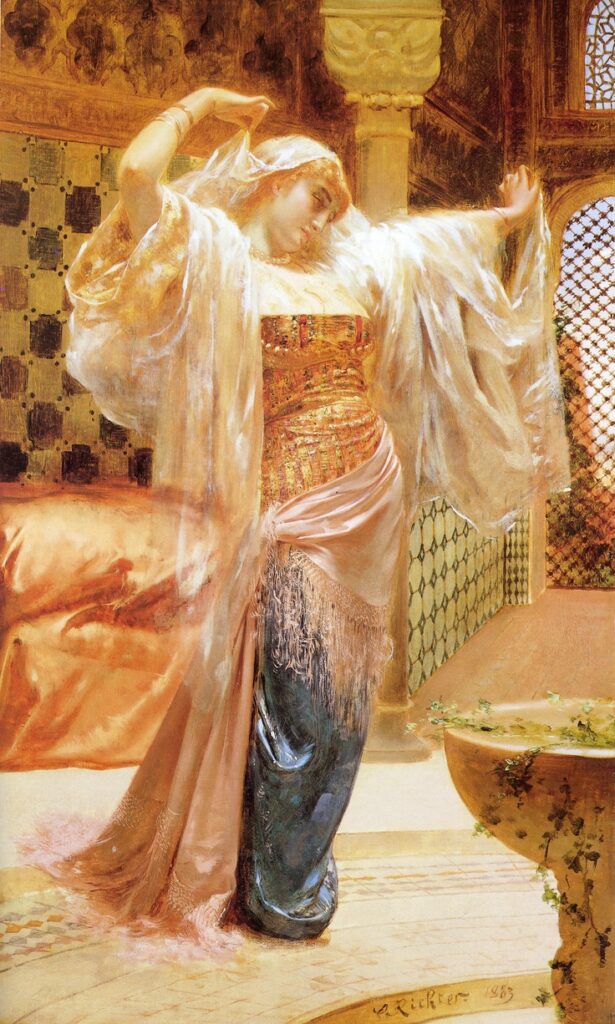

One very basic interpretation of the word “Orientalism” is that of the art movement by European, mostly French, painters of the late 19th century who specialized in “Oriental” (meaning, at the time, “Eastern:” mostly Ottoman, Middle Eastern, and North African) subjects. European men painted the majority of these works, and while some painted relatively accurate scenes of what they observed on their travels, with a dash of fantasy, but sometimes they painted what they imagined to be true—or what they wished to be true—such as scenes set in the interiors of harems and female bath houses, which were and are realms from which men are forbidden. These images greatly influenced how Europeans perceived the Middle East, regardless of their (in)accuracy.

A second meaning is used to describe the study of the Middle East and North Africa—the “Orient,” as opposed to the West, or “Occident.” Recently, the term itself has not been used much in popular contexts in the United States; it has been relegated to the older generation of academic scholars who pioneered the field of Middle Eastern studies. However, in the United Kingdom and Europe, it is more common in academic contexts.

A third, and more current interpretation is how the late Edward Said (a Palestinian scholar raised and educated in the United States) used it in his seminal work Orientalism (1978). For Said, Orientalism is a social and political construct that has lead to the development and study of the concept as an academic discourse in the fields of literature, cultural critique, performance studies, film studies, art history, and many others. He described Orientalism as a “fundamentally […] political doctrine willed over the Orient because the Orient was weaker than the West, which elided the Orient’s difference with its weakness.” ¹ His argument is that by simplifying the Orient (for him, and for the purposes of this study guide, this means mostly the Arab world, but includes the former Ottoman Empire and North Africa), the imperialist western nations were able to exert political influence and label Arabs as “other,” uncivilized, and immoral. By doing so, as Anne Rasmussen notes, “Orientalism served as a rationale for British and French political and intellectual imperialism.” ² Said’s Orientalism, according to historian Adam J. Silverstein, chastised Western scholars of Islam and the Middle East for “creating a field of study that is condescending towards and critical of the Muslim societies that they study.”

Silverstein elegantly distills Said’s thesis into three main points: the first is that “Orientalism has tended to be ‘essentialist’, assuming as it does that […] Near Easterners […] have an essential, unchanging nature that can be identified, described, and controlled politically.” The second is that Orientalism as a doctrine of thought, “especially as practised by British and French scholars, has been politically motivated,” in that if these scholars could show that the “nature” of Arab or Muslim societies is “inferior to […] the West, then Western political domination of Arabs and Muslims can be justified.” The third and final point is that “that these flawed impressions about the inferior essence of ‘Orientals’, and the need to consider the East only as it relates to the West, have been enshrined in a self-perpetuating and flawed field of study.” ³

One identifying characteristic of Orientalism as discourse is the portrayal in visual arts, writing, and advertising of a timeless “Orient,” unchanging and eternal, a place on which Western scholars, artists, and writers have ascribed their own desires, fantasies, and fears. Said states, “The Orient was almost a European invention, and had been since antiquity a place of romance, exotic beings, haunting memories and landscapes, remarkable experiences.” ⁴ Indeed the very word “Orient” itself is not specific and can mean anywhere from North Africa to East Asia, a span of geography that contains a multitude of peoples, languages, ethnicities, political conflicts, and cultures. Anne Rasmussen says that the idea of the “Orient” was often more important to Europeans than the reality; their image was romantic and invented.⁵ Judy Mabro says that Europeans in the Middle East were “more interested in finding links with the past to demonstrate that Oriental society had not changed for thousands of years” ⁶ than they were in the realities of the region; in fact, many travelers and tourists were disappointed when they arrived in the Middle East when they found it was not the “Arabian Nights” fantasy they wanted to experience. Rebecca Stone notes that the the West has “long made the Middle East an accomplice to its dreams and fantasies,” ⁷ as seen in the many works by artists such as Eugène Delacroix, Jean Léon-Gérôme, and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, who painted harem beauties (pale-skinned, of course), dancers, and courtesans. In her examination of Western representations of Arab women, Amira Jarmakani says that the Middle East “appealed to Delacroix because he perceived it to be untouched by the continuously progressing blade of modernization.” ⁸

The barefoot dancers of the late 19th and early 20th century also romanticized the East, culminating in Ruth St. Denis’s “construction of a spiritually mysterious Orient as the source of her positive reception in elitist art and theatre circles.” ⁹ Rasmussen also says that the Orientalist framework evident in Middle Eastern nightclubs in the United States during the 1950s and 1960s “included a family of ideas and images which played upon tantalizing and fantastical accounts of the exotic, the sensual, and the mysterious aspects of this antiquated, faraway land.” ¹⁰

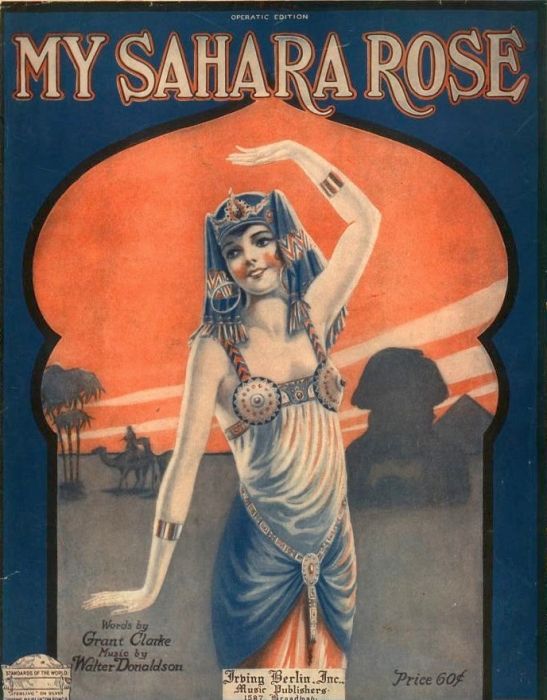

The “Orient” as a locus for fantasy, also becomes a homogenous land without ethnic or geographic distinction; in the mind of the Orientalist, East Asians, Arabs, South Asians, and North Africans all live in close proximity and share the same stereotyped characteristics. Many of the songs written to capitalize on Egyptomania conflate these “exotic” locales; the sheet music for the song “My Sahara Rose” shows a pyramid and sphinx on the cover, only for the lyrics to reminisce about being in “old Baghdad.” ¹¹ Many 20th century films dispose of real Middle Eastern locations at all; communications scholar Jack Shaheen compiled a list of made-up place names¹² for a “mythical, uniform ‘seen one, seen ‘em all’” setting that he calls “Arab-Land,” such as Abistan, Karamesh, and Bari-Bari.¹³ Hollywood Arabs are also subject to being reduced to being indistinguishable from each other, such as in the film Hostage (1986) where a US ambassador says, “I can’t tell one [Arab] from another. Wrapped in those bed sheets they all look the same to me.” ¹⁴

Many Westerners at the turn of the 20th century viewed the the cultures of the Middle East as technologically inferior, disorganized, untrustworthy, and incapable of self rule, an attitude traceable to colonial exploration and expansion beginning in the 16th century. Arguably, Europeans based this notion partially on political events in the Middle East at the time, as the Ottoman Empire gasped its last breaths and was known as the “Sick Old Man of Europe,” and the Ottoman vassal states and vilayat slipped away from direct rule from Istanbul. The idea also has roots in social Darwinism, which proposed that some races (i.e., white and European) were biologically superior to others (i.e., anyone not white and European),¹⁵ as seen in the organization of ethnic pavilions at the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893 with the “least civilized” (such as the Chinese Village and American Indians) being placed farthest from the fair’s entrance and the “most civilized” ¹⁶ (most European, such as the Irish Village) being placed closest. ¹⁷ Said also emphasizes that this idea of “Oriental backwardness, degeneracy, and inequality” can be found in many “scientific” treatises on race and ethnicity in the late nineteenth century. ¹⁸

Indeed, when we read the writings of pre-20th century European travelers in the Middle East, there are many examples of this attitude. We also see this sentiment in stereotypes about the Arab world in how male Arabs (and Muslims) are labeled either as violent terrorists and/or “backward” and technically-challenged religious extremists. In his comprehensive catalog on the (mis)representation of Arabs and Middle Eastern people in feature-length films, Jack Shaheen says that in innumerable films, Hollywood portrays Arabs as “brute murderers, sleazy rapists, religious fanatics, oil-rich dimwits, and abusers of women.”¹⁹

In addition to being a general realm of fantasy, the “Orient” has been portrayed as an inherently erotic place.²⁰ Female Arabs are depicted as passive slaves and harem girls who lounge around waiting to pleasure their sultan or as sultry femme fatales who use their exotic wiles to tempt unsuspecting Western men. Art historian Lynn Thornton tells us that in 18th-century England the word “Turkish” was “synonymous with naughtiness,” as evidenced in the “number of indiscreet encounters involving characters in Turkish dress at masquerades.” ²¹ In her essay about Ruth St. Denis’ Radha, Jane Desmond says “the East’s otherness offended European standards of sexual propriety, threatened domestic seemliness.” ²² In his examination of representations of the Middle East in Western music, Locke points out that “in most Orientalist songs the Middle East itself becomes eroticized, a realm in which issues of power and control can be, precisely, forgottenby the happily complicit listener.” ²³ In particular, the idea of the harem with its nubile bathing beauties contributed to this perception. In her essay on Orientalist films, Ella Shohat says “Western obsession with the harem […] authorized the proliferation of sexual images projected onto an otherized elsewhere,” ²⁴ such as in the 1943 film Coney Island, in which an American looking after a Turkish soldier’s harem sings, “wives for breakfast, wives for dinner, wives for supper time; I’ve got a thousand wives; And ev’ry one of them has got a perfect figure.” ²⁵

As an extension of being a land of sexual permissive locale, many examples of Orientalist literature, art, and film portray the the Middle East as fundamentally and archetypally female— weak, passive, languid, less intelligent, veiled and hidden, and mysterious. Indeed, in his essay “Orientalism Reconsidered,” Said wrote that Orientalism can be seen as “male gender dominance, or patriarchy, in metropolitan societies: the Orient was routinely described as feminine, its riches as fertile, its main symbols the sensual woman, the harem, and the despotic—but curiously attractive—ruler.” He adds that “Orientals, like Victorian housewives, were confined to silence,” such as in Gustav Flaubert’s autobiographical account of his night with the ghawazi courtesan Kutchek Hanem, in which, as Said says, “she never spoke of herself […] He spoke for and represented her.” ²⁶ Shohat points out that the idea of non-European lands as being “virgin” and passive dates back to the late Renaissance, as European nations began their exploration and colonization of the New World. ²⁷ Locke points out that in Western Orientalist music, “Arab hostesses, Sheherazade, and odalisques” show that in Western music the emphasis on a “mysterious female sensuality [is] the chief signifier of the imagined Middle East.” ²⁸ Many tobacco advertisements of the early 20th century, with their friendly sultans and languid harem beauties in two-piece belly dance costumes, reinforce, as Amira Jarmakani says, “the notion that the Orient is a feminized […] setting.” ²⁹ Shohat says that the propensity for portraying “non-Occidental” lands as feminine persisted in early film, such as D.W. Griffith’s epic Intolerance (1916)—with its sexual excess—and Cecil B. De Mille’s Cleopatra (1934)—in which the title role is not only sexually manipulative but is addressed as Egypt itself. ³⁰ By portraying the imagined Orient as female, many European men believed it their right and their duty to claim power over it, thus justifying colonialism and imperialism in the region.

However, as many scholars argue, the imagined feminine qualities of the Orient also pose a threat to Western, and by extension, male power. Alexandra Kolb says that “like femininity in patriarchal cultures, oriental culture in the West is seen as the exotic ‘other’ that threatens male dominance.” ³¹ By extension of the idea of the Orient as woman, the belly dancer, veiled woman, and the “harem girl” became not only images of what a Western man of priviledge could find (and exploit) in the Middle East, but symbols of the Middle East—and its perceived depravity, oppression, and indolence—itself. Kristin McGee notes, “one of the most enduring symbols of the West’s representation of the harem has remained the belly dancer.” ³² It was perhaps, as Rebecca Stone says, “women, especially women as dancers, that evoked the strongest image of exotic face of the ‘Orient’, her beauty and mystique to be slowly unconvered.” ³³

Recent scholarship on belly dance itself examines how Said’s definition of Orientalism reveals similar tensions in our own art form as women³⁴ seek out the “exotic Orient” as a vehicle for self-discovery, self-esteem, and individual empowerment. Donnalee Dox notes that Western belly dancers have used Orientalist imagery as a “celebration of alternatives to Western patriarchy [and] materialism,” transforming the harem, veil, and perceived secrecy of the Middle East into “the persistence of ancient wisdom in the modern world, and the uncontested value of open self-expression.” ³⁵ Feminist scholar Maira Sunaina argues that after September 11, 2001, the adoption of belly dance by white American women is a manifestation of a desire by these women to not only liberate themselves individually, but also of the perceived oppressed and veiled Arab/Muslim woman living in fundamentalist societies.³⁶

Many postmodern theorists have criticized belly dance in the West and its practitioners for perpetuating Orientalist tropes, colonialism, and gender essentialism. Indeed, well-established scholars Anthony Shay and Barbara Sellers-Young wrote in 2003, “belly dancing, as a mode of expression and style of performance, is an example of a genre of performance that is an extension of the process of Orientalism and a contemporary discourse on power.” ³⁷ They also say that Westerners have “relentlessly” romanticized Middle Eastern dance, especially what we call “cabaret” style, with “caliphs, sultans, sheikhs, slave girls, veils, harems filled with scantily clad beauties, caravans, and mosques and minarets” appearing as “familiar images in moving pictures, Broadway and Las Vegas performances, and the many publications for belly dance hobbyists and aficionados.” ³⁸ Donnalee Dox observes that many Western belly dance studios display reproductions of Orientalist paintings, where they “provide inspiration despite their European provenance and perspective.” ³⁹ Nader, a Palestinian-American, told Maira Sunaina that his mother “always objected to belly dancing as very ‘Orientalist.’” ⁴⁰

Many dancers, Shay and Sellers-Young point out, have used the idea of the Orient as an “empty location” for the “construction of new fantasy identities.” ⁴¹ In her work on the American fascination with Argentinian tango, Marta Savigliano says, “Exoticism is a way of establishing order in an unknown world through fantasy,” but it is the “seemingly harmless side of exploitation, cloaked as it is in playfulness.” ⁴² Shay and Sellers-Young also point out that the adaption of Middle Eastern-sounding stage names by American and European dancers is an extension of this phenomenon, and that words such as “allure” and “mystique” appear often in belly dance publications.⁴³ In her examination of the relationship between political tensions between the Middle East and the United States and the resurgence of interest in belly dance after September 11, 2001, Maira Sunaina observed that for many women, belly dance is “a way to conjure up a certain kind of ‘glamorous’ self or stardom.”⁴⁴ Sunaina even goes so far as to call this phenomenon of dress-up “Arab-Face:” a form of “racial masquerade” akin to the American minstrel shows of the 18th century.⁴⁵ Dox notes that many Western dancers in their quest for fantasy, “find themselves performing this cultural Other and playing into Western expectations of authentic belly dance,”⁴⁶ often ignoring the realities of the political, social, and cultural of the Middle East itself.

Said’s Orientalism as well as Orientalism as a theory and thought doctrine have not been without criticism. Silverstein outlines the flaws that critics of Orientalism have espoused since the book’s publication in 1979. One being that in the 19th century, at the height of European colonialism in the Middle East, most scholars were actually German, and not British or French. Another is that Said ignores many of the academic contributions that European scholars of the Middle East have made to the field of Islamic studies.⁴⁷ Other scholars have claimed that Said himself relies on essentialist tropes of “East” and “West” in order to support his thesis, and that Said neglects to speak to non-European imperial powers (such as Japan).

The content from this post is excerpted from The Salimpour School of Belly Dance Compendium. Volume 1: Beyond Jamila’s Articles. published by Suhaila International in 2015. This Compendium is an introduction to several topics raised in Jamila’s Article Book.

If you would like to make a citation for this article, we suggest the following format: Keyes, A. (2023). Orientalism: A Primer for Practitioners of Oriental Dance. Salimpour School. Retrieved insert retrieval date, from https://suhaila.com/orientalism-a-primer-for-practitioners-of-oriental-dance

1 Edward W. Said, Orientalism (New York: Vintage Books, 1978), 204.

2 Rasmussen, “‘An Evening in the Orient’,” 173.

3 Silverstein also points out that Said was not the first to identify this inclination; in the early 1940s, Sati al-Husri, a Syrian intellectual and leading proponent of Arab Nationalism, argued that “Western books on ‘Arab’ history are ‘biased […] tools of the imperialists who have always attempted by all means available to suppress or distort historical consciousness in order to perpetuate their rule.’” Silverstein, Islamic History, 80, 97-8.

4 Said, Orientalism, 1.

5 Stone, “Reverse Imagery,” 248.

6 Mabro, Veiled-Half Truths, 160.

7 Stone, “Reverse Imagery,” 248.

8 Amira Jarmakani, Imagining Arab Womanhood: The Cultural Mythology of Veils, Harems, and Belly Dancers in the US (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008), 40.

9 Kristin McGee, “Orientalism and Erotic Multiculturalism in Popular Culture,” Music, Sound, and the Moving Image 6:2 (2012): 211. For an in-depth critique of St. Denis’ Radha, see Desmond, “Dancing Out the Difference.”

10 Rasmussen, “‘An Evening in the Orient’,” 173.

11 Brier, Egyptomania, 160.

12 Many of the made-up names for Middle Eastern locales contain the suffix “-stan,” which is not Arabic or Turkish at all. It is, in fact, an Indo-Iranian word, and is common in Iran and Central Asia to mean “place” or “country,” as in Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Uzbekistan.

13 Jack Shaheen, Reel Bad Arabs: How Hollywood Vilifies a People (Northampton, Massachusetts: Interlink Publishing Group, 2001), 8, 554.

14 Shaheen, Reel Bad Arabs, 9.

15 The Arab- and Muslim-ruled world had also gradually lost political, philosophical, military, and scientific influence beginning in the late 15th century as Western Europe ushered in the periods of the Renaissance and later the Enlightenment. In the early 20th century, as the Ottoman Empire was increasingly unable to rule its vast territory, both Great Britain and France colonized the Middle East, taking control of North Africa, the Levant, and the Arabian Peninsula. They arbitrarily divided the land between them (and with Russia) under the Sykes-Picot Agreement, which lead to the current, and often problematic, borders and countries. For more on this topic, we recommend David Fromkin’s book A Peace to End All Peace for an accessible, yet in-depth, history of the creation of the modern Middle East.

16 Some ethnic exhibits, however, such as the Japanese Bazaar, were placed in accordance with how much money their managers had paid for their place on the Midway, with the ones who had given more generously nearer to the fair’s entrance.

17 Carlton, Looking for Little Egypt, 25.

18 Said, Orientalism, 206-7.

19 Shaheen, Reel Bad Arabs, 9. Shaheen labels each of the films profiled in his over 500-page book according to the stereotype presented, such as “Villains,” “Maidens,” “Sheikhs,” and the telling category “Palestinians.”

20 Arguably, this perception has changed in recent decades, beginning with the proliferation of Islamic terrorist attacks against European and US targets in the 1980s; the Orient as an imaginary land today is not so much perceived as an erotic place as it is a dangerous one.

21 Lynne Thornton, Women as Portrayed in Orientalist Painting (Paris: ACR Edition, 1985), 118.

22 Desmond, “Dancing Out the Difference,” 262.

23 Ralph P. Locke, “Cutthroats and Casbah Dancers, Muezzins and Timeless Sands: Musical Images of the Middle East,” 19th Century Music 22:1 (1988/1989): 36.

24 Ella Shohat, “Gender and Culture of Empire: Towards a Feminist Ethnography of the Cinema,” in Visions of the East: Orientalism in Film, ed. Matthew Bernstein and Gaylyn Studlar (New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1997), 47.

25 Shaheen, Reel Bad Arabs, 142.

26 Said, quoted in Kolb, “Mata Hari’s Dance,” 64; and Said, Orientalism, 6.

27 Shohat, “Gender and Culture,” 20.

28 Locke, “Musical Images,” 36.

29 Jarmakani, Imagining Arab Womanhood, 105.

30 Shohat, “Gender and Culture,” 23.

31 Kolb, “Mata Hari’s Dance,” 64.

32 McGee, “Orientalism and Erotic Multiculturalism,” 215.

33 Stone, “Reverse Imagery,” 249.

34 Most of the scholarship focuses on white, mostly middle-class, American women, although a few publications touch on Middle Eastern women seeking to connect with their own heritage, such as Lebanese-American author Anne Thomas Soffee who wrote a humorous biographical account of her venture into Oriental dance in central Virginia after a devastating break-up in Snake Hips: Belly Dancing and How I Found True Love (Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2002). The recently published Belly Dance Around the World: New Communities, Performance and Identity, ed. Caitlin E. McDonald and Barbara Sellers-Young, looks at belly dance communities in the England, New Zealand, and India; but English-language publications do not appear to have explored in-depth the adoption of the dance in Europe or East Asia (belly dance is extremely popular in Germany, Russia, China, and Japan).

35 Dox, “Dancing Around Orientalism,” 53.

36 See Sunaina Maira, “Belly Dancing: Arab-Face, Orientalist Feminism, and U.S. Empire,” American Quarterly, 6:2 (2008): 317-345, accessed January 5, 2014, http://wayneandwax.com/pdfs/maira-arabface.pdf.

37 Anthony Shay and Barbara Sellers-Young, “Belly Dance: Orientalism—Exoticism—Self-Exoticism,” in Dance Research Journal, 32.

38 Ibid., 27.

39 Dox, “Dancing Around Orientalism,” 58.

40 Maira, “Arab-Face,” 339.

41 Shay and Sellers-Young, introduction, 14.

42 Ibid., 31.

43 Ibid., 27.

44 Maira, “Arab-Face,” 318.

45 “Blackface” has its origins in the American minstrel shows of early- and mid-19th century. The minstrel shows originally involved white performers wearing dark makeup and performing as African Americans—who at the time were still slaves in the southern American states—and often faced great discrimination throughout the rest of the country. Later, some African Americans created their own minstrel troupes, sometimes wearing dark makeup to emphasize their skin color. These shows enjoyed great popularity until the late 1800s, when vaudeville became the common live entertainment of choice (although there are certainly crossover themes in both minstrel shows and vaudeville). Some scholars argue that minstrel shows provided a means of independence and liberation for the black performers who performed in them, while others maintain that the shows only perpetuated racism against and stereotypes (such as the “Dandy Negro” in top hat and tails or the “Happy-Go-Lucky Darky” who complies with his master’s wishes) of African Americans. Darkening the skin to portray “ethnic” characters was not uncommon at the turn of the century; Vadislav Nijinsky, in order to play the Golden Slave in the Ballets Russes’ Schehérézade, for example, painted his body brown to show the audience that his character was darker skinned. Later, in the popular film adaptation of the musical West Side Story (1961), actors portraying members of the Puerto Rican gang, the Sharks, also wore dark makeup to emphasize their “otherness” in contrast to the white gang, the Jets. For more on minstrel shows in the United States see Eric Lott, Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993), 3-31.

46 Dox, “Dancing Around Orientalism,” 58.

47 Silverstein, Islamic History, 98-99.