Jamila was very much against the Hollywood image of the belly dancer; she felt American films took the stereotype entirely too far so that dancers became shallow caricatures. She also found the choreographies performed by the actresses in these movies offensive, and having little-to-no relation to real Middle Eastern dance.

What America knew of Middle Eastern music and dance was through the distorted music productions of Hollywood. Yvonne De Carlo and Rita Hayworth were featured in several Biblical blockbusters, choreographed by Hollywood modern jazz dancers who interpreted Middle Eastern dance in jerky spasms, which were painful to watch. After seeing Rita Hayworth in Salome, I thought, “Was I the only one who knew of Egyptian films being shown monthly in Los Angeles? Or wasn’t anyone interested in authenticity?”

Later, in an interview with San Francisco’s PBS station, she said, “Most of the choreographers in Hollywood were modern dancers who interpreted the dance all wrong, like in Salome (1953) with Rita Hayworth. My god, that wasn’t Middle Eastern dance. That was an American version of Middle Eastern dance.”¹

Indeed, Hollywood’s Orient, as portrayed in films such as Kismet (1920), The Sheik (1921), and The Thief of Baghdad (1924), was greatly influenced by Russian ballets and costumes² as well as Western misconceptions about Arab women, clothing, and dance. Beginning with the invention of moving pictures themselves, Hollywood has been producing films with Orientalist themes, beginning with Intolerance in 1916. Production studios often referred to these films as “T and S” movies, meaning “tits and sand.” The Orient of Hollywood was, according to scholar Rebecca Stone, a “place of adventure, mysterious beauties, untold riches, and unbridled lust.”³ Films such as Cleopatra (1963), Baghdad (1949), Kismet (1955), and Sons of Sinbad (1955) often portrayed Eastern women as scantily-clad exotic dancers who performed in harems or at royal feasts for the pleasure of men. As Jamila herself said, the dances in these films rarely bear any resemblance to Middle Eastern or North African dances (unless they featured professional Oriental dancers), but instead are an amalgamation of Arab, Persian, Chinese, and/or Indian dances; American and European interpretations of Middle Eastern dance; American erotic dances; and Western dance forms such as ballet.

A popular character in these “T and S” films was the femme fatale: the exotic, mysterious Oriental woman, who is charming, seductive, and ultimately dangerous for the films’ often white, male hero. The archetype of the femme fatale has its modern origins in the late 19th century, in characters such as Oscar Wilde’s erotically-charged Salome, the real-life persona of Mata Hari, and the historic figure of Cleopatra VII. Many scholars of Orientalism claim that this image of the Oriental woman in popular culture has misogynist and racist implications against women, the people of the Middle East, and ultimately, against women of Middle Eastern origin.⁴ That said, it is impossible to deny the impact and influence these characters have had on not only the image of belly dance in popular media, but also on the dance’s practitioners.

Before the invention of the moving picture, the social climate was just right for a female character with sexual, social, and political power. In the late 19th and early 20th century, women wore corsets (arguably a physical representation of their social and psychic condition), were expected to marry, have children, and tend to their domestic duties. Some notable women actively worked for suffrage, independence, the right to divorce and own their own property, and even have control over their own sexuality. This movement, known as the first wave of feminism, caused upset in the Victorian social order, particularly traditional gender roles and expectations. Scholar Toni Bentley writes, “fears about the sexual woman were especially prevalent in both Europe and America during the late 1800s as a ‘medical’ preoccupation with the virus of female insatiability gathered momentum.” She also comments that the legalization of divorce in France, and the rise of industrialization, which both changed and challenged existing gender roles, caused a sense of insecurity among men at the time.

At this time, the femme fatale and shortly thereafter the vamp (short for “vampire”)—a seductive, sadistic, and independent woman whose sole mission was to destroy men—became part of the Western consciousness and entertainment mythology, with characters such as Cleopatra and Salome appearing in paintings, sculpture, dance, theater, and film.⁵ The new Hollywood vamp wore costumes influenced by Leon Bakst’s Orientalist designs for the Ballets Russes,⁶ emphasizing her exotic character and her otherness. Women were especially attracted to this new archetype, as they viewed her as liberated, powerful, and independent.⁷

In the next section we explore some of these historical, fictional, and mythological femme fatales, examining their stories and how they have been portrayed in popular arts, culture, and performance.

Cleopatra: The Last Pharaoh

Of the Hollywood femmes fatales, Cleopatra is one of the most famous. On screen, she used her sexuality to seduce Caesar and Marc Antony; however, the historical Cleopatra was likely more savvy than sensual. A shrewd politician, she ruled as the last pharaoh of ancient Egypt. Surrounded by popular myth and mystery, many dramatizations depict her as a beautiful and cunning temptress. Indeed, ancient sources, such as Plutarch’s Life of Antony, speak of her great beauty, but they also state that it was her intelligence that made her even more attractive. A member of the Ptolemaic Dynasty that ruled Egypt after Alexander the Great’s death, she was the only Ptolemaic leader to learn the Egyptian language. Her forerunners refused, preferring to only speak Greek. It is nearly impossible to discuss the famed queen Cleopatra VII Philopator (b. 69 BCE – d. 30 BCE) without discussing her political alliances and intrigues.

At age 14, she first ruled jointly with her father, Ptolemy XII Auletes, then when she was 18, with her brothers, the 10-year-old Ptolemy XIII—to whom she was married, according to tradition—and Ptolemy XIV. Political and economic troubles, famine, and deficient Nile floods complicated the first three years of their reign. Cleopatra, refusing to share power with her brother/husband, removed his name and face from official documents, such as coins, in 51 BCE. In 50 BCE, a bloody conflict with the Gabiani—Roman troops left in Egypt to protect Cleopatra’s father—forced Cleopatra to flee into exile with her only remaining sister, leaving her brother/husband to become the sole ruler of Egypt.

In 48 BCE, Egypt became involved in the conflict between Julius Caesar and the military leader Pompey. Pompey fled to Alexandria, the capital of Egypt, where Caesar ordered his murder. Caesar came to Egypt, where he defeated Ptolemy XIII’s army at the Battle of the Nile, restoring Cleopatra to the throne with her youngest brother as co-ruler. Ptolemy XIII drowned during the battle. Famously, when Caesar was in Egypt (48-47 BCE), he and Cleopatra became lovers; she was 21 and he was 52.⁸ Cleopatra gave birth to a son that she claimed was his, and whom she named Caesarion, although Caesar refused to name him as heir, naming his grandnephew Octavian instead.

Cleopatra, her brother, and her son visited Rome in the summer of 46 BCE. The Roman people found the relationship between Cleopatra and Caesar scandalous, as Caesar was already married. After Caesar’s assassination in 44 BCE, she returned to Egypt. Her brother died mysteriously at this time; some believe that Cleopatra poisoned him. She then made Caesarion her co-regent and successor.

In an effort to consolidate her dynasty’s claim to the throne, she aligned with Mark Antony in opposition to Octavian. Anthony came to Egypt and was so captivated by the queen, that he stayed in Alexandria with her. They married according to Egyptian traditions, although he, like Caesar, was already married. With Antony, she bore fraternal twins and a son. In 33 BCE, relations between Mark Antony and Octavian broke down, and in 31 BCE Octavian convinced the Roman Senate to levy war against Egypt, leading to what is now known as the Battle of Actium. Cleopatra and Antony fled with their ships, and Octavian invaded Egypt. In 30 BCE, Antony’s armies defected, and Antony committed suicide. Cleopatra famously did the same; the popular belief is that she did so by letting a venomous cobra bite her. Ancient Roman sources generally agree with this idea; however, German scholar Christoph Schaefer claims that she poisoned herself with a combination of hemlock, wolfsbane, and opium.⁹ Egypt then fell to the Roman Empire, never to be an independent state again until after World War I.

In modern productions, the story of Cleopatra became one of decadence and sexuality. Davinia Caddy notes that the Ballets Russes production of Cléopâtre provided a typical Orientalist narrative: “the protagonist, scenery and costumes substituted the archetypal, placid world of nineteenth-century Romantic ballet with the colors, opulence, and appetite of an imagined East.”¹⁰

Salome and “Salomania”

The Victorian era transformed the unnamed New Testament character of Salome into the quintessential dancing seductress of the age. The character of Salome crossed class and theatrical lines, appearing on tawdry vaudeville stages to some of the most respected theater stages in Europe. Caddy says that through the works of artists from painter Gustave Moreau to writer Oscar Wilde to composer Richard Strauss, “Salome’s vampish attire and dangerous sexuality formed a contemporary fetish.”¹¹ By changing her story from one of little fanfare and gravity to that of the quintessential Oriental seductress, Salome became one of the hottest performance trends in the late 19th and early 20th century.

The historical Salome, if she had been a real figure, is believed to been born in 19 CE.¹² Mentioned in both the Gospels of Mark and Matthew, she is known only as the daughter of Herodias and stepdaughter of King Herod Antipas. She is, however, named in Flavius Josephus’ Jewish Antiquities, along with more detail on her family. None of the period sources reveal her age; some claim she was only a little girl at the time of the famous story, while others believe she had already reached puberty. The original story is this: King Herod requested that the daughter of Herodias dance before him and his court at a great gathering held on his birthday. The Gospel of Mark mentions nothing about her dance being seductive or sexual; it only says that her dancing pleased him, so much that he said she could ask for whatever she wanted in return for the performance. She consulted her mother, not knowing for what to ask; Herodias then asked for the head of John the Baptist, a prisoner of the king. Keeping to his oath, the king complied, and beheaded John, famously bringing his head into the gathering on a large tray. Josephus, however, makes no connection between Salome and the famous beheading; neither account makes any mention of how she danced, let alone whether or not she used veils.

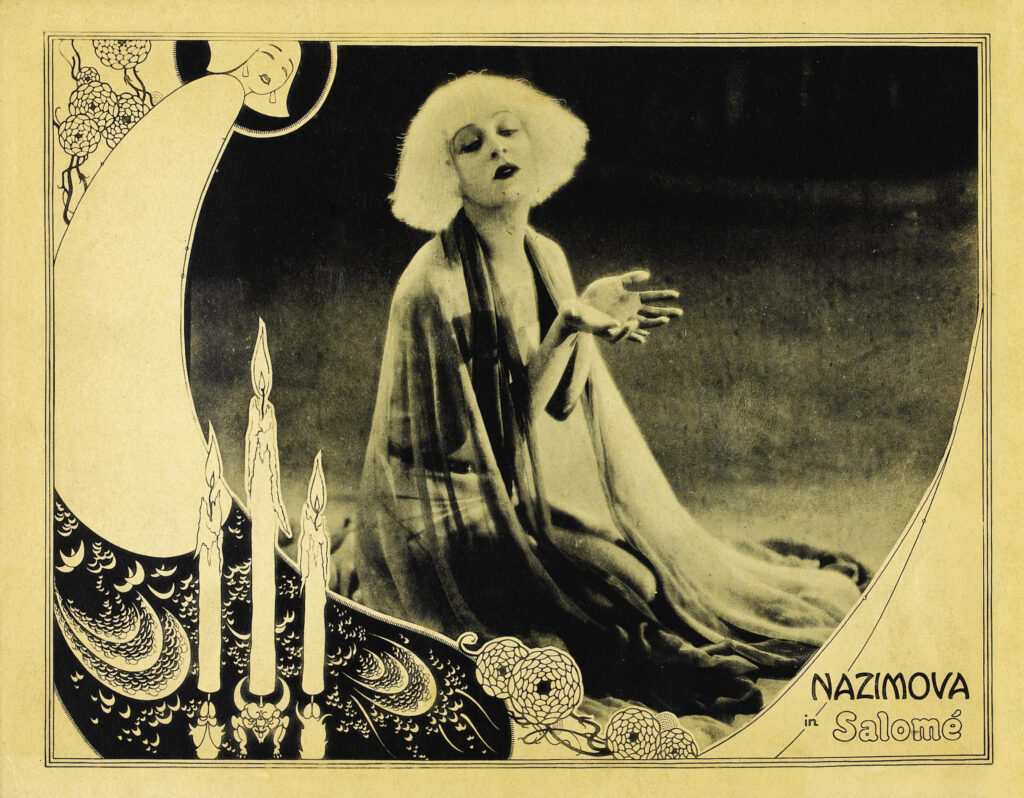

Nearly every age of European art has interpreted her story, although not nearly to the same degree of scandal and fame as during the Victorian age. During the Middle Ages, she was often shown as an acrobat, and during the Renaissance, a virgin beauty. The famed “Dance of the Seven Veils,” although arguably based in the ancient Mesopotamian myth of Inanna/Ishtar at the Seven Gates,¹³ was invented by Oscar Wilde for his play, Salome, in 1894, in an effort to scandalize his prudish Victorian audiences. In fact, at the time, British law prohibited the depiction of Biblical characters on stage; Wilde first wrote the play in French, then wrote an English translation. In Wilde’s play, Salome takes a perverse interest in John the Baptist who rejects her advances. In revenge, she, not her mother, asks for his head after her performance and kisses the severed head during the finale. The notoriety of Wilde’s Salome grew enormously after performances of Richard Strauss’ 1905 opera of the same name, which used Wilde’s play as its libretto¹⁴ and featured a “dance of the seven veils.” Wilde himself left little instruction for the dance itself other than a single stage direction: “Salome dances the dance of the seven veils.” Even so, Salome’s dance changed from the gymnastic and innocent dances of earlier times to what was basically one of the first “striptease” shows in modernity.¹⁵

The idea of Salome the temptress spread to the Ballets Russes, whose dancers used veils in some of their choreographies depicting Salome and Cleopatra. Between 1905 and 1918, performances of various interpretations of the “Dance of the Seven Veils” (now as a proper name; Wilde’s play used lower-case letters) had proliferated in both high art and vaudeville stages, in what is now known as Salomania. Impresario Florenz Ziegfeld included the character of Salome in his Ziegfeld Follies in 1907; the “Salome” feature was the show’s most successful act.¹⁶ The performance was so successful that the dancer who portrayed Salome opened a “school for Salomes” on the roof of the New York Theater, training dancers for the vaudeville circuit—“complete with a jeweled breastplate and papier-mâché heads,” according to Caddy—which produced one hundred and fifty Salomes per month.¹⁷ Salomania became so pervasive at the turn of the 20th century that wealthy women dressed as Salome and held Salome-themed parties.¹⁸ In 1908, Salomania had “broken out in full force.” In August of that year, there were four Salomes performing in New York, and by October there were twenty-four.¹⁹ By 1909, nearly every vaudeville and variety show in the United States had its own Salome,²⁰ performing in a “vaguely Eastern outfit” some variation on the dance of the seven veils.²¹ Music scholar Davinia Caddy notes that in addition to being a “vehicle for appropriation by […] feminism,” Salome also “emerged as a leading Orientalist figure” who was also a “bodily and sexual” self-indulgent archetype. Salome had become, Caddy tells us, “an Eastern vamp whose sexuality lures men into unthinkable schemes;” she was a powerful symbol of the liberated, bourgeois woman who wanted to be free of domestic roles and “assume a male prerogative.”²²

Even though Salomania as a social fad lasted for little more than two years,²³ these performances solidified the portrayal of Salome as the quintessential femme fatale in the late 19th and early 20th century. She left an indelible impression on the Western consciousness, shaping views of liberated women as dangerous and “Oriental” women as uncontrollable sexual “vampires” seeking to destroy men. Wearing neither shoes nor a corset, “Salome was a prime vehicle for self-expression, associated with just the sensual movement and ambiguous, transformative power the dancers sought,” says Caddy. In addition, Salome’s “Judean identity encouraged the connection between Orientalism and modern dance that would later influence not only the development of the style but also fan-magazine and Hollywood iconography.”²⁴ Indeed, American silent screen stars such as Theda Bara continued to capitalize and perpetuate this interpretation,²⁵ and the femme fatale in its various forms survives even today in films such as Chaterine Trammell as played by Sharon Stone in Basic Instinct (1992) and Irene Adler in BBC’s television series Sherlock as portrayed in “A Scandal in Belgravia” (2012).

Theda Bara (1885 – 1955)

Known for being the quintessential silent screen vamp, Theda Bara was born Theodosia Burr Goodman in Cincinnati, her father a Jewish tailor from Poland, her mother a Swiss French wigmaker.²⁶ Biographers say she had a relatively normal childhood, and when she was young, she already interested in acting; she was a member of her high school’s Dramatic Club, and for two years studied theater at the University of Cincinnati. She left her studies to move to New York City—a move reluctantly funded by her father—to pursue a career on the stage, and by 1910, she had roles in second parts at the Yiddish theater on the Lower East Side, but she had failed to land a role on Broadway.²⁷ She followed the prospect of performing in a Greek drama in Europe, but the project folded, and she returned to New York City.²⁸ At age 25, she was struggling financially when Fox Pictures director Frank Powell offered her the female lead in A Fool There Was (1915). Reluctant to involve herself in moving pictures—she fancied herself a stage actress only—she took the job.

William Fox, owner of the Fox studios, realized that such a character could not be played by a woman named Theodosia Goodman, or even Theodosia deCoppet, as was her stage name when she transitioned from stage to screen. The publicity department asked her to review her childhood nicknames—Teddy, Theo, and Theda—as well as familial surnames—Goodman, DeCoppet, Baranger—and created Theda Bara, with Bara being short for Baranger.²⁹

A Fool There Was, the story of a married diplomat who falls under the spell of a predatory woman, launched Bara into stardom. The press lauded Bara for her performance; the San Francisco Call & Post said, “Theda Bara was an instant triumph in the role of the vampire woman.” Her performance was so powerful that the dictionary added a new definition for, “Vampire: a woman who preys upon men. To vamp: to prey upon men, entice, inveigle, captivate.” ³⁰ With her dark hair and smoky kohl-rimmed eyes, Bara looked the part of the dangerous “Oriental” woman, an archetype that had already gripped the United States and Europe through numerous interpretations of the story of Salome. Indeed, an unknown person discovered, famously, that Bara is an anagram for “Arab,” giving credence to Bara’s Oriental origins.³¹ When Bara was filming Carmen in 1915, publicists at Fox realized that one could respell Theda as “Death:” the idea that Bara’s stage name could read “Arab Death” has only furthered the actress’ notoriety.³²

The Fox studios were unprepared for her popularity, and after billing her along side much-admired dramatic actress Nance O’Neil in a film based on Tolstoy’s The Kreutzer Sonata, but after that, she would never appear on screen with another woman.³³ She found herself typecast in a variety of films portraying dangerous women, in such films as The Devil’s Daughter (1915), Sin (1915), The Serpent (1916), The Vixen (1916), Cleopatra (1917), The Tiger Woman (1917), and Salome (1918). Bara eventually made forty-two movies, with forty of them between 1914-1919, and eleven in 1915 alone. She asked for roles other than the vamp, and did play them occasionally—such as in Camille (1917) and Romeo and Juliet (1916)—but her audiences wanted only to see her as the femme fatale.³⁴ Within a year, she had shot from unknown to superstar, receiving over 200 fan letters a day; 1,329 contained offers of marriage, and by the end of the year, 162 babies had been named “Theda.” ³⁵ At the height of her fame, Bara earned $4,000 per week.

Arguably, Bara was the first manufactured media star. In an effort to conceal her Middle-America roots, the publicity offices of Fox studios fed the newspapers carefully-constructed lies about her exotic origins. Norman Zierold notes that at the time, the public could hardly accept that someone who portrayed women as “so calculatingly seductive, so alluringly cruel, so wonderfully wicked could possibly be of American origin.” ³⁶ The Fox studios created countless fictions about her childhood and ancestry: that she was “born in the shadow of the Sphinx” in Egypt, raised on serpent’s blood, or even “unspeakably evil.” ³⁷ They lied about her parentage, saying she was the only child of French actress Theda de Lyse and Italian sculptor Giuseppe Bara,³⁸ as being the daughter of European artists was considered at the time quite avant garde. It appears that the public could not (or maybe would not) separate the woman from the characters she played or the media hype surrounding her dubious background, unaware that the film studio had constructed Bara’s alluring and mysterious public persona. Even today, the mention of Theda Bara evokes an image of a dangerously charming woman,³⁹ and Bara’s biographers find it difficult to separate the lies from the reality of her life.

In her early days of fame, Theda played along with the hype, speaking in heavy foreign accents during press conferences. She declared that she had been reincarnated four times, and in one of her lives she had lived in ancient Egypt,⁴⁰ herself the reincarnation of a daughter of Seti, a high priest of the Pharaohs.⁴¹ She also wore “many odd ornaments,” including an emerald ring given to her by a blind sheik in whose family it had been passed on for “more than 2,000 years.” ⁴² She even played up the vampire angle, saying, “The vampire that I play is the vengeance of my sex upon its exploiters. You see, I have the face of a vampire, perhaps, but the heart of a feministe [sic].” ⁴³

Bara felt the pressure of being labeled and typecast as a villainess, not only on the screen, but in real life, and told Fox studios that she wanted to “play a kind-hearted, lovable, human woman.” ⁴⁴ She was able to play more vulnerable characters, such as Juliet in Romeo and Juliet, but the viewing public was not interested in seeing her playing anything other than the vamp.

Amidst all the media hype, however, Bara ultimately bore the brunt of criticism and accusations of immorality. After her portrayal of Cleopatra, in the film of the same name (1917), many members of the public objected the to the film, speaking of its “wicked, suggestive” nature. One man at a meeting of the Women’s Club of Omaha specifically held to decry the film says “I must confess to being shocked at the movements of the actress,” while Mrs. C. W. Hayes, who presided over the meeting said that Cleopatra was “not fit for children to see.” ⁴⁵ In another incident, a woman in New York kicked a hole through the visage of Bara on a lobby poster, then wrote to the star to tell her it was worth the $10 to have the satisfaction of doing so; the woman closed her letter with, “Oh, how I hate you.” ⁴⁶ Her film Rose of Blood also faced scrutiny, when Chicago’s film censor requested that the United States Department of Justice prevent the film from being shown, but was denied as the United States Government decided it was neither a threat to morality nor the growing concerns related to World War I. ⁴⁷ The Fox studios played on the hype, billing Bara as the “Wickedest Woman in the World.” ⁴⁸ Unfortunately, a fire at a Fox storage facility in 1937 destroyed nearly all of Bara’s films, so we are unable to judge the film’s supposed depravity for ourselves.

Bara reluctantly played her last film vamp in Lure of Ambition (1919) to fulfill her contract with Fox. She then decided to return to the theater stage in New York, in The Blue Flame, where she played another variation of an immoral woman. Even though audiences flocked to see the performance, reviewers suggested that she should have remained a silent film actress, with the New York World saying that her lines had a “schoolgirl’s recitative [sic]” and “a western monotony.” ⁴⁹ No longer obligated to appear in any more films for Fox, Bara married Charles Brabin, an Englishman who had directed her last two pictures, 1921. ⁵⁰ She appeared in several more films, often playing the vamp, but made her last in 1925. The emergence of the Jazz Age and flappers—the new femme fatales who smoked, danced, drank, and wore short dresses—began to make the dangerous Oriental woman seem dated and passé. She retreated from the spotlight and into Beverly Hills society life, attending committee meetings of several charitable organizations. ⁵¹ In 1965, she died after a year-long battle with stomach cancer. For her contributions to the film industry, Theda Bara has been honored with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

The content from this post is excerpted from The Salimpour School of Belly Dance Compendium. Volume 1: Beyond Jamila’s Articles. published by Suhaila International in 2015. This Compendium is an introduction to several topics raised in Jamila’s Article Book.

If you would like to make a citation for this article, we suggest the following format: Keyes, A. (2023). Oriental Images in Hollywood. Salimpour School. Retrieved insert retrieval date, from https://suhaila.com/oriental-images-in-hollywood

1 “Salimpour, Syjuco, and Yi,” Spark, KQED Public Media for Northern California, San Francisco, California: KQED, May 7, 2008, accessed December 15, 2014. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9cIQytsr-rY.

2 Mernissi, Scheherezade Goes West, 71.

3 Stone, “Reverse Imagery,” 250. The image of the Arab has changed since the 1970s with the globalization of Islamic terrorism. Since then, Arabs have been increasingly portrayed as villains, such as suicide bombers, terrorists, and mujahidīn. See Jack Shaheen’s Reel Bad Arabs for an insightful analysis of the evolution of Hollywood’s image of Arabs in film.

4 Kolb, “Mata Hari’s Dance,” 64.

5 The idea of “woman as vampire” can be traced to a late 19th-century painting by Sir Edward Burne-Jones, which depicts a woman crouching over an unconscious man, aptly titled “Le Vampire.”

6 Gaylyn Studlar, “Out Salome-ing Salome: Dance, The New Woman, and Fan Magazine Orientalism,” in Visions of the East: Orientalism in Film, ed. Matthew Bernstein and Gaylyn Studlar (New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1997), 116.

7 Bentley, Sisters of Salome, 34.

8 “History: Cleopatra (c.69 BC – 30 BC),” BBC, accessed November 29, 2013, http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/cleopatra.shtml.

9 Melissa Gray, “Poison, not snake, killed Cleopatra,” CNN, June 30, 2010, accessed November 26, 2013, http://www.cnn.com/2010/WORLD/europe/06/30/cleopatra.suicide/index.html?_s=PM:WORLD.

10 Caddy, “Variations,” 47.

11 Ibid., 37.

12 Kultermann, “The ‘Dance of the Seven Veils’,” 188.

13 According to a popular version of this myth, Inanna—Mesopotamian goddess of love, war, fertility, and lust—descends into the Underworld through seven gates. At each gate she discards articles of clothing and jewelry, so that when she arrives in the Underworld, she is completely naked.

14 Deagon, “The Dance of the Seven Veils,” 243.

15 Bentley, Sisters of Salome, 30.

16 Ibid., 39.

17 Kultermann, “The ‘Dance of the Seven Veils’,” 205. Caddy, “Variations,” 37.

18 Shay, Dancing Across Borders, 9.

19 Bentley, Sisters of Salome, 39.

20 Ibid., 40.

21 Caddy, “Variations,” 37.

22 Ibid., 38.

23 Kendall, Where She Danced, 77.

24 Caddy, “Variations on the Dance of the Seven Veils,” 39.

25 Deagon, “The Dance of the Seven Veils,” 243-275.

26 For a comprehensive biography on Bara, see Eve Golden, Vamp: The Rise and Fall of Theda Bara (Vestal, New York: Emprise Publishers, 1996).

27 Pam Keesey, Vamps: An Illustrated History of the Femme Fatale, (San Francisco: Cleis Press, 1997), 73; and Norman Zierold, Sex Goddesses of the Silent Screen (Chicago: H. Regnery Co., 1973), 11.

28 Zierold, Sex Goddesses, 12.

29 Keesey, Vamps, 74.

30 Zierold, Sex Goddesses, 6.

31 Ibid., 12.

32 Ibid., 21.

33 Ibid., 8.

34 Keesey, Vamps, 76.

35 Zierold, Sex Goddesses, 25.

36 Ibid., 10.

37 Stone, “Reverse Imagery,” 255.

38 Pam Keesey, Vamps, 75.

39 Zierold, Sex Goddesses, 5.

40 Ibid., 28-29.

41 Eve Golden in Pam Keesey, Vamps, 75.

42 Antonia Lant, “The Curse of the Pharaoh, or How Cinema Contracted Egyptomania,” in Visions of the East: Orientalism in Film, ed. Matthew Bernstein and Gaylyn Studlar (New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1997), 91.

43 Zierold, Sex Goddesses, 15.

44 Ibid., 18.

45 Ibid., 4.

46 Ibid., 17.

47 Ibid., 39.

48 Ibid., 5.

49 Ibid., 46.

50 Ibid., 48.

51 Ibid., 55.