In addition to the hugely influential Ballets Russes, individual early modern dancers between 1890 and 1920 interpreted the Middle East and the amorphous Orient for new and excited audiences. These dancers were groundbreaking in their scope, not only for the world of modern dance that they helped to create, but also for Westerners interested in learning “Eastern” dances. Some of these modern dancers hardly studied the dances of the Middle East or South Asia, while others traveled there to learn the dance as it was performed “over there.” Such early twentieth century dancers and performers as Mata Hari, Ruth St. Denis, Maud Allan, Loïe Fuller, Isadora Duncan, and La Meri experimented with Eastern themes and imagery,¹ costuming, and choreographies with varying degrees of authenticity. Many of these new “barefoot dancers”, as they are often called, shed their corsets and drew heavily from and capitalized on the fashion of Orientalism and the fascination with the “exotic other. ²

Scholar Rebecca Stone reminds us that it is important to remember that when Oriental dance was staged, either in theaters or on film, it was almost always modified to suit Western aesthetics and sensibilities, as most Westerners preferred the Orientalist vision to the authentic dance forms.³ Shay, too, says that Western European and American audiences wanted their Orient—a homogenous region with little ethnic, linguistic, cultural, or political distinctions—to be filtered through white, most often American, bodies.⁴ That said, these pioneers of modern dance have left an undeniable impact on the development of dance, even in the recent stylizations of belly dance, with its inclusion of Middle Eastern and Indian goddess imagery and mythologies.⁵

Most of these early modern dancers, known as barefoot or “aesthetic” dancers, shared several characteristics: they mostly danced solo (sometimes framed by dancers or musicians in the background), performed barefoot, used actual natural settings by dancing outdoors or sets made to look that way, integrated clothing and props such as veils that enabled a wide range of movement. These women also represented a new interest in physical health, artistic reform, and activity in the open air, including dancing, opening doors to new forms of creative expression previously unavailable to Western women.⁶ Music scholar Davinia Caddy notes that these dancers fused ideas of “middle-class female gentility” while simultaneously encouraged freedom from late 18th-century gender roles and domestic expectations.⁷

Like in the Middle East, Shay tells us that for a woman to dance in public at this time was linked to prostitution, and the “worst fate imaginable for the middle and upper classes was the possibility that a son might marry an opera dancer, or worse, that a daughter might ‘trod the wicked boards.’” He also notes that for a woman to expose her bare foot was also considered indecent.⁸ These new barefoot dancers transgressed social expectations, breaking new ground for future dancers and performers around the world.

However, by differentiating themselves from being “sexualized dancing bodies” the female modern dancers of the late 19th and early 20th century enabled themselves to “gain legitimacy for themselves as artists (not objects) on the theatrical stage.”⁹ Dance scholar Anthony Shay says that the “search for spiritual meaning” was incredibly important for dancers like Ruth St. Denis and Isadora Duncan, which helped them distinguish themselves from being regarded as “tawdry” or even as prostitutes.¹⁰

Margaretha Geertruida “M’greet” Zelle MacLeod was born to a well-to-do family in the Netherlands, and was eldest of four children. After her father went bankrupt in 1889, she traveled to the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia) to answer a personal ad for marriage to a Dutch Colonial Army Captain, Rudolph Macleod. The marriage disintegrated in part to her husband’s alcoholism, outbursts of rage, and eventually abuse of Margaretha. In 1899, their two children became unexpectedly ill—the son, Norman John, died, but their daughter, Jeanne Louise, survived—likely poisoned by their nurse in revenge for Macleod’s outbursts.¹¹ Margaretha then turned to studying Indonesian traditions, joining a local dance company. In a letter to her relatives in Holland in 1897, she revealed her artistic name: Mata Hari, Indonesian for “sun” (literally, “eye of the day”). She would not use her stage name until much later.

She and her husband returned to Amsterdam in 1901 after Maclod resigned from the Army. She filed for a legal separation, and her husband gained custody of their daughter. Left with near nothing, she had an opportunity to reinvent herself and her life.¹² She moved to Paris in 1903, where she performed as a circus horse rider, posed as an artist’s model, and made her debut at the Museé Guimet in 1905 as a dancer. At first performing as “Lady Macleod,” a wealthy industrialist, Emile Guimet, suggested she choose something more Eastern, and she was then known as Mata Hari.¹³ She made her debut at Guimet’s museum for an audience of three hundred men and women. She portrayed herself as a Javanese princess, pretending to have been trained in the art of sacred Indian dance since childhood, complete with a statue of Shiva behind her and sandalwood incense filling the salon.¹⁴ Dance scholar Alexandra Kolb says that Mata Hari declared her ethnically stylized choreographies to be authentic Asian dances, though she possessed only a limited knowledge of Javanese and Sumatran dances.¹⁵

She was an overnight success, and dance scholar Jodi Bentley says that her admirers saw in her the “personification of a femme fatale,” as she had “captured the imaginations of the willing Parisians in their restless search for erotic entertainment.” ¹⁶ Her most famous act was her progressive removal of clothing until she wore only her bra and headdress; she did, however, sometimes wear a flesh-colored bodystocking. Alexandra Kolb notes that Mata Hari’s nudity was “extremely risqué,” but because it was couched in the context of being “spiritual” and “embedd[ed] into a religious Indian context,” her audiences perceived her performances as not so much lewd as they were enlightened, as they blended “sensual and spiritual elements.” ¹⁷ Considering that Mata Hari had very little formal dance training, she enjoyed a successful career in venues ranging from private salons to opera houses.¹⁸ Artist Erté, who created his first theatrical costume for Mata Hari in 1913, commented that she did not have much talent, but had fabricated such a story around herself to conceal any lack of it.¹⁹

Although reviews of her dances clearly describe her dances as being made of curvy, non-linear movements (as opposed to the geometrical patterns of ballet at the time), Mata Hari’s dancing did not appear to use hip isolations or emphasize the use of the abdominal muscles, as is characteristic of belly dance.²⁰ Even though she had likely studied Indonesian dance, at least at a beginning level, she probably did not have any first-hand knowledge of Indian or Middle Eastern dance, not that most critics or audience members seemed to notice or care.²¹ Kolb also claims that Mata Hari’s dancing was likely similar to that of American dance artist Ruth St. Denis, who began performing in Europe in 1906, a year after Mata Hari made her debut.²²

Like many of her contemporaries, her success spurred her to tour, starting in Madrid in 1906.²³ Her performances competed against other barefoot and Salome dancers, such as Maud Allan and Isadora Duncan.²⁴ After successful runs in Monte Carlo, Vienna, and Rome, her pride won the best of her when she attempted to join the Ballets Russes. After stripping completely nude in front of costume and set designer Leon Bakst and being rejected, she returned to Paris.²⁵

By 1910, she had influenced many imitators who saturated the burgeoning market for Oriental-style solo performances, causing a slump in Mata Hari’s performing career. However, by 1912, she had also become a high-class courtesan. After gaining weight and building a successful career servicing high-ranking military officers, politicians, and other influential international leaders, she gave her last public performance in 1915.

During World War I, she took advantage of her Dutch citizenship (the Netherlands remained neutral) and traveled between France and the Netherlands through Spain and Great Britain, seeking performance opportunities and clients. Toni Bentley notes that despite popular belief, the Germans did not ask Mata Hari to seduce the enemies; they did, however, as they did many civilians during the war, ask her to be a low-level informer.²⁶ The French and British thought her travels suspect, and she was arrested in 1916 on suspicion of espionage and brought to London where she was interrogated at Scotland Yard. She admitted to working for French intelligence; however, it is not clear if she lied to make herself seem more intriguing. In 1917, French intelligence agents intercepted a message from the German military attaché in Madrid, describing the activities of German spy “H-21,” whom they identified as Mata Hari herself. She was arrested that year in Paris and put on trial as a German spy, although neither the French nor British intelligence services could produce concrete evidence against her at the time. Documents declassified in the 1970s suggest that she had indeed spied for the Germans under the codename H-21; however, declassified documents from the French Ministry of Defense suggest otherwise.²⁷ She was executed by firing squad in October of 1917 at the age of 41. Dance scholar Alexandra Kolb notes that Mata Hari’s image as a femme fatale “indeed found its ultimate expression in her execution, which was seen by some as fair punishment for a sordid lifestyle.”²⁸

Loïe Fuller (1863 – 1928)

From modest beginnings, Marie Louise Fuller had no formal education in dance or academia (beyond primary school). Although she is known for her portrayal of Salome—she presented one of the first modern versions of the Salome story before the advent of Salomania,²⁹ although hers was not as successful or scandalous—as well as dancing in long swathes of veils and fabric, she was also especially talented in lighting design and projections, using them to add innovative depth and color to her performances. She is considered one of the first “free dance” performers and was one of the first American solo barefoot aesthetic dancers to enjoy a successful career in Europe.

Born in the Chicago suburb of Fullersburg, now Hinsdale, Illinois, Fuller began her theatrical career as a professional child actress. When she was a teenager, she accepted any bit part she could get in Chicago. Performance opportunities at this time were multiplying as both legitimate theater and variety shows expanded in response to an increasing demand by the American public for commercial entertainment.³⁰ Fuller’s roles, however, were limited mostly to portraying the ingenue or even boys in farce, melodrama, and burlesque shows. Between the late 1870s and early 1880s, Fuller based herself in New York, touring with a long list of theater companies, including the world-famous pageant known as Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show.³¹

Fuller began her theatrical career as a professional child actress and later choreographed and performed as a skirt dancer³² in vaudeville and circus shows. An early free dance practitioner, Fuller developed her own natural movement—based on running, turning, posing, and twisting the torso—and improvisation techniques. She never studied dance formally; she claimed that ballet depended on “torture and disfigurement.”³³ Her physical form was a bit of a paradox: portrayed as a lithe, long-limbed sylph on her promotional posters, she was, in reality, a bit chubby with a fairly plain face.³⁴

Fuller combined her choreography with silk costumes illuminated by multi-coloured lighting of her own design. Like many dancers of her time, she performed in Orientalist shows, in which she integrated Indian “nautch” influences into her performances. In 1887 in New York, she played the title role in Aladdin’s Wonderful Lamp, a pantomime adaptation of The Thousand and One Nights³⁵ which made use of projectors and other experimental stage lighting techniques that would later guide Fuller’s own solo work.³⁶

When Fuller toured the United States and in London in the 1880s and 1890s, stage dancing was not considered a respectable art form. Anthea Kraut notes that female theatrical dancers of all kinds, even ballet dancers, were considered “morally suspect.” ³⁷ Also, non-ballet dance performances were rarely presented on their own, but rather as part of a larger stage production as a divertissement. Fuller developed one of her most famous performances, the “Serpentine Dance,” as part of an 1891 play called Quack, M.D., in which she played a widow who underwent hypnosis.³⁸

When she traveled to live and perform in Europe in 1892, she made her solo debut at the Folies Bergère in Paris, but not after the shock of seeing a poster advertising an imitation performance at the very same venue.³⁹ Dance scholar Toni Bentley says that Fuller became the most imitated performer of her day.⁴⁰ In fact, the Ballets Russes found inspiration in Fuller’s work, sometimes basing their own works on earlier ones by Fuller, such as Salome.⁴¹ The host of imitators prompted Fuller to begin patenting her costumes, such as a “garment for dancers” which included a bodice and a skirt with wands attached to allow the dancer to manipulate the fabric.⁴² She also secured patents in France, the United States, and Germany for stage devices such as a mirrored room⁴³ and a projector that consisted of a rotating colored disk that would shine abstract patterns on a dancer.⁴⁴ She guarded her props and costumes very closely, only allowing a few trusted people to pack and unpack them for her performances.⁴⁵

When she was, she performed a version of Salome’s dance at the Théâtre des Arts in Paris in a costume made of 4,500 feathers, and she used 650 lamés and fifteen projectors to make the stage appear as though it were a sea of blood during the scene of John’s decapitation.⁴⁶ Her performance of La Mer in 1925, late in her career, demonstrated the apex of her use of fabric and veils in which dancers manipulated a stage-sized from underneath to make it resemble the ocean. Fuller used her signature lighting design to shine changing blue and green light on the stage, emphasizing the liquid effect.⁴⁷

Despite her initial astonishment at imposter Serpentine dancers, she quickly became the “toast of Paris with her fantastic displays of veils and lights.” She appeared at the Paris World’s Fair—the Exposition Universelle—of 1900, insisting that she perform in her very own theater, which was designed by Art Nouveau artist Henri Sauvage. Here, she inspired such artists as René Lalique and Pierre Roche.⁴⁸ She performed excerpts from her own Salome, which individually were more successful than when performed together, as Salomania had already hit France with Wilde’s play.⁴⁹ Her performance run at the Exposition launched her from an ordinary cabaret performer to a “world-renowned artist.”⁵⁰ She became a “respected member of the French artistic and cultural community,” according to music scholar Davinia Caddy. Fuller was considered to be the “living emblem of the new aesthetic, art nouveau,” and her dances “were thought to represent the image of art in the modern world.”⁵¹

Fuller traveled extensively for her performances to such places as Europe, Egypt, Morocco, and Monte Carlo.⁵² Fuller biographer Garelick says that for her French audiences, Fuller’s costumes of lilies, butterflies, and other flowing forms both invoked and inspired the Art Nouveau movement.⁵³ She was also just exotic enough for the French, being an American woman who played with Oriental themes;⁵⁴ she performed two versions of Salome in her lifetime. She also, despite eschewing the rigidity of ballet, appeared to decoratively float above the stage—as a ballerina does while en pointe—with the long rods in her sleeves extending her movement beyond her personal kinesthetic range, which also probably appealed to her French viewers.

Biographer Garelick claims that despite being linked with modern dance pioneers such as Isadora Duncan and Ruth St. Denis, Fuller’s real innovations and contributions to performance were her technical ones.⁵⁵ She also did not rely on the revelation of her body for her performances, as did Maud Allan and Mata Hari; she was a “chaste dancer” who did not try to cultivate an off-stage personality.⁵⁶ She occassionally returned to the United States, but spent her later life in Paris, where she died of pneumonia in 1928 at the age of 65. Her body was cremated and inurned at the Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris.

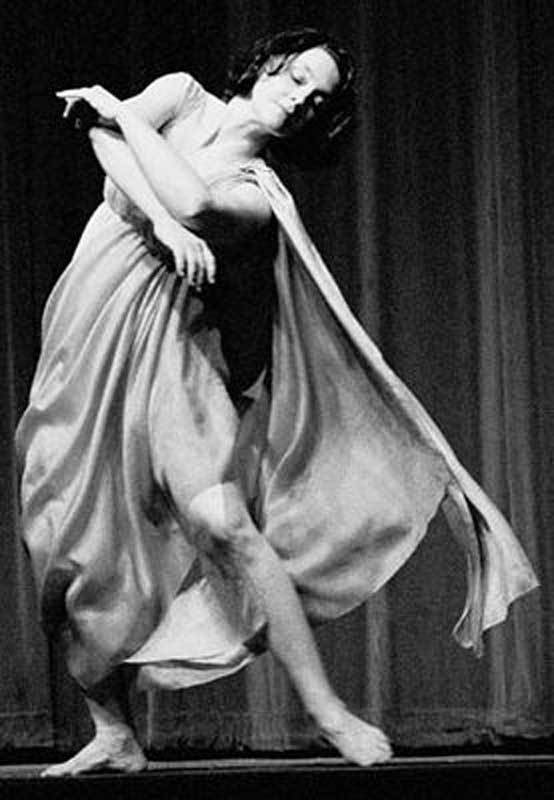

Isadora Duncan (1877 – 1927)

Born in San Francisco, California, Angela Isadora Duncan was the daughter of Joseph Charles Duncan—a banker, mining engineer, and arts connoisseur—and Mary Isadora Gray,⁵⁷ a musician and music teacher.⁵⁸ In her autobiography, she writes that her mother was very poor, and encouraged the young Isadora to use her inherent talent for dancing to earn money for the family.⁵⁹ In her writings, she frequently refers to her family’s poverty as inspiring her tenacity and drive for success. The youngest of four children, she began her career in dance at a very early age; she gave her first performance at age four, and by the time she reached six years of age, she was teaching lessons in her home and continued through her teenage years. She had no formal dance training as a child; she found inspiration in nature, the ocean, and the arts. Her father’s collection of sculptures, engravings, and other art in the Duncan family home inspired Duncan’s aesthetic: that of “beautiful ancient dresses” and the “perfect beauty of the great masterpieces.” ⁶⁰ Her mother would play music for and read poetry to her children, and Duncan became an avid reader herself, diving into the works of Charles Dickens, William Shakespeare, and Walt Whitman.⁶¹

Her parents had divorced when Duncan was still a baby, and by the time she turned twelve, she had formed an unfavorable opinion of marriage. Women at the turn of the 19th century, she felt, created “slavish” conditions for women, and she vowed that she would never marry.⁶² She remained deeply committed to the liberation of women her entire life. She wrote that the “dominant note” of her childhood was the “constant spirit of revolt against the narrowness of the society in which we lived,” a sentiment that would eventually lead her to become a Bolshevik sympathizer and move to the Soviet Union.

Her Greek aesthetic already in formation, she claimed that San Francisco was “inhospitable” to her ideas; Duncan moved to Chicago in the summer of 1895, when Duncan was eighteen; she believed it to be one of the most progressive cities in the United States.⁶³ After sending her name in “over and over again” she won an audition with Augustin Daly, who was one of the more important producers on Broadway, and he gave her a small pantomime role, and she moved to New York.⁶⁴ She claimed in a letter to Daly to be the “spiritual daughter of Walt Whitman,” and that she would, “for the children of America […] create a new dance that will express America.”⁶⁵ With Daly’s performance company, she received formal dance training with Carl Marwig, which she neglected to mention in her writings or memoirs.⁶⁶ Feeling limited by the exaggerated pantomime work availed to her in New York, she left Daly’s company and moved with her mother, sister Elizabeth, and brother Raymond to London in 1898, feeling that European audiences would be more receptive to her Greek-inspired, expressive mode of movement. There she found work performing—her mother and siblings both accompanying her by playing music and reading poetry—in the drawing rooms of society women, and drew further inspiration from the Greek vases and bas-reliefs in the British Museum,⁶⁷ as well as the works of Pre-Raphaelite artists in the National Gallery in London.⁶⁸

There she enjoyed great success and used her earnings to rent her own dance studio, developing her work and creating larger stage performances. Her brother had since left for Paris, and he “bombarded” Duncan and her mother to join him. After arriving in Paris, she spent “hours” at the Louvre, poring over the Greek vases and other galleries. She also attended the Paris Exhibition Universelle in 1900, where she first saw the works of sculptor Auguste Rodin, which continued to influence Duncan’s dance aesthetic.⁶⁹ She continued dancing in the salons of the wealthy and began a courtship with writer André Beaunier. After this courtship ended in Duncan’s heartbreak, Duncan focused her emotional energy into her dancing, seeking “the central spring of all movement […] the unity from which all diversities of movements are born.” Duncan found that ballet “taught the pupils that this spring was found in the centre of the back at the base of the spine,” which she believed made the dancers appear “artificial” and “mechanical.” Duncan’s method, in contrast, she wrote, “sought the source of the spiritual expression to flow into the channels of the body filling it with vibrating light,” which for Duncan was in the solar plexus.⁷⁰

In 1902, Loïe Fuller visited Duncan’s studio in Paris, and, after dancing for Fuller, she invited Duncan to tour with her. Duncan declared Fuller an “extraordinary genius,” after attending one of Fuller’s performances in Berlin. Duncan traveled and performed throughout Europe, finding inspiration in Fuller’s innovative performances as well as great art and architecture throughout the continent.⁷¹ She visited Greece, as well, where she was able to visit the great antiquities that had inspired her in her youth.⁷² She also met and worked with Russian theater director Constantin Stanislavsky, who first saw her dance in Moscow.⁷³ In St. Petersburg, Russia, she met and dined with Anna Pavlova, Leon Bakst, and Sergei Diagilev; she also observed classes at the Imperial Ballet School, where she saw the young dancers performing, in Duncan’s words, “torturing exercises,” standing on the “tips of their toes for hours, like so many victims of a cruel and unnecessary Inquisition.”⁷⁴ She declared herself an “enemy of ballet,” claiming that the restrictive costuming inhibited free and natural movement; she included steps such as skipping, which were not part of ballet training. She preferred to dance in bare feet and valued simplicity over spectacle.⁷⁵ She preferred to speak of dance and art through metaphor and imagery, and did not use technical language as she taught.⁷⁶

Duncan returned to Berlin and established her first school of dance in 1904, in Grunewald, Germany. There she created her dance company, the Isadorables. She taught that movement should be inspired by nature, such as “the movements of the clouds in the wind, the swaying trees, the flight of a bird, and the leaves which turn.”⁷⁷ She later opened a school in Paris, which closed during World War I. Duncan, having had a difficult time as a child in a public school in California, was passionate about education. She wrote that the thing that interested her “the most in the world [was] the education of children,” and that “all problems can be solved if one begins with the child.”⁷⁸ Duncan disliked the commercial aspects of public performance such as extensive touring, because she felt they distracted her from her real mission: the creation of beauty and the education of the young; she wrote that she wanted to start a dancing school in the United States to “train children how to live.” ⁷⁹ In 1921, her leftist sympathies took her to Russia; the Russian Government agreed to assist her in founding a dance school in Moscow.⁸⁰ Her pro-Soviet and Bolshevik tendencies eventually led to the United States government revoking her citizenship in the early 1920s.

Her love life was unconventional, especially for the time. Various letters that she had written in her lifetime suggest she was bisexual. She also had two children out of wedlock: Diedre (b. 1906), with theater designer Gordon Craig, and Patrick (b. 1910), with Paris Singer, a son of the sewing machine magnate Isaac Singer. Both children drowned when the car they were in rolled into the Seine river. In 1922 she married the Russian poet Sergei Esenin who was 18 years her junior; they separated in 1923, and he committed suicide two years later.

Duncan is now considered the philosophical founder of modern dance.⁸¹ She never taught her students choreography, believing that doing so would inhibit the development of their natural abilities. She said that she “never taught my pupils any steps,” and that she “never taught myself technique. I told [my students] to appeal to their spirit, as I did to mine.” ⁸² Although she is often grouped with the likes of Ruth St. Denis and other barefoot dancers of the early 20th century, Duncan’s repertory, recorded lectures, autobiography, and writings show that she did not take direct inspiration from the Middle East, South Asia, or East Asia.⁸³ Instead, she found inspiration in the classical worlds of ancient Greece and Rome. Duncan was the first of the modern dancers to see how effective it would be to meld her high profile, adventurous personal life with her onstage personal as a free-spirited beautify, whose costumes sometimes “accidentally” exposed her breasts.⁸⁴

Duncan’s fondness for flowing scarves played a role in her untimely death in 1927. Her silk scarf, which had been draped around her neck, became tangled in the open spoke wheels of the car in which she was a passenger and broke her neck. She was cremated, and her ashes are inurned at the columbarium at the Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris, France.

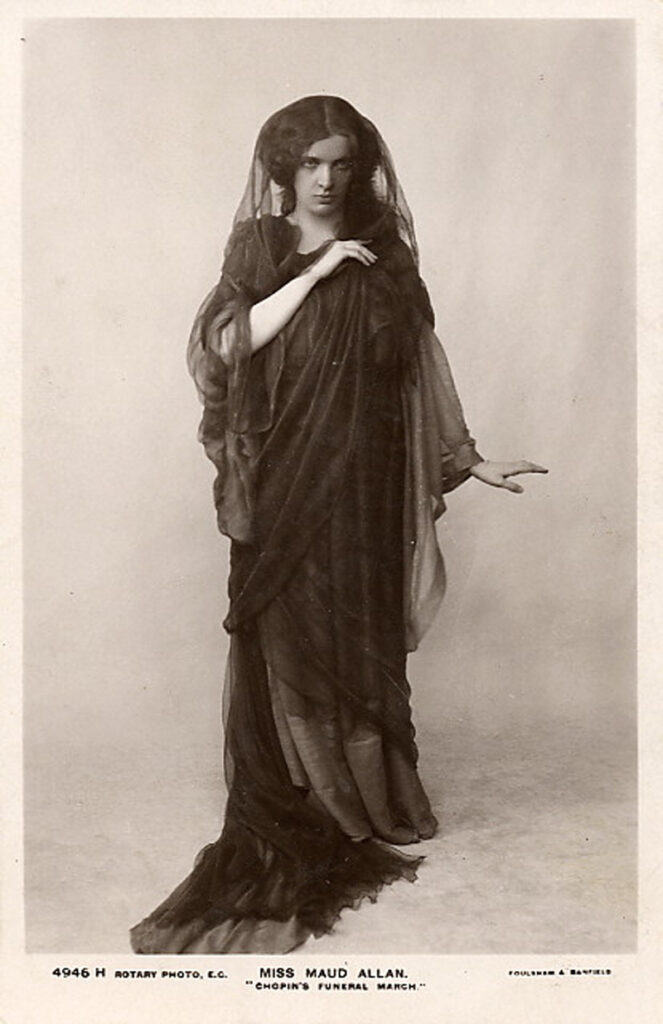

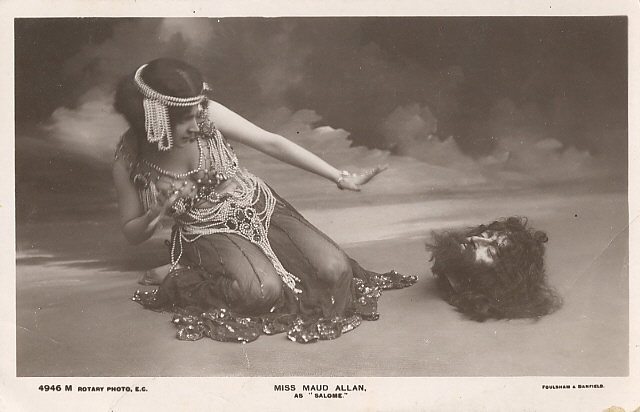

Maud Allan (1873 – 1956)

Born Beulah Maude Durrant in Toronto, Canada, sometime between 1873 and 1880, the woman later to be known as Maud Allan spent her early years in San Francisco. She left for Berlin to study piano in 1895, and shortly thereafter her brother—with whom she was quite close—was arrested, accused of brutally murdering two women in San Francisco, and after a hugely publicized trial, was found guilty and hanged in 1898.⁸⁵ The conviction of her brother caused an enormous scandal—the San Francisco Chronicle called it the “Crime of the Century”—prompting the young Beulah to change her name in an effort to distance herself from her brother’s crime. This event shaped Maud Allan’s decision to abandon music, finding an alternate means of self-expression in dance, despite having little formal dance training.

After her brother’s costly trial, her family had no more means of supporting Maud while she was in Europe, so she started a corset business and, scandalously, received a commission to illustrate a two-volume German sex manual for women, published in 1900. She also became engaged to Artur Bock, a young sculptor for whom she modeled, but eventually, she broke off the engagement.⁸⁶ She modeled as Salome for Bock, as well for Franz von Stuck’s Salome in 1906, for which she posed nude.⁸⁷

In 1900, she definitively chose dance as her preferred means of expression, but eschewed ballet, as she was too advanced in age, seeking out a new form of dance instead. Allan became interested in the kind of barefoot dancing initiated by Isadora Duncan, even though she was not a fan of Duncan herself. Scholar Judith Walkowitz argues that Allan’s realization that she would be unable to make a living through her piano studies also spurred Allan to choose a career in dance.⁸⁸ Allan attended no dance classes but rather imitated classical poses and experimented in front of a mirror. She began her public career as a dancer in 1903, at the age of 33, performing to the music of Bach, Beethoven, Schubert, Schumann, and Mendelssohn,⁸⁹ in layers of veils, which at the time was considered akin to being completely nude.⁹⁰ Later, she designed her famous Salome costume of pearls, jewels, and a bare midriff.

In 1906, Allan saw a production of Oscar Wilde’s Salome and was so inspired by it that she created her own theatrical performance, which she titled The Vision of Salome. Her version of the Salome story debuted in December 1906 in Vienna and became a touring production. The Vision of Salome made her into a star in the London theatrical season in 1907, and her success far exceeded the popularity of other barefoot dancers.⁹¹ She performed Salome’s dance not as a “dance of the seven veils,” but rather as a dream sequence in which she dances the events leading up to John’s beheading.⁹² In 1908 she gave over 250 performances in an 18-month run at the Palace Theatre in London,⁹³ which was also the very theater where Wilde’s Salome premiered with Sarah Bernhardt in the title role before Lord Chamberlain banned it in 1892.⁹⁴ Walkowitz notes that as the star of the Palace Theatre, Allan enjoyed greater success than her North American counterparts and competitors: Loïe Fuller and Isadora Duncan.⁹⁵ The New York Times wrote that “Miss Allan’s Salome Dance [had] so fired the imagination of London society” that “one of the great hostesses of the metropolis […] issued invitations to twenty or thirty ladies,” to a women-only “Maud Allan” dinner dance, and to which the guests were asked to wear Salome costumes.⁹⁶

Dance scholar Anthony Shay says that her portrayal of Salome as an “innocent victim of her mother’s scheme to execute John the Baptist rather than as an over-sexed nymphomaniac” contributed to her success.⁹⁷ Writer Lucinda Jarrett claims that her strength lay in “her ability to walk a fine line between art and pornography,” and she was one of the “few music hall stars with whom Edwardian society felt at ease.” ⁹⁸ Music scholar Caddy notes that Allan’s physical appearance contributed to future incarnations of the “vamp” with her “full lips, dark hair, blue-green eyes, pale skin, and shapely figure.” ⁹⁹ Word of her performances, as well as the appearance of “cooch” dancers at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893, spawned hundreds of imitators who appeared on the lower-class vaudeville stages throughout the United States.

In late 1909, buttressed by sensational success in England, she decided to tour with her version of the Salome story. She was not so successful outside of England, with empty theaters and bad reviews in Moscow, and bored audiences in New York City who had already seen Allan’s many imitators.¹⁰⁰ Indeed, even in London, she faced negative reviews. Caddy tells us that some equated Allan’s performances with prostitution, and “openly pornographic articles and books” described her “nude modeling and sexual activity.”¹⁰¹ Salomania had already come and gone, and Allan’s star began to fade.

Her troubles intensified in 1918 when her name was included on a list published in The Times compiled by a British politician during World War I of 47,000 British men and women who were guilty of not only “depraved and lecherous behavior” but also of being under German influence. He also published in his own journal an article, “The Cult of the Clitoris,” which implied that Allan, then appearing in her Vision of Salome, was a lesbian associate of German wartime conspirators. Allan sued the politician for libel, but lost, as the jury found him innocent of all charges. Her fame faded, and, despite continuing to perform, Allan fell into obscurity and died in Los Angeles in 1956 at the age of 84.¹⁰²

During the height of her popularity, she managed to develop a good representation in the media of her age, which distanced her performances from the “supposedly provocative dances of the East.”¹⁰³ Part of her fame could be attributed to the fact that her dances expressed the “spirit of the East,” without actually being authentic dance from the Middle East or North Africa.¹⁰⁴ Interestingly, despite being independent, probably bisexual, and transgressing the ideal of a woman as mother and homemaker, she opposed women’s suffrage, saying that women are too “emotional” and “swayed by personalities.” She did, however, believe in equal education and job opportunities for women and those who did not have men to support them.¹⁰⁵

Ruth St. Denis (1879 – 1968)

One of the most influential figures of modern dance vis-à-vis the “Orient” is arguably Ruth St. Denis. Dance historian Elizabeth Kendall argues that she began the lineage of modern dance in the United States.¹⁰⁶ Her rise to fame and ability to present herself in respectable theaters as a solo female performer as well as her integration of fantasy and mythological Oriental elements has made a lasting impression on dancers for generations to come.¹⁰⁷ Born in New Jersey as Ruth Dennis and raised on a farm, she pioneered the use of Middle Eastern and South Asian imagery, influence, and mythology in modern dance. As a child, her mother taught her dance exercises by François Delsarte, a French composer, who was also an acting and singing coach who developed a system of movements and breathing for performance. The Delsarte system was a codification of human movement and gesture, as well as a “spiritual labeling of every part of the body according to different zones,” such as Head, Heart, and Lower Limbs, which corresponded to Mind, Soul, and Life. This system, which by the 1890s had gained popularity amongst “fashionable women eager to explore the frontiers of self-awareness,” greatly influenced St. Denis’ personal approach to movement and aesthetics.¹⁰⁸

Her path to becoming a dancer was set early. As a child, she was greatly inspired by seeing P.T. Barnum’s circus in 1886 when she was seven years old, and in 1892 seeing Egypt Through the Centuries, a grand performance spectacle at the Palisades Amusement Park.¹⁰⁹ Because of her early training in the Delsarte method, Ruth was a gifted dancer as a child. In 1894 she worked as a skirt dancer at the Worth’s Family Theater and Museum performing in the vaudeville style. She then toured with David Belasco’s production of Madame DuBarry in 1904, and it was then that she saw an advertisement poster for Egyptian Deities cigarettes, featuring an image of the ancient Egyptian goddess Isis. So moved and inspired by this image, she sought to create dances inspired by Eastern imagery and mysticism. She wrote that the image “became the expression of all the somber mystery and beauty of Egypt,” she “knew that my destiny as a dancer had sprung alive at that moment.”¹¹⁰ She then began reading about Egypt as much as she could. When the Belasco touring company returned to its home base in New York, she visited a “whole village of Hindus” at Coney Island, which was as close as she could get at the time to Egypt. She temporarily shifted her artistic interest to India.¹¹¹

In 1905, she left Belasco’s company to become a solo performer and created her first piece, Radha, inspired by her readings of Hindu mythology. Radha was first performed at a vaudeville house in New York City, with Ruth appearing between acts by a pugilist and a group of trained monkeys. A New York socialite and oriental enthusiast saw the show and secured a private matinee of the show for her society friends, launching St. Denis onto the high art circuit.¹¹² Mark Wheeler notes that even though Americans had been fascinated by the “Orient” for several decades before St. Denis began her solo career, St. Denis brought her vision of the Orient to the stage in seriousness and depth lacking in the vaudeville shows of her time.¹¹³ She changed her name when her mother, also a performer but also quite religious, remembered Belasco’s nickname for Ruth—Saint Dennis—and the name stuck, with the missing “n.”¹¹⁴

In 1906, accompanied by her mother, St. Denis headed to Europe, where a host of other barefoot dancers had already found fame, such as Maud Allan, Loïe Fuller, and Isadora Duncan. She stayed there for two years, performing in Berlin, Paris, and London, as the style of female solo interpretive dancing, especially that inspired by the “East,” grew increasingly popular.¹¹⁵ She and her mother returned to the United States in 1909, despite an offer by the citizens of Weimar to build her a theater under the stipulation that she stay another five years.¹¹⁶

In 1911, when the fad of Salome’s and Oriental-styled soloists began to wane and a new craze—ragtime—gained popularity, St. Denis’ career as a soloist began to founder. At this time, however, she saw a performance by the young dancer Ted Shawn—fourteen years her younger—who later became her artistic partner and husband. Interestingly, Ted Shawn had been a long-time admirer of St. Denis and her work before the two met.¹¹⁷ The pair opened the Denishawn School of Dance in 1915 in Los Angeles, where they taught a blend of ballet, yoga, and free-form exercises that would later become the foundation for modern dance technique; students always practiced barefoot. The school helped fund the couples new company, the Denishawn Dancers, which toured internationally.¹¹⁸ The company appeared as the headliners of the Ziegfield Follies of 1927.¹¹⁹

Mark Wheeler notes that the school’s instruction of “Oriental” dance styles “ensured that the Orient would figure in the development of modern dance.”¹²⁰ With the invention of moving pictures, Hollywood producers found the Denishawn combination of vaudeville aesthetics and formal dance training perfect for their interpretations of the dances of the “Orient.”¹²¹ Members of the school appeared in the Babylonian scenes of D.W. Griffith’s grand production, Intolerance, in 1916, as St. Denis and Ted Shawn coached them on the set.¹²² Martha Graham, Doris Humphrey, film star Louise Brooks, along many other influential performers studied under their tutelage.

In the early 1930s, St. Denis and Shawn ended their personal and professional partnership. Dance scholar Thom Hecht notes that the last rehearsal of Denishawn at Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival in Becket, Massachusetts, in 1931 heralded the end of an era as both the Denishawn school and the dance company ceased to exist.¹²³ Never swayed from her work, however, St. Denis founded the dance program at Adelphi University in 1938 in New York, which is considered to be one of the first ever dance departments at a United States university¹²⁴.¹²⁵ She continued to perform, lecture, and teach well into the 1960s, until 1968, when she died of a heart attack in Los Angeles at the age of 89.¹²⁶

Although her dances must have appeared authentic in the eyes of her audiences, they were never true representations of regional dances; it’s unlikely that she had the opportunity to study Indian, Middle Eastern, or other ethnic dance forms in depth. She avoided the “obvious sexuality of the pelvis and focused on movements of the upper body,”¹²⁷ and it is doubtful that her audiences even knew the authentic or national characteristics of these regional dances.¹²⁸ St. Denis herself said, “All I had to do was take the best poses [that she had seen in books and museums], the most meaningful ones, and set those poses dancing.”¹²⁹ ¹³⁰ She did, however, according to dance scholars Anthony Shay and Barbara Sellers-Young, see herself as a “a cultural ambassador of the East.”¹³¹ Scholar Sally Banes notes that St. Denis’ dances were also considered more respectable than many of her contemporaries who also performed Eastern-inspired interpretive dances because she made use of spiritual and religious overtones in performances that would otherwise have been “unambiguously erotic choreographies.”¹³²

St. Denis’ vision of a “spiritually mysterious orient”¹³³ continues to influence practitioners of Oriental dance, as seen in Dr. Laurel Victoria Gray’s 2003 production of Egypta, Dalia Carella’s In Search of a Goddess (an artistic exploration of St. Denis’ life and work) in the early 2000s, and the most recent aesthetics of the tribal fusion stylization (2008 – 2015).

La Meri (1899 – 1988)

La Meri, a contemporary and also a student of St. Denis, was one of the first American dancers of the twentieth century to actively pursue a study of foreign dance traditions.¹³⁴ Dance writer Walter Sorrell described her as “the indisputed queen of ethnic dance.”¹³⁵

She was born Russell Meriwether Hughes, named after her father, and grew up in San Antonio, Texas. She began her dance training there, studying ballet, Spanish, and Mexican dance forms. She began her professional career in the 1920s and between then and 1939, toured many parts of the world¹³⁶ performing in vaudeville, motion-picture houses, nightclubs, and later, theater productions. She acted, sang, and played violin, but it was her dancing that eventually gained her feature billing.¹³⁷ By the time she was twenty-one, she and her mother had traveled widely, including trips to New York City and Europe. She studied hula in Hawaii, and in New York, and studied modern dance and ballet as she auditioned for various theatrical roles.¹³⁸ Like St. Denis, she read everything she could about world dance forms and was a lifelong student with a passion for both “intellectual as well as experiential study.”¹³⁹

Although she studied various world and ethnic dance forms, La Meri’s interest in Oriental dances began after attending a performance of Ruth St. Denis’ Indian-inspired Dance of the Five Senses by the Denishawn company “sometime around 1915.”¹⁴⁰ At first, her explorations of Oriental dance did not distinguish between regions or dance traditions, drawing on Orientalist tropes and blending East Indian, Chinese, Japanese, and Javanese dances in performances, which she presented to Western music.¹⁴¹ She received her big break in December 1925, when she audienced for “an old-fashioned impresario,” Guido Carreras, who had managed the careers of Nijinsky and Pavlova, as well as other famous clients; the two married in 1937.¹⁴² With his guidance, La Meri was an international star throughout the twenties and thirties, studying and performing on four continents. In 1929, she traveled to Fez, Morocco, and studied dance with a woman known only as Fatma (sometimes spelled “Fatima”), who performed in the court of Moulay Yusuf who had become sultan in 1909.¹⁴³

While living in New York, she decided to introduce American audiences to ethnic dance, with the encouragement of Ruth St. Denis. La Meri worked with St. Denis from 1940 and remained a lifelong friend of St. Denis. She even taught what she had learned from authentic ethnic dancers to St. Denis as La Meri attempted to “learn from St. Denis that unfathomable charisma that dancers like Ruth St. Denis and Isadora Duncan brought to the stage.”¹⁴⁴ In 1940, she reluctantly opened the School of Natya with St. Denis, which was devoted to Indian Dance, and formed The Five Natyas, her first performing company. She presented her first major work, Krishna Gopala in 1940, with St. Denis as a guest artist.¹⁴⁵ She also began writing extensively on ethnic dance. Her book Spanish Dancing, published in 1948, was considered at the time to be the definitive text on Spanish dance.¹⁴⁶

La Meri lived in Europe for three years, first in Paris and then in Italy, but her worldwide touring came to an end during World War II. The Fascists seized and raided her Italian home overlooking the Mediterranean, taking her books, records, costumes and personal belongings. She then returned to New York, planning to tour the United States, but wartime rationing of gasoline and tires prevented her from doing so.¹⁴⁷

La Meri’s marriage ended in 1944 when she was 46 years old, allowing her to embark on a new life and career path. After Ruth St. Denis returned to California, La Meri opened her own dance company and school in 1945, called the Ethnologic Dance Center; expanded the instruction beyond Indian dance; and performed and presented concert programs of young ethnic dancers from around the world.¹⁴⁸ This school expanded to offer a four-year program as well as graduate-level courses; La Meri was forced to close the center in 1956 because of financial troubles.¹⁴⁹

In 1960, La Meri felt frustrated and tired of the lack of audiences for ethnic dance, the difficulty of producing concerts, and the infighting in the ethnic dance community, so she and her sister moved to Cape Cod, Massachusetts. She continued to teach at Ted Shawn’s Jacob’s Pillow Dance Theater in the summers as well as workshops throughout the United States. She also continued writing on dance, publishing several books. After planning a memorial performance in honor of her sister who passed away in 1965, she was bitten by the dance bug once again. She then created Ethnic Dance Arts, Inc., in Cape Cod, and presented summer festivals of ethnic dance.¹⁵⁰ In 1972, La Meri received the Capezio Award.¹⁵¹

However, by 1980, she discovered that a trusted employee of Ethnic Dance Arts, Inc., had stolen a large sum of money in 1975, severely damaging the organization. With her students retiring or leaving to begin families, the organization suffered further, and La Meri returned to her home city of San Antonio where she served as a senior editor and writer for Ibrahim Farrah’s magazine Arabesque. In 1988 she died of kidney failure at the age of 89.¹⁵²

La Meri was one of the first champions of ethnic dance study in the United States, and she contributed significantly to dance studies and education through her performances and many books that she had written on world dance.¹⁵³ Dance scholar Anthony Shay says that she differed from her predecessors because she had a genuine interest in learning “authentic materials from native dancers.”¹⁵⁴ She detested the distorted image of ethnic dance in the Western public eye, and blamed vaudeville and later burlesque for the low-class and vulgar representations of Indian and Middle Eastern dance as well as Hawaiian hula.¹⁵⁵ Being a little younger than Ruth St. Denis and her contemporaries, La Meri can be considered a direct descendent of the pioneer “exotic dancers” (“exotic” here meaning “inspired by the Orient”), heralding a new generation of dancers interested in integrating elements of the “Orient” into their performance and practice. Her study also can be viewed as a “bridge” between the interpretive performanes of Ruth St. Denis and the “more authentic manner of learning the various foreign dance genres of succeeding generations of dancers.”¹⁵⁶

However, like St. Denis, La Meri searched for the “essentialist and spiritual ‘Orient.’” More often than not, she used Western music in her performances, rather than authentic music, because she felt that doing so “made good theater” because the “average audience is not conditioned to the sound of Oriental music.”¹⁵⁷ For example, she used Indian movement to interpret the music of J.S. Bach’s in her Bach Bharata, and Rimsky-Korsakov’s classic symphony for her own Schéhérazade.¹⁵⁸

She had dedicated her life to preserving and teaching ethnic dance, but she also insisted that the dances must be allowed to change and “take new places in the world.” La Meri insisted that ethnic dance remain a living, rather than an “archeological,” exercise. La Meri biographer Patricia Taylor says that La Meri “understood the delicate balance between the need to preserve ethnic dance and the need to present it in such a way that Western audiences could enjoy it.” La Meri also felt that it was “not necessary to have originated from a certain country to correctly perform the dances of that country.”¹⁵⁹

The content from this post is excerpted from The Salimpour School of Belly Dance Compendium. Volume 1: Beyond Jamila’s Articles. published by Suhaila International in 2015. This Compendium is an introduction to several topics raised in Jamila’s Article Book.

If you would like to make a citation for this article, we suggest the following format: Keyes, A. (2023). Oriental Imagery and the Dawn of Modern Dance. Salimpour School. Retrieved insert retrieval date, from https://suhaila.com/oriental-imagery-and-the-dawn-of-modern-dance

1 American Belly Dance and the Invention of the New Exotic – Masters Thesis, 35

2 Alexandra Kolb, “Mata Hari’s Dance in the Context of Femininity and Exoticism,” Mandrágora 15:15 (2009): 59.

3 Stone, “Reverse Imagery,” 253.

4 Anthony Shay, Dancing Across Borders, The American Fascination with Exotic Dance Forms (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2008), 60.

5 Barbara Sellers-Young, introduction to Belly Dance Around the World: New Communities, Performance and Identity, ed. Caitlin E. McDonald and Barbara Sellers-Young (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2013), 9.

6 Elizabeth Kendall, Where She Danced: The Birth of American Art-Dance (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984), 8.

7 Caddy, “Variations,” 38.

8 Shay, Dancing Across Borders, 56.

9 Anthea Kraut, “White Womanhood, Property Rights, and the Campaign for Choreographic Copyright: Loïe Fuller’s Serpentine Dance,” Dance Research Journal 41:3 (Summer 2011), 7.

10 Shay, Dancing Across Borders, 14.

11 Bentley, Sisters of Salome, 93.

12 Ibid., 94.

13 Ibid., 99.

14 Ibid., 99.

15 Kolb, “Mata Hari’s Dance,” 58.

16 Bentley, Sisters of Salome, 100.

17 Kolb, “Mata Hari’s Dance,” 60.

18 Ibid., 58.

19 Quoted in Bentley, Sisters of Salome, 99.

20 Kolb, “Mata Hari’s Dance,” 63.

21 Ibid., 58-9.

22 Ibid., 60.

23 Bentley, Sisters of Salome, 105.

24 Ibid., 106.

25 Ibid., 108.

26 Ibid., 111.

27 Ibid., 89.

28 Kolb, “Mata Hari’s Dance,” 66.

29 Bentley, Sisters of Salome, 44.

30 Richard Nelson Current and Marcia Ewing Current, Loie Fuller: Goddess of Light (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1997), excerpt at http://www.nytimes.com/books/first/c/current-loie.html.

31 Rhonda K. Garelick, Electric Salome (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007), 23-24.

32 Skirt dancing, which originated in England, was a blend of clogging and French can-can and was popular on vaudeville and dime museum stages throughout England and the United States. Dancers would wear long flowing skirts, often up to 100 yards at the hem, and performed under colored lights to emphasize the movement of the fabric. See Horrible Prettiness for more about skirt dancing.

33 Garelick, Electric Salome, 120.

34 Current, Loie Fuller.

35 Kraut, “White Womanhood,” 11.

36 Garelick, Electric Salome, 26-28.

37 Kraut, “White Womanhood,” 8.

38 Ibid.

39 Ibid., 14.

40 Bentley, Sisters of Salome, 44.

41 “Isis Wings,” now a popular prop used by contemporary belly dancers, likely have their origins in the voluminous fabric of Fuller’s costumes. They have no known connection to dance in the Middle East.

42 Garelick, Electric Salome, 124.

43 Kraut, “White Womanhood,” 19.

44 Garelick, Electric Salome, 42.

45 Elizabeth Artemis Mourat, “The Veil And Oriental Dance,” accessed December 12, 2013, http://web.archive.org/web/20080311235151/http://www.shira.net/veilhistory.htm.

46 Bentley, Sisters of Salome, 44.

47 Garelick, Electric Salome, 183.

48 Ibid., 81.

49 Ibid., 90.

50 Ibid., 67.

51 Caddy, “Variations,” 41.

52 Mourat, “The Veil.”

53 Garelick, Electric Salome, 40.

54 Ibid., 109.

55 Ibid., 157.

56 Ibid., 161.

57 For a complete and insightful biography on Isadora Duncan, see Peter Kurth, Isadora Duncan: A Life (New York: Little, Brown, and Co., 2001).

58 Isadora Duncan, My Life (New York: Boni and Liveright, 1927), 10.

59 Isadora Duncan and Franklin Rosemont, Isadora Speaks (San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1981), 24.

60 Ibid., 25.

61 Whitman is considered by many to be one of the great American poets. Often called the father of free verse, his poetry blended transcendentalism and realism, with a great love for humanity and nature. His quintessentially American style influenced many authors and artists, such as members of the Beat movement of the 1950s and anti-war poets of the 1960s.

62 Duncan, My Life, 17.

63 Kurth, Isadora Duncan, 34.

64 Ibid., 38.

65 Duncan, My Life, 31.

66 Kurth, Isadora Duncan, 45.

67 Duncan quoted in Ibid., 57-8; Duncan, My Life, 53.

68 Duncan, My Life, 62.

69 Ibid., 67-9.

70 Ibid., 75.

71 Ibid., 95.

72 Ibid., 123.

73 Kurth, Isadora Duncan, 175.

74 Duncan, My Life, 164, 166.

75 Franklin Rosemont, introduction to Isadora Speaks (San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1981), x.

76 Kendall, Where She Danced, 135.

77 Duncan, My Life, 176.

78 Duncan, Isadora Speaks, 55.

79 Ibid., 54.

80 Duncan, My Life, 357.

81 Mark Wheeler, “The East/West Dialect in Modern Dance,” in Mind and Body: East Meets West, ed. Seymore Kleinman (Champaign, Illinois: Human Kinetics Publishers, Inc., 1986), 121.

82 Duncan, Isadora Speaks, 58.

83 Wheeler, “The East/West Dialect,” 121.

84 Garelick, Electric Salome, 159.

85 Felix Cherniavsky, Maud Allan and Her Art (Toronto: Dance Collection Danse Press/es, 1998), book excerpt, accessed December 18, 2013, http://www.dcd.ca/catalogue/maudallan.html.

86 Bentley, Sisters of Salome, 55.

87 Udo Kultermann, “The ‘Dance of the Seven Veils’,” Artibus et Historiae 27:53 (2006): 200.

88 Judith R. Walkowitz, “The ‘Vision of Salome’: Cosmopolitanism and Erotic dancing in Central London,” American Historical Review, 108:2 (2003): 342.

89 Kendall, Where She Danced, 67.

90 Bentley, Sisters of Salome, 58.

91 Deagon, “The Dance of the Seven Veils,” 250.

92 Walkowitz, “The ‘Vision of Salome’,” 352.

93 Amy Koritz, “Dancing the Orient for England: Maud Allan’s ‘The Vision of Salome’,” Theatre Journal 46:1 (1994): 63.

94 Bentley, Sisters of Salome, 65.

95 Walkowitz, “The ‘Vision of Salome’,” 350.

96 Quoted in Caddy, “Variations,” 51.

97 Shay, Dancing Across Borders, 60.

98 Jarrett, Stripping in Time, 88, 93.

99 Caddy, “Variations,” 52.

100 Bentley, Sisters of Salome, 73.

101 Caddy, “Variations on the Dance of the Seven Veils,” 52.

102 Bentley, Sisters of Salome, 71, 80, 83.

103 Koritz, “Dancing the Orient for England,” 69.

104 Ibid., 70.

105 Ibid., 74.

106 Kendall, Where She Danced, 12.

107 Jane Desmond, “Dancing Out the Difference: Cultural Imperialism and Ruth St. Denis’s Radha of 1906,” in Moving History/Dancing Cultures: A Dance History Reader, ed. Ann Dils and Ann Cooper Albright (Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press, 2001), 262.

108 Kendall, Where She Danced, 24.

109 Ibid., 27.

110 Ruth St. Denis, An Unfinished Life (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1939), 52-3.

111 Kendall, Where She Danced, 50.

112 Desmond, “Dancing Out the Difference,” 262.

113 Wheeler, “The East/West Dialect,” 121.

114 Kendall, Where She Danced, 52.

115 Ibid., 55.

116 Ibid., 69.

117 Ibid., 112.

118 Thom Hecht, “Ruth St. Denis (1879-1968): America’s Divine Dancer,” Dance Heritage Coalition, accessed December 28, 2014, 2, accessed December 30, 2014, http://www.danceheritage.org/treasures/stdenis_essay_hecht.pdf.

119 Wheeler, “The East/West Dialect,” 122.

120 Ibid., 121.

121 Kendall, Where She Danced, 131.

122 Ibid., 143.

123 Hecht, “Ruth St. Denis,” 2.

124 The Department of Dance at Mills College in Oakland, California, was also formed in the same year.

125 Ibid.

126 Ibid., 3.

127 Shay and Sellers-Young, introduction, 7.

128 Stone, “Reverse Imagery,” 253.

129 Suhaila Salimpour approached one of her early choreographies, “Karnak,” in a similar manner, inspired by the Art Deco work of Erté.

130 Quoted in Shay, Dancing Across Borders, 70.

131 Shay and Sellers-Young, introduction, 7.

132 Quoted in Kolb, “Mata Hari’s Dance,” 60.

133 Quoted in Shay and Sellers-Young, introduction, 7.

134 Jennifer Lynn Haynes-Clark, “American Belly Dance and the Invention of the New Exotic” (Masters Thesis, Portland State University, 2010), 36.

135 Quoted in Jennifer Dunning, “La Meri, 89, a Dancer, Teacher and Specialist in Ethnic Repertory,” New York Times, January 21, 1988, accessed December 18, 2013, http://www.nytimes.com/1988/01/21/obituaries/la-meri-89-a-dancer-teacher-and-specialist-in-ethnic-repertory.html.

136 Nancy Lee Rutyer, “La Meri and Middle Eastern Dance,” in Belly Dance: Orientalism, Transnationalism & Harem Fantasy, ed. Anthony Shay and Barbara Sellers-Young (Costa Mesa, California: Mazda Publishers), 208.

137 Patricia Taylor, “La Meri: A Life Dedicated to Ethnic Dance,” Habibi 16:3 (1997), accessed December 23, 2014, http://thebestofhabibi.com/vol-16-no-3-fall-1997/987-2/.

138 Taylor, “La Meri.”

139 Rutyer, “La Meri,” 212.

140 Ibid., 209.

141 Ibid., 210.

142 Taylor, “La Meri.”

143 Rutyer, “La Meri,” 211.

144 Shay, Dancing Across Borders, 70.

145 Dunning, “La Meri.”

146 Ibid., and La Meri (Russell Meriwether Hughes), Spanish Dancing (New York: A.S. Barnes, 1948).

147 Taylor, “La Meri.”

148 Ibid.

149 Adam Lahm, “Grand Lady of Ethnic Dance: La Meri (Part I),” Arabesque 4:4 (Nov-Dec 1978), 9.

150 Taylor, “La Meri.”

151 Dunning, “La Meri.”

152 Taylor, “La Meri.”

153 Rutyer, “La Meri,” 219.

154 Shay, Dancing Across Borders, 70.

155 Taylor, “La Meri.”

156 Shay, Dancing Across Borders, 70.

157 Quoted in Shay, Dancing Across Borders, 72.

158 Taylor, “La Meri.”

159 Ibid.