The establishment of national folkloric¹ dance companies in Egypt marks a significant moment in the evolution, perception, and practice of Oriental dance. The two most well-known folkloric dance companies of Egypt—The Reda Troupe and the National Folkloric Troupe (in Arabic, al-Firqat al-Qawmiyyat al-Funun ash-Sha’biyya)—have shaped the development of Oriental dance in the Middle East and Europe and the United States. These dance companies created a kind of “invented tradition,” taking indigenous dance forms and sanitizing them for the stage, transforming them into respectable and artistic choreographies. Some dances, such as Mahmoud Reda’s “Melaya Leff,” were pure theatrical creations, based not on authentic ethnic dance movement, but rather in a character or archetype. These folkloric dance companies created, as dance scholar Anthony Shay says, “modernist interpretations of what [the choreographers thought] Egyptian culture should be.”² Dancers who trained and performed with these companies have gone on to influential and lucrative careers as soloists in their own right and/or as choreographers for solo Oriental dancers.

We will now look at some of the most influential figures in the folkloric dance movement and how they changed the face of Oriental dance.

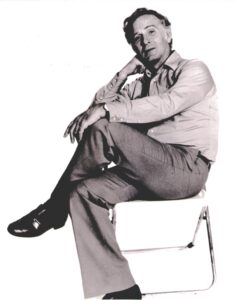

Mahmoud Reda (1930 – )

Mahmoud Reda was born in Cairo on March 18, 1930, the eighth of ten children. Influenced by his older brother Ali, a dancer himself, as well as by films starring American actors and dancers Gene Kelly and Fred Astaire, Reda became interested in dance. He took formal ballet classes, which in Egypt was not considered effeminate as it often is in the West, rather it was considered a high art and a legacy of colonialism. He originally trained as a gymnast, representing Egypt in the 1952 Summer Olympics. He joined a South American dance troupe after graduating from Cairo University and toured Europe. When he returned, he aimed to begin his own dance company and joined the Heliolido Club—a middle-class sports club in a suburb of Cairo\’s Heliopolis—in Cairo where he met Anglo-Egyptian dancer Farida Fahmy, who became his dancing partner. Reda choreographed his first work commissioned by the Egyptian government in 1954 and traveled to Moscow with the troupe that performed it. In the 1950s, dancers from the Moiseyev Dance Company of the Soviet Union were sent to Egypt to “advise” the Firqat al-Qawmiyya.³ Reda, along with his brother, Ali, turned this company into the Reda Troupe in 1959. In an interview with Anthony Shay, Reda says that he “never thought of Egyptian folklore,” even though he and his brother had a “passion for dance.” It wasn’t until Reda auditioned for an Argentine company that was performing in Cairo that Reda asked himself, “Why am I doing Argentine dance? Why not Egyptian?” Initially, the Egyptian government offered no financial support or otherwise to the Reda brothers, because, “the reputation of dance in Egypt was terrible and associated with prostitution.”⁴ After appearing in a film⁵ directed by Ali Reda, and receiving accolades from the Egyptian elite, the Egyptian Ministry of Culture decided to sponsor Reda\’s new dance company, the Reda Troupe, in 1961, incorporating it into the government.

Mahmoud Reda is credited with bringing the many folkloric and indigenous dances of Egypt to the stage, modifying them for the theater setting. Neither Western dances nor pure folkloric dances were acceptable in mid-20th-century Egypt; Egyptians perceived Western dances as vestiges of oppressive colonial influence, and indigenous folkdance was often seen as too vulgar or low class. The Reda Troupe was also able to break through the stigma and prejudice against dancers in Egypt through Farida Fahmy’s social connections, and Cairo society quickly deemed their performances acceptable. Reda himself said in an interview with Anthony Shay, “The reputation of dance [in Egypt] was terrible. We decided to avoid the strong movements of the belly and hips, and we covered the dancers.”⁶ Reda also bolstered the image of the dancer by using choreographed groups rather than improvisational soloists, which helped distance his choreographies from the stigma of the belly dancer.⁷ Shay claims that Reda consciously and specifically attempted to erase the equation of dancer, male or female, with prostitution, by erasing or altering any movements he perceived as overtly sexual.

Like many individuals of his time, Reda was not interested in reproducing authentic dance traditions on stage. They had to be remade for the approval of the new postcolonial elite;⁸ indeed, Shay notes that Reda “felt compelled to create a new and hybrid genre of dance […] to attract audiences from the elite classes whose support and approval he sought for the success of the fledgling company.”⁹ Reda’s long-time dance partner Farida Fahmy notes that Reda’s goal was to develop “a new theater dance form rather than transplanting dances from their local setting onto the stage.” She also says that Reda’s choreographic works “were never direct imitations or accurate reconstructions,” but rather they were Reda’s “own vision of the movement qualities of the Egyptians.”¹⁰ Oriental dancers continue to perform the stylizations and “folkdance” styles created and reinterpreted by Mahmoud Reda, and these dances are often considered “traditional” Oriental dance. However, it is, as Shay notes, an “invented tradition.”

In addition, Mahmoud Reda bridged the gap between indigenous movement and choreographed performance. While he did not depend on accurately reproducing traditional Egyptian dances, he did not just present Western dance forms costumed in Egyptian textiles.¹¹ He also imagined dance traditions for different regions in Egypt, such as the Nile Delta and the Suez Canal. Reda said, “The (male) fellahin of the Delta had no distinct dance tradition, so I created one. I did not want to leave the region without a dance, so I formed a style from everyday movements.” ¹² Dance ethnologists and anthropologists still find it incredibly difficult to uncover dance traditions in these regions today as the indigenous people there are resistant to sharing them with outsiders.¹³ Reda also famously invented dance styles, such as the Melaya Leff—a character dance using the melaya, a large black modesty shawl worn by women, especially in Alexandria —and the “Sugar Doll Dance”—based on a confection served at local folk festivals that Egyptians could relate to in their childhood memories. ¹⁴

In 1972, Reda stepped down as the principle dancer of the troupe but continued to choreograph and direct. By this time, the troupe had grown to one hundred and fifty dancers (from an initial group of twelve dancers and twelve musicians), musicians, and stage crew. Under Reda’s direction, the Reda Troupe went on five international tours, performing for world leaders and even at Carnegie Hall. In 1983, Farida Fahmy retired from dance and left the troupe. In 1990, Reda retired as director of the Reda Troupe. The company exists today in name only, but it has inspired the creation of regional, university, and community folkdance groups all over Egypt. The Reda Troupe has also inspired the formation of similar folkloric companies in Lebanon, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and other Arab countries. ¹⁵ Reda continues to teach and tour throughout the world, even in his 80th decade. ¹⁶

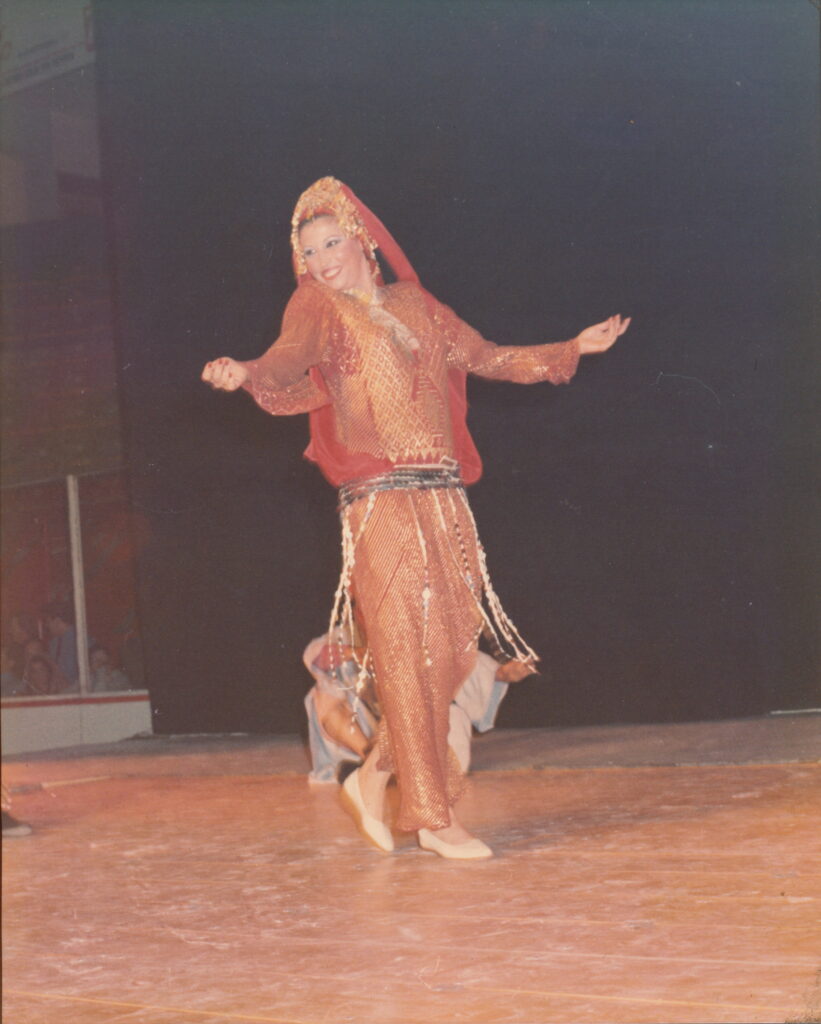

Farida Fahmy

Farida, born Melda, was the daughter of an Egyptian university professor and English mother, a graduate of the elite English School and Cairo University. Her middle/upper-class background and upbringing gave her an advantage as a performer, especially as a female dancer. In addition, her central role in the folkloric Reda Troupe also boosted her image in the Egyptian eye, and she became one of the country’s most beloved dance performers.

As a teenager, Farida attended the English school that had been established for the children of the small, elite community of Anglo-Egyptians and others. The young Melda, as she was known as a child, frequented the Heliolido Club. She and other children participated in performances that included folk dance, and it was here that she met Mahmoud Reda, who was then a member of the club’s gymnastics team. In 1957, they traveled together to a folkdance festival in the Soviet Union to perform as part of the Egyptian team. Her father never discouraged her involvement and encouraged her to represent Egyptian dance and culture to a wider world audience. ¹⁷

Farida inadvertently challenged the existing image of the female dancer in the Egyptian, and wider Arab, consciousness. She was looked upon as a “daughter or a sister, happy and wholesome, extroverted but modest, talented but not an exhibitionist, a sweet Egyptian girl a true daughter of the country.” Her dancing was viewed as part of a troupe celebrating Egyptian life and culture, and not as “a woman dancing alone for dubious purposes.” ¹⁸ Anthony Shay notes that her “brief career was built on her image as an upper-class individual who […] challenged the old disreputable image of the belly dancer as prostitute,” and that “only a woman of the upper classes could achieve an honorable reputation as a dancer, the lowest possible social category in Egypt.” ¹⁹ Indeed, Farida received several national awards from Arab leaders during her career. In 1967 Farida was decorated by Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser with the Order of Arts and Sciences for services rendered to the state, in 1956 by King Hussein of Jordan with the Star of Jordan, and in 1973 by President Habib Bourguiba of Tunisia. ²⁰

After appearing with the Reda Troupe for several decades, Farida ended her dance career in 1983. She continued her academic studies, earning her Master of Arts in Dance Ethnology at the University of California, Los Angeles. In 2000, she returned to the dance circuit, giving classes and workshops, and traveling extensively to Europe, the United States, and South America. ²¹

Raqia Hassan

Born in Cairo, Raqia started dancing at the age of four. She joined the Reda Troupe when she was 16, and a year later she became one of the first principal solo dancers in the company. Unlike many of her predecessors, she says that her family never discouraged her from dancing, even as a young teenager. In the early 2000s, she created the annual Ahlan Wa Sahlan festival in Egypt, the only dance event of its kind in the Middle East. She continues to produce it, even after Egypt’s revolution and the growing legal and social restrictions on public dancing in Egypt. Madam Raqia, as she is known, through her festival and worldwide instruction, has been credited with keeping Oriental dance alive in Egypt and around the world. Margo Abdo O’Dell says that Raqia Hassan is a purist of sorts, and believes that dance fusion “distorts the truth about Oriental” dance.²² She has trained some of the most famous contemporary dancers in the Middle East such as Azza Sharif, Dina, Dandash, and Randa Kamal, and travels to teach workshops to countless dancers around the world. ²³

Faten Salama

Faten Salama is best known for her work as a member of the Egyptian National Folkloric Troupe, also known by its Arabic name, Firqat al-Qawmiyya. The National Folkloric Troupe was founded in 1961 under the direction of Boris Ramazin, a Soviet dancer sent to Egypt to create a dance company in the image of the Moiseyev, but with an “Egyptian flavor.” ²⁴ When Faten was 11, she was selected to attend Egypt’s first-ever national folkloric dance school for children in preparation for her matriculation into the National Folkloric Troupe. Like many other dancers before her, her parents disapproved of her dancing, but agreed with the stipulation that if her academic grades suffered, she would no longer be allowed to dance.

Faten kept her promise to her parents, and after school joined the National Folkloric Troupe, traveling the world to entertain heads of state, ambassadors, and royalty. She also earned a Bachelor of Science Degree in French Literature at Ein Shams University. When she was 22, she married Shawki Naim, the National Folkloric Troupe’s choreographer, and they formed their own performance company. The Egyptian Embassy in Washington, DC, invited their new group to perform, which resulted in an East Coast tour of the United States. When in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the troupe conducted its first workshop with Nagwa Said and Jamila Salimpour. Now living in northern Virginia, she continues to hold weekly classes and workshops in the Washington, DC, area. ²⁵

Muhammad Khalil (1946 – 2005)

Muhammad Khalil was a principle dancer in the National Folkloric Troupe, joining the company in 1963 after graduating from Cairo’s Higher Institute for Theatrical Arts, Acting, and Direction. In 1976 he was appointed General Supervisor of the Musical Theater of Egypt; three years later became the director, and eventually, the general director, a position he held until 1992.²⁶ In addition to these positions, Mohammed Khalil has choreographed over 350 dances for Arab Television networks, as well as dances for the National Folkloric Troupe, which has given over 5,000 international performances. ²⁷

He also choreographed for Oriental dancer Nagwa Fouad between 1977 and 1992; ²⁸ his collaborations with Nagwa Fouad helped elevate the status of Oriental dance in the international arts arena. In addition, he was Egypt’s representative at the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), and he was on the board of directors for one of its branches, the International Council of Organizations of Folkloric Festivals and Folk Arts (CIOFF). He directed the Ismailia International Folkloric Festival in 1985 and was asked to direct the Folkloric Festival at the Seoul Olympics in 1988. He designed and directed the opening ceremonies for the Pan-African Games of 1991, which involved 10,000 participants. From 1992 to the mid-2000s, Khalil served as the Egyptian Ministry of Culture’s Deputy Undersecretary of Egypt’s Cultural festivals. Dancer and researcher, Shareen El Safy, notes that Khalil’s “choreographies re-created the political, social and economic atmosphere of Egyptian society at the turn of the century, and in the 30s, 40s and 50s.” ²⁹

The content from this post is excerpted from The Salimpour School of Belly Dance Compendium. Volume 1: Beyond Jamila’s Articles. published by Suhaila International in 2015. This Compendium is an introduction to several topics raised in Jamila’s Article Book.

If you would like to make a citation for this article, we suggest the following format: Keyes, A. (2023). National Folkloric Dance Companies in Egypt. Salimpour School. Retrieved insert retrieval date, from https://suhaila.com/national-folkloric-dance-companies-in-egypt

1 The term “folkloric” here refers to the state-sponsored dance companies in Egypt, not to the traditional indigenous dances found throughout the country.

2 Anthony Shay, Choreographic Politics: State Folk Dance Companies, Representation and Power (Wesleyan University Press, 2002), 135.

3 Anthony Shay, “The Male Dancer in the Middle East,” 77.

4 Quoted in Shay, Choreographic Politics, 147.

5 The two films, Igaza Nisf as-Sina (1961) and Gharam fil-Karnak (1963), follow Hollywood musical formulas such as those starring Judy Garland and Mickey Rooney.

6 Quoted in Shay, “The Male Dancer in the Middle East,” 77.

7 Shay, Choreographic Politics, 149.

8 Shay, “The Male Dancer in the Middle East,” 76.

9 Shay, Choreographic Politics, 145.

10 Quoted in Shay, Choreographic Politics, 146.

11 Franken, “Farida Fahmy,” 275.

12 Quoted in Anthony Shay, “The Male Dancer in the Middle East,” 77.

13 Dance ethnologist and performer Carolee Kent (Sahra Saeeda) emphasizes this difficulty repeatedly in her four-part lecture/dance series, Journey Through Egypt.

14 Franken, “Farida Fahmy,” 275.

15 Ibid., 279. Additional sources: James Montague, “Mahmoud Reda: Egypt’s answer to Fred Astaire,” CNN, January 15, 2010, accessed December 2, 2013, http://www.cnn.com/2010/WORLD/meast/01/13/belly.dancing.reda.raqia/index.html?_s=PM:WORLD; Morocco, “Interview with Mahmoud Reda, Part 1: The Beginning,” “Part 2: The Troupe,” “Part 3: Film & Feature,” Gilded Serpent, June 19, 2003, accessed December 2, 2013, http://www.gildedserpent.com/art32/rockyredainterviewp1.htm, http:// www.gildedserpent.com/art32/rockyredainterviewp2.htm, http://www.gildedserpent.com/art32/rockyredainterviewp3.htm.

16 Farida Fahmy, “The Founding of the Reda Troupe: An Historical Overview,” last updated 2008, accessed December 2, 2013, http://www.faridafahmy.com/history.html.

17 Franken, “Farida Fahmy,” 273.

18 Ibid., 275.

19 Shay, Choreographic Politics, 138.

20 “About Farida Fahmy,” accessed December 2, 2013, http://www.faridafahmy.com/about.html.

21 Ibid.

22 Margo Abdo O’Dell, “Minneapolis: Raqia—Visionary and Emissary,” Arabesque 21:5 (1996): 13.

23 “Raqia Hassan,” The Egyptian Academy of Oriental Dance, accessed December 2, 2013, http:// egyptianacademy.com/jml2/raqia-hassan.

24 Shay, Choreographic Politics, 155.

25 Bonita Oteri, “About Faten Salama,” accessed December 2, 2013, fatensalama.wordpress.com/al- massraweya-the-real-egyptian-certification-program/about.

26 Shareen El Safy, “In Memoriam: Mohammad Khalil,” Habibi 21:2 (Fall/Winter 2006/2007): 90.

27 Shareen El Safy, “A New Concept for Woman: An Interview with Mohammed Khalil,” Habibi 12:4 (Fall 1993), http://thebestofhabibi.com/4-vol-12-no-4-fall-1993/mohammed-khalil/.

28 El Safy, “In Memoriam,” 90.

29 El Safy, “A New Concept.”