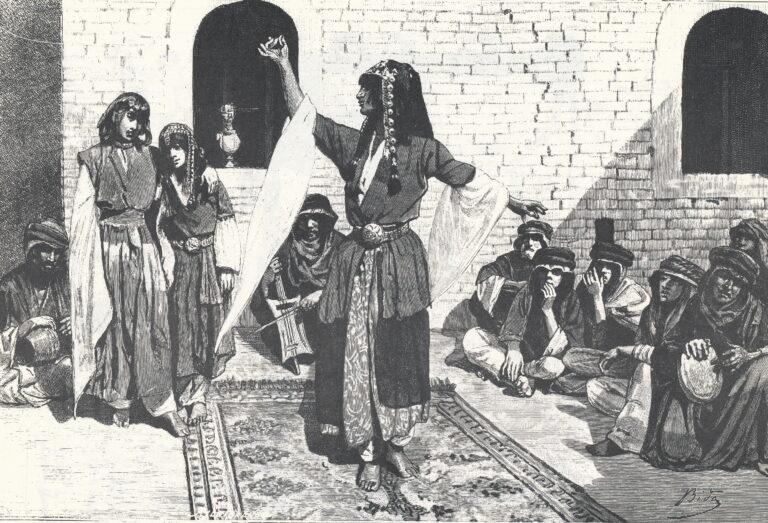

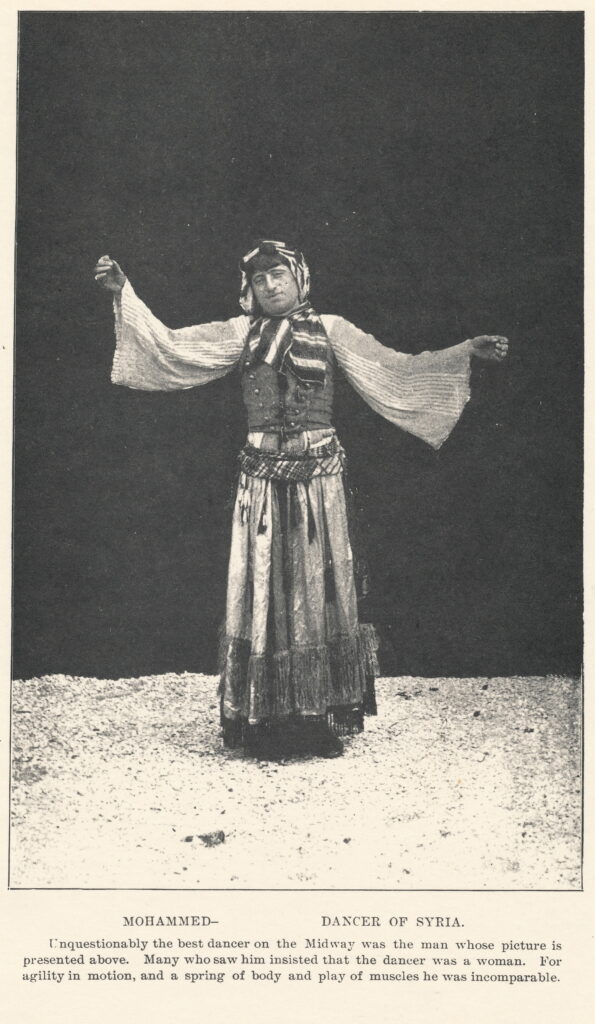

In general, Middle Eastern men pride themselves on their masculinity and strength.¹ Islamic and Christian edicts are interpreted to condemn homosexuality, so the idea of men performing a “woman’s” dance is often offensive or downright strange. That said, women are discouraged from dancing in public, for it is considered shameful, lewd, and sometimes an indicator that she is available for hire sexually. This paradox has often presented an opportunity to men to dress as women and dance in a feminine manner. Accounts from travelers in the Middle East and the Ottoman Empire tell us that the movements performed by male dancers, according to dance scholar Anthony Shay, “clearly indicate that these dance forms closely approached contemporary belly dance techniques,” and “the performances of the male and female professional dancers were almost identical.”²

Historical accounts indicate that the style of dance performed by professional dancing men and boys throughout the Middle East was much more athletic and acrobatic than both Oriental dance performed by women today and choreographies performed by national folkloric companies such as the Reda Troupe. The male dancers would perform somersaults, back flips, and handstands; all of them played some sort of hand percussion such as castanets, wood clappers, finger cymbals, or small stones held in the palms of the hands.³

Male dancers have been referenced in pre-Islamic archaeological records, such as Bagoas, a eunuch and concubine whom Darius III (the last king of the Achaemenid Empire of Persia) passed to Alexander the Great as war booty around 350 BCE.⁴

Male dancers continued to exist even under Islamic rule. The Ottoman Empire’s dancing boys, or köçek as they are called in Turkish (pronounced “kuh-check”), dressed in feminine attire, and were employed by the wealthy as entertainers. They would also dance in a style that would have been recognized at the time as women’s dance, using pelvic movements similar to modern belly dance; they were sometimes available sexually. A 17th-century European traveler described their dance as “wriggling the body (a confounded wonton posture),” and they performed in groups of six to eight dancers, and would “turn round (as the Dervishes) a long time.”⁵ J. L. S. Barholdy, a 19th-century European traveler in Turkey, estimated that there were at least 600 dancing boys in the taverns of Constantinople and that many of them were quite virtuosic performers.⁶ They were so popular that Janissaries (the sultan’s elite infantrymen) fought over them,⁷ spurring Sultan Mehmet to forbid their performances. His successor, Sultan Abdülmecid I, passed a law banishing the dancing boys in 1857 because of the distraction they caused.⁸ Many of the köçek fled to Egypt.⁹

Egypt had its own dancing boys, known as khawal, and the only accounts we have of them are from European travelers between the 18th and 19th centuries. These travelers were scandalized by not only the movements these dancers performed but, of course, the fact that they were men dressed as women. A French artist accompanying Napoleon Bonaparte’s expeditions in Egypt said that the dancing boys “presented, in the most indecent way, scenes which love has reserved for the two sexes in the silent mystery of the night.”¹⁰ Traveler Edward W. Lane wrote of dancing boys whom he observed in Cairo in the mid-19th century, saying that they impersonated women. He says their dances are “exactly of the same description as those of the ghawazi,” and that they imitated women’s dress and appearance by hennaing their hands, plucking their facial hair, and applying kohl to their eyes.¹¹ It is thought that when the Ottoman Sultan banished the köçek from Istanbul, many of them filled the void left when Muhammad ‘Ali Pasha banished the ghawazi from Cairo,¹² and many of them were employed to dance at the same celebrations as would the ghawazi: weddings, the birth of a child, or circumcisions. These boys would veil their faces, wear women’s clothing, and let their hair grow long; however, most of the public knew that they were not, in fact, women.

The term khawal in modern Arabic takes on different meanings in different dialects. In some communities it can be a neutral term for a male homosexual; in others it takes on a derogatory connotation, meaning the one who takes the passive (i.e., female) role in a homosexual act. In others it is equivalent to the English word “a**hole,” losing its homosexual implications, and turning into a general insult. Likewise, in contemporary Turkey, köçek means both “transsexual” and “transvestite.” ¹⁴

The presence of male dancers in the Middle East waned after World War I, most likely because of the introduction of prudish and homophobic Victorian mores by European colonial authorities. Dance scholar and choreographer Anthony Shay argues that in the 1950s, when Egypt (and other nations in Middle East and Central Asia) were developing national folkloric dance companies, that choreographers deliberately changed the style of dance performed by men. He claims that choreographers like Mahmoud Reda, “consciously attempted to erase the equation of dancer, male or female, with prostitution, by erasing or altering any movements he perceived as overtly sexual.” The movements became more “masculine” than what we might have seen performed by the köçek of the Ottoman Empire. ¹⁵

Although the movements had changed dramatically, the tradition of the male public dancer was still alive in the 1960s, in the firqat zaffa (group of musicians and dancers hired to lead a wedding procession) of Cairo. Dressed in Western clothing, a group of twelve to twenty young male dancers, playing Egyptian drums (and sometimes Western instruments such as the saxophone or trombone), would appear first in the procession, followed by young girls carrying candles, and a female solo dancer. The male dancers would perform at about a tenth of the solo female performer’s fee, and conservative pressure on public zaffa has contributed to the disappearance of the female solo performer leading the procession. If the zaffa took place in a hotel only, however, the female dancer would still perform, unless the wedding party wanted to save money on entertainment.¹⁶ Karin Van Nieuwkerk says that as of the mid-1990s there were no male belly dancers performing in Egypt, only folk dancers (à la Mahmoud Reda) and performers in wedding processions as described above. They are not valued, she says, not necessarily because dancing itself is immoral, but rather because they do “women’s work.” Men’s bodies, according to Van Nieuwkerk’s interviews with Egyptian people and religious leaders, are neither considered “shameful” nor “exciting.” ¹⁷

The content from this post is excerpted from The Salimpour School of Belly Dance Compendium. Volume 1: Beyond Jamila’s Articles. published by Suhaila International in 2015. This Compendium is an introduction to several topics raised in Jamila’s Article Book.

If you would like to make a citation for this article, we suggest the following format: Keyes, A. (2023). Male Dancers in the Middle East. Salimpour School. Retrieved insert retrieval date, from https://suhaila.com/male-dancers-in-the-middle-east

1 For the scope of this study guide, we make a broad generalization. Of course, not every man of Middle Eastern descent holds the views presented here.

2 Anthony Shay, “The Male Dancer in the Middle East and Central Asia,” in Belly Dance: Orientalism, Transnationalism, and Harem Fantasy, ed. Anthony Shay and Barbara Sellers-Young (Costa Mesa, California: Mazda Publishers, 2005), 66.

3 Ibid., 65.

4 Ibid., 55.

5 James T. Bent, ed. “Dr. John Covel’s Diary (1670-1679),” in Early Voyages and Travels in the Levant, (London: Hakluyt Society, 1893), 213-214, accessed December 29, 2014, https://openlibrary.org/books/OL13500243M/Early_voyages_and_travels_in_the_Levant.

6 J. L. S. Barholdy, Voyages en Gréce fait dans le années 1803 et 1804, Traduit de l’Allemand par A. du C. Paris 1807, II, 88, accessed December 29, 2014, https://openlibrary.org/books/OL6949065M/Voyage_en_Gre%CC%80ce_fait_dans_les_anne%CC%81es_1803_et_1804.

7 Stavros Stavrou Karayanni, Dancing Fear and Desire: Race, Sexuality, & Imperial Politics in Middle Eastern Dance (Ontario: Wilfred Laurier University Press, 2004), 78.

8 Penni AlZayer, Middle Eastern Dance, (Philadelphia: Chelsea House, 2003), 93.

9 Metin And, A Pictorial History of Turkish Dancing: From Folk Dancing to Whirling Dervishes—Belly Dancing to Ballet (Ankara: Dost Yayinlari, 1976), 141.

10 Shay, “The Male Dancer in the Middle East,” 54.

11 Lane, Manners and Customs, 100.

12 Penni AlZayer, Middle Eastern Dance, 94.

13 Karayanni, Dancing Fear and Desire, 79; Lane, Manners and Customs, 389.

14 Karayanni, Dancing Fear and Desire, 28.

15 Shay, “The Male Dancer in the Middle East,” in Belly Dance, 76.

16 Kent and Franken, “A Procession Through Time” 74.

17 Van Nieuwkerk, ‘A Trade Like Any Other’, 132.