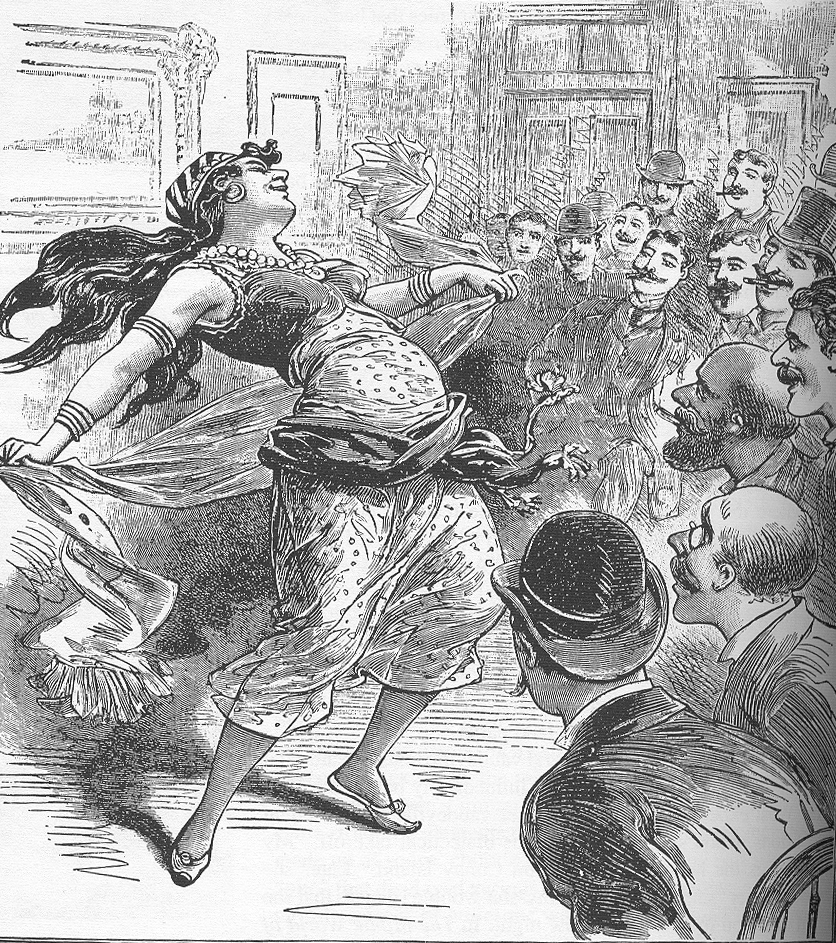

“Little Egypt” was not so much a dancer, but the idea of a dancer, a name used to describe any number of Oriental-influenced performers on American vaudeville, burlesque, and carnival stages. It is difficult to trace where and when “Little Egypt” first appeared on the American stage, as evidenced in Jamila’s own writings, with some scholars pointing to the “A Street in Cairo” attraction on the Midway at the World’s Columbian Exposition (commonly called the Chicago World’s Fair) in 1893, earlier at the Philadelphia Centennial in 1876, or even later at the St. Louis Fair of 1904.¹ The impresario responsible for the Oriental exhibitions at the Chicago World’s Fair, Sol Bloom, famously denied there ever being a dancer named Little Egypt; he claims the name belonged to one of the riding camels at the Street in Cairo concession.² Regardless of when belly dance—or danse du ventre, as it was often called, French for “dance of the stomach” sounded more exotic or refined, depending on the audience—first debuted in the United States, its appearance at the Egyptian “A Street in Cairo” exhibit at the Chicago World’s Fair garnered the most publicity. The Board of Lady Managers protested the performances, calling for them to be shut down for indeceny. Her condemnation backfired, as newspapers picked up the story and attracted even more visitors to the fair.³

The dancers who performed under the stage name “Little Egypt” were often known as “cooch” dancers, or billed as doing the “hootchy-cootchy.” The origin of the term “hootchy-cootchy” is spotty, with some saying it comes from Cooch Behar, a region of India. Writer Donna Carlton claims that the term comes from the French combination of hochequeue, literally meaning, “to shake the tail.” A bird of the same name, also known as a wagtail, continually fluffs and shakes its tail feathers while standing. The term, Carlton claims, likely came to the United States through the French territory of Louisiana, which was a hub of the slave trade. She says that attribution of the little bird’s shaking to a dance performed by people, more specifically African slaves, began in New Orleans, where whites “observed black social dances” in the early 1900s. The term then became a more generic term for any sort of dance involving shaking of the hips, including “African-American ritual and social dance and the Oriental or pseudo-Oriental theatrical dance.” She also reminds her readers that the term “hootchy-cootchy” never appeared in promotional materials for the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, nor did the name “Little Egypt.”⁴

We do know that the name “Little Egypt” can be attributed to at least three specific performers of the late 19th and early 20th century: Ashea Wabe, Farida Mazar Spyropolous, and Fatima Djemille. Donna Carlton adds Saida DeKreko, Catherine Devine, and Gertrude Warnick as other performers who claimed to be “the original.”⁵ Two dancers who appeared on early film recordings, Fatima and Raja, are also sometimes referred to as “Little Egypt,” and were quite possibly from the Middle East.⁶ In addition to these three performers, the name “Little Egypt” became a term for any solo female performer of the hootchy-cootchy, no matter how inauthentic or corrupted the actual dance was from its Middle Eastern roots. The name and idea also spawned many “imitations dressed in beaded tops and transparent skirts who very often did not even attempt to try to dance baladi.”⁷

As for the dancers themselves, according to Donna Carlton, Farida Mazar Spyropolous did indeed dance on the Midway Plaisance at the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893, but not as “Little Egypt.”⁸ Details of her life and career are spotty, although it’s likely that she was born in Damascus, in what is now Syria, then lived in Cairo. She came to the United States when she was sixteen, where she probably lived in Chicago. At the time of the Chicago World’s Fair, she was 21; after the fair, she toured as a solo act, appearing in San Francisco, New York, and Havana, Cuba.⁹ She stopped dancing regularly after she married a restaurateur, although she did appear at the 1915 Panama-Pacific Exposition in San Francisco, and the 1933-34 Century of World Progress World’s Fair in Chicago.¹⁰ She felt the 1936 film The Great Ziegfield tarnished representation of “Little Egypt,” and also did not like to be called “Little Egypt,” saying, “Egypt is a country… not a girl.”¹¹

A petite Algerian dancer named Ashea Wabe greatly popularized the name “Little Egypt” when she became the focus of a New York City scandal in 1897, known as the Seeley Dinner. When she was hired for a “dance and a pose” at the bachelor party of one of P. T. Barnum’s grandsons, police raided the party. The guests and Wabe were called before the Board of Police Commissioners and a grand jury for questioning, as it was “widely reported” that Wabe had taken off “her garments one at a time” at the party.¹2 She claimed that what she did was “proper for ar-r-r-t,” and no charges were filed.¹³ The trial led to fame, and Oscar Hammerstein I, who owned the famous Olympia vaudeville theater on Broadway in New York, hired Wabe at the then large fee of a thousand dollars a week to perform in a skit based on the scandal. After Wabe’s appearance on Broadway, a host of imitators calling themselves “Little Egypt” began appearing at Coney Island, vaudeville, circus acts, and carnival shows.¹⁴ In fact, so many carnivals and traveling sideshows featured cooch shows, elephants, and camels, and other “Oriental-flavored amusements” that their operators were often known as “sheikhs.”¹⁵

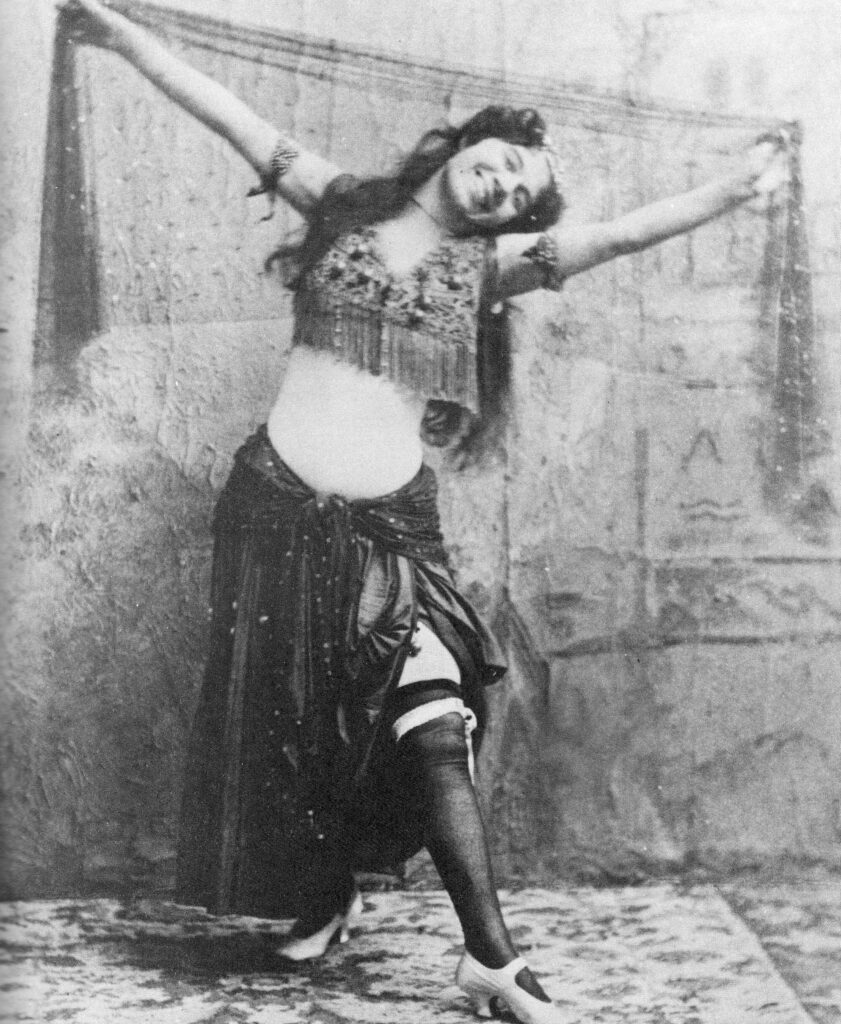

The World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893, with its towering Ferris Wheel, grand artificial lakes, and neo-classical buildings, inspired the first amusement parks, and the hootchy-cootchy found its way to seaside boardwalks, such as Coney Island, and American carnivals. Some photographs from 1896 provide an image of a sideshow dancer who has the appearance of being genuine: Fatima, a Coney Island performer. Her costume has “authentic touches” and it is she who appears in an early film called “Fatima’s Dance” from 1897. Fatima performed her “Coochie-Coochie” dance for early filmmakers, including the famous clip recorded by Thomas Edison in which she performs a series of shoulder shimmies. The original footage had been censored, with long horizontal white blocks covering her torso and hips, because, as scholar Rebecca Stone says, “the shimmy was considered to be the most wicked and even the most unhealthful dance of the day.”¹⁶ Indeed, police arrested cooch dancers at Coney Island, and some cities threatened to shutdown traveling sideshows for featuring these immodest performances.¹⁷

Despite being perceived as lewd (or perhaps because of it), as the United States entered the 20th century, Americans could not get enough of the strange and exciting hootchy-cootchy, and it became a quintessential feature of vaudeville and burlesque shows.¹⁸ Not only did Little Egypt appear uncorseted, but she also performed in public movements that highlighted her chest and hips—acts that a proper woman just would not do. In Chicago, Sam T. Jacks—a theater owner and producer—claimed that he had introduced “Little Egypt” to the burlesque world at his own venue; regardless of who actually did first put an imitation Oriental dancing girl on the stage, the cooch dancer had become a standard, perhaps even requisite, character on the burlesque stage.¹⁹ She was first featured as an “added attraction,” and Mae West infamously experimented with the character in her vaudeville days, with furious stage managers threatening to dismiss her.²⁰ These dancers played up the scandalous aspects of the original, if they knew anything of what the original dancers performed at all; they would, however, often name themselves something “Oriental,” such as Fatima, Cocheeta, or even just Little Egypt.²¹

In all her notoriety, Little Egypt as a character is often credited with being the first “striptease” act. Historian Charles A. Kennedy tells us that at the St. Louis Fair of 1896 a “World’s Fair celebrity” by the name of Omeena performed a “take-off,” which he interpreted to be, perhaps, the first striptease act in the United States.²² The Seeley Dinner incident in 1897 involving Ashea Wabe also contributed to the connection between Little Egypt and striptease; whether or not she actually had removed her clothing one piece at a time was not as important to the public as the idea that she had. Donna Carlton notes that four years before the St. Louis Fair, an artist’s model known as Mona had taken off her clothing at the Four Arts Ball held at the Moulin Rouge in Paris. Her arrest sparked riots amongst Parisian students, and the controversy, says Carlton, inspired striptease performances in Paris, which first appeared on the stage in 1894.²³ We might even trace the first influential striptease back to Gustave Flaubert’s encounter with Kutchek Hanem, a ghawazi courtesan, who performed what Flaubert described as the “Bee” in which Hanem “shed her clothing as she danced.”²⁴

Burlesque

Burlesque had not always been about stripping, as we often think today, or as contemporary burlesque revival shows often are. The word itself comes from the Italian burlesco, which, itself comes from the Italian burla, meaning a joke, ridicule or mockery. The original burlesque shows of the Victorian era were parodies and caricatures, lampooning current affairs and politics, often by using classical or historical characters. Women dominated the genre in its early days, writing, producing, and performing the shows. According to Alan Trachtenberg they challenged “notions of the approved ways women might display their bodies and speak in public” by “reversing roles” and “shattering polite expectations.”²⁵ Lucinda Jarrett says that it differed from more legitimate theater in that it parodied sexual matters through a “confident female sexuality,” offering a sense of promiscuity through economic independence.²⁶ Scholars of burlesque’s American history trace the introduction of the form back to Englishwoman Lydia Thompson, whose troupe came to the United States in 1896, and with great success.²⁷

Her appearance inspired dozens of imitators, but after the turn of the century, when the genre became more professional, men began to take over as managers and promoters. With men in charge of the female performers, and the appearance of the hootchy-cootchy at fairs and boardwalks, burlesque shows increasingly featured the “voiceless female body in stylized erotic gyrating motion, starting with the cooch dance in the 1890s and the shimmy and striptease dances of the early 20th century.”²⁸ As burlesque degenerated from striptease to the all-out stripping and “live nude girls” of the mid-20th century and later, these industries continued to cite the hootchy-cootchy as their source. Andrea Deagon notes that strip tease promoter Paul Alt specifically linked belly dance to the origins of strip tease.²⁹ Whatever our opinions of burlesque and striptease today, it is clear that they have their roots in the same historical performances as our own Oriental dance.

The content from this post is excerpted from The Salimpour School of Belly Dance Compendium. Volume 1: Beyond Jamila’s Articles. published by Suhaila International in 2015. This Compendium is an introduction to several topics raised in Jamila’s Article Book.

If you would like to make a citation for this article, we suggest the following format: Keyes, A. (2023). Little Egypt, Hootchy-Cootchy and Burlesque. Salimpour School. Retrieved insert retrieval date, from https://suhaila.com/little-egypt-hootchy-cootchy-and-burlesque

1 Charles A. Kennedy, “When Cairo Met Main Street: Little Egypt, Salome Dancers, and the World’s Fairs of 1893 and 1904,” in Music and Culture in America: 1861-1918, ed. Michael Saffle (New York: Garland Publishing, 1998), 271.

2 Donna Carlton, Looking for Little Egypt, (Bloomington, Indiana: IDD) 73.

3 Bentley, Sisters of Salome, 36.

4 Carlton, Looking for Little Egypt, 57-9.

5 Ibid., 65.

6 Rebecca Stone, “Reverse Imagery,” 251.

7 Janet Johnstone and G. J. Tassie, “Egyptian Dance – A Contested Tradition,” in Managing Egypt’s Cultural Heritage, ed. F. A. Hassan & G. J. Tassie, A. de Trafford, L. Owens and J. van Wetering, proceedings of the first Egyptian Cultural Heritage Organisation Conference on: Egyptian Cultural Heritage Management (London: Golden House Publications, 2009), 110-111.

8 Carlton, Looking for Little Egypt, 45.

9 Ibid., 71.

10 Ibid., 45.

11 Ibid., 73.

12 Bentley, Sisters of Salome, 36.

13 Saint Louis Dispatch, quoted in Carlton, Looking for Little Egypt, 79.

14 Bentley, Sisters of Salome, 36.

15 Carlton, Looking for Little Egypt, 59.

16 Stone, “Reverse Imagery,” 251.

17 Carlton, Looking for Little Egypt, 61.

18 Ibid., 59.

19 Robert Clyde Allen. Horrible Prettiness: Burlesque and American Culture, (Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press, 1991), 250.

20 Carlton, Looking for Little Egypt, 59, 61.

21 Ibid., 61.

22 Kennedy, “When Cairo Met Main Street,” 280.

23 Carlton, Looking for Little Egypt, 79.

24 Gustave Flaubert, Flaubert in Egypt: A Sensibility on Tour, trans. and ed. Francis Steegmuller (Chicago: Academy Chicago Ltd., 1979), 117.

25 Alan Trachtenberg, forward in Horrible Prettiness: Burlesque and American Culture by Robert Clyde Allen (Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press, 1991), xii.

26 Lucinda Jarrett, Stripping in Time: A History of Erotic Dancing (London: Pandora, 1997), 137.

27 Allen, Horrible Prettiness, 159-60.

28 Trachtenberg, forward, xii.

29 Andrea Deagon, “Dance of the Seven Veils: The Revision of Revelation in the Oriental Dance Community,” in Belly Dance: Orientalism, Transnationalism, and Harem Fantasy, ed. Anthony Shay and Barbara Sellers-Young (Costa Mesa, California: Mazda Publishers, 2005), 266.