Percussion Instruments

Tabla/Darbuka

(Commonly called doumbek in the United States). The quintessential percussion instrument for Middle Eastern dance music, ubiquitous from North Africa to Turkey, the “tabla” is a goblet-shaped drum that can be found in a variety of sizes. It should not be confused with the Indian tabla; the two have little relation.

Commonly called the darbuka in the Middle East and Europe, it is used for both folk music and art music, as well as contemporary pop music. It is traditionally made from clay with a head of goat or sheepskin; experienced and professional players often prefer heads made of fish skin. A lighter metal form of the drum is common in Turkey.

In recent decades, the instrument has been made with an aluminum body and a plastic tunable head, allowing the drummer to adjust the instrument\’s pitch and tuning to a particular song. This also gives confidence that the pitch will not change; humidity, temperature, and weather changes can affect the tension and tone of animal skin heads.

The darbuka is held in the lap, resting on the player’s thigh (most often on the left), and played with the hands, the fingers providing the various hits, heavy and light, often with remarkable speed and skill.

Riqq

The riqq is a tambourine, with double pairs of cymbals, usually arranged in groups of five around the frame. It is played upright, held in one hand (typically the left), and both hands are used in producing the sound, which is a combination of hitting the skin and the cymbals (called zills, silsil, sagat, or sajat) with the fingers.

As with the darbuka, it is traditionally wooden (often decorated with beautiful mother-of-pearl inlays in geometric patterns), with an animal skin for a drum head; but in the last several decades, metal and plastic versions have become increasingly common, allowing for fine-tuning and greater control.

Like the darbuka, it is popular throughout North Africa and the Middle East, and players can show astonishing levels of virtuosity. It pairs well with the darbuka and with frame drums.

Tar

The tar is a simple frame drum, essentially a skin stretched over a round, wooden frame, hence it is also commonly known as a frame drum. It may be played held up in both hands (allowing the drummer to stand) or resting on the knee, if the player is sitting.

Such drums are very ancient, and versions of them are depicted in carvings and art from Mesopotamia and Egypt, dating back more than 3,000 years. Drums of this kind exist in primal cultures throughout the world.

The word “tar” also rather confusingly refers to a Moroccan type of tambourine used in traditional North African music (in the Andalusian nūba repertoire) and to stringed instruments from Iran and India (i.e., “sitar’).

Finger Cymbals

(Sagat, Zagat, Sajat, Zills, Silsil). These are small cymbals in sets of four, one attached to the thumb and middle finger of each hand, played in alternation to make rhythmic patterns.

They are available in several sizes, the larger ones generally being louder. While they are known for being the instrument played by professional dancers in the Middle East, they are also used in a purely musical context, especially in classical Persian music.

Duff/Deff

The duff is similar to the tar, and the words can be used interchangeably, though sometimes the duff is smaller in size and played more with slaps than with the virtuosic finger techniques used for the tar, and used as a supporting rhythmic instrument in a larger ensemble.

These should not be confused with the daf, a Persian frame drum with lengths of chain hanging from the inside of the rim, so that when the drum is struck, it produces a loud, rattling sound.

Mazhar

The mazhar is a kind of “larger cousin” to the riqq, with louder cymbals. It is not played with the same level of technique as the riqq, and is often used in outside performances with other loud instruments, as well as in rituals and celebratory music.

Dohalla

This is a larger, bass version of the darbuka, popular in folk music and certain rituals, such as the zār. Like the darbuka, it is made both in traditional and modern versions.

Tabla Baladi/Davul

Traditionally, this is a large wooden, double-sided drum, held in front of the body with a strap and played with two sticks, one thick (most often held in the right hand), and one thin (held in the left, called a switch). It produces a loud sound appropriate for accompanying other loud instruments, such as mizmars or bagpipes, in outdoor settings.

A very popular instrument in Upper Egypt (the south), nearly identical versions exist in Turkey (the davul), and the Balkans (the tapan), where they are also used for folk music.

Bendir

The bendir closely resembles the tar, with the addition of strings stretched across the inside that act as snares, vibrating when the head of the drum is hit. It is most often played standing up.

The instrument is an essential component of Moroccan folk music (where a dozen or more bendir drummers may play a simple pattern simultaneously, accompanying other instruments), but is also found in other countries, and is popular in, for example, sufi rituals.

Qarqabat

(singular qarqaba, also krakebs or garagab). These loud metal instruments are like a combination of finger cymbals and castanets and are a principal feature of the Gnawa music of Morocco (the Gnawa incorporate elements of Sufism and pre-Islamic belief into their rituals).

Like finger cymbals, they are in sets of four, two held in each hand, but each set is tied together with string, leather, or elastic to facilitate easier playing. The sound is flat, rather than ringing like finger cymbals, and is quite loud. They are played in conjunction with hand clapping, singing, and melodic instruments.

Pandeiro/Square Drum

Known as “story-teller’s drums” in North Africa, these are square-shaped drums with a skin stretched over both sides and sometimes a bell hanging from a string on the inside, to produce a jingling sound when the instrument is struck.

They were very popular in Jewish communities in medieval Spain and are often decorated with henna patterns then and now. The pandeiro should not be confused with a South American drum of the same name.

Melodic Instruments

Plucked Strings

‘Ud

(oud in French, a commonly used spelling). The primary instrument of Middle Eastern art music, the ‘ud has a very long history. Pear-shaped lutes seem to have originated in Central Asia and were known in ancient Egypt and the Greco-Roman world.

The Arabic al-‘ud translates as “wood,” giving an indication of its construction and indeed, its importance. The English word “lute” derives from this Arabic term.

The Moors brought the instrument into Europe when they occupied Spain in the 8th or 9th centuries; crusaders also brought it west from the Levant beginning in 12th century. In Europe, it changed over time and became an essential part of European classical music from the 15th to the 18th centuries.

The ‘ud today still resembles its medieval ancestor and holds a prime place of importance in Middle Eastern music instruction and performance. Indeed, the maqām system is best illustrated by using the instrument.

It is fretless, like a violin, allowing for the playing of the many microtonal scales in Arabic and Turkish music. It is held similarly to a guitar, and the player plucks the strings with a plectrum. Traditionally this was a feather quill, a rishah, or perhaps a piece of shaped horn; today it is common for the pick to be made of plastic or hard rubber.

The ‘ud generally has five pairs or “courses” of strings, and often an additional single string, for a total of eleven. It is played with other instruments in groups, and also has a highly regarded status as a solo instrument, where it can be used to show off the maqāmāt to great effect by skilled players.

Solo improvisations, known as taqāsīm (sing. taqsīm), are one of the most attractive types of pieces, and the ‘ud is perhaps uniquely suited for them. It is also considered an excellent instrument to accompany a solo singer.

The ‘ud can be heard in almost every genre of Middle Eastern music, from folk to classical and art music, to pop, to Sufi and ceremonial music. It is prized from Morocco to Turkey, and while more modern instruments, such as the guitar, have replaced it in some cases, it will likely always be held up as the perfect Middle Eastern instrument

Qanun

The qanun is a box-like zither, in a half-trapezoidal shape, across which is strung between 63 and 84 strings, tuned to a particular maqām, in sets of three. Traditionally these were made of gut, but in modern times, they are most often nylon.

It is laid in the lap of the seated musician and played with finger picks worn on both hands, giving a sound that is both sharp and soft at the same time. The two different hands usually play the same notes at eight notes (an octave) apart, giving the instrument a unique expansive quality.

Each set of strings also has a series of levers or bridges (‘urab), which can be raised or lowered across each set of three strings to alter the pitch of that set in very subtle ways, allowing for the musicians to rapidly retune and adjust to a new maqām. Literally, qanun means “law” in Arabic, suggesting that the qanun player sets the tuning for the other musicians in that particular ensemble.

Like the ‘ud, the instrument found its way into medieval Europe, where it became known as the psaltery (from the Greek psalterion, meaning “sing,” “psalter” and “psalm” share the same root), which was often strung with wire strings.

In the later 14th century, keys were attached to pluck the strings, leading to the creation of the harpsichord in the 15th century, which would become a dominant instrument in Western classical music for the next three centuries.

Ultimately, the piano derived from the harpsichord, and thus the qanun can be said to be its distant ancestor. Like the ‘ud, it is used both in ensembles and as a solo instrument, and is well suited to performing the taqsīm form.

Simsimiyya: The simsimiyya is a lyre (a kind of harp) with a small number of strings (usually six to eight), used in ensembles, both among the Egyptian Bedouin and in cities such as Port Said in Egypt (where it accompanies a dance called the bambutiyya), as well as in Jordan and Yemen.

It may have some link to ancient lyres of the kind still played in Ethiopia (the krar), or perhaps even those from ancient Greece (such as the kithara and chelys) or Egypt and the other civilizations of the ancient Near East, but it is difficult to prove a direct link.

Saz

The saz is one of the principal instruments of Turkish folk music and is a direct descendant of long-necked, pear-shaped lutes from Central Asia, brought by Turkic peoples as they migrated westward into Asia Minor (modern Turkey).

The word “saz” can refer to this family of instruments, while the Turkish instrument is commonly known by the various sizes of the instrument (from very small to quite large), of which the bağlama (pronounced “BAH-lah-mah”) is the most popular, though these terms are also used interchangeably.

The saz is strung with three sets of wire strings: three groups of two, or sometimes two groups of two and one group of three. This produces a sound that is thinner and sharper than that of the ‘ud, though it is also played with a plectrum.

The front of the instrument, the wooden soundboard, can be tapped with the fingers or knuckles to create percussive effects. Unlike the ‘ud, the saz has frets, like a modern guitar, arranged in such a way as to allow for certain microtonal scales to be played. They are tied to the neck, and so can be adjusted as needed.

The saz and its repertoire have a distinctly “Turkish” and Central Asian sound, while still making use of the same maqāmāt and rhythms as are found in Arabic music. This synthesis of the two gives Turkish music its unique quality.

The saz is related to the Greek bouzouki and the Syrian buzuq, as well as the Balkan tamboura, all of which are wire-strung lutes adapted to the traditional music of each region.

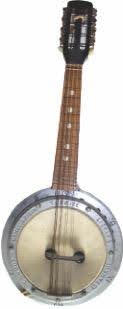

Cümbüş

(pronounced “joomboosh”). This odd Turkish instrument dates only from the early 1930s and resembles the American banjo, while frequently having a fretless neck and being tuned similarly to the ‘ud.

The body is made of lightweight metal, resembling a cooking pot, with a plastic skin as a soundboard that vibrates when the strings are plucked, giving the instrument an echo-like sound when played.

The instrument was invented by Zeynel Abidin, and it so impressed Turkish leader (and founder of the Turkish Republic) Mustafa Kemal Atatürk that he asked that it be named cümbüş (Turkish for “fun,” “entertainment,” or “to be funny”). He felt that it would be ideal as an inexpensive instrument that could be enjoyed anywhere.

Abidin was so flattered that he adopted “Cümbüş” as a family name, and the fourth generation of the Cümbüş family still makes the instrument in Istanbul. The instrument became so popular that it eclipsed the ‘ud in some areas of Turkey.

Sehtar

A small long-necked and fretted lute from Iran, similar to the saz, the sehtar is also a descendant of earlier Central Asian lutes. While the name is similar to the Indian sitar, the two are only distantly related and do not resemble one another at all.

It is played delicately with the fingernails (or finger picks) rather than a plectrum. The sehtar is used both in Persian classical music and in Sufi music.

Bouzouki (Greek)/Buzuq (Syrian)

Both of these instruments derive from the saz family, having been adapted to the requirements of folk music in each region. They are long-necked lutes with frets, played with plectra, and the Syrian version has its frets placed to play certain microtones.

In Bulgaria, a similar instrument is called the tambura. Traditional Irish music makes use of a mandolin-like lute sometimes called the “Irish bouzouki,” but this is more properly known as a cittern.

However, it probably ultimately does come from the same instrument family.

Bowed Strings

Rababa

This term describes a number of bowed instruments played in various regions of the Middle East and North Africa.

Most commonly, it is a small fiddle played upright (resting on the lap or occasionally the ground), with a body made from half a coconut shell, a skin stretched over the face, and a cylindrical neck. The instrument has two strings and is played with a bow.

In Iraq, it is commonly called a joza.

The rabab or rebab in North Africa normally refers to a smaller, teardrop-shaped instrument that is also held upright and bowed. This version is an instrument of Andalusian art music and has an ancient history. Versions are depicted in medieval Spanish manuscripts that are virtually identical to the ones used today.

In Lebanon and the Levant, the term can refer to a folk fiddle with one string. It has a rectangular shape, skin for a sound board, and is also played upright. In those regions, it is popular among the Bedouin.

Kamanjah/ Kamancheh/Kemençe

As with other terms, this word actually refers to several different instruments that have some similarities.

Prior to the 20th century, kamanjah usually referred to the coconut shell fiddle; however, people use the term to denote the European violin, which has supplanted many of the traditional bowed instruments because of its greater volume, expressiveness, and range. Certainly, not everyone is happy with this development.

The kamancheh is an important instrument in Persian classical music, similar to the rababa, but with wire strings. (Traditionally, they were made of silk, as were the strings of many Central Asian lutes).

The Turkish kemençe refers to two different instruments.

- One instrument is a small, teardrop-shaped instrument held upright in the lap that is a central feature of Ottoman classical music. A very similar instrument, called a lyra, is used in the folk music Greece, the Greek islands, and Crete.

- The other instrument is the karadeniz kemençe, an elongated fiddle from the Black Sea area of North Turkey with wire strings and played standing up. Its shape resembles some European medieval fiddles and may perhaps have origins from Byzantine times.

Wind Instruments

Mizmar/Zurna

Both of these words refer to a loud, double-reed instrument played outdoors (at weddings, parties, and other large gatherings), commonly with the tabla baladi. In Egypt, mizmar is also the name for the group that plays it, usually consisting of three mizmar players and one tabla baladi drummer.

In Turkey, the zurna is essentially the same instrument, used with the davul.

Variations on the instrument are widespread throughout the region. It is likely the ancestor of a European woodwind known as the shawm, popular in the Middle Ages and Renaissance. The shawm is related to the oboe, which appeared in the 17th century.

Nay/Ney

An ancient bamboo flute popular throughout the Middle East, the nay (pronounced “nigh”; the ney is pronounced “nay” in Turkish) is perhaps one of the oldest instruments in continual use. Versions of it may date back more than 4,000 years.

It is constructed simply: a hollow tube of bamboo, with finger holes and open ends on both sides. The sound is made by blowing through the tube, something which takes considerable practice to produce a good tone. Different lengths and thicknesses of bamboo will determine the pitch. The shorter and thinner the cane, the higher the tones will be.

The nay is one of the principal instruments of Middle Eastern art music, as well as folk repertoires. It is highly praised in Arabic, Turkish, and Persian music.

The Turkish version has a mouthpiece set over the end, and the Persian flute is played by placing the edge of the cane against the teeth, which produces a hissing sound and is extremely difficult to master. It is very popular in both Turkey, where it is frequently used in Mevlevi (“whirling dervish”) Sufi ceremonies, and Iran, where it features in traditional Persian classical music.

Mijwiz

The mijwiz is a common folk instrument in Egypt and the Levant. The word means “married,” or “dual,” and as such, it consists of two short bamboo pipes tied together, with an equal number of finger holes carved into each.

When blown, the sound is buzzy, similar to a kazoo, but the two pipes, which are almost never perfectly tuned to each other, produce a chorused sound. It is commonly used for dance music, such as the debke.

Arghul

The arghul is similar to the mijwiz, except that one of the bamboo pipes has no finger holes and is considerably longer than the melody pipe. As such, the long pipe produces a continuous note, known as a drone, and the instrument resembles the bagpipe in sound.

Like the mijwiz, it is commonly used in the Levant and Egypt to accompany folk dances. Both the arghul and the mijwiz may be very old, deriving either from ancient Egyptian winds, or perhaps from the ancient Greek double-pipe instrument called the aulos.

Western Instruments

Violin

The violin, as we saw above, is commonly known as the kamanjah in the Arab world and has come to replace the more traditional bowed instruments in many professional settings (less so in folk music), ironic given that it derives from various medieval bowed instruments that were themselves influenced by Middle Eastern originals.

Western violins, being fretless, lend themselves quite well to the playing of maqāmāt and are often a principle instrument featured in contemporary ensembles, especially in music made for raqs sharqi.

Keyboard

Modern electric keyboards offer versatility to bands in being able to provide numerous sounds. Beginning in the 1960s, various keyboards have entered the Middle Eastern music repertoire, including electric organs, synthesizers (such as those invented by Dr. Robert Moog), and others.

The keyboard has often taken the place of the qanun or accordion, but it can also simulate strings and whole orchestras, as well as adding drum sounds. Its portability makes it an ideal compromise, an entire ensemble in one package.

Electric Guitar

From the 1970s, the electric guitar has become more prominent in Arabic music, taking the place of the ‘ud, though never really supplanting it. With its decidedly “Western” sound bringing the quality of rock or pop songs, it can still work well in playing more traditional-sounding music, though it is hindered by its fret placement, making some microtones difficult, if not impossible, to produce.

Omar Khorshid, who played electric guitar with Umm Kulthum, is often recognized for his innovative playing of the instrument to include quarter tones.

Accordion

Popular in Arabic night clubs from the 1930s, the accordion has been adapted to the needs of the maqām system and is now found throughout the Middle East, though the electric keyboard has sent it into something of a decline in the last few decades, with its synthesized accordion sound options. The accordion is also an essential instrument in many repertoires of Balkan folk music.

Drum Kit

The drum kits used in Western rock and jazz music have also found a place in modern Middle Eastern songs, most commonly as a supporting rhythm section, taking the role of the traditional duff and similar drums. Rarely, if ever, will the kit replace traditional percussion entirely. Rather, its role is complementary, allowing master darbuka players, for example, to show off their skills while the kit holds down the rhythm.

The content from this post is excerpted from Middle Eastern Music: History & Study Guide. A Salimpour School Learning Tool published by Suhaila International in 2018. This Music Book is an introduction to the music theory and main music exponents in the history of belly dance.

If you would like to make a citation for this article, we suggest the following format: Keyes, A. and Rayborn, T. (2018). Instruments. Salimpour School. Retrieved insert retrieval date, from https://suhaila.com/instruments