French emperor Napoleon Bonaparte’s Egyptian Campaign (1798-1801) spurred a lasting interest in all things Egyptian surged throughout Europe and the United States, a phenomenon known as Egyptomania. Through several resurgences, Egyptomania has left an enduring legacy in art, architecture, advertising, and fashion, known as Egyptian Revival.¹ For the purposes of this study guide, there were two notable periods of Egyptian Revival: that beginning in the mid-19th century after Napoleon’s Egyptian Campaign, and the other being spurred by the discovery of King Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922. Egyptologist Bob Brier notes that other waves of Egyptomania ignited when massive ancient Egyptian obelisks were brought from Egypt to Paris, London, and New York City in the 19th century.²

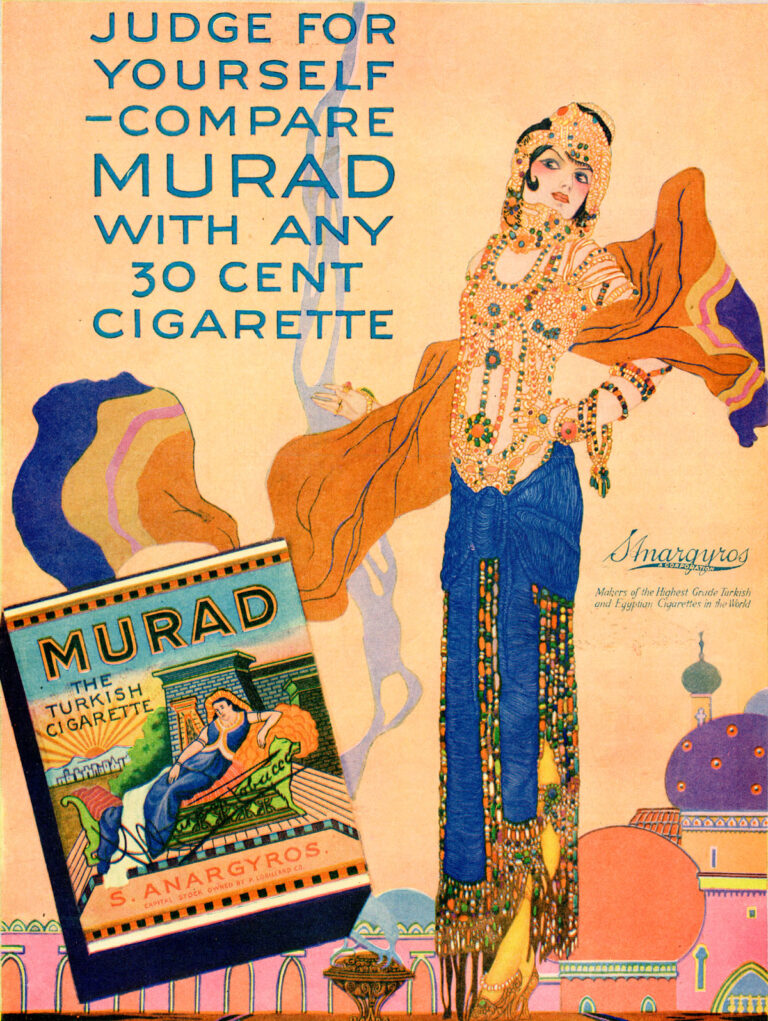

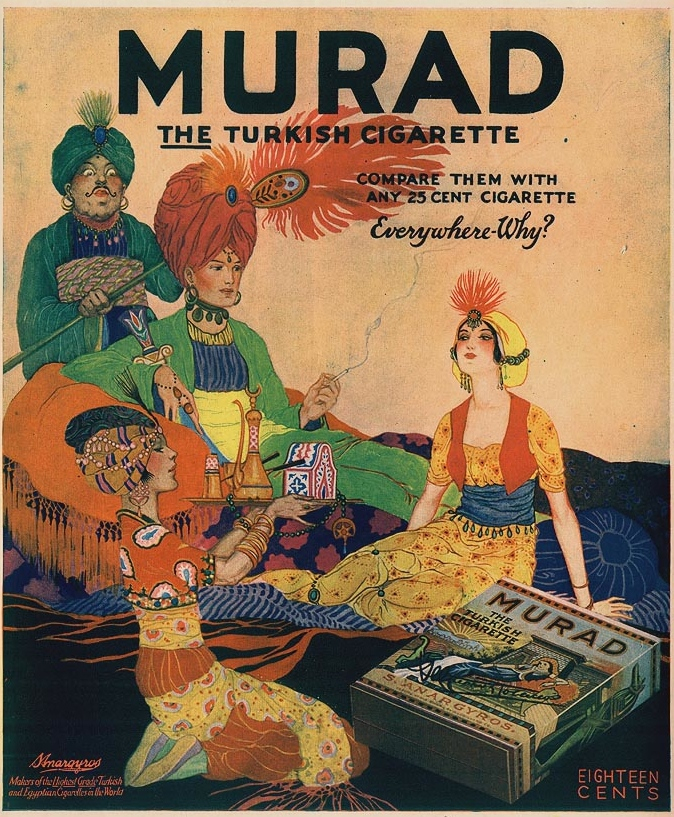

Images of Egypt, both ancient and contemporary, have found their ways into all aspects of Western life from opera (Giuseppi Verdi’s Aida), film (Theda Bara’s Cleopatra), art (the Art Deco movement), furniture design, and advertising (especially for Turkish cigarettes, such as the Egyptian Deities poster that so famously inspired Ruth St. Denis to explore Oriental themes in her dance performances). Ancient Egypt continues to fascinate, evidenced in the popularity of movies such as The Mummy franchise (1999 and 2001) and Stargate (1994); Pharaonic imagery in popular culture, such as Michael Jackson’s music video “Remember the Time” (1992); in the persistence of made-for-television documentaries ranging from National Geographic’s Egyptian Secrets of the Afterlife (2009) to the History Channel’s dubious Ancient Aliens (2010- ); and in architecture, such as I. M. Pei’s controversial glass pyramid at the Louvre in Paris. The legacy of Egyptomania and its resurgence have left a significant impact on the study of art, archaeology, race, gender, and national identity.

Egyptomania’s story begins with Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt in 1798, which was planned in great secrecy with the aim of, according to architectural historian James Steven Curl, “liberating Egypt from Ottoman rule and thereby menacing British India and threatening British notions of the balance of power.”³ The French also wanted to cut off England’s land route to India, which would deal a great economic and political blow to the British Empire, as well as occupy the shores of the Red Sea in order to cut through the isthmus of Suez (a feat that did not happen, but did eventually become the Suez Canal).⁴ The enormous and ambitious campaign included the Commission on the Sciences and Arts consisting of 167 intellectuals, led by Baron Dominique Vivant Dinon. As Napoleon’s troops battled the British, the Commission surveyed and recorded their observations and discoveries. Although the British defeated the French and forced them to relinquish collected antiquities—including the Rosetta Stone—under the Treaty of Alexandria, the Commission was allowed to keep its notes, drawings, and surveys.⁵ The Commission published their work, Description de l’Égypte, as installments between 1809 and 1826; it was an instant success. Despite being expensive, “few publications have enjoyed such an extensive circulation so quickly,” according to Curl.⁶ Curl also notes that Napoleon’s Egyptian campaign, and the “exact archaeological surveys of buildings caried out as part of that Captain, began the serious, scholarly side of the [Egyptian] Revival, as well as focusing attention on Egypt in a scientific, rather than a speculative, manner.”⁷ It also paved the way for further Western archeological exploration of Egypt, as well as tourism, ethnographic, and scholarly studies.

The influence of ancient Egyptian art and architecture continued through the 19th century. James Steven Curl says at this time “buildings, furniture, jewellery, paintings, ornaments, and even chimney-pots offer thousands of variations in the style,” and that Egyptian motifs “became fashionable in the Victorian periods largely through the drawings, writings, and photographs of travellers who ventured to the Nile.”⁸ The George Mason University website on Egyptomania says that the visual arts were “one of the most active sites for nineteenth-century American Egyptomania,” because so many of the discoveries were visual—such as ancient ruins, carvings, and hieroglyphs—greatly inspiring many painters and illustrators.⁹ Curl also notes that particularly between 1860 and 1900, especially from 1880, jewelry featuring hieroglyphs, scarabs, Pharaonic heads, and sphinxes were produced and survive today “in plenty.”¹⁰

At the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1889 the Pavillon Égyptien was built in the ancient Egyptian style, and the Palais de l’Égypte at the Exposition of 1900, featured a theater and a temple in Egyptian style.¹¹ Brier examines the proliferation of Egyptian imagery in cigarette advertisements; even though tobacco is native to the Americas, not the Middle East, the plant grows well in the Eastern Mediterranean. Egypt became home to a host of cigarette factories, and the parent companies exploited this connection, showing ancient Egyptian gods and goddesses, Egyptian-inspired architectural borders, and flappers in pseudo-Egyptian headdresses in their advertising.¹2

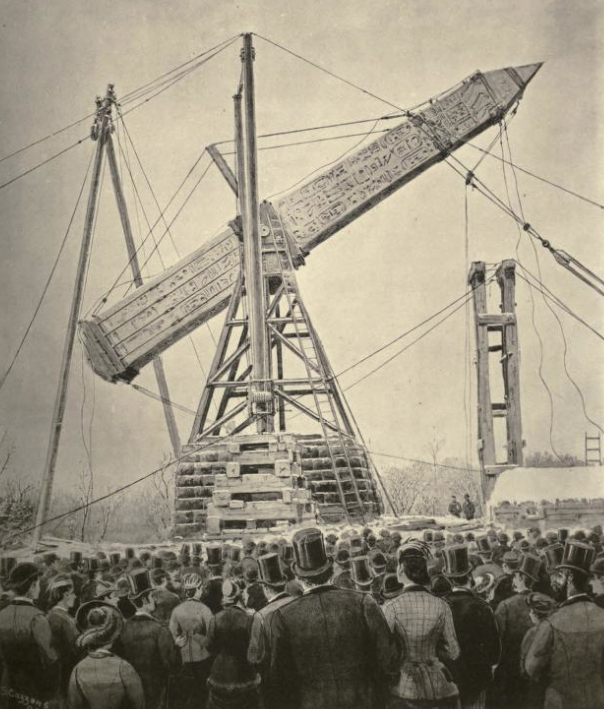

Several excavations and other events helped continue the simmering interest. The discovery of a rich horde of royal jewelry at the end of the 19th century spurred on fashion in Egyptian-themed jewelry, and the laborious installation of an obelisk in New York City brought the craze to the United States.¹³ The discovery of a cache of mummies in Deir al-Bahri, allowing people to gaze upon the faces of the warrior pharaohs of the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Dynasties—including that of Ramesses II, whom many believe to be the pharaoh of the biblical books of Exodus—made mummy-themed songs and sheet music—with titles such as “Mummy Mine” (1918) and “At the Mummies Ball” (1921)—all the rage.¹⁴

More than a hundred years after Napoleon’s expedition, archeologist Howard Carter’s 1922 discovery of Pharaoh Tutankhamun’s tomb spurred yet another revival of interest in all things Egyptian. A richer trove of antiquities had never, and has never since, been unearthed; neither ancient Egyptian tomb looters nor contemporary ones ever discovered the boy king’s burial chamber, leaving jewelry, furniture, food, beer, and, famously, the king’s mummy itself completely intact. Enterprising businesses adapted everything from mechanical pencils and perfume to talcum powder and pocket knives (and more sheet music) to cash in on the excavation.¹⁵ Brier, himself a collector of all things Egyptian, adds that ladies wore “Egyptian-styled dresses and Egyptian perfume.”¹⁶

The design and interest in the artifacts therein strongly influenced the Art Deco movement of the 1920s—named for the Exposition des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes in Paris in 1925—stimulating more “Egyptianising in architecture, furniture design, interiors, jewelry ceramics, and ornament,”¹⁷ as well as the Egyptian theater movement—ancient Egyptian-influenced interiors and decor in American movie houses. Many of the surviving theaters still bear names such as “The Egyptian” and “The Oriental.”¹⁸

Architectural historian Curl tells us that in addition to cinemas, a wide range of buildings such as factories and municiple headquarters, acquired “exotic plumage in the 1920s and 1930s.” Films, which had already explored Egyptian themes since the invention of moving pictures, also capitalized on the obsession. Some movies, such as The Mummy (1932), played on fears of a “Mummy’s Curse” or an act of revenge for disturbing the dead, while others glamorized Egypt, such as Theda Bara’s Cleopatra (1917) which played on the archetype of the exotic femme fatale.¹⁹ Egypt returned to Hollywood in the mid-20th century with Elizabeth Taylor’s Cleopatra (1963) is considered one of the ultimate ancient Egyptian epics—which also includes The Egyptian (1954) and, of course, Charlton Heston’s The Ten Commandments (1956)—encouraging further revival of interest in ancient Egypt.²⁰

Some scholars note that the allure of ancient Egyptian culture and its characteristic features is a result of cultural projection, revealing more about Western colonial anxieties and desires than about Egypt itself. Indeed, the fascination with Egypt as a timeless place of fantasy, mythology, curses, and queens, is an aspect of Orientalism as defined by Edward Said. Scott Trafton suggests that by the 1830s, mummies in fiction—often portrayed as villains—had become “more and more associated with a particular kind of either literal or symbolic revenge” for imperialism, slavery, and colonialism.²1 They also, according to Brier, allow us to confront death in a non-threatening manner.²² Egypt is also, as Brier notes, “a land far, far away and long, long ago,” as well as exotic, a location for physical and imaginary escapism.²³ Trafton adds that ancient Egypt is, in a way, poised between exotic and familiar, being not only “a third of the holy trinity of Greece, Rome, and Egypt,” and thus inherently Western, but also “an interracialized hallucination of sex, decadence, and degeneration,” a manifestation of the Oriental Other.²⁴

The content from this post is excerpted from The Salimpour School of Belly Dance Compendium. Volume 1: Beyond Jamila’s Articles. published by Suhaila International in 2015. This Compendium is an introduction to several topics raised in Jamila’s Article Book.

If you would like to make a citation for this article, we suggest the following format: Keyes, A. (2023). Egyptomania. Salimpour School. Retrieved insert retrieval date, from https://suhaila.com/egyptomania

1 Before then, of course, European civilizations had integrated ancient Egyptian architectural and visual motifs into their buildings and art and, in the case of Greco-Roman civilizations, into their religious and spiritual beliefs. See James Steven Curl, Egyptomania, The Egyptian Revival: a Recurring Theme in the History of Taste (Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press, 1994) for a thorough analysis of Egyptian influence on Western art and architecture since the fall of ancient Egypt. For a broader, historical look at the Egyptian influence in Western art and culture, see the very lucid and entertaining volume by Bob Brier, Egyptomania: Our Three Thousand Year Obsession with the Land of the Pharaohs (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013).

2 Brier, Egyptomania, 10. Brier also reminds us that even the ancient Greeks were fascinated with Egypt; when Greek traveler and writer Herodotus visited Egypt in 450 B.C., he notes, the great pyramids at Giza were already 2,000 years old—“about the same span of time that divides Herodotus and us.” Brier, Egyptomania, 17.

3 Curl, Egyptomania, 116-117.

4 Brier, Egyptomania, 42-3.

5 Ibid., 116-117.

6 Ibid., 119.

7 Ibid., 120.

8 Ibid., xviii.

9 Earl Shinn [“Edward Strahan”], Gerome: A Collection of the Works of J. L. Gerome in One Hundred Photgravures. Multiple Volumes (New York: Samuel L. Hall, 1881), accessed December 27, 2013, http://chnm.gmu.edu/egyptomania/sources.php?function=detail&articleid=24.

10 Curl, Egyptomania, 205.

11 Ibid., 206.

12 Brier, Egyptomania, 104.

13 Ibid., 108, 111-150.

14 Ibid., 156-9.

15 Ibid., 169-73.

16 Ibid., 11.

17 Curl, Egyptomania, xviii.

18 Stone, “Reverse Imagery,” 252.

19 Brier, Egyptomania, 179-81.

20 Curl, xviii.

21 Scott Trafton, Egypt Land, (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2004), 125.

22 Brier, Egyptomania, 9.

23 Ibid., 8-9.

24 Trafton, Egypt Land, 5.