The Tantalizing Tale of Bal Anat

Drawing from her experience as a performer with the Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus, belly dance innovator Jamila Salimpour formed Bal Anat as a truly unique and exciting entertainment experience. She named it for “Bal,” the French word for a dance gathering, and “Anat,” an ancient Mesopotamian mother goddess: Dance of the Mother Goddess.

Bal Anat Documentary

Entering in a flurry of finger cymbals and richly decorated costuming, the ensemble features at least 25 performers. Different dances are presented, each with its own character and origin. Innovative from the very beginning, Jamila Salimpour’s groundbreaking presentation was the first to integrate dancing with and balancing a sword. Soon thereafter, the sword became a quintessential belly dance prop.

Bal Anat stands at the crossroads of tradition and fantasy, but is always rooted in the traditional dances. The dances represent cultures of the Middle East, from North Africa, the Anatolian Peninsula, the Persian Gulf, and the Levant. Middle Eastern audiences have praised Bal Anat for its sentiment, reverence, and nostalgia.

Bal Anat Revival 2001

She also invites dancers with high-level certification in the Salimpour certification programs to contribute dances to the show. Recent performances have included elegant Khaleeji dance in elaborately embroidered gowns and the exciting Shamadan choreography by Suhaila Salimpour.

We welcome dancers in the Salimpour certification programs to join the global Bal Anat family. Dancers who hold certain certifications are invited to join. Bal Anat’s groundbreaking blend of the traditional, folkloric, and fantasy has inspired many. Moreover, it will continue to inspire generations of belly dancers.

Behind the Scenes at Bal Anat 2023

Bal Anat is the past, present, and future of belly dance

The Karshilama

When she performed in the West Coast nightclubs, Jamila Salimpour worked with many Turkish dancers from whom she learned and studied the Karshilama. She also studied about this dance in books and in whatever video she could find.

For Bal Anat, she choreographed a Karshilama based on the common and consistent movements and phrases from her Turkish counterparts in the nightclubs. While pelvic locks are definitely a part of Turkish dance and the Karshilama dance, Jamila’s Turkish peers were encouraged by club owners to not perform them. Pelvic locks were considered too vulgar for American audiences in the 1950s and 1960s.

When Suhaila revived Bal Anat, she re-choreographed the Karshilama adding her own cultural research of the dance. This included the addition of traditional pelvic locks that had been missing from the original Bal Anat choreography.

Bal Anat Mask Dance

The Mother Goddess, or Mask Dancer, is the iconic opening performance for Bal Anat, representing the Mother Goddess or Mother Earth. This dance was a later addition to the original Bal Anat that evolved from several sources. The mask dancer represents both the beginning of time as well as the present and future, forever watching over the earth and the continual renewal of life through birth and rebirth.

The Pink Ladies

The abdominal dancers, nicknamed the Pink Ladies, featured students who excelled at sultry taqsim movements. This was another of the fantasy dances, and Jamila costumed the cast in Cleopatra-styled wigs to give the feeling of an Egyptian court. Jamila eventually transitioned the Pink Ladies into the Mask Dancer solo which became the iconic first act of the Bal Anat Show.

Pot Dance

Jamila had long studied traditional dances from the Middle East and never found evidence of a traditional Egyptian pot dance. She observed a few nightclub dancers from the Middle East performing while balancing pots on their heads, but it seemed to be more of a gimmick. Jamila concluded, as supported by professionals such as Mahmoud Reda, that no traditional Egyptian pot dance existed.

Right as she was developing new material for Bal Anat, Jamila saw the movie Justine. The movie, based on a book by Lawrence Durrell published in 1959, premiered in summer 1969 and takes place in Egypt. About 50 minutes into the movie, the characters attend a party in during which pot dancers perform while accompanied by live drummers. The dancers were most likely Tunisian, and Jamila was inspired by what she saw.

Mahmoud Reda’s folkloric troupe had a pot dance. Mahmoud and his brother Fahmy founded the Reda Troupe in 1959. The group was sponsored by the Egyptian government to promote Egyptian folkloric dance on the theater stage to the world. Reda emphasized that they were inspired by folk dance and daily rituals which they supplemented and stylized for stage.

The pot dance, in particular, was inspired by women balancing water pots on their heads, but not by a traditional pot dance as no such dance existed. The folkloric troupes implemented a Western bodyline based on ballet with little hipwork. They were folk dancers and not belly dancers. Belly dance was not considered reputable and suitable for the folkloric troupe mission of gaining respect and recognition for Egypt throughout the world.

For her pot dance, Jamila focused on Egyptian belly dance. She used her step vocabulary and also studied and conferred with professional nightclub belly dancers from Egypt. Jamila’s choreography was initially performed by three dancers balancing large decorated gourds on their heads while they dance and performed floorwork. Suhaila’s revival and update of the Pot Dance expands the movement repertoire and typically casts a larger number of dancers.

Shamadan Dance

Shamadan for WeddingsThe Shamadan, a candelabra balanced on the head, has been used in traditional wedding processions (zeffas) and similar family celebrations from at least the early 1900s. Subsequently the Shamadan grew in popularity and by the 1960s and 70s. By this time, it became a standard for weddings in certain areas of Egypt and Lebanon.

Shamadan for Cabaret

In 1925, Badia Masabni opened the first of her famous Cairo nightclubs featuring belly dancers. It was in her clubs that the Shamadan had one of its earliest appearances in a cabaret setting. By the 1970s and 80s, the Shamadan became a regular feature often seen in Egyptian and Lebanese cabaret shows.

The staged dance has more freedom in music choice and stylization. Cabaret dancers often perform Shamadan to a “party” song that energizes the crowd. The stage allows the dancer creative liberties while still respecting and giving homage to the Shamadan’s traditional use in Arabic wedding and family celebrations.

Shamadan for Bal Anat

Both Jamila and Suhaila worked with professional dancers from Egypt and Lebanon who danced with the Shamadan in wedding processions and nightclub settings. Using what she learned from these dancers and additional research, Suhaila choreographed a Shamadan Dance for the Bal Anat 50th Anniversary World Tour.

The choreography is now one of the rotating pieces for the show. Suhaila’s Shamadan choreography is performed to Ya Ain Moulaytein, a Lebanese classic debke song. This song is a very popular and well-known standard throughout the Middle East, and this particular version evokes an earthy

Snake Dance

In 1969, Jamila rescued a snake from a magician whom she felt was mistreating the animal. At first, no one wanted to perform with the snake. Therefore, on her own, Jamila developed the snake dance by trial and error over time.

The snake dance was one of the fantasy dances and was not meant to represent a traditional Middle Eastern dance. Eventually, more dancers obtained their own snakes, and a mesmerizing group number was developed.

Audiences often commented about being hypnotized by the movements of the snake dancers who entered with the stylistic head slides and circles from Jamila’s step vocabulary. The snake dance is often done as a solo, duet, or group; dancers maintain and dance with their own pet snakes.

Khaleegi Dance

The Khaleegi choreography was created by Sabriye Tekbilek, one of Suhaila’s longstanding students who spent over a decade performing as a professional bellydancer in the Gulf Region. One of her specialties is Khaleegi dance. Khaleegi evolves with each generation. Sabriye’s choreography, written in 2015, demonstrates a modern Khaleegi style representing the current younger generation.

Sabriye also wrote a choreography (Leyla Khaleegi Choreography) for dancers to use in their performance sets.

For the musical accompaniment, Jamila accumulated a variety of instruments. These included finger cymbals, tambourines, wooden clappers, darboukas, mizmars, tabl beledi, dufs, and more. To expand the musician base, Jamila invited faire craftsmen to “sit in” on the performances and play mizmars. Ernie Fishbach had a flair for the music, and he became the backbone of the assembled band.

Jamila kept the heart beat of the group by drumming or playing finger cymbals. The performers stood in a semi-circle at the back of the stage, forming a sort of background chorus behind the featured dancers. The chorus would play finger cymbals or other instruments, zaghareet. Additionally, they served as a supporting and enthusiastic backdrop for the highlighted dance. The musicians were involved, as well, interacting with the performers.

By 2020, Bal Anat is performed typically in large theaters using selections from the Bal Anat: In the Beginning. This album was produced and published by Suhaila in 2002 featuring mastered versions of the traditional Bal Anat music. The music is supplemented by instruments played by the dancers and, when possible, musicians.

The water glass dance, where a dancer performs while balanced on three glasses, was another dance that Jamila added to the Bal Anat show. She was inspired by two primary sources. First, she studied drawings of Ghawazees dancing on wine goblets. Second, she observed Fatima Akef* who often danced on water glasses. Accordingly, Jamila was the first Bal Anat performer to dance on water glasses. In fact, she even combined the water glass and snake dance. Jamila taught her water glass method in her classes, and other dancers eventually rotated into that solo spot.

The water glass dance was an occasional act rather than a consistent part of every Bal Anat performance. Water glasses can break, and flooring for the dance needed to be conducive for scooting the glasses as well as level and clear. The current water glass dance is often performed in solos, duets, or trios; the updated dance features back bends, splits, and vibrations.

*Fatima was the sister of Naima Akef, one of the great Egyptian cinema dance stars of the 1940s. Fatima was a contemporary of Jamila’s who danced in West Club nightclubs. Fatima Akef had various elements in her dance including cameo appearances from her parrot, Lara, and dancing on water glasses.

For the original Bal Anat, Jamila added specialty acts including a sword swallower and two regular magicians: Gilli Gilli from Egypt and Hassam from Morocco.

The table balancing act was popular in the Greek night clubs in the 1970s, so Jamila added it to the show. Her performer, a Greek math professor from The University of California, Berkeley, would pick up a table with his teeth while balancing Suhaila on top of it.

The current Bal Anat features a wide variety of short acts including aerialists, contortionists, tumblers, and jugglers.

Inspired by a Jean-Leon Gerome orientalist painting, Jamila had a student perform while balancing a Turkish sabre on her head. Thus, one of the most popular fantasy dances in Bal Anat was created. Afterwards, single and double sword became standard props for dancers, especially in the United States. The same dancers performing at the Faire would include the sword routines in their cabaret routines in the clubs at night.

The popularity of Bal Anat’s sword dance spread like wildfire through the United States throughout the 1970s. Suhaila updated the sword choreography for Bal Anat using the sword dance from her iconic Percussion Show.

Tray Dance

Jamila’s first tray dancer was Meta who balanced a tray on her head throughout a performance that included floor work. Soon after, she was inspired by a Time-Life Moroccan cook book with a photo of male dancers dancing while balancing trays on their heads. As a result, Jamila was the first to introduce the male Moroccan tray dance to the United States.

Thereafter, Jamila continued using men in the soloist role until the Bal Anat Reunion of 1990, during which three of the surviving male tray dancers performed the dance as a trio. One of the trio, Tom “Rashid” Ryan, was the last tray dancer specifically picked by Jamila to be a Bal Anat tray dancer.

When Suhaila revived Bal Anat, Tom was once again cast in the role of the Bal Anat tray dancer, continuing until he passed away in 2012. Other men were appointed to the role. But for the 2018 Bal Anat 50th anniversary, Suhaila expanded the tray dance for a larger cast not based on gender.

The Ghawazee choreography was added to Bal Anat by Suhaila Salimour when she revived the troupe in 1999. Both Jamila and Suhaila studied the Ghawazee dancers extensively, examining every written detail and video clip available. Then, when Suhaila visited Egypt in 1981 and 1982, she saw the Ghawazee dancers several times. She made careful note of everything she observed in context and in relation to her research. Suhaila co-wrote the choreography with Tom “Rashid” Ryan who used Suhaila’s research and outline to form a first draft of a dance for Suhaila to finalize.

Tunisian Dance

Ghanima Ghiditana, one of Jamila Salimpour’s longstanding students and performers, visited Tunisia and did thorough research on Tunisian dance. She created a choreography representing her extensive studies. Therefore, Jamila featured Ghanima as the Tunisian soloist in Bal Anat. Ghanima developed her own representative costuming and selected the music. Her husband, one of the Bal Anat musicians, accompanied her on the tabl baladi.

Ghanima was also an instructor for Jamila. She also assisted in the creation of The Danse Orientale (a manual of Jamila Vocabulary Step Families and Steps compiled for an upcoming workshop) in 1978.

Male Dancers

Jamila was one of the first teachers to allow male dancers to attend her belly dance classes in 1973. For Jamila, it was important to find cultural relevance for men to perform belly dance. She felt supported to allow men in her classes when she found a male dancer amongst the images from the 1893 Chicago World’s Faire.

In Jamila’s classes, males underwent the same training as female students. The first male dancers were included as Moroccan female impersonators, which maintained a historical relevance. Later, male dancers were found in the tray dance, Ouled Nail Algerian dance, and the Turkish Karshilama.

With Suhaila’s revival of Bal Anat, inclusivity is an important part of the Salimpour School. Dancers are selected for roles based on their abilities, not their gender identity.

Algerian Dance

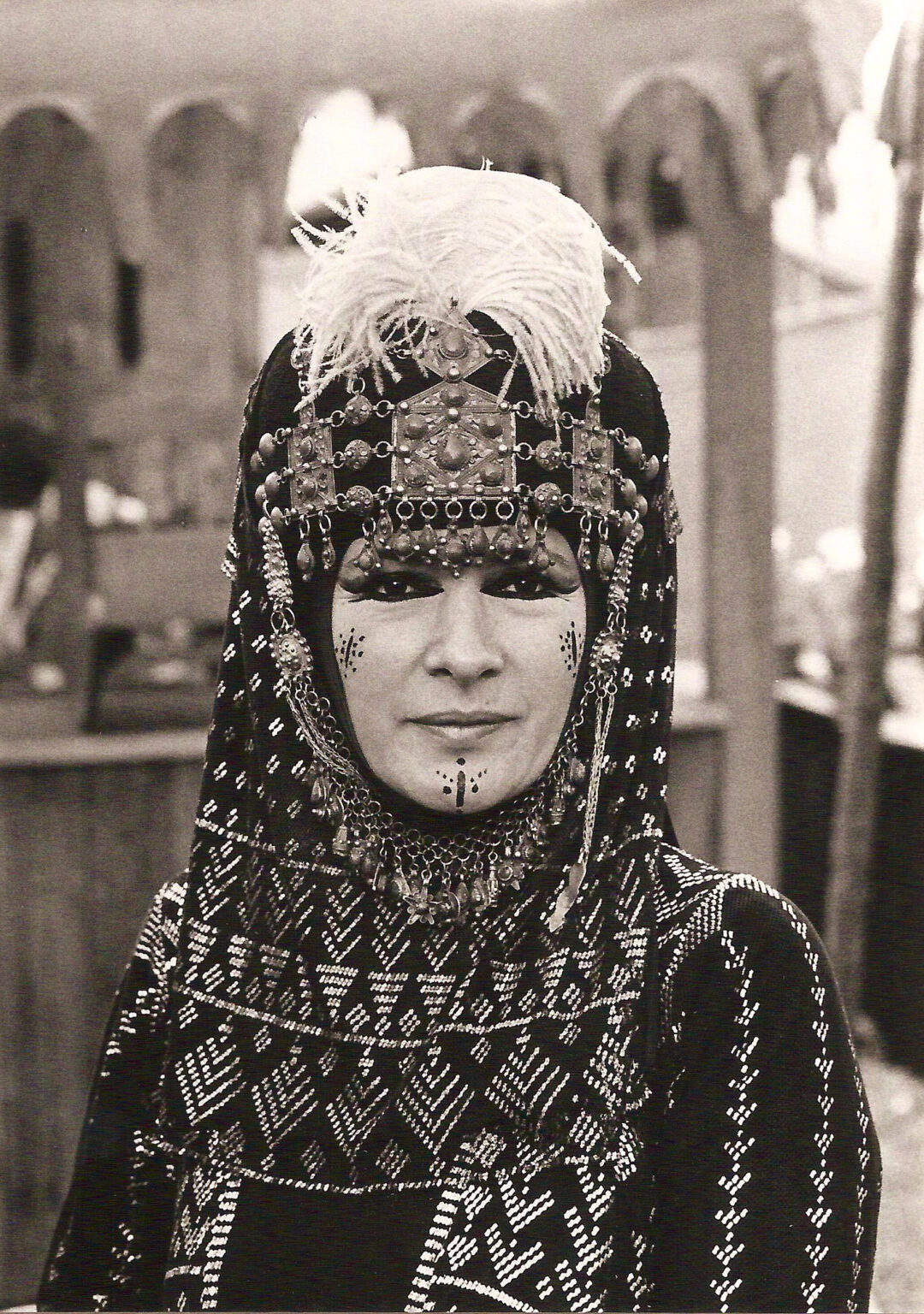

The Ouled Nail are a semi-nomadic people from the Algerian mountains. Some of the girls are trained from an early age to be entertainers and to dance as a means to earn money. Jamila Salimpour worked with several of these Algerian dancers who made their way to be professional belly dancers in the West Coast clubs. Initially, Jamila researched as much as she could about the Ouled Nail from books and film. And she studied her Algerian nightclub peers and learned from them not only the traditional Ouled Nail dance but also the staged version for the cabaret stage.

When she debuted her Algerian dance in Bal Anat, it was with the guidance and full support of these dancers. They even gifted her generic tattoos to be used in performance. Jamila styled her iconic headdress after the Algerian dancers. Jamila typically set the Algerian dance as a solo, and Don Iococa was the first dancer cast for the piece.

After taking over direction of Bal Anat, using her collected research with her mother, Suhaila expanded the choreography to include more dancers and traditional elements. While it might seem simplistic in comparison to some of the other Bal Anat dances, the Algerian dance is always an audience favorite.

Moroccan Dance

When performing in the West Coast nightclubs, Jamila Salimpour worked with several professional belly dancers from Morocco who incorporated traditional Moroccan dance movements in their performances that they further stylized and expanded for the cabaret stage. Using what she observed and learned from these peers as well as her own book and video research, Jamila choreographed a Moroccan dance for Bal Anat. In support of her presentation of their dance, her Moroccan dance peers gifted her generic tattoos for use by Bal Anat.

The Moroccan dance was one of Suhaila’s favorite dances as a young child. When Suhaila revived Bal Anat and created new choreography, she used her mother’s research as well as what she had learned and observed from adapting the traditional dance for stage.

After taking over direction of Bal Anat, using her collected research with her mother, Suhaila expanded the choreography to include more dancers and traditional elements. While it might seem simplistic in comparison to some of the other Bal Anat dances, the Algerian dance is always an audience favorite.

Fan Dance

The Fan Veil Dance is a fusion fantasy dance choreographed by Jane Chung How from Taiwan, who has extensive training in Chinese fan dancing technique and performance. Initially, Jane Chung How had performed a fusion piece for Bal Anat as a soloist before. Next, Suhaila requested that she create a piece specifically for use by Bal Anat beginning in 2012. Jane responsibly and seamlessly fuses traditional Chinese fan dancing with belly dance to create a lyrical choreography.

Finale Dancer

Bal Anat was not meant to be static or to show one snapshot in time. Instead it was and is a dynamic vehicle to show both historical and current themes in the dance. Jamila Salimpour’s intent was to begin Bal Anat with the Mask Dancer, representing Mother Earth. Then, the show would end with the Finale dancer, a classic but contemporary representation of belly dance.

Bal Anat maintains its roots, and remembers its origins but it continues to evolve. And the finale dancer is the symbol of the evolution of the art form.