While American audiences might have sought out the nightclubs to see women dance, there were many men who became involved with the dance and left their mark. Below we outline the lives of Ahmad Jarjour and Ibrahim Farrah, both of whom were renowned performers in their time. Ahmad was a prominent dancer and friend of the Salimpours; Ibrahim Farrah was one of the most influential dance instructors on the East Coast of the United States. We also discuss the community of male dancers in San Francisco in the 1960s and 1970s, and how the emergence of AIDS disrupted the lives of many talented and dedicated dancers. These men shaped American belly dance and have inspired a new generation of male dancers who have emerged in the early 2000s.

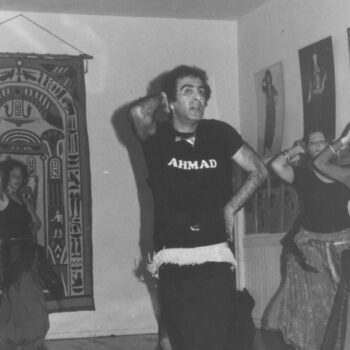

Ahmad Jarjour (ca. 1934 – 1989)

From his early childhood, Ahmad Jarjour (given name Russell) loved to dance. Born in Montreal, Canada, to Levantine immigrants (they referred to themselves as “Mesopotamians”¹), he worked in his father’s Middle Eastern grocery store that serviced the neighborhood Arab community. Like many young Arab boys, he participated in social dancing at family gatherings and parties with his father’s permission. Ahmad enjoyed mimicking the women in what we would consider belly dance moves. However, once he hit puberty, his family prohibited him from imitating the women, and he had to choose between adopting the more conservative male style of movement and not dancing at all. When he was sixteen, he decided that he would be a male Oriental dancer, and dance as a man.²

Jamila notes that Ahmad was a gifted performer with exceptional musicality; he loved classical Arabic music, as well as dancing and entertaining. Occasionally, he would teach, but his real love was performing. Jamila first saw Ahmad perform at the Bagdad Cabaret in San Francisco when she was still dancing there in the early 1960s. Later, she invited Ahmad back to San Francisco to teach a workshop at her studio, and she hosted him in her home. He spoke to her more about his life. In addition to her interview with Jarjour published in Habibi magazine, he also often talked to Jamila about his feelings of isolation and shame spurred by his desire to dance and by self-identifying as a homosexual man. Many family members ignored him, and they often left him at home with his great aunt because they were afraid he would embarrass them.

Ahmad knew he was disappointing his family, but his desire to dance was stronger, so he pursued dancing while suppressing his conflicted feelings. When talking to Jamila, he said that he considered himself a belly dance “groupie.” Two of his favorite dancers were the Quebec-based sisters Fawzia and Amira Amir, who performed on the East Coast. Ahmad Jarjour followed them, longing to dance like them or with them. After working for several years as a solo dancer, Ahmad created the first and original male-female dance duet with his first partner, Lisa. The duet starred with the Buddy and Mike Sarkissian music ensemble in Las Vegas, and the ensemble also toured together. He also worked with a dancer with the stage name of Saida Asmar for three months in Las Vegas.³

Jarjour had a difficult time in Las Vegas—Asmar hints that he had a penchant for over-partying⁴—and he sought help from Ibrahim Farrah, with whom he had developed a close friendship. Farrah helped Jarjour get back on his feet and refocus his career. Ahmad said that as he aged, he felt his greatest days were behind him because he could no longer dance as he did when he was younger. He confessed that quiet moments when he was not on stage, were hard for him and made him depressed as he was quick to begin contemplating his life. He tried various things to distract himself from these quiet moments. In his younger years, he enjoyed staying busy with parties and events every night and, as he got older, he used substances to help himself cope. When Suhaila, Jamila’s daughter, was twelve years old, Jamila asked Ahmad to teach Suhaila; he agreed but would delay actually meeting with her. He felt conflicted about teaching the already accomplished dancer: on one hand, he did not want to disappoint Jamila, but on the other, he admitted how emotionally difficult it would be for him to teach Suhaila.

Ahmad perceived Suhaila as a talented American teenager with family support who had had a much easier path than his own. He confided in Jamila, telling her that no one taught him, and his family hardly encouraged his chosen profession. He also admitted that he was jealous of Suhaila, as he saw her as at the beginning of her career while he felt he was at the end of his own. In light of his personal feelings, Jamila made a compromise: Ahmad agreed to allow Jamila to film him improvising to recorded music.

Ibrahim Farrah (1939 – 1998)

Ibrahim (Bobby) Farrah (born Robert Abraham Farrah) is considered by many to be the Father of Middle Eastern dance on the East Coast of the United States. Bobby, as his students and friends called him, was a highly renowned performer, choreographer, researcher, and teacher of the dance; Suhaila Salimpour refers to him as “Uncle Bob” in the editorial she wrote about seeing Nadia Gamal perform in Los Angeles in 1981.⁵ He believed belly dance to be an art form worthy of respect, and he endeavored to place the dance in the right situations and venues to earn that respect.

Farrah was a first generation American, the fourth child out of five, of Lebanese Christian parents who came to the United States in 1930. They settled in the mountains of Pennsylvania, which he noted were much like the mountains of his ancestors’ homeland in Lebanon.⁶ As a child, he enjoyed dancing at family gatherings, and he says that he learned the “art” of imitation, emulating his parents and elders. He learned most of what he first knew of Oriental dance, he says, from his mother, but he also observed the movements of his female relatives, mimicking and mentally cataloging their “feminine movement.” His mother called it the “Happiness Dance.”⁷

As a child in the 1950s, he was a devout Christian, choosing to attend services at the Evangelical United Brethren Church over those at St. Joseph’s, a Polish Roman Catholic church. He notes that part of the evangelical church’s appeal was the Gospel music, and he also would peep through the window of the local African American church to hear their Gospel music. As a teenager, however, he faced a personal conflict: his need for self-expression through movement, and his love of the church and its “prudish nature of forbidding dance.”⁸ For Bobby, dance was more important than devotion.

As a child of immigrants, he remembers living between two worlds, but that he felt restricted when he was between eight and ten years old, as keeping to tradition meant staying inside with relatives when he would have rather played outside. In high school and college, he wanted to be more “American” than Lebanese, but he noted later that he loved being Lebanese and American.⁹

In 1960, he saw a show at one of the nation’s first Middle Eastern nightclubs, Club Zara, in Boston, Massachusetts. After graduating from Pennsylvania State University in 1961 with a degree in History, Bobby traveled to Lebanon for six weeks and studied the dances there. When he returned to the United States, he obtained a job at the Library of Congress in Washington, DC. He spent much of his free time at the Port Said nightclub, observing the performances and atmosphere. One of the top dancers in DC at the time, Adriana, recognized his enthusiasm, befriended him, and encouraged him to perform at the Port Said.¹⁰ He obtained a job as a waiter at another of DC’s top nightclubs, Syriana, where Adriana also performed. In his autobiographical articles for his publication Arabesque, he says that he considered his dance career as beginning in Washington, DC, in the spring of 1964, when he was able to pay rent and bills, buy his own clothing and costumes, and feed himself from his dance earnings alone. Before then, he says, he was only employed part-time as a dancer. His decision to dance professionally, he says, “shocked and disappointed” his mother and his father was not quite so proud either. His parents, however, did accept his “peculiar” profession and grew proud of him and his accomplishments.¹¹ Shortly after, he began to dance professionally his dance partner, Emar Gemal. Together, they toured the United States for three years, performing on the nightclub circuit, in both Middle Eastern and American venues. Bobby took advantage of his work, observing the other performers in the nightclubs, just as Jamila Salimpour did in her early days. He also studied the movements of dancers in Middle Eastern films. While on the road, Bobby sought out dance schools, taking classes in everything from ballet and jazz to juggling and acrobatics.¹²

Bobby moved to New York City in 1967, and there he taught at the International School of Dance at Carnegie Hall, a position he held for two years. In 1969, he opened his own dance school in a loft on 72nd street in Manhattan, in which he taught regularly for two years. He also formed his own dance company, the Ibrahim Farrah Near East Dance Group, which was sponsored temporarily by Doris Duke’s¹³ Near East Dance Foundation. With his dance company, Bobby took the dance out of nightclubs and on to reputable theater stages, performing “religious, secular, social, and historical” dances from the Middle East, accompanied by live music.¹⁴ In his lifetime, he performed twice at Carnegie Hall,¹⁵ an accolade that few other Oriental dancers can claim. His instruction influenced hundreds of dancers, affectionately known as “Bobby’s Girls,” and dancer Amaya credits him with introducing the cane dance and Pharaonic stylization to the United States.¹⁶

In 1968 and 1971, he returned to the Middle East, partially funded by Duke’s philanthropy, to learn more about Oriental and folk dance, as well as Middle Eastern culture. He also conducted archival research, reading travelers’ accounts and studying historical images of dances. He attended numerous family gatherings, festivals, concerts, and nightclubs, observing the movements and stylizations. When he was in Lebanon in 1968 he first saw Nadia Gamal perform in person. At the time, she was one of the first Oriental dancers to become an international star. She and Bobby became close friends, and she was an inspiration and mentor to him until her death in 1990. Oriental dance scholar Michelle Forner says that their “strong bond is seen in much of his dance aesthetic and teaching style.”¹⁷

In 1974, Bobby started teaching with Paul Monty’s International Dance Seminars—day-long conventions with several workshop instructors—and the response was overwhelmingly positive, as by this time, the belly dance craze had taken hold in the United States. He then started teaching nationally 1975, and he noticed that despite their enthusiasm and desire to learn, many dancers knew very little about belly dance or Middle Eastern culture. In response, he published the first issue of Arabesque magazine in 1975,¹⁸ a bi-monthly publication that focused not only on belly dance and Middle Eastern folk dance but also other ethnic dance forms such as Kathak and Flamenco. In an interview with Adam Lahm, Bobby said that apart from “how-to” books, there was very little published material on Oriental dance and its related disciplines. He said that fellow instructors of belly dance were “saying that they would be called on to conduct a lecture, go to the library for reference material, and find zilch,” and this dearth of information was “a universal problem througout the country.”¹⁹ Arabesque, like its West Coast counterpart Habibi, more than forty years after its first issue, is still considered an authoritative source on Middle Eastern dance. He continued to publish Arabesque until 1997; he passed away in 1998 in Manhattan at the relatively young age of 58.

Farrah believed that students of Middle Eastern dance had to understand the culture and music of the region, but he was not against abstract and creative interpretations.²⁰ He felt that dancers must express a wide range of emotions in their performances, lest they appear “monochromatic and rather pointless.”²¹ Michelle Forner, in her biography of Bobby for Habibi magazine, said he was “knowledgeable, articulate, and controversial,” and that “he influenced almost every facet of the art and business of contemporary Middle Eastern dance.”²²

The AIDS Epidemic and the American Male Belly Dancer

In the United States, the tale of the male dancer is first one of liberation and celebration, but also of loss. San Francisco has long been a destination for people seeking artistic and expressive freedom, and its permissive culture and celebration of “free love” made it especially attractive in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The 1970s heralded a new era of liberation, political clout, and “Gay Pride” in San Francisco, particularly in the Castro District, which became a magnet for young gay people across the United States.²³

At first, Jamila did not allow men in her classes. She had seen Ahmad Jarjour perform Oriental-style dance at her Bagdad Cabaret, but she considered Ahmad to be an anomaly. She had also seen the works of Muhammad Khalil and Mahmoud Reda, but she considered these performances to be folkloric, not belly dance. A few years after Jamila saw Ahmad, a young John Compton went to the Northern California Renaissance Pleasure Faire and saw a performance by Bal Anat. He immediately wanted to study with Jamila Salimpour, and sought out her studio in San Francisco. Jamila, however, would not allow him to take classes, because at the time, she taught only women. She felt that until she had historical and cultural evidence of male dancers, she could not admit men. John was persistent; he would sit outside the door to Jamila’s class, listening to the music and whatever instruction he could hear.

In the meantime, Jamila researched to find any historical substantiation to allow men in her classes. Once she came across the photograph of Mohammed, a Syrian dancer at the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago, she knew there had indeed been historical precedent for male belly dancers. She had the photo enlarged and framed, hung it on her studio wall, and after, allowed John, and other men, to join her classes. After John, many other young men came to her classes and performed with Bal Anat; several other belly dance groups started by Jamila’s students also included male performers. The permissive environment of San Francisco in the 1970s, with its emphasis on individuality and self-expression for peoples of all genders and sexual orientations, contributed to the increase of male belly dancers, including the belly dance troupe Al-Fellahin, also known as the Castro Street Belly Dancers, which featured five male bellydancers in its original membership.

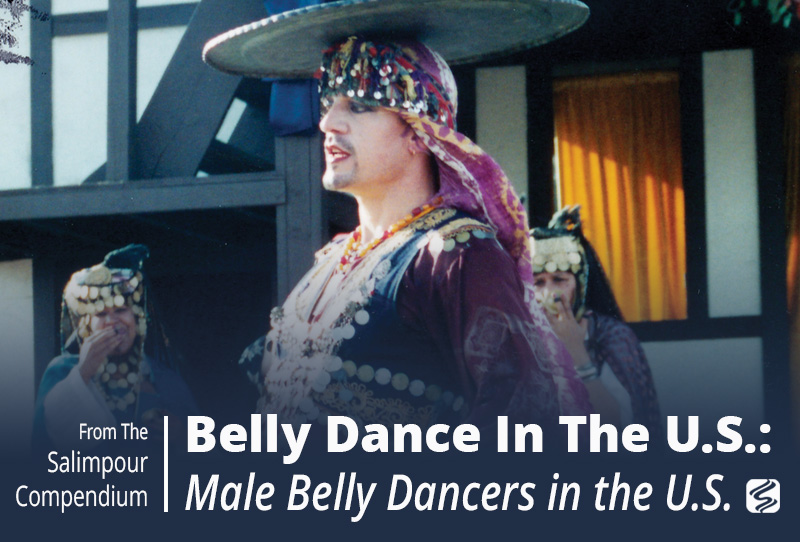

John, along with Darius (also known as “Chipper”), Jay Goodman, Don Ioca, and Rashid (Tom Ryan)²⁴ became some of the first American male belly dancers, and, as her article says, Jamila called them khawal. John first appeared with Bal Anat as a Moroccan female impersonator and dancing girl. Later, he performed as one of the tray dancers, modeling his choreography and costuming after the previous female tray dance soloists in Bal Anat. Darius and Jay Goodman followed as tray dancers, and Don Ioca performed as an Algerian Ouled Nail. In the mid-1970s, Rashid became the last male tray dancer to be selected by Jamila Salimpour.

However, in the early 1980s, homosexual men (as well as intravenous drug users and people who had received blood transfusions, such as hemophiliacs) started showing symptoms of various diseases that otherwise healthy people would not contract, such as Kaposi’s Sarcoma (a kind of skin cancer found mostly in older men of Mediterranean descent) and certain kinds of pneumonia, particularly in the United States’ largest cities: New York, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. These illnesses typically only affected those with compromised immune systems, not young, healthy men and women. A majority of the cases were gay men, so doctors and researchers called the disease GRID: Gay-Related Immune Deficiency, although not all patients with similar symptoms were homosexual. The media, fueling already rampant homophobia, called the disease “gay cancer.” After several intense years of study and research, epidemiologists and virologists identified the culprit as HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus), and the disease it caused being AIDS (Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome).

HIV/AIDS further stigmatized the gay community, which had already been fighting homophobia and other forms of marginalization. In the time between the emergence of HIV and the discovery of it being a sexually transmitted infectious pathogen, the gay community in San Francisco (and in many of the US’ large cities) lived in fear and mourning. Many of the greatest male dancers had to go “underground,” and many of them contracted HIV. Nearly all of the best-known male dancers of the 70s eventually succumbed to the disease. The development of medications such as AZT helped prolong the lives of some of them; however, some died before benefitting from their use. Others, such as John Compton²⁵ and Tom Ryan, lived for more than a decade with HIV, but by 2013, both had succumbed to complications from the illness. Nearly all of the male dancers with Bal Anat fell victim to AIDS, signaling the end of a dance era. It would not be until 2013 that a new tray dancer would be selected for Bal Anat.²6

The content from this post is excerpted from The Salimpour School of Belly Dance Compendium. Volume 1: Beyond Jamila’s Articles. published by Suhaila International in 2015. This Compendium is an introduction to several topics raised in Jamila’s Article Book.

If you would like to make a citation for this article, we suggest the following format: Keyes, A. (2023). Male Belly Dancers in the United States. Salimpour School. Retrieved insert retrieval date, from https://www.suhaila.com/male-belly-dancers-in-the-united-states

2 Ibid., 53.

3 Andrea Takish, “The Gilded Serpent presents… The North Beach Memories of Saida Asmar,” The Gilded Serpent, accessed January 3, 2014, http://www.gildedserpent.com/articles5/northbeach/people/andrea.htm.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibrahim Farah and Suhaila Salimpour, “I Remember Nadia,” Arabesque 16:3 (1990) 9.

6 Ibrahim Farrah, “A Dancer’s Chronicle…The Lebanese Chapters,” Arabesque 16:5 (1991) 9.

7 Ibrahim Farrah, “A Dancer’s Chronicle…The Lebanese Chapters,” Arabesque 17:6 (1992) 12-3.

8 Ibrahim Farrah, “A Dancer’s Chronicle…The Lebanese Chapters,” Arabesque 19:2 (1993) 14.

9 Ibrahim Farrah, “A Dancer’s Chronicle…The Lebanese Chapters,” Arabesque 17:5 (1992) 13.

10 American Belly Dance Legends, directed by Maria Amaya, (Albuquerque, NM: Amaya Productions, 2010), DVD.

11 Ibrahim Farrah, “A Dancer’s Chronicle…The Lebanese Chapters,” Arabesque 18:1-5 (1993) 8.

12 Michelle Forner, “Ibrahim Farrah: 1939-1998, Artist, Educator, Ethnologist,” Habibi 17:1 (Spring 1998), accessed January 3, 2014, http://thebestofhabibi.com/vol-17-no-1-spring-1998/ibrahim-farrah/.

13 Doris Duke was an American tobacco heiress (the same family that funded the creation of Duke University in North Carolina) who took quite an interest in Middle Eastern arts, and became a prominent patron of Oriental dancers in New York City.

14 Forner, “Ibrahim Farrah.”

15 Farrah, “A Dancer’s Chronicle,” 18:1-5, 8.

16 American Belly Dance Legends.

17 Forner, “Ibrahim Farrah.”

18 Ibid.

19 Adam Lahm, “Ibrahim Farrah: A Commitment to Dance, a Commitment to Life,” Arabesque 5:2 (1979): 4.

20 Ibid., 32.

21 Farrah, “A Dancer’s Chronicle,” 17:6, 13.

22 Forner, “Ibrahim Farrah.”

23 “We Were Here: Timeline,” PBS, accessed November 29, 2013, http://www.pbs.org/independentlens/we-were-here/timeline.html.

24 Jay spent time living with the Tuareg Berbers (also known as the “Blue People”) in North Africa, where participated in the tribe’s guedra (blessing ritual), and was included in the successive line of women who lead the ritual. When he returned to the United States in the late 1970s, he demonstrated what he learned at Jamila’s studio on Broadway. Later, he opened a store in San Francisco featuring his clothing designs. Don was known for his taqsims and fusion of belly dance with folkloric; later, he became a Buddhist monk. Rashid was first cast as a Karshilama dancer in Bal Anat. When Suhaila took over direction of Bal Anat in 1999, Rashid continued as the male tray dancer until he passed away in 2012.

25 Najla Marlyz, “John Compton on Broadway,” The Gilded Serpent, accessed November 29, 2013, http://www.gildedserpent.com/articles6/northbeach2/johncompton.htm.

26 In the early days of Bal Anat, there were sometimes more than one male tray dancer, but each dancer was personally chosen by Jamila herself. After Suhaila Salimpour revived Bal Anat in the 1990s, Jamila, Suhaila, and Rashid sought an additional tray dancer; Rashid had hoped to be able to perform a duet. The three of them, however, felt that they hadn’t seen anyone suitable for the role.