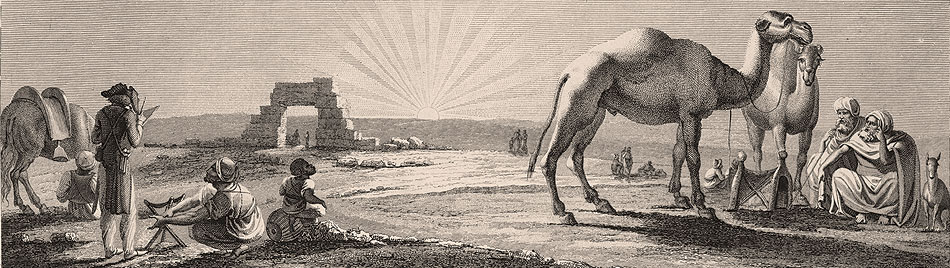

Egypt in particular was a popular destination with its ancient antiquities and lively bazaars and “exotic” people. Scholar Derek Gregory’s in-depth essay on European travel writers in Egypt notes that many described Egypt as a “theater,” as an “illusion,” and something to be observed. For Europeans, he notes, the “costume” of the Egyptian people “scripted the scene as theatre and constituted local people as actors and tourists as audience.” Gregory also says, “the parade of ethnographic types fed off one another and turned Cairo into an entertainment as well as an exhibition,” and as a place that could be “deciphered by the educated reader.” He also notes that Edward Lane’s Manners and Customs of the Modern Egyptians “provided the model for other travel writers” who “transformed Cairo into an open-air gallery” for their own observation, entertainment, and fascination, as well as “an exotic, supposedly ‘timeless’ and hence ‘authentic’ Orient which remained ‘unspoiled’ by the invasions of modernity.” ³

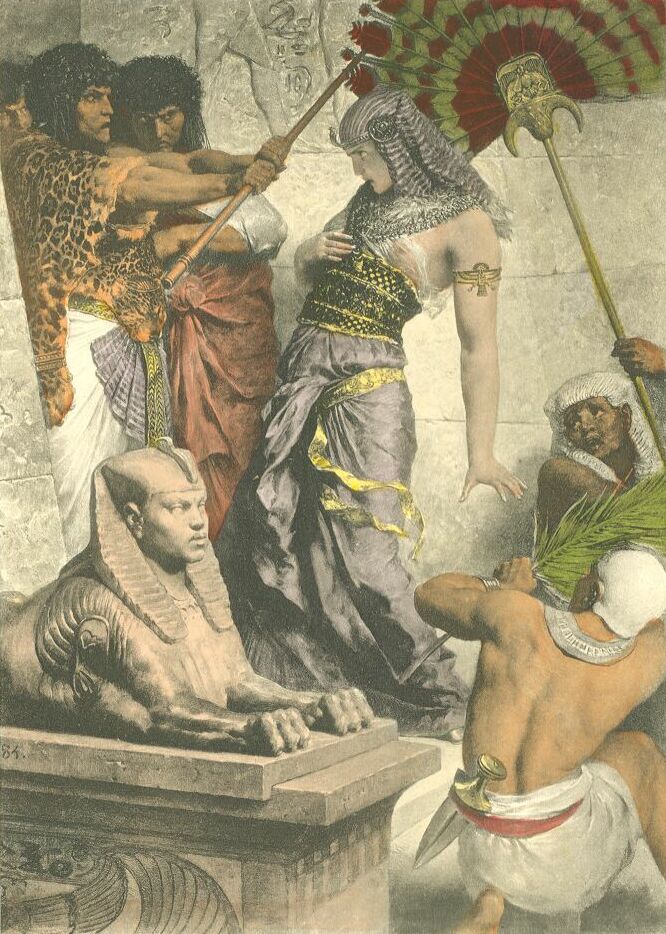

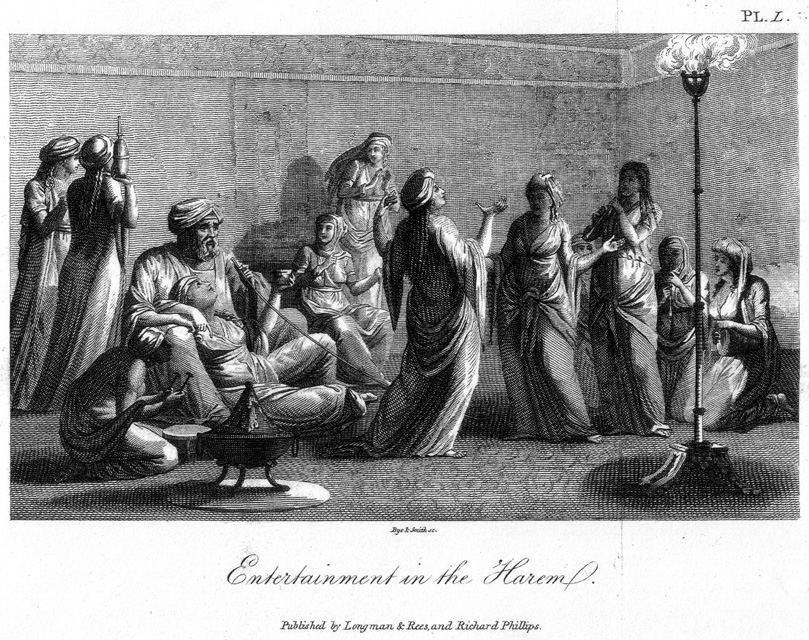

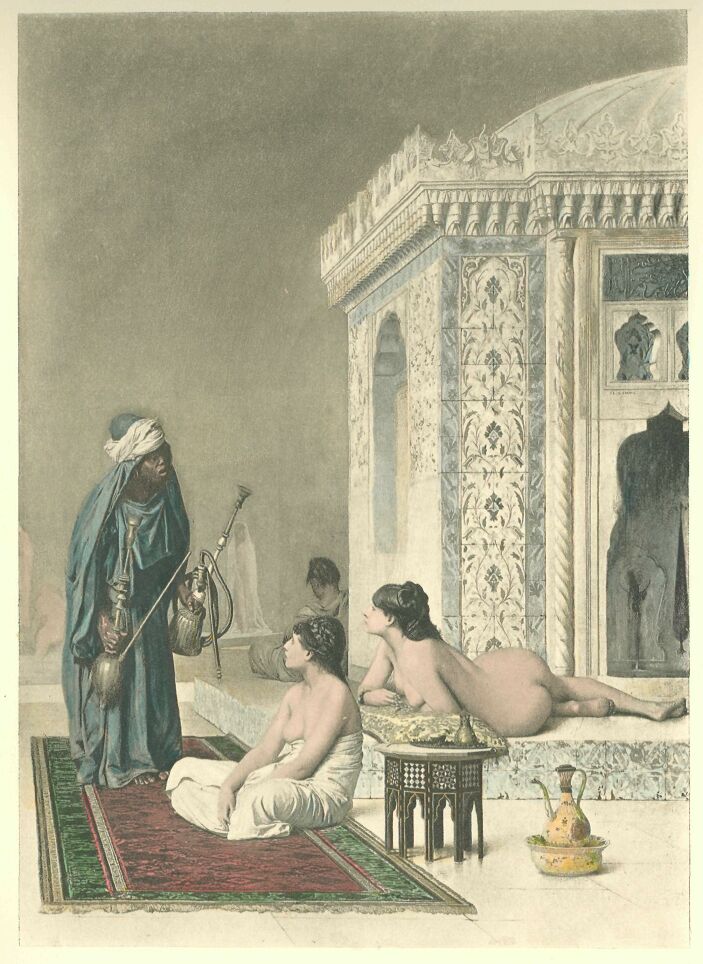

Racism and sexism colored much of these travelers’ accounts of life in the “exotic Orient,” and they often emphasized the “imprisonment” of women in harems, the “depravity” of the “Oriental,” and the backwards timelessness of the Middle East itself. Accounts dating back to the 17th century reveal these prejudices, which were exacerbated by the development of Victorian prudishness in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Scholar Judy Mabro says that Europeans often knew and cared very little about the economics and politics of the countries they visited, and were more interested in “finding links with the past to demonstrate that Oriental society had not changed for thousands of years—or proving that Islam was the cause of all the misery around.”⁴ Mabro also says that European attitudes towards the people of the Middle East were “shaped by ethnocentricity and a belief in the superiority of the European race,”⁵ an attitude buttressed by the Industrial Revolution and the (mis)interpretation of Charles Darwin’s revolutionary work, The Origin of Species (published in 1859) as justification for the popular belief that some races (Western and European) were biologically and evolutionarily superior to others (basically everyone not Western or European). John Foster Fraser, in his description of a North African woman, comments on her “exotic loveliness” but also as possessing a “little Oriental brain.”⁶ Mabro also notes that 19th-century travelers (both male and female) also wrote obsessively about the harem and veiling; images of prisons and shackles were used throughout their texts, regardless of the reality of the situation.⁷

Like Jamila herself, many people were first exposed to the “exotic Orient” through accounts of travelers, military officers, and family members who had visited the region. Before Oriental dance arrived in the United States at grand expositions in Philadelphia and Chicago, it lived in the words of European and American travelers.

Both men and women adventurers, writers, and artists traveled to the Middle East—some out of curiosity and others to “escape from reality”¹—and preserved their experiences, observations, and perceptions in letters sent back to their friends and family and books published upon their return. Scholar Derek Gregory says that by the end of the 1800s, it seemed as if “every European or American traveler to Egypt had felt compelled to write about the experience.”² Those writings helped spark interest not only in the Middle East itself, but future ethnologic and anthropologic study of the region and its people.

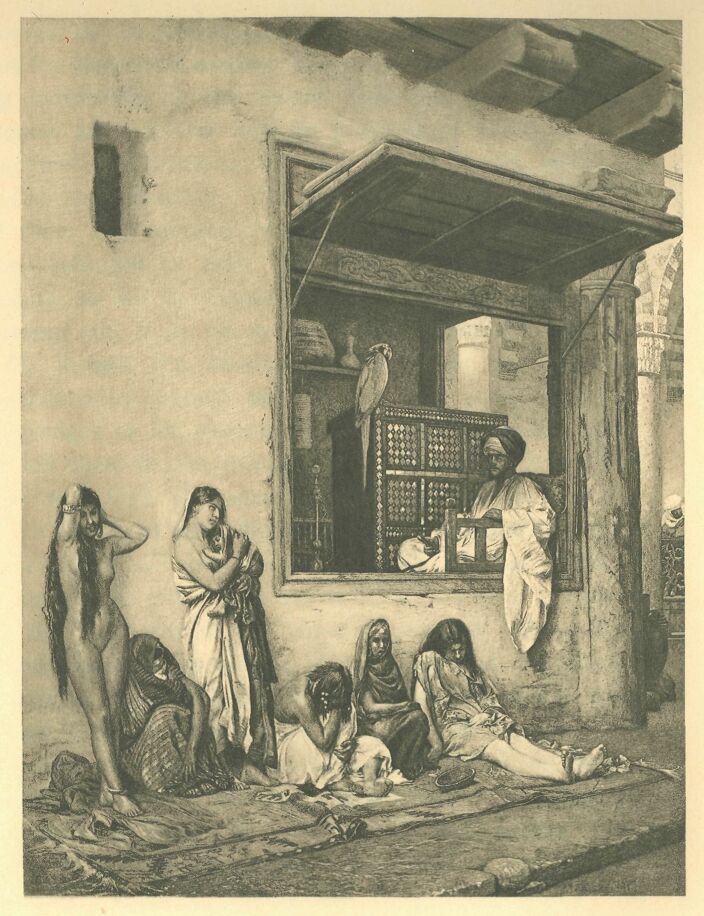

Many European travelers focused heavily on Middle Eastern women, analyzing their appearances as though they were static works of art rather than living human beings. Female travelers were often given tours of harems, and men were showed the way to brothels, or, at least, what they thought were brothels.⁸ Some men, such as Gustav Flaubert, wrote freely about their experience of being “customers,” while others merely hinted at their “sexual adventures.” Indeed Flaubert’s night with the ghawazi dancer and courtesan Kutchek Hanem is perhaps the most famous and most intimate account of interactions with the ghawazi, but many others also wrote about their observations and experiences with the dancing girls of Egypt.⁹

Belly dance was established in the popular imagination in the West through travelers’ accounts, which emphasized the perceived lewdness of the dance. Mabro caveats that when we read the “allegations of gross immorality” described in the writings of early European travelers, we should remember that “the women who appeared to have the most freedom and were most visible to travelers, were the prostitutes and public dancers.”¹⁰ Turkish dance scholar Metin And notes that these travelers gave considerable attention to dance performances in their books, and, although they emphasized the “slack morality and obscene character of the dancing, they could not hide in their descriptions the breathless interest they took in these performances.”¹¹ Lady Mary Wortley Montagu wrote in one of her letters that the dancers she observed in Anatolia performed in such a manner that even “the most rigid prude upon earth could not have looked upon them without thinking of something not to be spoke of.”¹² Another traveler in Tunis describes the “hip-dancing, which means the swaying of a mountainously fat body” by a group of Jewish dancers as “disgusting.”¹³

It should be noted, however, that a few women travelers, such as Lady Montagu and Lucie Duff Gordon, wrote more balanced and objective observations (relatively) of the people they encountered than male travelers did. While in Turkey, Lady Montagu—who was accompanying her English ambassador husband there in 1716—had free access to Turkish women and the women’s baths. She notes that “wealthy Muslim women owned and controlled their properties even when married,” making them “much better placed and had less to fear from their husbands than there sisters in the Christian world” at the time.¹⁴ In response to a majority of male travelers commenting that Middle Eastern women were “old hags at thirty,” Lucie Duff Gordon tries to give a more objective view: “I have now seen a considerable number of Levantine ladies looking very handsome, or at least comely, till fifty.”¹⁵ She also wrote in 1864, criticizing other travel writers’ bigotry, “Have we grown so very civilized […] that outlandish people seem like mere puppets, and not like real human beings?”¹⁶

Today, we can read these letters, observations, and essays with a greater awareness of the racism, sexism, and bigotry that informed many European opinions of Middle Eastern people in the 18th and 19th centuries. Regardless of their biases, these accounts continue to be valuable resources for those of us seeking out the origins of our dance form, and European attitudes toward it. Even today, scholars studying the ghawazi and other public dancers in Egypt continue to reference the writings of scholar-adventurer Edward William Lane’s An Account of the Manners and Customs of the Modern Egyptians, in which he describes his observations from living in Egypt in the mid-1830s.¹⁷

The content from this post is excerpted from The Salimpour School of Belly Dance Compendium. Volume 1: Beyond Jamila’s Articles. published by Suhaila International in 2015. This Compendium is an introduction to several topics raised in Jamila’s Article Book.

If you would like to make a citation for this article, we suggest the following format: Keyes, A. (2023). Western Travelers in the Middle East. Salimpour School. Retrieved insert retrieval date, from https://salimpourschool.com/

1 Mabro, Veiled Half-Truths, 34.

2 Derek Gregory, “Scripting Egypt: Orientalism and the Cultures of Travel,” in Writes of Passage: Reading Travel Writing, ed. James Duncan and Derek Gregory (London: Routledge, 1998), 115. This essay is an illuminating in-depth analysis of how European travellers in the 18th and 19th centuries perceived Egypt and the surrounding areas.

3 Ibid.

4 Mabro, Veiled Half-Truths, 160.

5 Ibid., 6.

6 John Foster Fraser, The Land of Veiled Women: Some Wanderings in Algeria, Tunisia and Morocco. (London: Cassell and Company, 1911), 165-166, accessed December 28, 2014, https://openlibrary.org/books/OL6536600M/The_land_of_veiled_women.

7 Mabro, Veiled Half-Truths, 5.

8 Ibid., 98.

9 Gregory, “Scripting Egypt,” 143.

10 Mabro, Veiled Half-Truths, 6.

11 And, A Pictorial History of Turkish Dancing, 138.

12 Montagu, Letters, 195-196.

13 Douglas Sladen, Carthage and Tunis, Vol II, (London: Hutchinson, 1906), 481, 483, accessed December 29, 2014, https://openlibrary.org/books/OL7195788M/Carthage_and_Tunis.

14 Montagu, Letters, 247.

15 Lady Lucie Duff Gordon, Lady Duff Gordon’s Letters from Egypt, (London: R. Brimley Johnson, 1902), 20, accessed December 30, 2013, http://books.google.com/books?id=AvhEAAAAIAAJ&.

16 Gordon, Lady Duff Gordon’s Letters, 112.

17 Shay and Sellers-Young, introduction, 6.