The Veil as Dance Prop

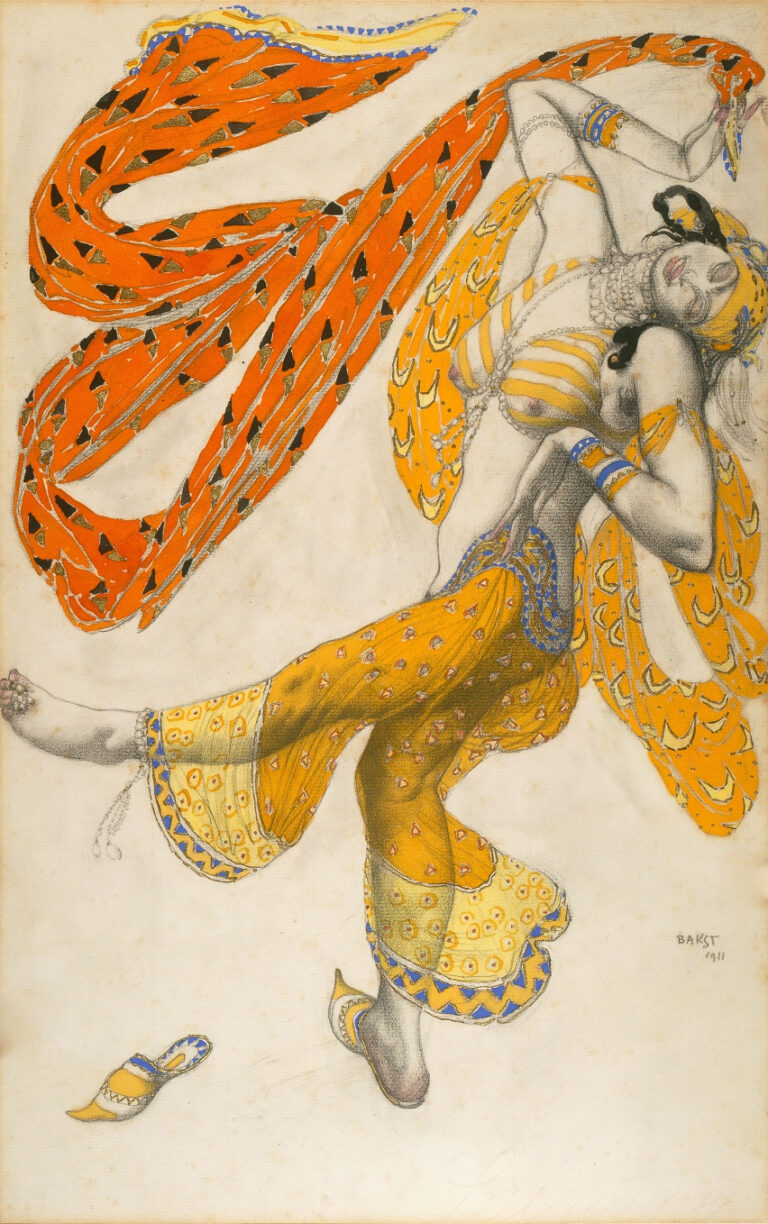

The veil as we know it in belly dance—a three-to-four yard of lightweight fabric used as a prop—is a recent invention. In her article, Jamila introduces us to the practice of full-body veiling in ancient classical societies, but the current practice of using a veil in Oriental dance performances is relatively new. The use of fabric as a prop outside of dance, however, dates back a bit further. 19th and early 20th century paintings and photographs of Arab women posing scarves, shawls, and head coverings¹ may or may not have been accurate depictions of these women, but merely posed for a sensational photo.² Dance researcher Laurel Victoria Gray notes that the dancers of the Ballets Russes used veils in some of their “Oriental” choreographies such as Salome and Cléopâtre, “perhaps borrowing the idea from the Caucasus” or inspired by Oscar Wilde’s Salome. She also notes that while small scarves are a common element in some folk dances, such as Azeri and the dances of the Turkish çengi, veils themselves are rare as a dance prop; if they are used, they are attached to a small pillbox hat, and primarily in Central Asia.³

Oriental dancers did not start using veils until the 1940s.⁴ In a conversation with Samia Gamal and Tahia Carioca, dancer and historian Morocco (Carolina V. Dinicu) says that the two dancers told her that King Farouk of Egypt hired Russian ballet instructor Madam Sonia Ivanova—who was already in Egypt teaching the king’s children—to instruct Samia to carry a lightweight length of fabric for her entrance to improve her arm carriage.⁵ Gray asserts that maybe Ivanova herself found inspiration in the “Oriental” dances of the Ballets Russes.⁶ American dancers saw Samia use this new prop in Egyptian films such as Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves, and they incorporated it into their own routines.⁷ American nightclub dancers expanded on the idea in the 1960s and 1970s, performing to an entire song while gracefully manipulating the veil around themselves. The veil dance then became an integral part of the multi-part routine, and is now considered an essential element of classic American belly dance, with dancers using the prop “to create various head and body wraps.”⁸ In a typical American-style belly dance show, the dancer enters with the veil artfully tucked into her costume and wrapped around her body. She wears it during her entrance piece (a fast-tempo song), and then removes it and uses it as a prop during the first slow song (usually a taqsim or çiftetelli). When the slow song is finished, the dancer discards it for the rest of the show. It is also possible that the dancing with a veil also has roots in the idea of Salome’s (Wilde’s) “Dance Of The Seven Veils,” Loïe Fuller’s performances with countless yards of fabric, and in Hollywood’s images of the ancient Orient.

Egyptian dancers, however, rarely use the veil for anything other than their entrance, after which they discard it at the edge of the stage. Dance researcher and instructor Morocco notes that people from the Middle East are unlikely to understand American-style veil dancing as they associate the removal of the fabric and reveal of the costume (and skin) underneath with a kind of striptease. She says that this reason is why dancers in the Middle East dance only briefly with it.⁹

The veil as a dance prop has become a subject of discourse in dance and performances studies with some scholars identifying it as an Orientalist symbol or as a means for Western dancers to identify with an imaginary and exotic “Orient.” The veil, because of its Western association with women, concealing, oppression, and of Islam itself, is a subject ripe for postmodern critique. Donnalee Dox says, “the costume veil allows Western performers to stand in for a ‘real’ Middle East, although it is essentially a Western innovation.” She also says that it is a “marker” of representing a cultural alternative, “veiling a dancer’s Western identity with a fantasy of Otherness.” Dox goes so far as to say that the removal of the veil during the taqsim or çiftetelli is “an act of liberation,” as the dancer sheds what many Westerners view as a physical representation of Islamic and male oppression.¹⁰ Andrea Deagon notes that the concealing/revealing qualities of the costume veil, as well as its association with the sexualized character of Salome, contributes to the image of belly dance being a sort of “exoticised striptease.” She also says that the veil, as a feminine object, came to signify the dark, “effeminacy, sexual degeneracy, softness, penetrability, and plunderable defeat,” in opposition to the “more culturally approved values of masculine, open, and light.”¹¹

Opposing Viewpoints

In the past century, the practice of veiling has been controversial, both in the Middle East and in Europe, as the veil is seen as a symbol of oppression and fundamentalism or as freedom and identity. Image of the veil as a symbol of oppression dates back to the 18th and 19th century when European travelers visited the Middle East for the first time. Visitors to the region assumed that veiled women were more oppressed, more passive, and more ignorant than unveiled women, which contributed to exaggerated statements about the “imprisoned existence” of women in “the Orient” as compared to the “total freedom” enjoyed by women in Europe. Smolenski notes that one French traveler in the Levant called the veil “miserable”, and that the women in Damascus “hide their treasures” from Europeans.¹⁶ Of course, women were oppressed in both societies to a greater or lesser extent, when one takes into account women’s inability to vote and the physical constriction of the corset.¹⁷

Even today, the veil is perceived as a sign of restriction, particularly after the events of September 11, 2001. Katherine Bullock says that for European, and particularly American media, the Islamic veil is a symbol of “oppression, and as a shorthand for all the horrors of Islam: fundamentalism, terrorism, violence, and ‘backwardness.”¹⁸ Noted scholar Leila Ahmed emphasizes that although the veil is perceived as an oppressive custom, the women who wear the veil do not see it as such; it is, she says, “more than anything perhaps it is a symbol of women being separated from the world of men, and this is conventionally perceived in the West as oppression.”¹⁹ Amira Jarmakani, in her examination of images of Arab women in the United States, cites an advertisement for the clothing company the United Colors of Benetton, where on the left a girl is shown in a full-covering burqa, and on the right, a girl with hers pulled up to reveal her face as a representation of a woman who is “now free to find work in Kabul,” equating lifting the veil with liberation.²⁰

Muslim women choose to wear the veil for many reasons, one being that of a symbol of socio-economic status, as did the Prophet’s wives in the 7th century. The association of veiling with status can be dated back to pre-Islamic societies, such as the Greeks, Romans, Jews, and Assyrians.²¹ Smolenski says that even in the early days of Islam, primarily settled and/or urban people practiced both veiling and the seclusion of women, indicating that the women had enough wealth and status to abandon physical work, such as tending to crops, and could have servants leave the house to run errands for them.²² French anthropologist Germaine Tillion in her book, The Republic of Cousins, noted that peasant women who moved to larger towns and cities would begin wearing the veil as a symbol of upward mobility, that they had improved their socio-economic status.²³

Some scholars say that by wearing the veil, women can, effectively, be “invisible” while out in public, sometimes considered to be “male space.” Moroccan feminist Fatema Mernissi claims that the veil is “an expression of the invisibility of women on the street, a male space par excellence,” and that it means that she “has no right to be in the street,” because “only prostitutes and insane women wandered freely in the streets.”²⁴ Bullock, in her study of attitudes towards wearing the veil, found that women who wear hijab said that it made going out in public easier, helped them gain respect, aided in finding employment, and reduced harassment by men.²⁵ Van Nieuwkirk found that in Egypt, women explained that they took the veil as a “device to protect themselves against men as well as a device to protect men against women,” because they felt that “women should be protected against harassment by men and should not be exposed to male desire.” She says that either way, the “female body is perceived as sexual and lust-enticing.”²⁶

Some women have chosen to veil as a form of political protest against Westernization and, as noted by Bullock, “Western neo-imperialism.” Donnalee Dox says that dating back to the earliest resistance to British and French occupation in the Middle East, wearing the veil demonstrated opposition to colonial rule, whereas not veiling indicated a “complicity with Western values.”²⁷ Bullock says that by covering their heads, these Muslim women can show that they are “not happy with the current political situation, either with the policies pursued by the State and/or with the commercial, technological, political, and social invasion of their countries by the West,” particularly after the defeat of the Arab powers by Israel in the 1967 Six-Day War. She adds that others veil to “reject current behavior by young people and contemporary society.”²⁸

Many women wear the veil and other Islamic dress items such as loose-fitting, long-sleeved, ankle-length robes as a physical representation of their identity as Muslims. Sherifa Zuhur found that both those who wear the hijab and niqab and those who do not perceive doing so as a sign of religious affiliation.²⁹ Leila Ahmed says that wearing Islamic dress signals the wearer’s “adherence to an Islamic moral and sexual code,” allowing them to form friendships with men without suspicion of illicit or immoral activity.³⁰ Bullock found that many women who live outside of Muslim-majority nations—including second-generation immigrants to Western countries such as Canada, Great Britain, and France—do so as a “statement of personal identity as a Muslim woman.”³¹

The Veil in Islam

Some Muslim women wear a different variety of head and body coverings known as hijab,¹² from the headscarf which covers the hair and shoulders; niqāb, which covers the head, body, and has only a small opening for the eyes (worn by many women in the Arabian gulf); chador, an open cloak worn by many Iranian women and female teenagers (the Iranian government requires that women wear it at all times in public spaces); and burqa, which shrouds the entire body, with a mesh opening through which to see (as worn by women in Afghanistan). The term hijab, however, can refer to any face, head, or body covering worn by women after they reach puberty, specifically in the presence of adult males. Most often, Muslim women wear it as a symbol of modesty, privacy, and morality; however, in some countries, women are legally required to cover themselves to varying degrees. In contrast, some Muslim majority countries such as Turkey, Tunisia, and Tajikistan (and countries with significant Muslim minorities, such as France), have banned women from wearing the veil in some settings such as government jobs. In addition to being a religious act, wearing hijab is sometimes a political one, whether it is a legal obligation or worn by choice.

The Qur’an does not use the term hijab; in Sura (chapter) 24:30-31, it instructs both men and women to “restrain their sexual passions”, and that women should “wear their head-coverings over their bosoms,” and that they should not “display their adornment” except to members of their immediate family. The wearing of the hijab can be traced back to the Ḥadῑth (a collection of the Prophet Muḥammad’s sayings and actions) in the 7th century; it says that Allah (God) will not accept a woman’s prayer unless she is wearing a headcovering. Fatema Mernissi says that Islamic teachings denounce body ornamentation,¹³ especially for women, and it required “pious women to be modest in their appearance.”¹⁴ Natalie Smolenski notes that the Prophet’s wives were told to veil themselves, and to talk to men only through a curtain, probably as a “as a mark of their exalted status in the community of believers,” but also because they could “afford the luxury of veiling and decided to adopt a tradition followed by the prosperous settled people with whom the Muslims came into contact.”¹⁵

The content from this post is excerpted from The Salimpour School of Belly Dance Compendium. Volume 1: Beyond Jamila’s Articles. published by Suhaila International in 2015. This Compendium is an introduction to several topics raised in Jamila’s Article Book.

If you would like to make a citation for this article, we suggest the following format: Keyes, A. (2023). The Veil. Salimpour School. Retrieved insert retrieval date, from https://suhaila.com/the-veil/

1 Elizabeth Artemis Mourat, “The Veil and Oriental Dance,” accessed december 23, 2013, http://web.archive.org/web/20080311235151/http://www.shira.net/veilhistory.htm.

2 Malek Alloula’s The Colonial Harem, Vol. 21. (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1986) provides an insightful analysis of European photographs of Algerian women.

3 Laurel Victoria Gray, “The Mystique of the Veil,” Arabesque 9:4 (1983): 9.

4 Mourat, “The Veil.”

5 Ibid., and Dinicu, You Asked Aunt Rocky, 75.

6 Gray, “The Mystique of the Veil,” 17.

7 Gray, referenced in Mourat, “The Veil.”

8 Giselle Fobbs, “Classic American Creative Styles in Motion,” Habibi 3 (Summer 1993), accessed 11 November, 2013, http://thebestofhabibi.com/no-3-summer-1993/classic-american/.

9 Mourat, “The Veil.”

10 Dox, “Dancing Around Orientalism,” 61-2.

11 Deagon, “The Dance of the Seven Veils,” 244, 246.

12 The word hijab literally means “curtain” in Arabic, and also refers to the use of such as a means to segregate men and women.

13 Islamic teachings generally disapprove of the wearing of gold jewelry by men, as doing so is not considered modest.

14 Mernissi, Beyond the Veil, 161.

15 Natalie Smolenski, “Modes of Self-Representation among Female Arab Singers and Dancers,” McGill Journal of Middle East Studies 9 (2007): 53-4.

14 S.A.R. le Comte de Paris, Damas et le Liban: Extraits Du Journal d’un Voyage en Syrie au Printemps de 1860 (London: W. Jeffs, 1861), 9, accessed December 30, 2014, https://openlibrary.org/books/OL23488660M/Damas_et_le_Liban_extraits_du_journal_d’un_voyage_en_Syrie_au_printemps_de_1860.

17 Mabro, Veiled Half-Truths, 3.

18 Katherine Bullock, “Challenging Media Representations of the Veil: Contemporary Muslim Women’s Re-Veiling Movement,” American Journal of Islamic Social Sciences 17:3 (2000), 42.

19 Ahmed, “Western Ethnocentrism,” 523.

20 Jarmakani, Imagining Arab Womanhood, 161.

21 Leila Ahmed, Women and Gender in Islam: Historical Roots of a Modern Debate (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992), 55.

22 Smolenski, “Modes of Self-Representation,” 53.

23 Mernissi, Beyond the Veil, 191, n. 14. Germaine Tillion, The Republic of Cousins (Al Saqi Books, London) 1983.

24 Ibid., 97, 143.

25 Bullock, “Challenging Media Representations of the Veil,” 30-31.

26 Van Nieuwkerk, ‘A Trade Like Any Other’, 152.

27 Dox, “Dancing Around Orientalism,” 62.

28 Bullock, “Challenging Media Representations of the Veil,” 24-26.

29 Ibid., 28.

30 Ahmed, Women and Gender in Islam, 224.

31 Bullock, “Challenging Media Representations of the Veil,” 35.