Any news of Middle Eastern music and dance activity was sent through the Middle Eastern “grapevine.” Every Sunday a radio station from Fresno broadcasted a news and music program that opened with a familiar peshrof, which we all hummed. Once a week on KFAC [a Los Angeles-based classical music radio station that broadcasted from 1943 to 1989], Mr. Yegeshay Harout would present one half hour of both folk and classical music from Armenia and the Middle East. He embellished the program with quotes from poet Omar Khayyam.¹

From the radio, we learned months in advance of the future appearance of Rosemarie, an Oriental dancer from Egypt who sang in six languages. She was to be accompanied by Hanna Brothers orchestra at the Wilshire Ebell Theater.² I was 24, and she was the first dancer I saw in person. I can’t remember much about her dance, but she did not play finger cymbals.

Later, I met Rosemarie at the home of Zetrac, a friend of Anoosh’s. I was introduced to her as an aspiring Oriental dancer, and at her request I danced for her. I became shy and reluctant to dance in her presence, so she took my hands ring-around-the-rosy style, kindly coaxing me to imitate her movements. She was gentle in her criticisms of my “routine” and made suggestions about my arms, attitude, and steps.

One thing I remember her showing me was a hip figure eight going slowly all the way to the floor and all the way up again. We lost track of her whereabouts except for a brief sight of her at a newly opened club on Sunset Boulevard called 1001 Nights where she sang; I don’t believe she danced the night we visited. In fact, I never saw her dance again.

There was gossip about Rosemarie’s supposed loose morals. One lothario insisted he was invited to visit her in her hotel room, and she greeted him at the door wearing nothing but an untied dressing gown. I can say from personal experience he was a misogynist, and we all considered the source.

He got his comeuppance in the most unusual and diabolical way from a woman from which he had borrowed a large sum of money, promised to marry, and left Chicago to open a jewelry store in Los Angeles. She came to Los Angeles to claim him, but he eluded her.³

There had been other Oriental programs given from time to time. One of the most memorable was that by Shah Barovian, a Persian-Armenian tar player who performed at the Wilshire Ebell Theater around 1950 or so. I can still hear his beautiful rendition of “Naz Bar.” It seemed the entire audience sang along.

Richard Hagopian, a young ‘ud virtuoso from Fresno, was being compared to the great Udi Hrant. It would be a few years yet until I would dance to his music in a nightclub in Fresno. Hagopian was featured in what I believe was the first Middle Eastern nightclub in Hollywood, located near Sunset Boulevard.

Sometimes the audience there would get up and folk dance, but the club owners did not want a belly dancer as they considered it degrading. The club went out of business soon after it opened.

The Town and Country Market on La Cienega below Melrose had a Middle Eastern restaurant that featured music and folk dancing on weekends but no belly dancers. We went there a few times and joined in a debke weaving in and out of the tables. There were programs in which a great dancer, Khanza Omar, would perform feats. It was said that she was a Moroccan princess and occasionally worked as an extra in movies. She would perform a marvelous backbend, pick up a chair in her teeth, straighten to standing, and continue dancing while holding the chair between her teeth.

In later years I saw a documentary on Egyptian dancers, filmed in a tent near the pyramids. One of the dancers, dressed in assuit4 from head to toe and playing enormous finger cymbals, descended to the floor in double shimmies, leaned forward still keeping time to the music with her cymbals, picked up a table with her teeth, and balanced it high in the air while she danced.

I was never to see the beloved Khanza Omar. To everyone’s surprise, she died the weekend before the Arab community was to present her in a show called ExtravaKhanza.

Larry Potter’s supper club on Ventura Boulevard put an ad in Key magazine announcing the appearance of Atash (Nejla Ateş), a Turkish dancer and contortionist. I wasn’t too happy about her photographs in which she wore pasties and see-through pantaloons. Before I could get to see her she was whisked off to New York to be the featured dancer in Fanny⁵ a new Broadway musical. Around the same time, Samia Gamal came to Los Angeles without her musicians and performed a few times at a club on Sunset. She had a small part in a movie dancing at a bazaar way in the background.⁶

More clubs sprouted in Hollywood across the street from the Farmers’ Market such as the 1001 Nights on Sunset and Vine and Hershaway’s. Both were not open for long.

Then in the late 1950s, in addition to the Greek Village, Shaker’s Oasis opened in Hollywood. Most of the dancers there came from Turkey by way of Boston and Chicago. I was told that many of them were brought to the United States by Mohammed El-Bakkar, a well-known Lebanese singer and ‘ud player who produced several Middle Eastern albums; he also sang in the Broadway musical Fanny. I don’t remember anything distinctive about the dancers, but I do remember that they would often be lewd and aggressive. They did a version of lap dancing that brought the vice squad to check out the club more than once. Supposedly, the club was sued for allowing the customers to grope the dancers while tipping.

Up until that time I had only seen Egyptian dancers, and none I had seen performed floorwork or veil work. By contrast, most of the Turkish dancers I worked with performed suggestive taqsim and floorwork. They balanced customers’ drinks on their heads, rolled quarters on their stomachs, danced to the karşilama rhythm, and executed what I subsequently named the Turkish Drop (that is, in one count, a dancer dropping flat on her back on the floor from a spin, knees folded under). These clubs eventually went out of business, and I did not see another Turkish-style dancer until I danced in San Francisco.

From Boston came tales of two clubs where business was booming: Khaim Club and Club Zara. The press there reported weekly on the ongoing feud between the Lebanese singer Morocco and the fiery Algerian dancer Bedeah, and fans were eager to learn about the latest catfight.

The first successful club to open in Los Angeles that had an Oriental flavor was the Greek Village on Hollywood Boulevard. I believe the owners were from the East Coast. The wife was a hostess and sang in Greek, Turkish, and some Arabic. Originally the Greek Village was divided into two parts; the back was closed off when business was new. As business increased, the partition was moved farther and farther back until the entire space was revealed.

At this time, Italian actresses—Sylvia Mangano, Anna Magnami, Gina Lollobrigida—dominated the American screen with well-endowed to overflowing padded bras which propped up the likes of Jayne Mansfield and Jane Russell. They all wore off-the-shoulder blouses, which were as far as nudity was allowed in those days. Baring the midriff was considered risqué and still a no-no.

When the Greek Village hired my musicians, the musicians asked the owners if I could join them. The answer was no; the owners didn’t want a dancer in a cut-down costume [a two-piece ensemble that revealed the dancer’s midriff].

The owners’ daughter was a Jane Russell look-alike who wore revealing, off-the-shoulder blouses. She played a conga drum, which she held just below her bust. In an age of innocence, this was a feature attraction and a topic of conversation among many of the predominantly male customers. It didn’t matter if she could actually play. The sight of her was worth the price of admission.

Word got out to Greek sailors about the Greek Village; when their ships came to port, we were treated to some of the finest Greek dancing I’d ever seen. A bare light bulb hung directly over the stage, and it became a weekly contest to see which dancer could kick high enough to hit the light bulb. The favorite exhibition dance was the zeibekiko. The ouzo flowed freely as the man spread out his arms like an eagle’s wings in the ritual dance. Now and then a woman would dance a demure çiftetelli.

And so, I went to the Greek Village as a customer, occasionally getting up to dance at the insistence of my musicians, but receiving still no offer of employment. Business, however, was beginning to boom.

Eventually, professional musicians imported directly from Greece replaced my musicians. The first group included the scandalous Betty Daskalakis: singer, temptress, and designer of dresses slit in all the wrong places. She generated the kind of indignant gossip among “moral” people that aroused the curiosity of what seemed to be the whole of Los Angeles.

Just as the dancers on the Midway at the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893 offended the sensibility of what was considered acceptable, customers came in droves to view Betty first-hand to more effectively pass judgment. The Greek Village cash register rang from the profits of the protestors who stayed most of the night to watch Betty and make sure they saw what the gossip was all about. She never disappointed them. It wasn’t until the club was sold in the late 1950s that I finally had the chance to dance there.

When I was about 26, I decided to learn to play the ‘ud; I found a used one in the Arabic newspaper for $40. Going about finding a teacher was another story, and again I had to thank Anoosh for finding Mr. Gregor Levonian who was willing to teach me.

I really wanted to learn to play in the Egyptian style, but Levonian played in the Turkish style. But it was either him or nothing. I remember him complaining about a dancer who wanted him to compose music for her. It upset him that she wanted him to put harmony in his composition; he would say, “Our music is innocent—she should leave it alone!”⁷

From what I could gather about her dancing, she was an interpretive Armenian folk dancer, but she had an eye condition that made her legally blind. I heard her specialty was a whirling dervish dance. One time she miscalculated the dimensions of the stage at the Wilshire Ebell Theater, and, while performing her whirling dervish dance, she fell into the orchestra pit.

At this time, Anoosh prepared to remarry, and Jamila needed to find a new place to live. Now finished with his schooling, Bob Gary was preparing to leave for Mexico to work on a film. Jamila was still hopeful that Bob Gary would propose marriage or at least ask her to wait for him. Although he told her he would only be gone for a few months, he left with no assurances of the longevity of their relationship. Bob was focused on his career and did not seem interested in settling down any time soon.

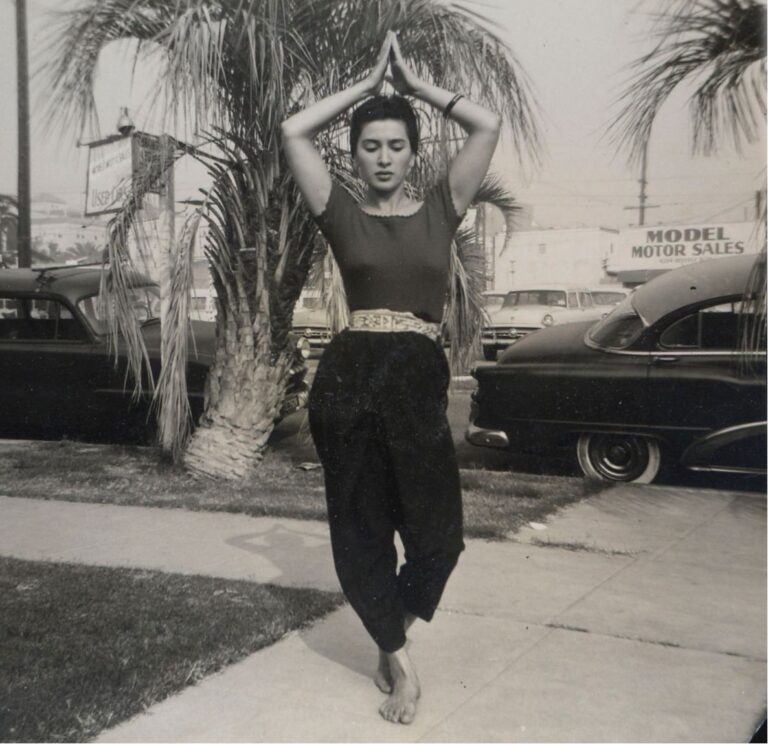

Just around the corner from Anoosh’s home, Jamila found a room to rent. The first person Jamila met in her new building was her landlady, Devi Dja, a professional Indonesian dancer, well known for her Balinese and Javanese dance.⁸

Also living in the building was Satyavrat (Satya) Jaswansingh Kshatriya, a professional Indian dancer of the classic Kathakali style; Satya studied cinema at the University of Southern California. Another tenant in the building, Claresa Degian, became Jamila’s first dance student.

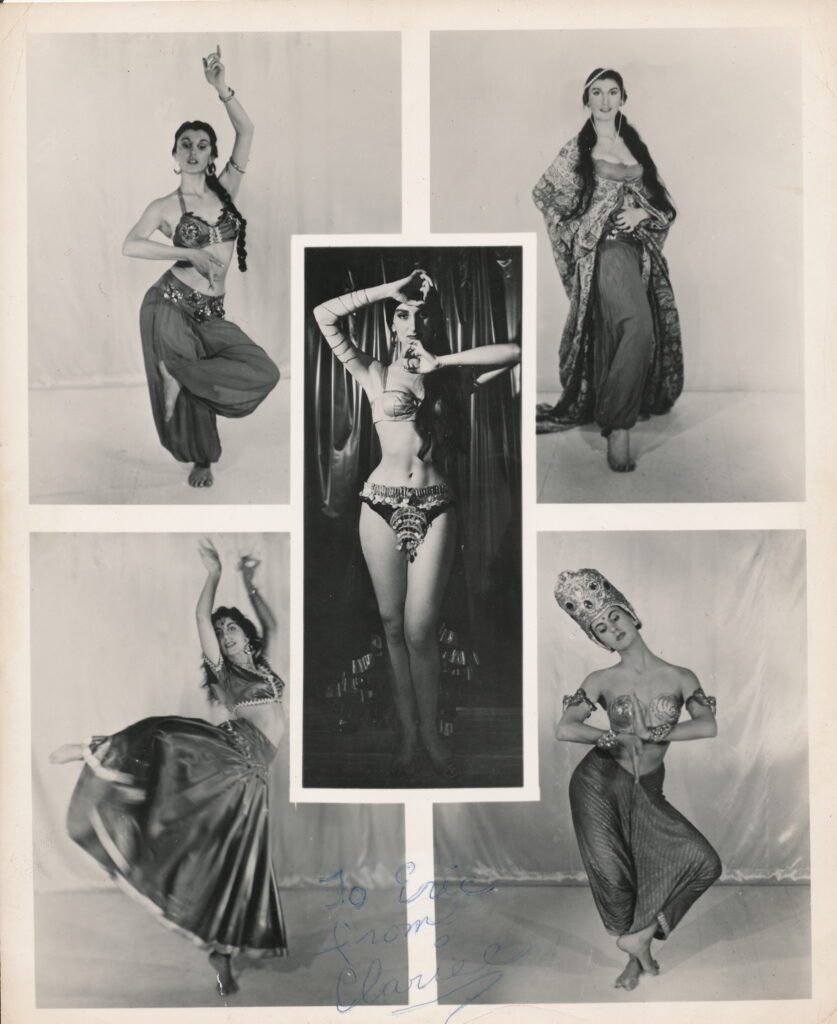

In my new rooming house, our landlady used the living room as a dance studio to teach, and Claresa hung a poster advertising her own performance of Indian, Spanish, Indonesian, and Turkish dancing. While I was curious about the Turkish dancing, I had reservations about the authenticity of it all because, although there were four pictures which were supposed to represent four different cultures, the costumes were shifted around in a make-do fashion and were not individually ethnically correct.

When we were introduced, she wanted to see me dance immediately. As I put on my finger cymbals, she exclaimed, “What are those?” I inferred that she had no Oriental dance training and had done no major research, either. I agreed to teach Claresa and another dancer in the house whenever I had free time; I was still taking community college classes to earn my high school diploma.

I first taught Oriental dance to old 78 rpm records, as record stores rarely carried Middle Eastern recordings. Not having a dance vocabulary yet, I repeated the music as I improvised the dance. My students watched and imitated me, asking questions that often I couldn’t answer. I would just perform the dance again and again until they got it.

Often, I would do variations on the theme, overlaying the basic movements, which only confused the students more, because I couldn’t break down the movements. Since I had never been taught the dance, I didn’t know how to teach it. There were no teachers, schools, or teaching methods.

From time to time, Claresa talked about her background. She was born in America but raised with Armenian social values; she felt caught between two cultures. Initially, her family tolerated her interest in dance. When they learned she intended to dance professionally, they openly disapproved. They admonished her to work at something decent—anything but the dance.

It was hard for her to agree to their demands. What did the world hold for her? To be marriageable she had to fit a certain mold: chaste, domestic, industrious, and obedient. She also felt insecure because of chicken pox scars on her face. She rebelled and sought acceptance in performance and theater where, from a distance, she was accepted and appreciated.

The content from this post is excerpted from The Salimpour School of Belly Dance Compendium. Volume 1: Beyond Jamila’s Articles. published by Suhaila International in 2015. This Compendium is an introduction to several topics raised in Jamila’s Article Book.

If you would like to make a citation for this article, we suggest the following format: Totten, V. (2023). Salimpour Story. Jamila\’s Hollywood Recollections. Salimpour School. Retrieved insert retrieval date, from https://suhailasalimpour.com/the-salimpour-story-jamilas-hollywood-recollections

¹ Omar Khayyam was a philosopher, mathematician, astronomer, and poet who lived in the 11th and 10th centuries. His most famous work is known as The Rubaiyat.

² The 1,270-seat Broadway-style theater is part of The Ebell of Los Angeles, a complex built in the Italian Renaissance style for the Los Angeles Women’s Club in 1927. The Ebell is still owned and operated by the LA Women’s Club.

³ “Memories of My Dismal Debut (Los Angeles, 1947),” Jamila’s Article Book, 2013, 12-14.

⁴ Sometimes called tulle bi-telle, assuit (pronounced: ass-ee-oot) is a mesh cotton fabric with an open weave with small bits of silver hammered into it to make patterns. Originally from the city of Assyut in Upper Egypt, assuit shawls became the signature fabric of Bal Anat. Antique assuit shawls were quite popular during the 1920s and 1930s after the discovery of Pharaoh Tutankhamen’s tomb in Egypt, and today are highly prized by collectors. Some shawls with heavy metalwork can sell for over $1,000.

⁵ Fanny, music and lyrics by Harold Rome (Broadway, 1954), based on a book by S. N. Behrman and Joshua Logan.

⁶ Valley of the Kings, directed by Robert Pirosh (Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1954)

⁷ Traditional Middle Eastern music is monophonic, meaning that it does not feature harmony, counterpoint, or polyphony.

⁸ Devi Dja (1914-1989) was called “the Pavlova of the Orient” for her Balinese and Javanese dance. Anna Pavlova (1881-1931) was a Russian ballerina famous for her performance of “The Dying Swan,” as choreographed by Michel Fokine, and for being the first ballerina to tour around the world.