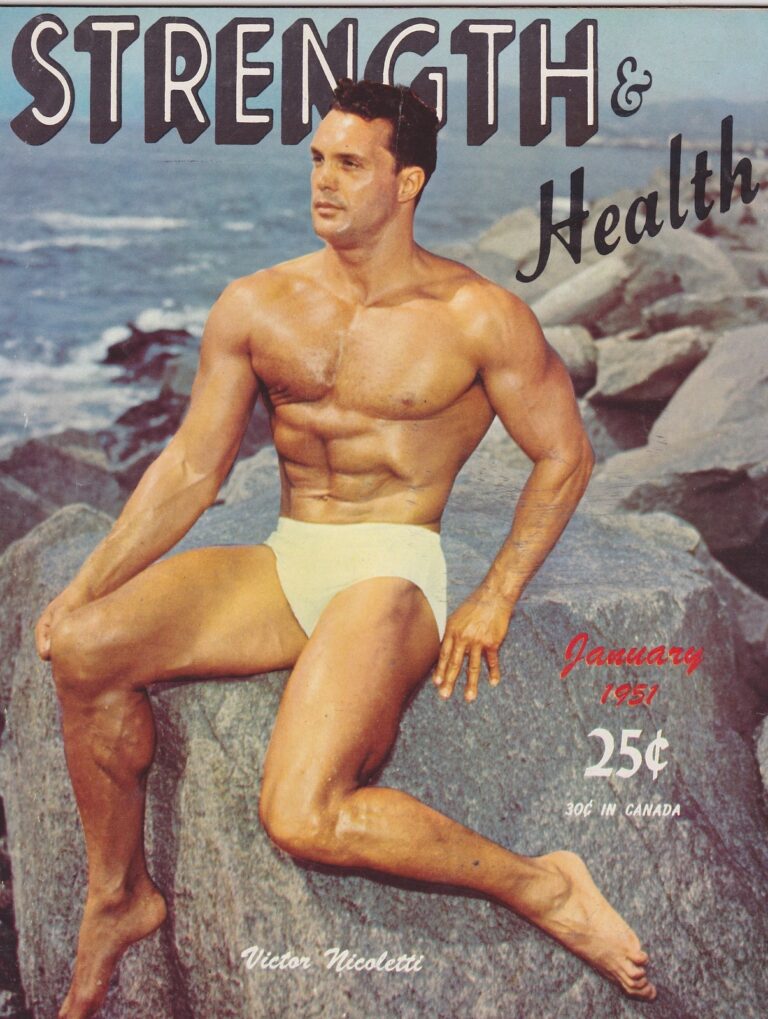

While Jamila was home on her break from the circus, she began dating Corporal Victorio Nicoletti, a long-time acquaintance who had served in the army as physical training instructor. While still in the service, Corporal Nicoletti won the Mr. New York City bodybuilding title at the Brooklyn YMCA in 1946.¹

The couple married soon after Jamila turned 19, and Jamila did not return to the circus. Victor wanted to continue his bodybuilding career, so the newlyweds moved to Los Angeles where most serious bodybuilders and competitors lived at that time.

The couple purchased a bungalow on Normandie Avenue in Hollywood with the help of the GI Bill (Serviceman’s Readjustment Act of 1944)², which helped American veterans of World War II find jobs, buy homes, and earn college degrees.³ They made several friends, including Bob Gary who regularly came to the house for training advice from Victor; Bob was studying to be a script supervisor.⁴ Jamila’s brother, Giuseppi, had also completed his service with the military, and he moved his wife and children to Los Angeles to be closer to his sister. Giuseppi had a regular job but also taught part-time at a flight school; he died in a plane crash when he was only 23.

When Giuseppi died, Jamila’s father came to visit her. At the time, the United States Federal Government was interviewing Jamila’s oldest brother, Vincenzo, a physicist, for a high-security job.

Jamila’s father met Victor’s friend, Bob Gary, and Bob was very outspoken about his support of the Communist Party. Jamila remembers her father telling Gary to stop being so vocal about his political views, because after World War II, certain ethnic groups, labor unions, and entertainers were targeted as being potential Communists or Communist sympathizers. Widespread concern existed that subversive groups (real and imagined) would collaboratively promote communism to overthrow the existing political system. Jamila’s father was worried Gary’s political leanings would be attributed to his own family, thereby making it difficult for Vincenzo to get the position working with the US Federal Government.

At this time, Jamila worked at Renoir of Hollywood, a jewelry design company where she learned about fashioning and crafting jewelry.⁵ She also befriended a co-worker, a young woman named Anahit Takorian.⁶

Jamila and Victor differed in what they wanted from their marriage. They divorced amicably and sold their home. From her part of the divorce settlement, Jamila was able to purchase a home on De Longpre Avenue in Hollywood.

Soon after, Jamila began dating Bob Gary. She wanted to work as a telephone exchange (switchboard) operator, which was considered a very respectable and well-paid position. The phone company would not hire Jamila because of her strong New York City accent. Bob helped Jamila with her diction and encouraged her to finish her high school education.

Jamila hoped that Bob would ask her to marry him, but he was still a student. As time passed, Jamila realized he was not likely to ask her, although he made himself more and more at home at her house. She realized that he was slowly starting to move into her home without the intention of marrying her. She sold her home and told Bob she no longer wanted to date him exclusively.

Jamila now needed a place to stay, and her friend Anahit had a very good lead on an apartment. Anahit’s mother, Hyganoosh (whom Jamila refers to as “Anoosh”), sought another renter in their home.

The year was 1946. I heard from a coworker of a room and board within walking distance from my job. The apartment was upstairs in a hacienda-style complex with several other units surrounding a large fountain. I rang the doorbell, and Hyganoosh greeted me in a friendly manner and invited me into her apartment. I felt comfortable with her; she reminded me of my family.

Six people lived in a small one bedroom second-floor apartment. One roomer slept on a day bed in the dining room. Her sons slept in the living room, on a Murphy bed and couch. Of the two beds in the bedroom, Anoosh slept in one and her daughter in the other. I wondered where I would sleep. Anoosh explained to me that the male roomer was going to leave; she would take his day bed in the dining room, and I would take her bed.

I moved in and was given a dresser drawer and a place for my clothes in the closet. Anoosh cooked breakfast, made lunch for us to take to work, and prepared homemade dinners waiting when we came home. Her eldest son told me that I disturbed him when I used the bathroom during the night and asked if I would “Please put toilet paper in the bowl before to muffle the sound.” Talk about the Princess and the Pea⁷—he was it! But Anoosh was my friend, and her friendship was worth his pickiness.

Anoosh’s household didn’t mingle with Americans. They worked among Americans, but when they came home their first language was Armenian (they were Armenians from Egypt), the second was Turkish (when they didn’t want children to know what they were saying), and the third was Arabic (when they spoke with friends from Egypt). Arabic music filled the house; Mohammed Abdel Wahab, Umm Kulthum, and the like were played over and over again on worn out 78 rpm records.

Jamila and Anoosh became very good friends. Anoosh loved to people watch, and she invited Jamila to the weekly farmers’ market to eat roasted barbeque meat on a hamburger bun and observe the shoppers and merchants.

The farmers’ market reminded Anoosh of her youth in Alexandria, Egypt, with its many outdoor cafes where you could sip coffee and watch people. A hamburger was exotic food for her since she only cooked Egyptian meals at home.

Anoosh and Jamila frequented the La Tosca Theater in Hollywood to see the once-a-month special showing of Egyptian movies, typically musicals. The theater routinely showed two different movies a day, with one repeated twice the same day. Anoosh and Jamila stayed for both, and the two would attend all showings. The theater sold Middle Eastern food in the lobby along with music on 78 rpm records. The available music featured songs from the movies along with current favorites from Egypt that included the emerging Egyptian singer, Umm Kulthum. It was here that Jamila bought much of her music at the start of her belly dance career.

When we got home we would play the records and imitate the dancers we had seen in the films. Other than watching the dancers in Egyptian movies once a month, the only other woman I saw dancing was my landlady, who danced in the house to her 78 rpm records, and I joined in. When she danced, she would bring her left hand up over her face, palms outward as if she was covering her face with a shawl. Whenever she had a gathering of her female friends, each one would get up and dance; all assumed the same pose and mannerisms that were the basic “folk” movements of Arabic dance. The footwork was a shuffle forward with the right foot flat on the downbeat, left foot on the ball of the foot behind the right. There were a couple of variations such as changing from right to left, but in general the step was a basic shuffle.

When watching the dancers in Egyptian movies, I noticed that some of them played finger cymbals. After some time, I heard through the Armenian grapevine of a hardware store in the neighborhood that had finger cymbals for sale, and I rushed over and bought them. Of course, I didn’t know how to play them, and Hyganoosh was of no help. She put them on and just clanked them. Although she was enthusiastic, her rhythms made no sense. I struggled for a 4/4 beat with a left-right-right-left-right.

While living with Mrs. Takorian, Jamila began attending Los Angeles Community College to complete her high school education with financial help from her father. She met several students and began dating again⁸ including, for a short while, a young Persian student. When she inquired if he thought their relationship would become more serious, his answer was a vehement “no.” He wanted to marry a virgin Persian girl from his own village.

Jamila also went out with a handsome young man who was quite wealthy. Jamila enjoyed his company and was thrilled when he proposed to her soon after they started dating exclusively. When she spoke to him about how he felt about children, he told her that would not be possible. The marriage would be in name only; he was gay and he would only marry her to keep up appearances. Jamila, however, wanted a full relationship, so she turned down his proposal. She returned to Bob Gary, and the two dated again.

Meanwhile, the diverse, yet close-knit, Middle Eastern community in Los Angeles accepted Jamila as one of their own; families welcomed her into their homes, and she was privy to the local gossip.

Although she was accepted, she was still Sicilian, which afforded her freedoms not available to a woman of Middle Eastern descent. A “good” Middle Eastern girl would not dance in public, so the community matriarchs actually encouraged Jamila’s interest in learning belly dance. They also understood that her real interest in the dance was the art: the graceful and percussive movements interpreting the beautiful music.

In 1947, I became a professional Oriental dancer; I was 21. Anoosh made me a costume, and I was available to dance whenever the occasion arose.

At that time, there were no Middle Eastern clubs in Los Angeles in which to perform. My first paying dance jobs were performing at women’s gatherings, birthday parties, baby showers, and festive occasions—but for women only. Once a year I danced at the Turkish New Year party and a gathering of Americans of Middle Eastern descent at Los Feliz Park. I also performed for the Armenian Home [a senior citizen’s residency], the Armenian Great Benevolent Union, private parties, and the like.

There were also no real professional musicians in town. Musical ensembles gathered together because music was their hobby, not their profession. And so it was that my musicians consisted of the Hanna Brothers orchestra: auto mechanics by day and musicians whenever an occasion called for them to play. If they needed an extra musician on ‘ud, qanun, or darbouka, they knew an amateur who wanted to sit in and play. They weren’t Abdel Wahab, but they had soul.

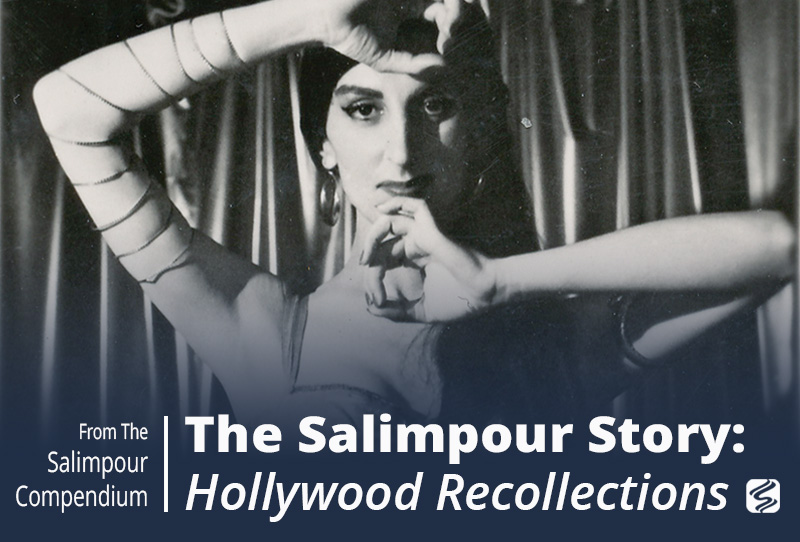

The content from this post is excerpted from The Salimpour School of Belly Dance Compendium. Volume 1: Beyond Jamila’s Articles. published by Suhaila International in 2015. This Compendium is an introduction to several topics raised in Jamila’s Article Book.

If you would like to make a citation for this article, we suggest the following format: Totten, V. (2023). Salimpour Story. Jamila Moves to California. Salimpour School. Retrieved insert retrieval date, from https://salimpourschool.com/the-salimpour-story-jamila-moves-to-california

¹ “Mr. New York: Former Champ Crowns Soldier as Adonis,” Long Island Star Journal, February 12, 1946, 16.

² Servicemen’s Readjustment Act (1944), accessed March 7, 2014, http://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?flash=true&doc=76.

³ When Jamila’s father returned to New York City after his visit, he soon moved back to Sicily. Although they corresponded regularly, Jamila never saw him again

⁴ Bob Gary (1920-2010) ultimately had a prolific career as a script supervisor, working on many shows including The Waltons, ER, Dynasty, Star Trek, Star Trek TNG, and many more.

⁵ Renoir of Hollywood, started by Jerry Fels in 1946, was renamed Renoir of California in 1948, and the company closed in 1964. Renoir jewelry is highly collectible in the vintage jewelry market.

⁶ Anahit is also the name of the Armenian goddess of war, but her role evolved in the 5th century BCE to be the main Armenian female deity, goddess of wisdom, fertility, and healing.

⁷ Fairy tale written by Hans Christian Andersen and published in 1835.

⁸ In the late 1940s and through the 1950s, single men and women often dated several people at once unless a couple decided to become exclusive. Such dates happened at restaurants, ice cream parlors, movie theaters, and other public places. As Jamila was very attractive and outgoing, she was asked her out frequently.