(Hollywood, USA, 1950)

Habibi: Vol. 2, No. 4 (1975)

The word got around that an oriental restaurant was opening on Hollywood Boulevard. For me, the good part was they were going to hire the musicians that accompanied me when I danced (because I knew musicians through the gatherings with Hyganoosh). I was hoping that after those musicians started working they would be asked if they knew any dancers, then my musicians would say that I was their feature dancer, then I would be asked to audition, and then of course I would be hired immediately. Well, I waited, and waited, and waited for news of an opening of some kind…but nothing! I decided to check out what this Greek club was all about; Hyganoosh and I put on our Sunday best and went to the Greek Village.

The Greek Village was located on Hollywood Boulevard between Vine and Highland Avenue. It had a conventional storefront with doors in the middle and display windows on either side containing dining tables. Passers-by gawked at the people eating in the windows, and, between mouthfuls, the people in the windows gawked at the people walking on Hollywood Boulevard. The musicians were in direct view from the windows; the original intention of the owners was for the street traffic to be fascinated by the goings-on inside and, hopefully, to patronize the club; but people on the street pressed against the windows for a better view made it difficult for customers in the windows to enjoy their meal. The restaurant was mostly a family affair. The husband cooked, tended bar, and lead the Greek line dances. His wife participated in the Greek folk dances where women were included, and she danced a very sedate ciftetelli in her own dress (not a costume). Her dance was casual, repetitious, and folksy; she had at the most three steps, no veil, no floor work, no taqsim, no finger cymbals. The star of the show was their daughter, a tall and gorgeous brunette who looked like Sophia Loren. She played a large conga drum to Greek, Turkish, or Arabic music, whichever style happened to be playing at the time. I didn’t think she was especially knowledgeable or gifted on the conga, but her presence and beauty made up for her lack of talent or authenticity.

Many customers were eager to do solo folk dances. I saw some of the finest zeibekiko dancers. The zeibekiko is of Turkish origin and is a man’s dance in which he imitates a male eagle by crouching and extending his arms like wings, hopping around in strong movements, and at times jumping sideways with both feet in the air. ¹

I was given no hope to be hired as a dancer at the Greek Village. They did not have an oriental dancer, and they thought that “Mamma’s” ciftetelli was enough. I was not even asked to dance in my street clothes, and no importance was given to the fact that I used to dance with the musicians they had hired. They were expected to play all night without stopping, that is except for an occasional cigarette (while they continued playing) and, of course, the necessary visits to the bathroom. There were no unions or conditions for them, and their main security was their dayjobs. Since Tommy was Greek, born in Turkey, he was highly valued because he could sing and play in both languages. The other musicians played in Arabic and Armenian and so together they would round out an evening of oriental music. Nothing in it for me, though! More of the waiting period.

Hyganoosh told me that she heard of a man who played the oud (a pear-shaped ancestor to the European lute) and would be willing to teach me. I found an oud for sale in the Arabic newspaper and drove to Glendale to purchase it for the sum of 40 US dollars, which was a lot of money in those days.

My oud teacher, Gregor, had the first Armenian orchestra in Fresno featured on Fresno radio. His first instrument was the nay (an Arabic flute), but because he developed an asthma-related problem, he took up playing the oud as his second instrument. He built an oud variation with a longer neck to span more octaves. Gregor was an oudist in the Turkish style. Step by step, I was to learn a peshrof, a musical exercise which is a musical composition with variations in tempo. The training was by ear, and the lessons were repetitive. Gradually you build a repertoire and develop a background recognition of the various scales or maqamat (the Arabic and Turkish modal equivalent to scales). Gregor would improvise on a maqam, and I would think it was hopeless for me. Would I ever be able to absorb enough of the music to compose spontaneously as Gregor did?

People would seek him out; one of the thorns in his side was an Armenian woman who would borrow his compositions on record for her troupe and put harmony to his music. Gregor would comment, “Oriental music is innocent. There has never been harmony to it. . . She should leave it alone!”

I practiced and struggled and came to appreciate more than ever the improvisational ability of the Middle Eastern musician. I heard at that time of the musical genius of a boy from Fresno by the name of Richard Hagopian. He appeared for a brief time at the Peacock restaurant on Western and Sunset. We intended to go see him, but before we made arrangements he returned to Fresno. They called him the young Udi Hrant, an Armenian oud player who helped popularize Turkish classical music in the 1930s and 1940s. All the Armenians knew of Richard Hagopian. I looked forward to the day when I could hear him play. (I never dreamed that I would someday dance to his music. There were many wonderful things in store.) Richard Hagopian would become a legend in his time, respected by his friends and honored by his fellow musicians.

Between disappointments, I continued investigating the music and history of the Middle East. I watched Arabic movies every month, hopeful that they would feature dancers. I would attend any function that was an excuse to eat oriental food. Every week there was a benefit for something or other.

The culture was being kept intact. I loved being in the middle of it. Hyganoosh informed me that she put the word out in the Armenian grapevine to find a husband. I had to look for another place to live as her new husband would be coming back to the house with her. I found a place right around the corner and, behold, also my very first student.

This article was published in Jamila’s Article Book: Selections of Jamila Salimpour’s Articles Published in Habibi Magazine, 1974-1988, published by Suhaila International in 2013. This Article Book excerpt is an edited version of what originally appeared in Habibi: Vol. 2, No. 4 (1975).

¹ I recently saw a documentary from Turkey in which the rebetiko changed to include women during the twentieth century, and a Turkish dance group has made it into a line dance. The rhythm was there, but the posture was no longer that of the male eagle; there were no more high leaps and no solos. In the clubs now, you can see women performing the rebetiko.

Photo Credits:

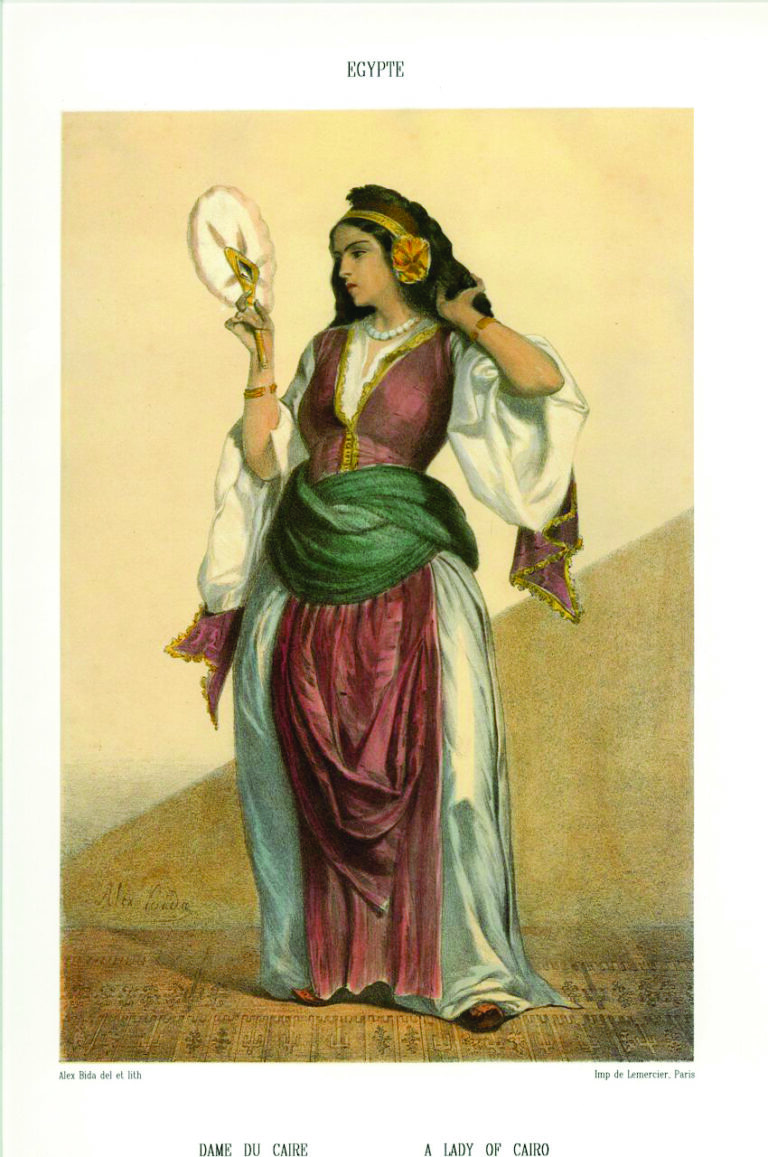

- Lady of Cairo, Egypt, Barbot, Prosper, artist, 1851, Public Domain, https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47d9-6827-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

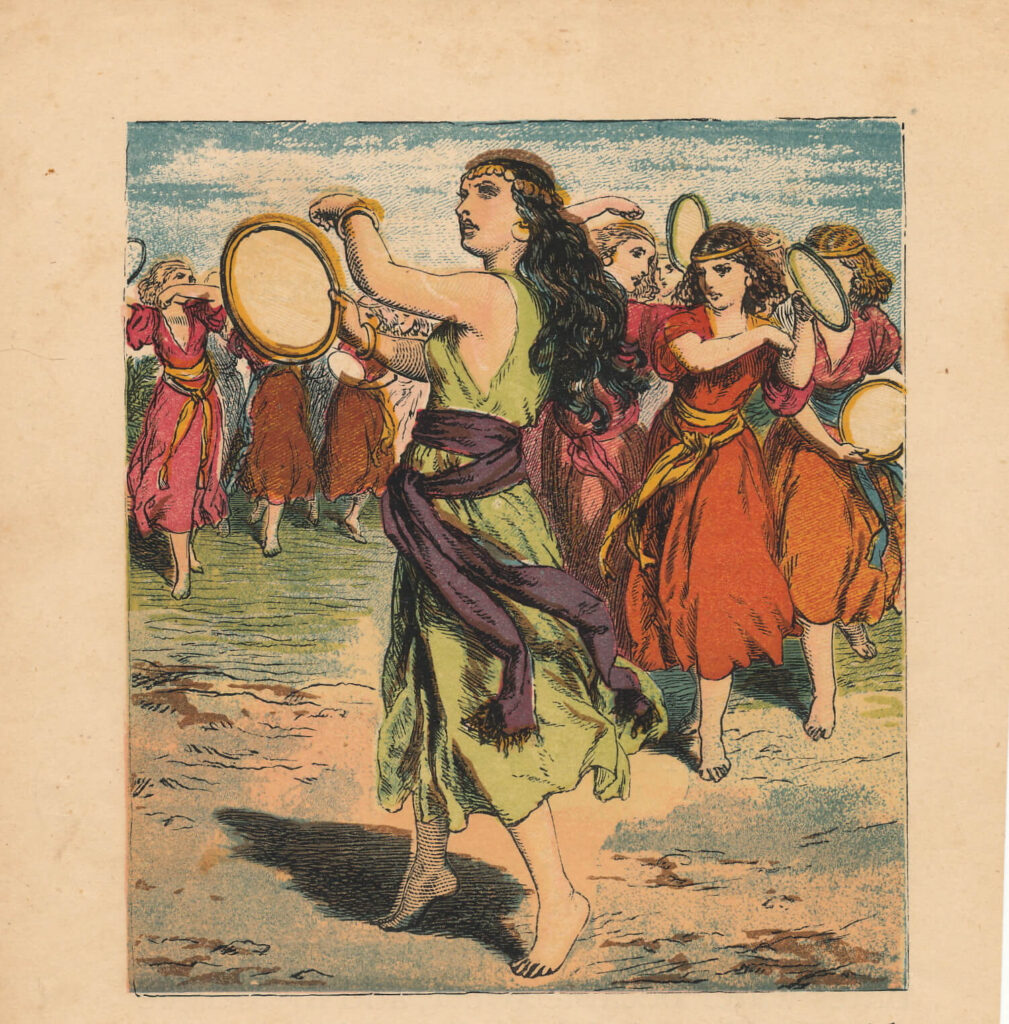

- Tambourine Girls, Public Domain.

- Musicians, Public Domain.