(or Verbalizing Middle Eastern Dance)

Habibi: Vol. 3, No. 7 (1976)

Egyptian films were shown once a month at the La Tosca Theater in Los Angeles. There was usually a double feature, one film heavy on drama and the other with music, comedy, singing, and dancing. Hopefully, if there was a dance sequence, it would feature one of the well-known stars. Tahia Carioca was the favorite after World War II, with Samia Gamal running a close second.

My first lesson in Middle Eastern dance happened when, after watching several dance sequences, I controlled my awe of Tahia Carioca and objectively concentrated on watching her footwork, instead of her projection and facial expressions. I became aware that what she was doing was accomplished by training and wasn’t just an “ethnic emotional experience”. I would watch film after film, waiting for the scene in the movie that gave her the opportunity to dance. Tahia Carioca’s movements were fluid with pelvic combinations that defied analysis. Her delivery was so natural it made the dance look easy. I began to recognize repetition and patterns. When the music was fast she executed certain steps embellished with her own body ability specialties, and when the music was slow her interpretation evolved within another pattern. I recently found out that Tahia’s teacher was Badia Masabni, owner and director of the famous Casino Opera in Cairo, which also produced the inspiration for future dancers including Nadia Gamal.

I always stayed through the two double features and felt fortunate if I could visually break down anything she did. My eyes were glued to the movie screen. She had such control! It was at the same time inspiring and discouraging. Whether she would like to take the credit or not, I consider Tahia Carioca my first teacher aided by Hyganoosh Takorian. When we came home from the movie Hyaganoosh would put on her “ciftetelli”, and we would both “become” Tahia… (we hoped!).

It was this visual trial and error learning experience that was the start for many an oriental dancing hopeful. In this day of hundreds of schools, it may be hard to imagine a time when information was simply not available. Also, there was no interest or curiosity for Americans until ten years or so after World War II.

In my investigations of belly dance, I have never come across anyone with valid credentials or credibility who had names for steps or patterns such as those used in ballet. If there is to be a lasting understanding and appreciation of oriental dance as an art form, I think a standard vocabulary must develop that would adequately describe steps, transitions, variations, combinations, and interpretations. Information must be made available for those who want to investigate folk customs and ethnological evolution of styles and steps. If the level of performance is going to be raised, the why’s and how-to’s must be answered. Just as ballet studios may specify for instance the Cecchetti method of ballet instruction, so must the danse du ventre specify any one style that adheres to the more traditional style.

The next question is “what is traditional”? Webster’s dictionary says, it is the oral delivery of information, opinions, doctrines, practices, rites, and customs, from father to son, or from ancestors to posterity; the transmission of any knowledge, opinions, or practices, from forefathers to descendants by oral communication, without written memorials.

In addition to the movies, Arab festivals, and get-togethers, I tried to see any and every show that called itself Middle Eastern. I never saw any Egyptian dancers do what we now call “floor work” until Helena Kallianiotes came from Zara, the famous club in Boston. It was a shock for myself and my dance friends who saw it as degrading; since we didn’t see it performed in Egyptian films, [we did not consider it] an acceptable traditional form. We approached Helena and, after complimenting her dance, asked her why she got on the floor and undulated. She was patient and humored us and answered something to the effect that as far as she knew it had always been done; but we tried to persuade her not to do floor work anymore. Lucky for her she didn’t listen to us, and her beautiful dance was left intact. Later, Helena gave me a special booklet published by Dance Perspectives in which newspaperman William Curtis (in Egypt at the same time Gustav Flaubert had his fling with the famous Ghawazee dancer, Kutchuk Hanem) unknowingly aided posterity and tradition by his lengthy description of Hanem’s dance. I thought that because “floor work” was not done in Egyptian movies or by the Egyptian professionals that came to Los Angeles, it was therefore not traditional or acceptable; I was proven wrong when I read in detail what Kutchuk Hanem executed (what I later dubbed “Turkish Drop”). It was most certainly traditional though barred in certain areas for whatever social, political, or religious reasons; it survived in other areas and was brought to the West Coast by Tabora Najim. Her “Turkish Drop” and the description of the floor work technique of Kutchuk were identical, and even though they still do not want dancers to descend to the floor in Los Angeles, I consider it traditional and, therefore, include it in my teaching.

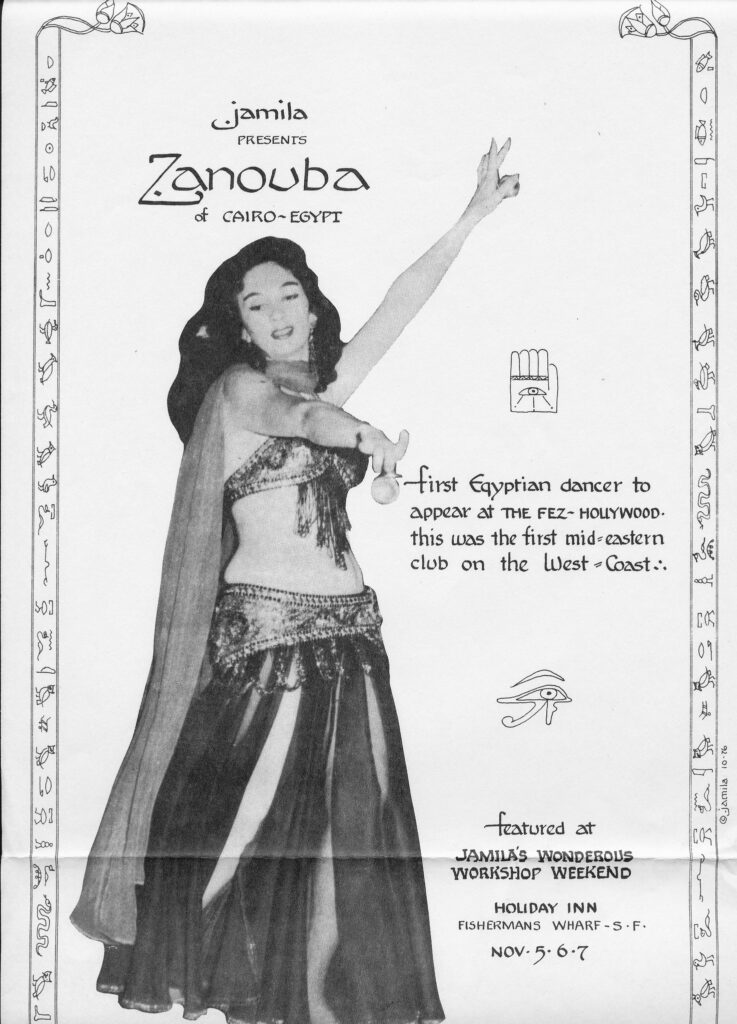

Los Angeles was first influenced by Zenouba, the first Egyptian dancer to come to The Fez which was the first Egyptian club to open in Los Angeles and indeed on the West Coast. Maya Medwar and Siham were next, followed by a bevy of nameless dancing girls, some influenced by Maya, others by Zenouba and Siham. None of these ladies did floor or veil work, and only Zenouba played finger cymbals. Since most of the dancers came from Egypt, my style developed along with theirs. Also, it was in keeping with the monthly movies, which were mainly from Egypt and danced in the same style as the dancers from Los Angeles. If I saw a movie that one of my dancer-hopeful friends had missed, I would try to describe to her the new thing I had seen such-and-such dancers do.

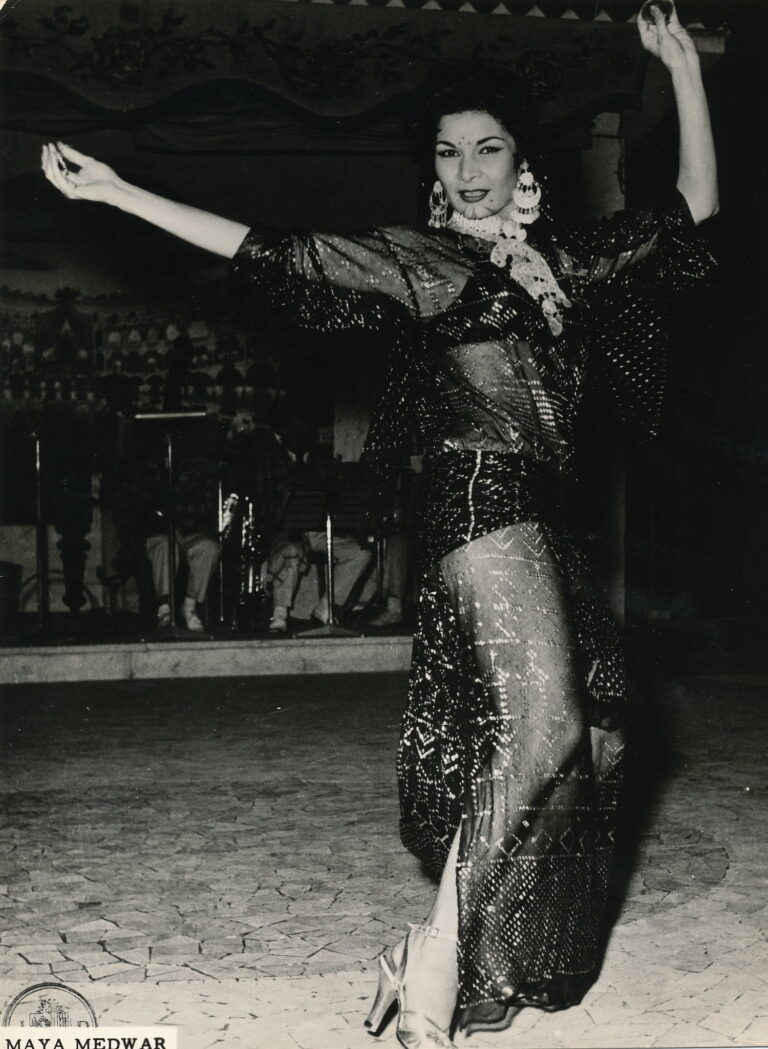

I remember seeing a movie once that featured a great dancer whose name escapes me. In the scene where she finally dances, she begins her routine on the balls of her feet in a steady, fast shuffling forward, which I described as a “Choo-Choo”. In trying to describe what I had seen, I had to remember and piece together her technique by physically recreating her body motions as I verbalized them. I remember concentrating on her feet, legs, and knees. Maya Medwar separated her specialties with a step I call “Basic Egyptian”. I called it that because all the Egyptians use it in their dance. From that step later evolved an Egyptian family of steps.

When I worked at the Bagdad Cabaret, a dancer came from back East and was hired to perform at the club. The musicians were grumbling but visibly impressed when she demanded an afternoon rehearsal before she would work in the club. The owner, Yousef Kouyoumdjian, was also impressed by her demands, and all the dancers came the following afternoon to see how and what she did that warranted a rehearsal. Tabora Najim was her name, and she was a professional in every sense of the word. She knew her music, breaks, and cues; when she stopped the musicians and made them repeat again and again the passages she wanted to emphasize, the end result was exciting. In describing her specialties I coined the phrase “Turkish Drop” that has now become common among dancers and teachers alike, which must be attributed to Tabora Najim. It was Tabora who I first saw descend to the floor in a one-split-second count, dropping from a fast spin with knees folded under, flat on her spine. Since her style was Turkish, I combined the style with the action and called it “Turkish Drop”. She was also the first dancer I ever saw do what I call “stomach flutter”. No Egyptian dancer did it that I had ever seen.

Maya Medwar had a vertical pelvic roll, which created an optical illusion. When I call out for that step all my students respond immediately when I simply say “Maya”. Zenouba had a couple of characteristics that I captured and now teach, and her name is part of my teaching vocabulary. Helena’s veil work is part of my veil routine with her name as part of the steps.

Distinctive names, which identify body mechanics such as Algerian, Turkish, Arabic, and Egyptian, can mentally separate style and movements and aid in simplifying the learning process. Whatever influences I have had, I feel it is only fair to give credit to those dancers with whom I had the good fortune to work. To the best of my ability I give them credit so that my students and my student’s students will remember some of the pioneers who paved the way for the oriental dance to become popular and to be accepted as an art form. I hope that some day all the teachers can meet and exchange ideas as to how to communicate better to their students by using a standard verbalization which would have the flavor and character of the Middle East. We can look forward to, perhaps, an accredited board such as they have in ballet which travels around visiting ballet schools and tests students after they have reached a certain level of achievement. Now is the time for suggestions and a sharing of teaching discoveries. There is still much to do, but I feel there has been progress and lots of intercultural exposure. I am pleased to know that I leave behind me several students who have the talent and capability to perform, teach, and preserve the ethnic character of the danse du ventre.

This article was published in Jamila’s Article Book: Selections of Jamila Salimpour’s Articles Published in Habibi Magazine, 1974-1988, published by Suhaila International in 2013. This Article Book excerpt is an edited version of what originally appeared in Habibi: Vol. 3, No. 7 (1976).

Photo Captions:

- Bal Anat dancer in Turkish drop position, c1975. From the Ghanima Gaditana personal photograph archives.

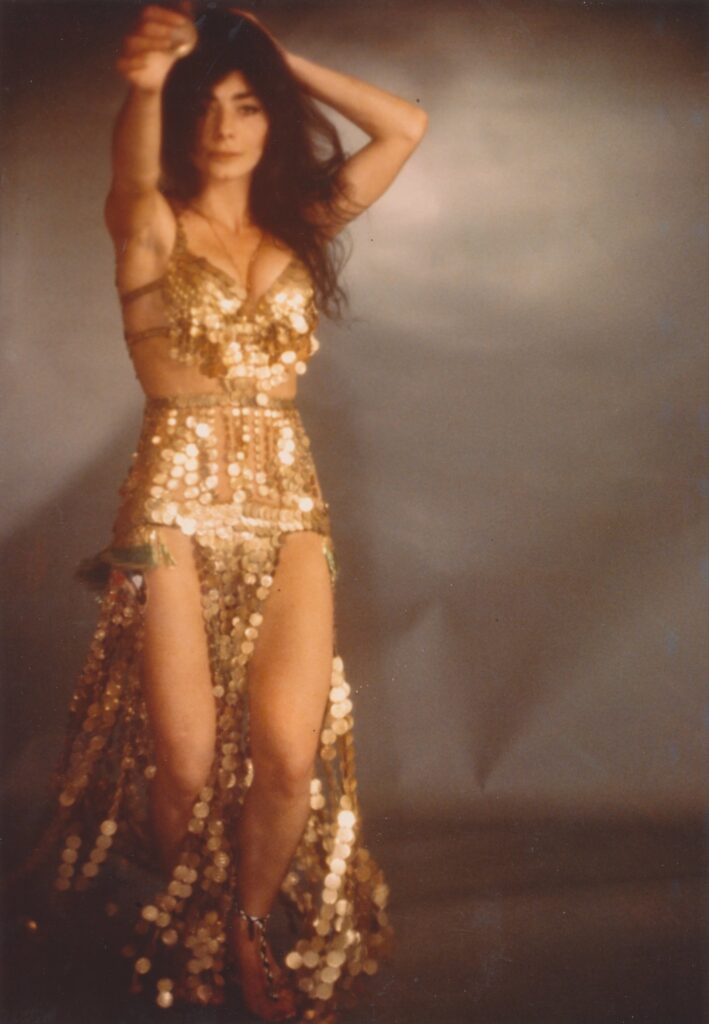

- Helena Kallianiotes in a gold disc costume. Promotional photo from the Jamila Salimpour personal archives.

- Maya Medwar in beaded costume. Promotional photo from the Jamila Salimpour personal archives.

- Maya Medwar in an assuit costume. Promotional photo from the Jamila Salimpour personal archives.

- Workshop flier for a Zenouba workshop sponsored by Jamila Salimpour. From the Jamilia Salimpour personal archives.