Habibi: Vol. 4, No. 1 (1977)

Then, without touching the carpet or the sherbet with her hands, she took the little glass between her lips, drank the liquid, and replaced the empty vessel upright on the carpet. It was done so daintily, so roguishly, with such spirit and dexterity, that we were all delighted.²

Muscle dancing, as specialty of the Ouled Naïl, was described to me by an Arab who viewed it with admiration. The isolation of muscles of the arms, pectorals, abdomen, hips and thighs were incorporated into a dance. I heard of a performer who could make a silver dollar flip over on her abdomen sometimes using two at a time on either side of her navel. I hear from a physician now practicing in Egypt, that a dancing girl can lie on her back, and with a full glass of water standing on one side of her abdomen and an empty glass on the other, can by contraction of the muscles on the side supporting the full glass, project the water from it, so as to fill the empty glass. This, of course, is not strictly dancing, but it is part of the technique which underlies classic dancing and it witnesses to the thoroughness with which the technical side of Egyptian dancing is still cultivated. All of this was done without vulgar or lewd intent and was appreciated as a physical feat and nothing more. Jeremiah Lynch saw:

The best dance of the evening, by the best dancer, lasted half an hour; yet she did not lift her feet from the carpet, nor did she move out of a space a yard wide. Amina fascinated us all by the langorous motions of her body, the serpentine grace of her movements, and her moist almond eyes, revealing that she was a marvel of passionate chastity and pride. After a while she gave us a new dance. A tiny glass of sherbet, flecked with pomegranate, was placed in the middle of the carpet. The Ghawazee keeping accord, in the sinuous motions of her lithe form, to the rhythm of the music, but never stirring her feet, gradually lowered her body until her lips approached the delicious draught.

There used to be a theatre on La Cienega Blvd. in Los Angeles owned and operated by Raymond Rohauer which showed 16mm films exclusively. By putting your name on his mailing list, you received a monthly program which listed films by specialty; each evening would feature one subject, and there were some evenings which featured only documentary dance films. I went quite often, enjoying the variety, and now as I look back I wonder where he got his material not to mention the dedication and patience it took to accumulate and catalog such a collection. The lobby of the small theater was more like a living room, tastefully decorated with art objects and paintings, some of which were for sale. Tea or coffee was always brewing for you to avail yourself whenever you wished. With fond memories of this setting I can recall some of the most spectacular documentary films I have ever seen. I will limit my descriptions here to the Middle Eastern dances I saw.

Most of the films were primitive attempts at filmmaking with sheets hastily tacked onto walls as a backdrop, but despite the lack of scenery at least they had a sound track. One film I saw opened with a woman in kneeling position. She was dressed in a Turko-Persian costume which consisted of an A-shaped coat, full pantaloons, and pill-box hat bordered with coins over which was draped a gauzey fabric which hung down her back. Her eyebrows had been painted together, the effect of which was quite startling. She remained in that kneeling position for the length of the dance.

Her only accompaniment was a drummer who accentuated her movements with a 6/8 rhythm on the zarb, the Persian wooden drum. Through mime, she danced the story of a seamstress who showed you the beautiful fabric on which she was working, invited you to feel it, continued to sew, thread needles, and again sew until the garment was completed. How deft she was! This was yet another example of a dance form that evolved from everyday work. She talked to you without words by communicating through facial expressions and body and hand movements. I was spellbound! This composition must have taken a long time to choreograph, and I was happy it had been preserved on film.

Many of the dances of people throughout the world are dance stories of working chores such as the water pot dance which uses the pot as a dance prop in imitation of the balance needed to walk great distances while balancing a water jug on your head. The movie Justine had a sequence inside the palace with fifteen or twenty girls dancing and balancing large earthenware jugs on their heads to the accompaniment of mizmars and large tabla baladi drums. ³

The challenge to balance things can still be seen in any Greek club when patrons from the audience will get up to dance, and in the course of an evening some one will put a whiskey glass or wine bottle on their head while dancing vigorously. A dancing girl from Libya is described as “Wild grace lashed in Silken scarves…Very graceful posturing is the chief feature of the scarf dance of Libyan dancing girls, women of prepossessing appearance. This girl adds variety to her performance by balancing a tray laden with tea things on her head while sinking to and rising from her knees. The dance is performed to a monotonous accompaniment of drumming and clapping of hands.”

While some of the comments may not be flattering we can also surmise that in most cases the writers did not live in the Middle East but merely visited without in any way absorbing the culture. With the current interest in dance history, we await more of the documentary of the musicologist and dance ethnologist.

This article was published in Jamila’s Article Book: Selections of Jamila Salimpour’s Articles Published in Habibi Magazine, 1974-1988, published by Suhaila International in 2013. This Article Book excerpt is an edited version of what originally appeared in Habibi: Vol. 4, No. 1 (1977).

¹ Article originally titled: “Gaudy Gimmicks of the Ghawazee (and Other Public Dancing Girl Tales).”

² Jeremiah Lynch, Egyptian Sketches (London: Edward Arnold, 1890).

³ Justine, directed by George Cukor (Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation, 1969).

Photo Credits:

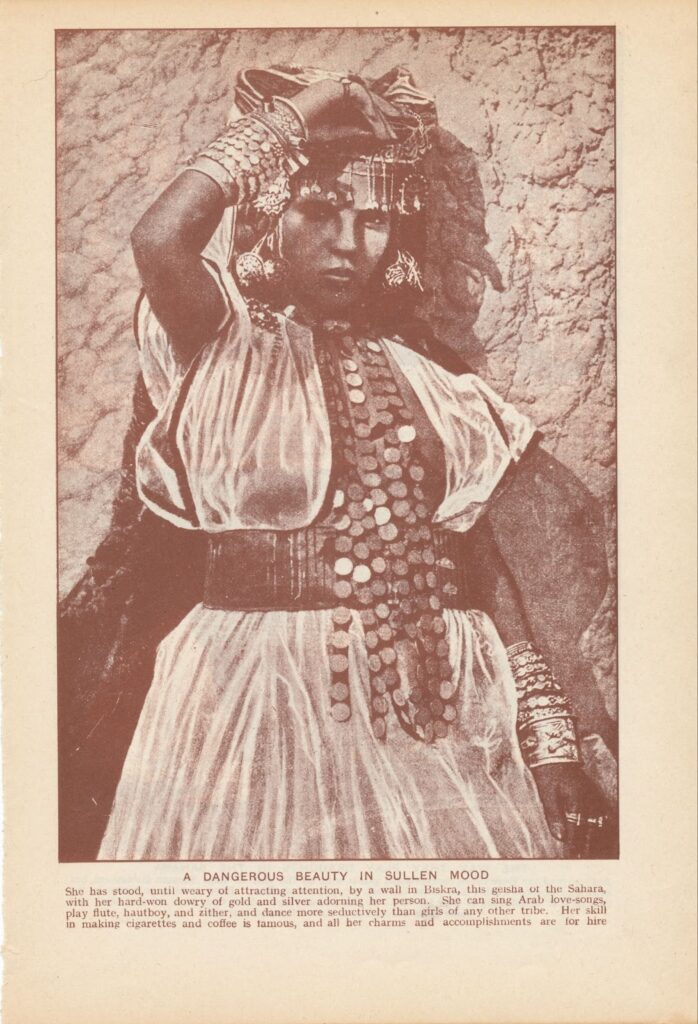

- A Dancer Of The Cafés, Algeria, Unknown author – 300 ppi scan of the National Geographic Magazine, Volume 31 (1917), page 269, Public Domain, https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/National_Geographic_Magazine/Volume_31/Number_3/Gypsies_and_Moors_in_Northern_Africa#/media/File:Dancer_of_the_Cafes_NGM-v31-p269.jpg

- A dancer in Biskra, Algeria, 1922, Peoples of All Nations, Their Life Today and the Story of Their Past, volume I: Abyssinia to the British Empire, edited by JA Hammerton and published by the Educational Book Company (London, 1922), Public Domain.

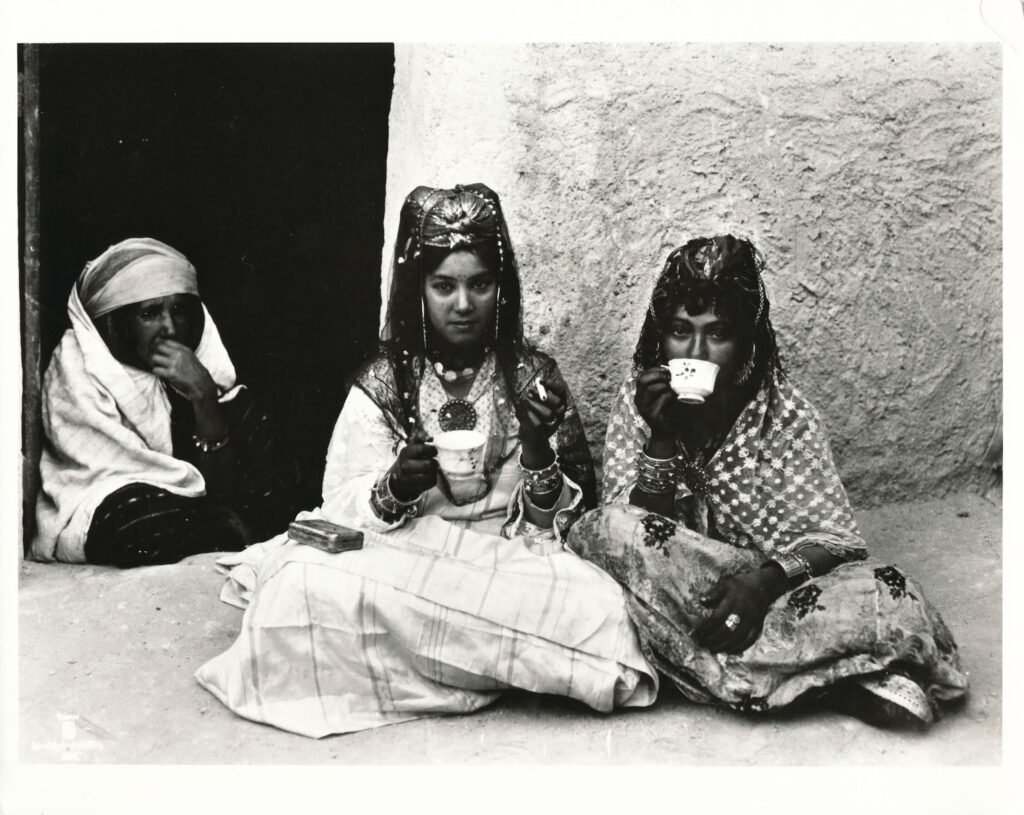

- Women of the Tribe Ouled Naïl, Photograph, Unknown Photographer, Public Domain.

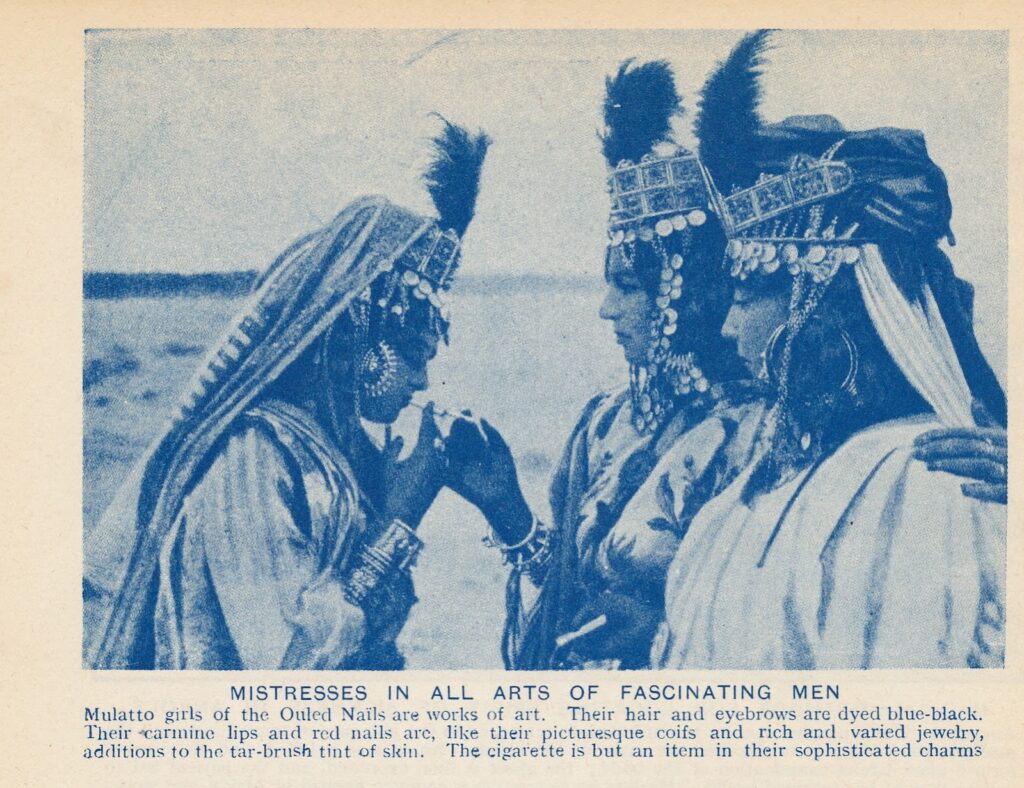

- Ouled Naïl women, The Secret Museum of Mankind, Volume II, 1935, CC BY-NC 3.0 US.

- Tunisian Tea Plate Dancer, 1908, Photograph, Unknown Photographer, Creative Commons, CC-BY-NC-SA 2.0.