The tale of Sheherezade is part of the collection of folktales from the Middle East and Western Asia compiled in between the 8th and 13th centuries known as the One Thousand and One Nights, sometimes called the Arabian Nights Entertainments, or by its Arabic name, Alf Layla Wa Layla. The main frame story concerns a Persian king who discovers that not only has his brother’s wife been unfaithful, but also his own new bride. The king has his wife executed and decides that all women are adultresses and not to be trusted. He then marries a succession of virgins every day only to execute each one the next morning. Eventually his vizier can not find any more virgins, and the vizier’s daughter, Sheherazade, offers to marry the king. The vizier reluctantly agrees. On the night of her marriage to the king, Sheherazade begins to tell him a story, but stops her story-telling at sunrise. The king, at first angry, agrees to wait until the next night to hear the rest of her tale, but she continues to leave her tales unfinished, night after night, for 1,001 nights. Some of the most famous tales include “Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp,” “Sinbad the Sailor,” and “Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves.”¹

The tales have been transformed as they have been told through the years, both in the Middle East and in Europe. They were first transmitted orally, then were combined and written for the first time in Iraq around the 10th century.² The stories were first introduced to Europe through the French translation by Antoine Galland in the early 18th century. The ten volume translation by Sir Richard Francis Burton, however, is perhaps the most famous, as it emphasized and exaggerated the tales’ sexual elements, scandalizing his Victorian readership. Burton’s liberal translation likely contributed to the Western perception of Arabs as being immoral and savage; indeed, scholar Rebecca Stone comments that Victorians considered the tales in their original form to be unfit “reading for women and for young people.”³ In 1899, J. C. Madrus’ created his own translation, published in serial volumes over the course of five years; this new translation, combined with Salomania and a surge of interest in all things Oriental, imparted Middle Eastern influences on fashion and decorative arts.⁴

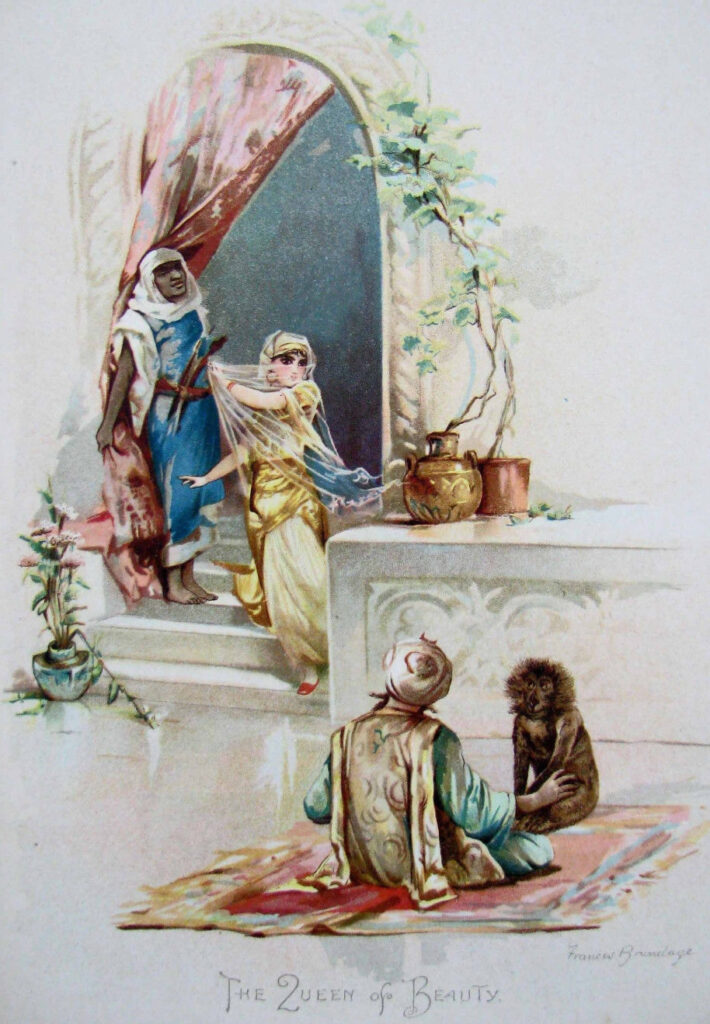

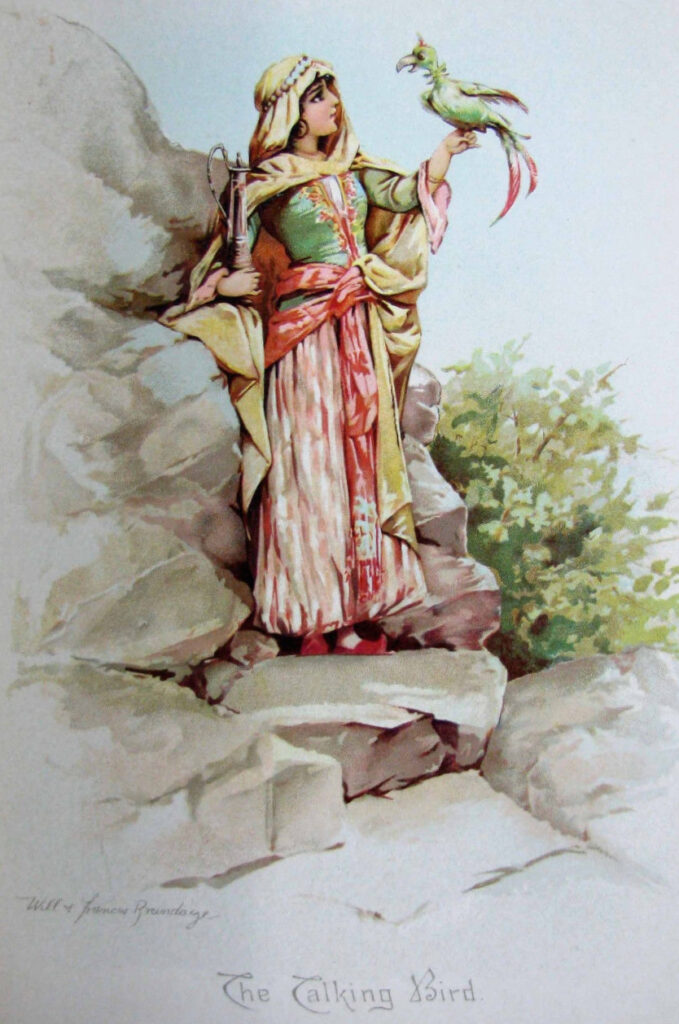

The tales have been immensely influential on the West’s perception of the Middle East and the people that live there. For many 19th-century European travelers to the Middle East, their only exposure to the region was through the stories of One Thousand and One Nights. The Nights, however, portray a timeless, fantasy “Orient,” just as Western fairy tales do of Europe. Scholar Judy Mabro notes that in her research for her anthology of writings from European travelers in the Middle East that the “image of the flamboyant, erotic and cruel Orient was applied indiscriminately to a large geographical area,” regardless of whether they were in Baghdad, Algiers, or Cairo (cities with quite different histories, dialects, architecture, and cultures).⁵ Davinia Caddy also says that as more people had access to various translations of the One Thousand and One Nights, its readership began to “perceive this imagined ‘Other’ land as a place of fantasy displaced from the body politic of the West—an arena of free, absolutist, erotic constructions.”⁶

This homogenous fantasy land has influenced the image of the Middle East in the Western consciousness, arts, and media, from images of sheikhs, harem girls, genies, camel caravans, and magic lamps. In addition to influencing Western stage arts—such as the “Oriental” dances of the Ballets Russes—scholar Stone rightly points out that the popularity of the tales of the One Thousand and One Nights in Hollywood, from films such as The Thief of Baghdad (1924), The 7th Voyage of Sinbad (1958), and Disney’s Aladdin (1992) have all reinforced these tropes.⁷ In recent years, newer translations of the original tales from Arabic to English have been more faithful to the source material, as that by Husain Haddawy, published in 2008.

The content from this post is excerpted from The Salimpour School of Belly Dance Compendium. Volume 1: Beyond Jamila’s Articles. published by Suhaila International in 2015. This Compendium is an introduction to several topics raised in Jamila’s Article Book.

If you would like to make a citation for this article, we suggest the following format: Keyes, A. (2023). One Thousand and One Arabian Nights. Salimpour School. Retrieved insert retrieval date, from https://salimpourschool.com/

1 Interestingly, these three were not a part of the original Arabic tales, but are almost certainly authentic folk tales from the region. French translator Antoine Galland added them to the compendium of tales later in his own volume.

2 Margaret Sironval, “The Image of Sheherazade in French and English Editions of the Thousand and One Nights (Eighteenth-Nineteenth centuries),” The Arabian Nights and Orientalism: Perspectives from East and West, ed. Yuriko Yamanaka and Tetsuo Nishio (London: I.B. Taurus, 2006), 219.

3 Rebecca Stone, “Reverse Imagery: Middle Eastern Themes in Hollywood,” in Images of Enchantment: Visual and Performing Arts of the Middle East, ed. Sherifa Zuhur (Cairo: American University in Cairo Press, 1998), 249

4 Davinia Caddy, “Variations on the Dance of the Seven Veils,” Cambridge Opera Journal, 17:1 (March 2005): 47.

5 Mabro, Veiled Half-Truths, 28.

6 Caddy, “Variations,” 47.

7 Stone, “Reverse Imagery,” 250.