Just as Jamila observed Middle Eastern dancers in the nightclubs of California, the dancers in New York were doing the same. Sabah Nissan who worked in the early days of the 8th Avenue clubs of New York City said that she would “go down to Philadelphia and dance with Armenians,” then go to a Turkish or Arabic hafla (Arabic for “Party”), and notice that the people would execute similar movements with different characterization and stylization. She said that at an Armenian gathering, one wouldn’t use her hips, but at an Arabic or Turkish party, one would.¹⁰ The sheer frequency of performance engagements helped many dancers learn, as many were dancing sets as long as 40 minutes three-to-six nights a week; some of the dancers from the Middle East even helped the Americans.¹¹

In California, too, Middle Eastern immigrant gatherings evolved into nightclubs. According to nightclub veteran dancer Aisha Ali, Middle Eastern entertainment became popular in Los Angeles during the late 1950s when a few of the patrons of Hershaway’s 1001 Nights, an Arabic coffee house, began performing Lebanese folk dances. Although Middle Eastern entertainment was not new to the city in the form of haflat and mahrajanat (Arabic for “festivals”) at church halls and community centers, Ali says that Hershaway’s was probably Los Angeles’ first Arabic nightclub.¹²

By 1959, the Fez Supper Club opened in Hollywood, professional dancers from the Middle East had begun coming to Los Angeles more frequently. When Hershaway’s closed, the Fez was the only Arabic cabaret in the Los Angeles area and did a thriving business. Many of their patrons were Americans who had just discovered Arabic music and dance.¹³ The Fez, owned by the Shelby family, featured dancer Zenouba (née Leila Elwi) and a musical group called the Oriental Trio, which included tabla player Mohammad El Miri, his wife Shiham who sang, and Khamis El Fino on cümbüş (a 20th-century Turkish banjo). Maya Medwar, originally from Syria, also performed at the Fez; before coming to the United States she had attended the High Institute for Acting in Cairo where she studied dance and drama. She also trained with Mahmoud Reda’s brother, Ali.

The Greek Village and the Torch Room opened at approximately the same time, catering to mostly Greek immigrants, and capitalizing on the fact that many Americans, according to Ali, knew little about Arabs, but felt that Greek culture was “an exotic diversion with which they felt comfortable.” The Greek Village, also featured Greek musicians, including a bouzouki, clarinet, accordion, singers, and tambourine.¹⁴ Aisha Ali notes that the practice of performing what we now call “floor work” evolved out of the need to do something exciting during the “plodding” çiftetelli. She, like Jamila, also comments on the blazing fast speed of the up-tempo songs.¹⁵

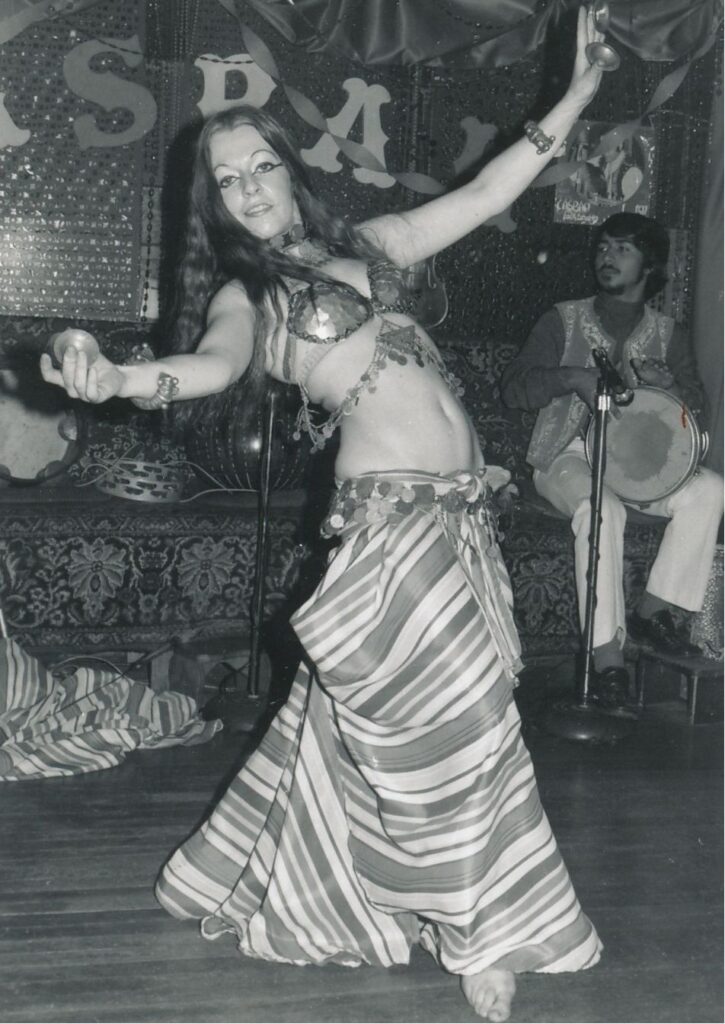

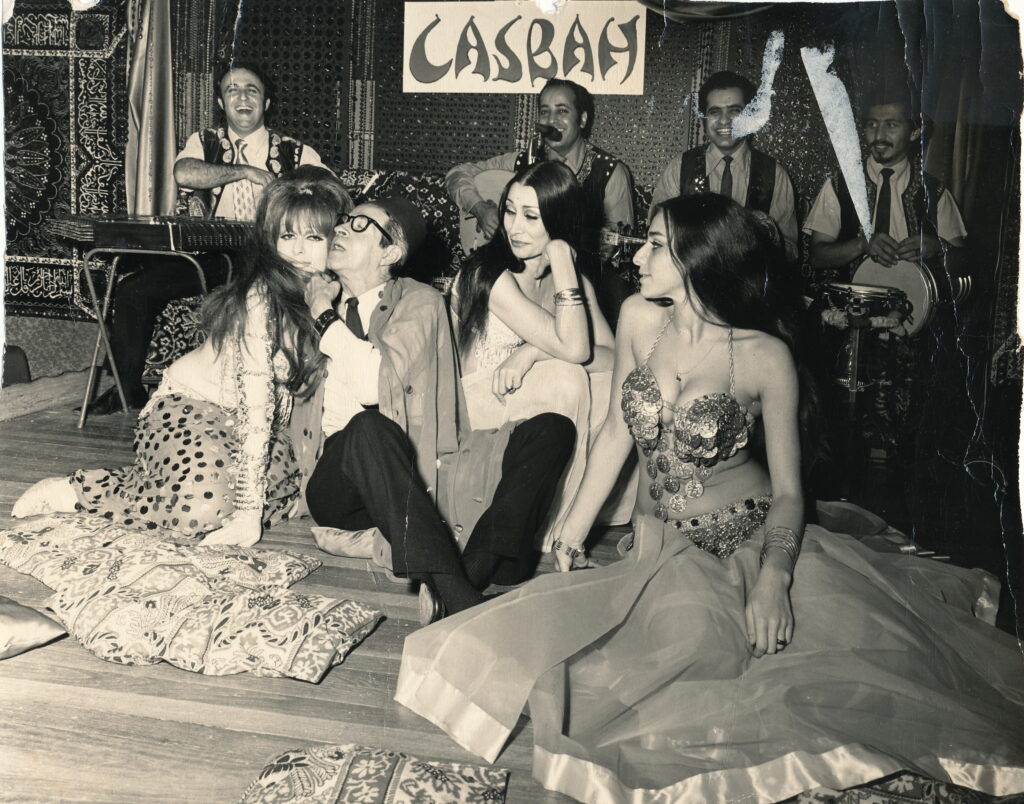

The Middle Eastern nightclub came to northern California in the 1960s. In Fresno, the Armenian immigrant community grew, and a restaurant known as the Baghdad (different from Jamila’s Bagdad Cabaret) featured entertainment on the weekends. According to Aisha Ali, by 1963, the demand in San Francisco for Oriental dancers had grown, and both 12 Adler Place and a nearby venue called Gigi’s had opened in North Beach. She notes that the sound of the music in San Francisco, in addition to being a mix of Middle Eastern musical styles, also incorporated Persian and even Hispanic musicians and instruments.¹⁶ By the mid-60s, the Jamila Salimpour and Yousef Kouyounjian had opened the Bagdad Cabaret on Broadway; the Casbah opened shortly afterward.¹⁷

The multi-part nightclub show developed during this time, consisting of a fast opener, a series of slow and mid-paced songs, and an upbeat finale. In the early 1960s, many of the musicians in the southern California nightclubs were Syrian, Palestinian, Lebanese, Greek, Armenian, and Turkish and played music from their respective homelands. Aisha Ali says that they had little previous experience playing for dancers, and would generally play a medley of popular songs in common time, with one or two taqāsīm as interludes. As many of the musicians were Armenian and Turkish, most nightclub ensembles finished with a fast karşilama (an Anatolian rhythm in 9/8 time).¹⁸ The musicians also blended their various musical traditions, techniques, and styles, creating a new style of Middle Eastern music.¹⁹ In an effort to appeal to American ears, many musicians adapted their indigenous songs, adding in Western instruments such as electric guitars, bass guitars, and organs, which became almost a requirement for some ensembles. Other groups added harmonization, which is not used in traditional Arabic music.²⁰ Others used Western equivalents of Middle Eastern instruments, such as an oboe in place of the mijwiz and mizmar, and a Western transverse flute instead of the nay. Others took advantage of the clarinet’s prominent place in Turkish and Armenian music, as it appealed to their non-Middle Eastern audiences.²¹ Some of the best well-known musicians of this era and style include Eddie “the Sheik” Kochak, Freddy Elias, Richard Hagopian, George Abdo, Mohammed El-Bakkar, and John Bilezikjian.

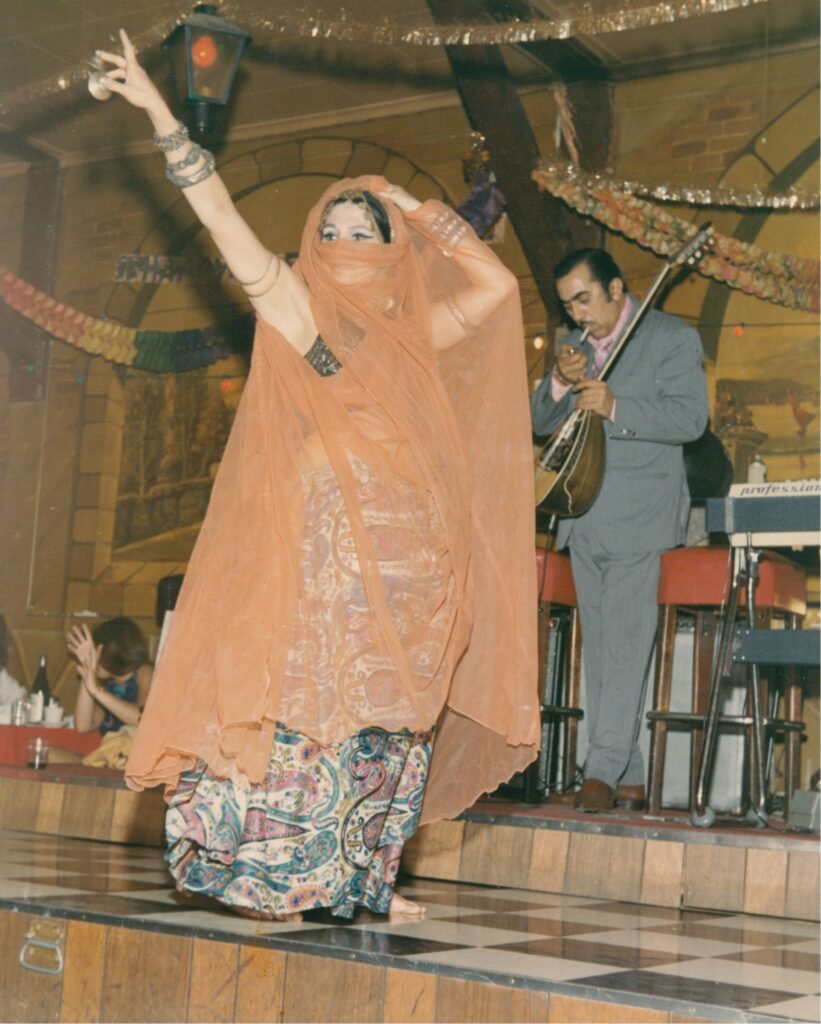

The era of the Middle Eastern nightclub in the United States stretched from the early 1950s to the early 1970s, when immigrants from the region opened restaurants for their own communities, and Americans interested in exotic food and entertainment joined them. Musicians and dancers from all around the Middle East exchanged musical and movement styles in these venues, creating a hybrid style that is now considered uniquely American. At the height of their popularity, dancers and musicians performed five to six nights a week working into the wee hours of the morning.

Following World War II, large groups of Arab Christians, Jews, and Muslims from the Levant, Egypt, and North Africa came to the United States to escape political turmoil in their home countries. They created communities in Detroit, New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, and San Francisco, as well as other major American cities.¹ Ann Rasmussen says that according to Arab-American musicians, patrons, and audiences, a Lebanese-American couple opened the first Middle Eastern nightclub in the United States, Club Zara (sometimes spelled Zahra), in Boston in 1952. A few years later, the same owners opened Club Morocco, named after the club’s co-owner, a professional singer and dancer from Lebanon. The clubs were patronized, notably, by an international clientele and cosmopolitan-minded Americans.²

Meanwhile, in New York, Greek and Armenian nightclubs were popping up on 8th Avenue as havens for immigrants seeking out a little piece of home. Some of the musicians were already accomplished professionals from the “old country,” while others were amateurs. Here, Western instruments, such as piano, were added to the ensembles. By the mid-1950s, there were, according to Harold G. Hagopian, dozens of clubs along 8th Avenue between 23rd and 42nd Streets. In the 1960s, according to Rasmussen, approximately twelve nightclubs were in operation in “Greek Town,” a neighborhood in New York City near 8th Avenue and 20th street.³ The best-known New York venues were Port Said (the first New York club, according to Adam Lahm⁴), Egyptian Gardens, Ali Baba, Seventh Veil, and the Grecian Palace Café. These clubs attracted chic New Yorkers and celebrities—including Bobby Kennedy, Aristotle Onassis, and Harry Belafonte⁵—as well as jazz musicians such as Dave Brubeck and Leonard Bernstein seeking to add a little Eastern influence to their compositions.⁶ The evolution from immigrant gathering place to belly dance venue in New York happened organically, as it did in California, according to Adam Lahm, with dancers first appearing in skirts and blouses then eventually using veils and wearing what we now recognize as the belly dance bra and belt.⁷

Veteran New York dancer and researcher Morocco says that in the early days of the nightclubs in New York, there was a whole generation of “walkers—anybody who would stand there in a costume got a job because there were far more jobs than dancers.” Lahm comments that American dancers “got their foot in the door” with their “good looks,” but their love of the music is what made them want to stay.⁸ As more people learned how to dance, and as the public was exposed to more dancers, she says, the level of the dance improved.⁹

Several factors contributed to the decline in popularity of the Middle Eastern nightclubs in the United States. One was the emerging strip club business, where customers seeking bare flesh could see more than what the belly dancers showed; by the mid-70s, the nightclubs in San Francisco were increasingly surrounded by strip joints such as the Condor Club. Another was the growing awareness of American audiences to the realities of the Middle East, as noted by Ann Rasmussen.²² Events such as the Black September attacks at the Munich Olympics in 1972, the civil war in Lebanon in the mid-1970s, and the growing spectre of Arab and Muslim terrorism all took hold in the popular American consciousness. It’s likely that the oil embargo by Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries beginning in 1973, combined with a concurrent stock market crash creating a persistent economic recession also contributed. Several musicians told Rasmussen that during the Persian Gulf War of 1990, activity in the nightclubs waned, as Arab communities went into a state of “social mourning” and American audiences felt more apprehension towards Middle Eastern culture.²³ In the late 1990s, a few clubs still operated in New York City, such as the Lafayette Grill and Le Figaro Cafe, but the last ones closed soon after the events of September 11, 2001. Some of the remaining clubs had been located in southern Manhattan near the attacks and suffered economically (many businesses of all kinds had to close temporarily); others fell out of popularity because of their association with the Middle East.

If you would like to make a citation for this article, we suggest the following format: Keyes, A. (2023). Male Belly Dancers in the United States. Salimpour School. Retrieved insert retrieval date, from https://www.suhaila.com/middle-eastern-nightclubs-in-the-united-states/

1 Shay and Sellers-Young, introduction, 12.

2 Rasmussen, “An Evening in the Orient,” 175.

3 Ibid., 176.

4 Adam Lahm, “Looking Back: The New York Middle Eastern Dance Scene,” Arabesque 9:4 (1983): 6-7.

5 Ibid., 6.

6 Harold G. Hagopian, liner notes to Armenians on 8th Avenue, Traditional Crossroads CD 4279, CD, 1996.

7 Lahm, “Looking Back,” 7.

8 Ibid.

9 Phyllis Saretta, “The Clubs: Charisma and Technique,” Arabesque 6:2 (1980): 5.

10 Ibid.

11 Adam Lahm, “Looking Back,” 18.

12 Aisha Ali, “Looking Back: The California Middle Eastern Dance Scene (Pt. I: Hollywood Beginnings),” Arabesque 9:2 (1983): 6.

13 Ibid.

14 Ibid., 6-7.

15 Ibid., 8.

14 Ibid., 9.

17 See “Gilded Serpent Presents: North Beach Memories, The Venues: San Francisco, California, from 1960-1985,” Gilded Serpent, accessed January 12, 2013, http://www.gildedserpent.com/articles5/northbeach/places.htm, for more information about the nightclubs on and around Broadway in San Francisco, California.

18 Ali, “Looking Back,” 6.

19 Rasmussen, “An Evening in the Orient,” 179.

20 Ibid., 182.

21 Ibid., 184.

22 Ibid., 195.

23 Ibid., 196.