Habibi: Vol. 3, No. 11 (1977)

Drawings found in prehistoric caves show ritual dances depicting primitive men with spears raised overhead in ceremonial hunting dances, which preceded the actual hunts. Though still performed, some martial dances have lost their original significance.

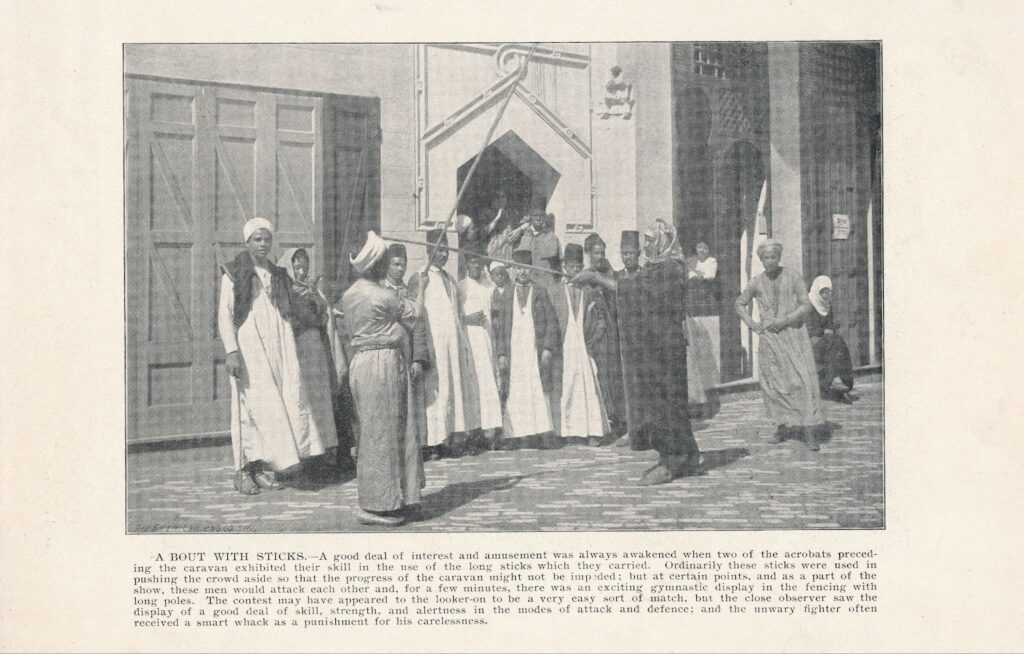

Modern Turkey boasts of a sword and shield dance which, when performed, is a throwback to the era when the participants were conscripts and mercenaries engaged in a death dance of choreographed military exercises. Stories of battle are pantomimed in a martial arts ritual using a spear, stick, cane, and sword.

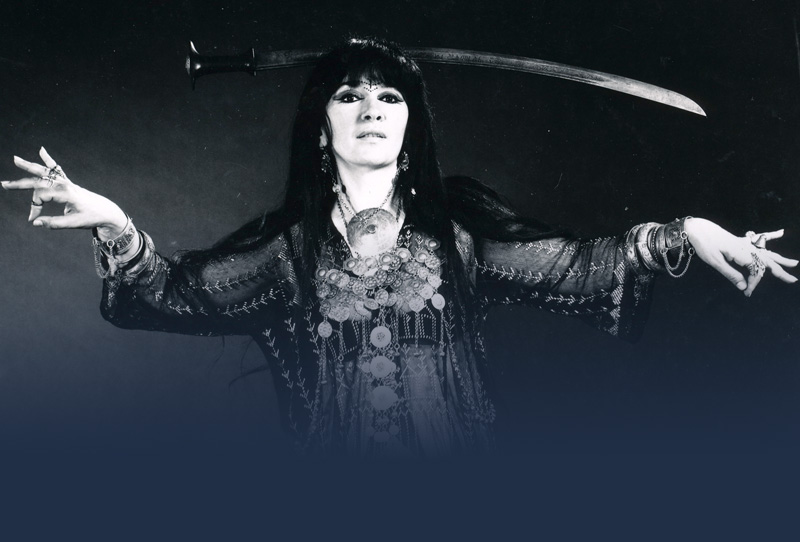

The Phyrric dance of ancient Greece was an important part of the military training curriculum. From early childhood, soldiers-in-training performed the quick tempo choreographed movements with shield and spear to flute accompaniment. By the third century AD it had been absorbed as one of the Dionysian dances in some areas and was performed with torches instead of weapons. The militant character and purpose of such choreographies changed when women performed the dances as entertainment. The classic example is seen in the paintings by Gérôme, the 19th-century French painter, who depicted a Ghawazee dancer entertaining an exclusive but admiring audience of military Turks. She uses their weapons in theatrical pantomime, effectively balancing a sword on her head while holding another in her right hand during her performance.¹

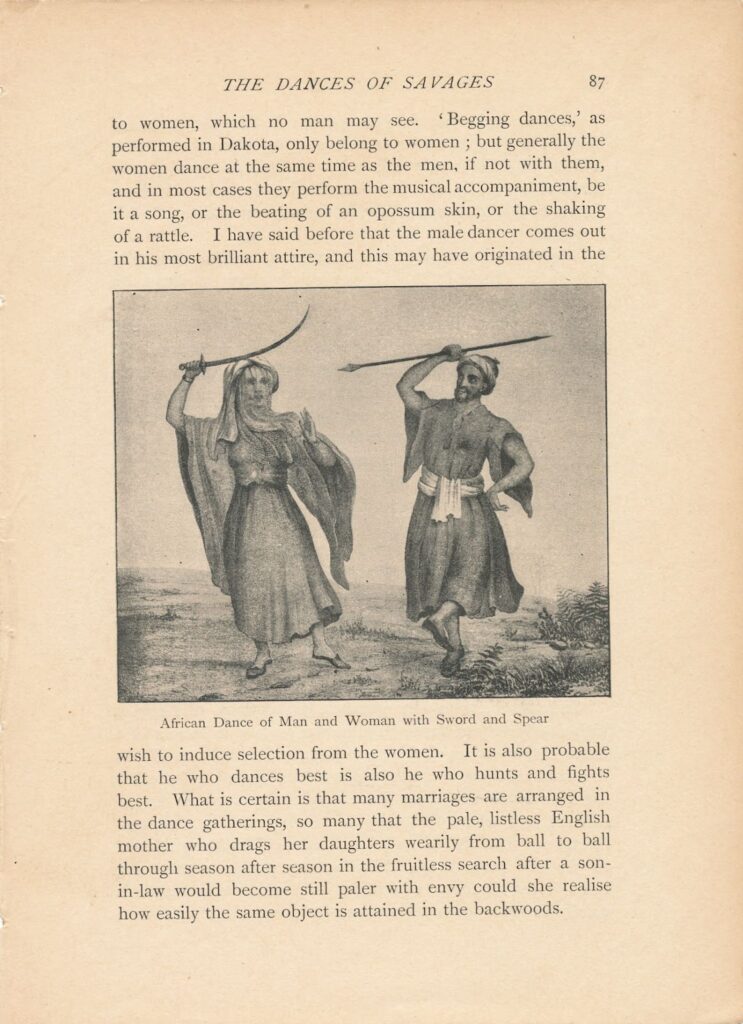

The sword, replaced by a stick, is the subject of a martial dance performed by the Ouled Naïl and described by Antoni Ferdynand Ossendowski who traveled extensively throughout Algeria and Tunisia in 1857. The women of the Ouled Nail are famous for their dances which are regarded as perfection of choreographic art. Although they are renowned for their performances of the danse du ventre, Ossendowski gives us a vivid account of their repertoire which includes a pantomime of the “Dance of Greeting and Farewell” known also as the “Dance of the Handkerchief”. Other dances of pre-Islamic origin are a survival of pagan days. The performance concluded with a dance of the sword, a true martial epic, a memory of bygone days. “In her outstretched hands she carried a stick to represent the sword” (the stick becomes equivalent to a sword though blunted). This is a very rare description of a martial dance-mime as performed by a professional dancing girl.

She fondled it caressingly, though with profound respect that showed itself in her mimicry and in the rhythm of her steps. Soon, however, this gave way to a rapid whirl, which she danced triumphantly, with her head raised proudly and her features flaming with courage. She waved the sword, held it aloft as though to heaven, and looked intently at its edge, recounting with her movements and gestures the history of the weapon, telling of the battles in which her hero swung this old, tired and ruthless blade, whereon perhaps there still remained the graven legend; Unsheathe me not without cause; Replace me not without honor. At last the dancer bowed to the invisible knight, and, like a slave, placed the weapon in his hands. The knight departed on his martial errand, while she remained with her face veiled in the silken Itam and hovered silently like a bird of night, anxious, grieved and sad. The tempo changed again. She whirled in joyous leaps, for her betrothed had sent her by the hand of a slave his treasured sword, the sword of victory. With the fellow-warriors of his tribe he would return on the morrow. A hymn of a woman’s pride and joy at the homecoming of her beloved bathed in victory followed the glad tidings. Tenderly she pressed the weapon to her lips, sought upon it the marks of the blood of his foes and kissed the hilt that had been held throughout the battle by her warrior’s strong and clever hand. ²

The men of the Ouled Naïl perform a stick dance, also martial in nature, similar to the tahtib dance which was performed by the Egyptian troupe brought to the United States by the Smithsonian Institute in 1976. ³

Rhythmic exercises have been included in military training throughout history. In Gaul, several muscular dances were used including sword dances. The ancient German military exercises included ring and sword dances. The ring dagger dance (from the Caucasus) led to precision knife throwing and similar demonstrations of skill rather than dance. The basic positions of both court modern ballet were derived from Spanish-Italian fencing. Court ballet combined several traditions including fencing to dictate ceremonial etiquette for the court. Each of modern ballet’s known “five positions” (as well as several common actions and technical terms) was part of the standard fencing technique before ballet was created. ⁴

The rich variety of provincial people brought to the Chicago World’s Faire included musicians, dancers, acrobats, scribes, barbers, candy vendors, merchants, and craftsmen. From Persia they brought an athlete who exercised using the Persian variety of Indian Clubs, accompanied by a drummer who played a large version of the zarb while chanting numerically, interspersing recitations from the Qur’an. An Algerian dancer using a sword was described:

Then the Algerine orchestra resumes its work as the wild drum beat ceases. One more gorgeous Arab girl dances a measure, holding a sword in one hand, which she swings in threatening contiguity to the heads of her crouching, yelling admirers. The waving blades, the swishing robes and draperies, and the rattling brass ornaments made in the aggregate a picture full of color and novelty, and one that calls forth the applause of the audience of coolly curious Americans. Then the whole company arise and with waving hands and swaying bodies sing a peculiarly plaintive chorus, that consists of but few tones and reminds one of a Gregorian chant.

A sword dance resembling more of Scotland than Egypt was performed by a Ghawazee for Jeremiah Lynch, an Englishman, while he was visiting Cairo in 1889. He included a brief and unimpressive description in his memoirs: “A pair of drawn scimitars was simply placed crosswise on the rug, and the dancers, two in number, interlaced arms and, waving with their free hands scarlet silken handkerchiefs, lightly tripped between the weapons. It is graceful, but by no means dangerous, feat; for, though the scimitars have bright surfaces, the distance between them is ample, and the Ghawazee’s unsandaled feet are small.” ⁶

The cane dance, using a shepherd’s crook, is the familiar prop of a folk singer from the Middle-East. Monologists, in the popular village dress, will sing favorite village songs with tunes that have been around since nobody can remember when. With his or her own jokes added to the old lyrics, they will keep an audience dangling until the punch line can be dramatically and effectively delivered. While the audience is laughing, they will raise the crook aloft and execute a series of folk steps while waiting for the laughter to subside and for sufficient calm to begin yet another tale.

The cane, crook and staff are sometimes used to represent power or force or, as in martial dance, an object for defense.

Middle Eastern martial dancing is indeed a very ancient art. We can see in the dance of today remnants of its origins that have evolved into a graceful dance which gives pleasure to performer and audience alike. In understanding the history, we appreciate the dance all the more.

This article was published in Jamila’s Article Book: Selections of Jamila Salimpour’s Articles Published in Habibi Magazine, 1974-1988, published by Suhaila International in 2013. This Article Book excerpt is an edited version of what originally appeared in Habibi: Vol. 3, No. 11 (1977).

¹ Walter George Raffe, Dictionary of the Dance (New York: A. S. Barnes, 1965)

² Ferdinand Ossendowski, Oasis and Simoon: The Breath of the Desert; The Account of a Journey through Algeria and Tunisia (New York: E. P. Dutton, 1927).

³ Around the World in 2,000 Pictures. Doubleday, 1959.

⁴ Raffe, Dictionary of the Dance.

⁵ The Columbian Gallery: A Portfolio of Photographs from the World’s Fair (Werner Company, Chicago, 1894).

⁶ Ossendowski, Oasis and Simoon.

Photo Credits:

- Greek Dancing Lessons, line drawing from a vase painting in the British Museum, circa 450 B.C., page 372, The Antique Greek Dance, Maurice Emmanuel, translated to English in 1916, Public Domain.

- Rahlo Jammele, Jewish Dancing Girl, Unknown American Photographer, Oriental and Occidental Northern and Southern Portrait Types of the Midway Plaisance, by N.D. Thompson Publishing Company, 1894, Creative Commons, Photograph © Daniel D. Teoli Jr. – License: creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

- A Bout With Sticks, Unknown Photographer, late 1800s, Public Domain.

- Turkish Swordsmen, Midway Plaissance, World’s Columbian Exposition, Unknown Photographer, 1893, Public Domain.

- Ouled Nail Dancer with Sword, Unknown Artist, Public Domain.

- African Dance with Sword and Spear, Unknown Artist, Public Domain.

- Sword Dancer of Bal Anat, Anne Lippey, 1975.