- A History of Middle Eastern Music

- Genres of Music and the Ensembles that Perform Them

- The Great Four of Arabic Music

- Western and Middle Eastern Music Theory

- Introduction to Western Notation

- Middle Eastern Rhythms

- Middle Eastern and North African Instruments

Western and Middle Eastern Music Theory

This chapter will examine some of the main elements of music—how it is organized and created, including a very brief look at Western musical notation—to give a sense of musical scales (collections of ascending and descending notes). We will first look at Western music, and then at Middle Eastern music.

Qualities of Music

Music, both in the West and in other areas of the world, is characterized by certain key concepts and ideas. Familiarity with these concepts is crucial to gaining an understanding of how music works.¹ The composer Aaron Copland identifies four qualities in a given piece of music: rhythm, melody, harmony, and tone color.²

Rhythm

The pulse or beat of a given piece of music. This also includes tempo, or how “fast” or “slow” the music seems to the ear.

Melody

Melody is the arrangement of single, successive notes that create a distinctive sequence or tune. Virtually all music is based on melody and melodic composition.

Harmony

The study of the structure, progression, and relation of chords, that is, two or more notes sounding together simultaneously. Also, it describes the combination of notes to make a chord. The vast majority of Western music is based on chords.

Tone color

Also known as timbre, this refers to the varieties of sound that can be produced, both by the human voice and by musical instruments. We can recognize that a female soprano voice sounds different from a male bass voice or that a violin is different from a piano. These are the different tone colors. Think of them as being like colors in a painting, or like the use of light or darkness.

After identifying these qualities, one must also consider the texture of music, which will vary widely depending on its origin, the type of music, the composer’s and musician’s styles, and any number of other factors.

Musical Texture

The texture of a musical composition is formally described based on the relationship of melodies and harmonies. The terms are monophonic, homophonic, polyphonic, and heterophonic.

Monophony

Monophony is based on a single melody. The music has one melody line without harmony (but might include basic percussion). Examples include the a cappella singer (a single voice); a solo instrument; or a choir singing a melody without harmony or counterpoint. Gregorian chant is an example. Many folk songs are also sung this way, and traditional Middle Eastern music played by a single instrument is very often monophonic.

Homophony

One singer (or instrument) takes the featured melody; the other voices (or instruments) take the supporting role of singing harmony to support the featured melody. Much Western music written after 1600 is homophonic.

Polyphony

More than one independent melody occurs at the same time. Each melody line can be removed from the other and stand alone. This was the standard method of composition in the West until about 1600, though later composers, such as Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) made spectacular use of its effects. Polyphony is not exclusively a Western innovation, but is more commonly found there than elsewhere.

Heterophony

Heterophonic music contains only one melody, like monophony, but different variations of the melody are sung or played at the same time. As an example, two instruments will play the same melody, but each musician adds embellishments or flourishes characteristic of the individual instrument. Texture is created by simultaneous performances of different versions of the same melody by different voices and/or instruments. Heterophonic music is often improvised or based on oral traditions, and is common in Middle Eastern music ensembles.

Scales in Western Music

Before we can explore the maqām (musical modes) in Middle Eastern music, we must first introduce the concept of musical scales.

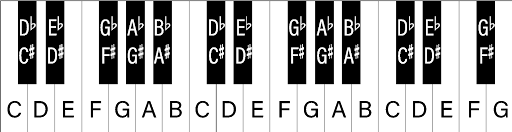

In Western music, individual notes have letter designations: A through G. On a piano, these are the white keys. There are also notes between these, which are represented by the black keys. These are sharps (♯) or flats (∫), depending on their relationship to their adjacent whole note (white key); a sharp raises a note by one half tone, while a flat lowers it by one half tone.

These notes can be organized in groups of eight notes each, known as scales, which are an essential element of Western music. Scales have patterns of certain ascending and descending notes that give each scale a specific identity. After every seven ascending or descending notes, the scale begins again with the same starting note, only one that sounds higher or lower.

These groups of notes are known as octaves, from the Latin octavus, or “eighth,” because with every eighth note, the scale begins again. For example, the scale beginning on the C note (the scale that most beginning piano students learn to play first) would ascend C-D-E-F-G-A-B before ending on C again. Thus, in the ascending scale: C-D-E-F-G-A-B-C, the last C notes is said to be one octave higher than the first. The two C notes sound similar because they have similar vibrational frequencies; the sound waves created by middle C (where we began) vibrate twice as fast as the C an octave below it, and at half the speed as the C one octave above it.

There are many different kinds of scales, such as major, minor, augmented, diminished, and pentatonic. A scale’s seven ascending or descending notes are subdivided by whole steps and half steps in different ways to give each scale a particular character, identify, and sentiment.

This combination of the particular starting note and the arrangement of the upward and downward steps of the scale is said to be the “key” of the song. So, a song beginning (and more importantly, ending) on a C note (or a chord created from that note), with the appropriate arrangement of whole and half steps in the notes of its scale, would be said to be in “C major” or “C minor,” or whatever it might be.

If a scale starts on D, but its notes have the same relationship to each other in descending or descending as if they started on C, the key would be D major or D minor, to compare to the previous example. This is true for every note. So, A major and F major have the exact same scale, only they start on different notes. C minor and G minor are likewise the same, except for where they begin.

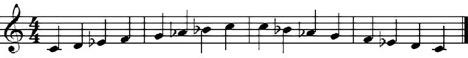

The following music example shows the ascending and descending scale for the key of C major:

In the example above, the ascending C major scale is defined as: C to D, a whole tone; D to E, a whole tone; E to F, a half tone; F to G, a whole tone; G to A, a whole tone, A to B, a whole tone, B to the final C, a half tone. The same note relations exist in the descending scale.

The next example is in the key of C minor. You can see that several of the notes have been altered with a flat sign, lowering those notes by a half of a tone. These flats change the character of the scale completely:

When you hear a composition, such as “piano concerto in F major”, it means the composer structured the piece around that scale, beginning and ending on the F note. The compositions might stray away from that scale (and many often do) into other keys, scales, or variations, before returning to F major, but that designation helps to define what the piece is and where it rests melodically and harmonically.

Western music from about 1600 onward is based around these concepts of scales and keys.

Maqām

Middle Eastern music (as well as music from the European Middle Ages and Renaissance) is modal. Modes are similar to scales, with designated sets of ascending and descending notes, but they are not so tied to specific keys. We do not talk of the “A major mode” for example, though the concept is similar. A given mode can begin on any note, and as long as the relationships between its ascending or descending notes remain the same, it is considered to be the same mode.

In Middle Eastern music—Arabic and Turkish—each mode is called a maqām (pl. maqāmāt). Understanding maqām fully takes musicians years of study, but dancers can benefit from understanding the basics of maqām and how they are used in Middle Eastern music. Maqāmāt resemble scales, since each maqām is made from specific musical notes.

Maqāmāt also include melodies, phrase, and/or other patterns that are found in that specific mode and not others. Each maqām has its own characteristics,³ and many experts on Middle Eastern music say that each maqām suggests specific moods or emotions. As Touma notes, “The maqam phenomenon, a technique of improvisation unique to Arabian art music, is at the root of all genres of improvised vocal and instrumental music of the entire Arabian world, in secular as well as in sacred music.” ⁴

As with Western scales, melodies are composed using these various modes. Normally a piece will begin and end in the same maqām, though sometimes they will stray into others for a portion of the musical piece.

In Western music, each note has a half step (half tones) between it and the next note. These are tuned and placed precisely at exact intervals.

Middle Eastern music has quarter tones or microtones, thereby dividing the scales even further with more notes. But these notes are not necessarily placed at exact intervals (equidistant) between the notes. Instead, based on the maqām on which the music is based, those intervals will be adjusted slightly sharper or flatter to fit the given maqām.⁵ If you are familiar with the layout of a piano keyboard, think of these as subtle notes between the white and black keys of the keyboard.

Middle Eastern music generally does not use the Western letter-names for its notes (A, B, C, etc.), but has its own Arabic names, as well as the Western note-naming system known as solfège: Do, Re, Mi, Fa, Sol, La, Ti, Do. The solfège derives from medieval music theory and is over 1,000 years old. It is still commonly used in music schools, and if you’ve ever seen the musical or movie The Sound of Music, you’re probably familiar with it.

Microtones and their use in Middle Eastern music is a complex subject, but it is enough to know that certain such tones are characteristic of certain maqāmāt. If you did not grow up listening to Arabic or Turkish music, you will undoubtedly recognize that these scales might sound different, unlike what you are used to hearing.

Indeed, for many in the West, these notes actually sound out of tune or incorrect. Far from being incorrect, they are actually based on complex mathematical ratios between notes, some of which can be dated back to music theorists in ancient Greece.⁶ They are a common feature of music throughout the Middle East, extending into Iran and even India, and have such prominence because the music from these regions tends to be mostly melodic, rather than harmonic. Indeed, so important are the tone relationships in a given maqām, that they take precedence over the rhythmic structures of a piece of music.⁷

The following two musical examples illustrate the basic progressions of notes in two common Arabic maqāmāt, hijāz and bayāti. Hijāz is perhaps the most famous of the Middle Eastern modes, its note progression being used in most Western portrayals (film, orchestral music, pop music) to create a “Middle Eastern” feel. Hijāz is also popular in Western interpretations of Middle Eastern music because it does not contain quarter tones.

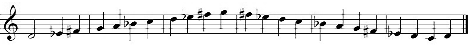

Bayāti contains quarter tones, marked in this example by a diagonal line through the flat sign. This is a standard way of indicating such tones in Western notation. This maqām is quite popular in all types of Middle Eastern music, and displays the characteristic “non-Western” sound that can seem odd to the first-time listener:

In both of these cases the ascending and descending notes of the mode are the same, but this is not true of every maqām. In some, the singer or instrumentalist will produce certain tones when the melody rises, but different tone when it descends.

These maqāmāt are also the names for specific “genres” of other maqāmāt, that is, other modes that are similar in sound, and are a part of the same family of maqāmāt. The hijāz maqām genre, for example, contains related maqāmāt such as hijazkar, shahnaz, and shadd ‘araban, while the maqām bayāti genre includes related maqāmāt such as husayni sabā, and muhayyar.⁸ Historically, there were more than hundred maqāmāt though in practice today, only about 20 are used.

Most importantly for the dancer, each maqām is said to evoke certain emotions in the musician and in the listener. When interpreting the sentiment of an Arabic song, the emotional content of the maqām is paramount, even to the lyrics or poetry of that particular song. Bayāti evokes feelings of “vitality, joy, and femininity,” while hijāz “conjures up the distant desert.” ⁹ Of course, those who have grown up listening to Arabic music will have different interpretations of each maqām, but there are universal themes and feelings. Sabā, for example, is often considered to be the most profound and sad of all the maqāmāt.

The informed listener will be able to identify the specific maqām of a piece and therefore understand the mood that it is trying to communicate.

What follows is a list of the most commonly-used maqāmāt, and some of the meanings and emotions associated with them, as well as a popular Middle Eastern song that uses the particular maqām. Note that the song titles are transliterated in more common spellings rather than strict letter-for-letter equivalents.

Rāst: pride, soundness of mind, cheerful, positive, elegant, stately, romantic.

Example: Ghanili Shwayya Shwayya

Bayāti/Uşşak: vitality, joy, uplifting feeling.

Example: ‘Ala Baladi Al Mahbub

Sabā: sadness, tragedy, pain, but also mysticism, the “blues” of Arabic music, can also convey happier moods when played fast.

Example: Salametha Umm Hassan

Sīkah/Huzām: love, youth, strength, originally known as the “music of the mountains.”

Example: Sections of Al Atlal

Nahāwand: changes of emotion, feelings, passionate, often used in love songs.

Example: Alf Layla Wa Layla

Ḥijāz: the desert, caravans, enchantment, the most stereotypical “Middle Eastern” mode.

Example: Zeina

Kurd: airy and spacious, and creates the feeling of freedom.

Example: ‘Aziza

‛Ajam: bright, happy, majesty, loftiness, national anthems, strength.

Example: Shams Al Shamouseh

Unfortunately, there is often little agreement on the exact mood for each maqām. Descriptions can vary and be vague, as you can see from these descriptions (i.e., “love,” “youth,” “pride,” and “airy”). To date, there have not been many studies to try to categorize the moods of the maqāmāt or get a consensus. A few surveys have yielded inconclusive results, but show that Arab and non-Arabs may hear a given maqām differently.

¹ A very useful guide is Aaron Copland’s What to Listen for in Music (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1957, reprinted 1988). Though focused mainly on classical music, it provides an excellent introduction to the key concepts of music and how to listen in an informed way.

² See ibid., 33-100, for a detailed chapter devoted to each quality.

³ For a more detailed survey of the maqām, see Marcus, Scott L. Music in Egypt: Experiencing Music, Expressing Culture. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006, pp. 16-22.. This book has a companion CD with many useful examples. Listening to these is essential to understanding how maqāmāt truly work. See also the excellent introduction in Touma, Habib Hassan. The Music of the Arabs, translated by Laurie Schwarts. Portland, OR and Cambridge, UK: Amadeus Press, 1996, pp. 16-45.

⁴ For a more detailed survey of the maqām, see Marcus, Music in Egypt, 16-22. This book has a companion CD with many useful examples. Listening to these is essential to understanding how maqāmāt truly work. See also the excellent introduction in Touma, Music of the Arabs, 17-45.

⁵ See Marcus, Music in Egypt, 26.

⁶ For more on the relationship between Greek and Arabic music theory, see Touma, Music of the Arabs, 17-18.

⁷ Ibid., 38-39.

⁸ For a detailed examination of the main maqām genres, see Touma, Music of the Arabs, 29-37, which illustrates many more maqāmāt in notation. See also Sawa, George Dimitri. Egyptian Music Appreciation. Toronto: Music Manufacturing Services, 2010, pp.14-17, for notation examples of the eight most popular maqāmāt, which also have musical examples on the accompanying CD.

⁹ See Touma, Music of the Arabs, 43-44, which also list the feeling associated with several other maqāmāt.

Pillar page

The content from this post is excerpted from Middle Eastern Music: History & Study Guide. A Salimpour School Learning Tool published by Suhaila International in 2018. This Music Book is an introduction to the music theory and main music exponents in the history of belly dance.

If you would like to make a citation for this article, we suggest the following format: Keyes, A. and Rayborn, T. (2018). Music Theory. Salimpour School. Retrieved insert retrieval date, from https://suhaila.com/music-theory