Although Jamila herself often used the terms ‘alma/‘awalim, ghawazi, and Ouled Nail interchangibly to mean a woman who dances, these terms actually describe different groups of female entertainers. Some of the first accounts of these groups of singers, musicians, and dancers come from European travelers’ journals and letters as they visited North Africa and Egypt. In this section we will introduce the three main designations of female entertainers, definining each and providing background on their skills, status, and characteristics.

‘Awalim and Ghawazi

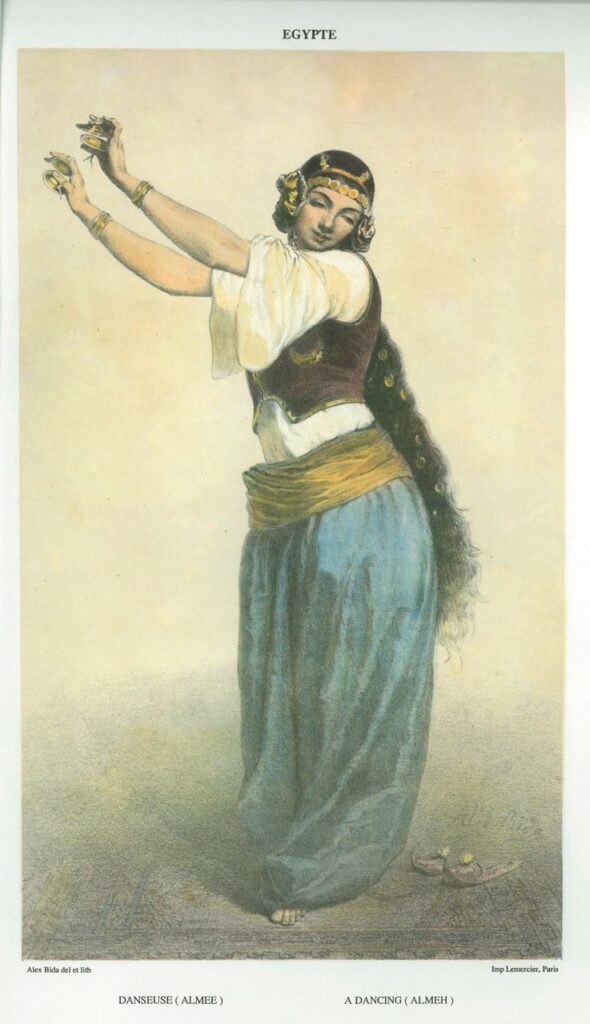

‘Awalim, singular ‘alma (sometimes transliterated as ‘almeh), literally means “learned women,” meaning they were educated in the arts of singing, poetry, music composition, playing musical instruments, and performance. Scholar Natalie Smolenski points out that the word is the feminine counterpart of ‘alim, which is “the title given to male religious scholars;” indeed, she says, “many of these women were well versed in subjects of religion in addition to their musical and literary training.”¹

According to English traveler Edward Lane who lived in Egypt at the turn of the 20th century, the ‘awalim were often highly paid, respected, and wealthy women would invite them into their homes to entertain their families. The ‘awalim performed mostly for the women of the harem² (the women’s living quarters), and were allowed to go in and out of the harem without needing permission.³ Lane notes that the ‘awalim would perform “on the occasion of any great rejoicing among the women,” such as “the birth of a son,” “circumcision,” or “a wedding.”⁴ Scholar of Egyptian dance history Marjorie Franken says that in the late 19th century, “the awalim and the ghawazi were poles apart in their social acceptability and adherence to the conventions of female seclusion.”

The ‘awalim were allowed in the harems of the upper-class,⁵ and to protect the ‘awalim’s honor in the presence of men, male family members and guests would have to listen to their singing on the other side of a mashrabiyya—a window covering of intricate lattice work through which it is difficult to see—or the women would play on a balcony over an inner courtyard, so that the men could hear their music, but not see them play. The ‘awalim would participate in wedding celebrations, but only as singers, never as dancers. They might have attended bride’s private wedding parties, such as her henna night.⁶

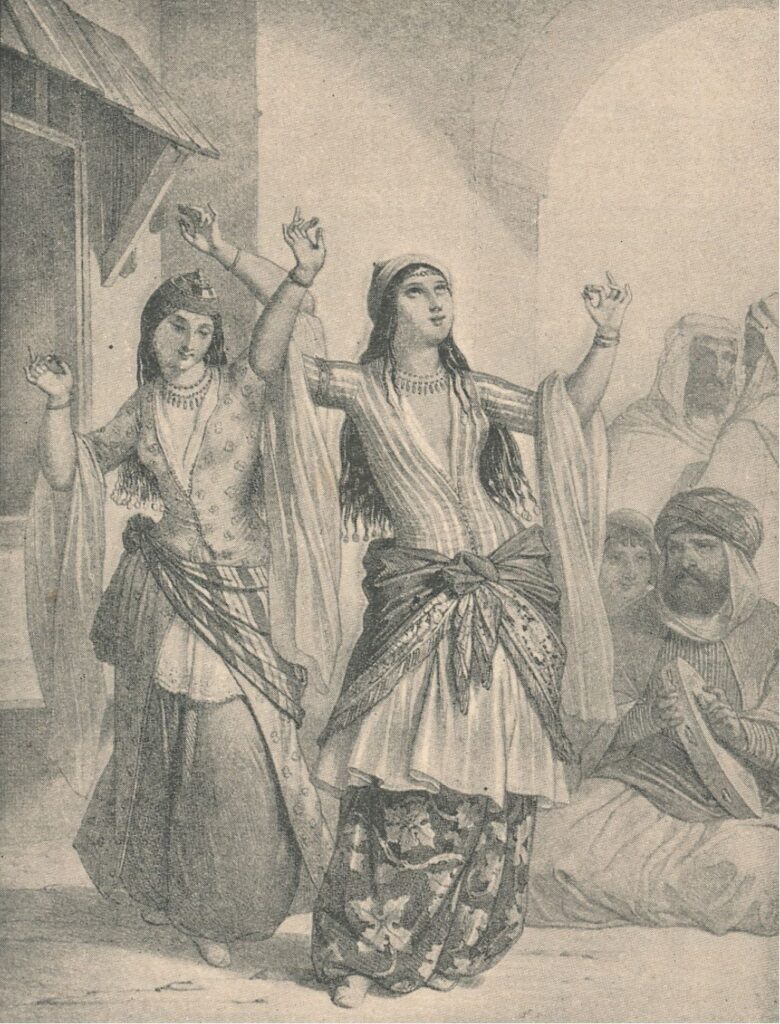

The ghawazi, unlike the ‘awalim, performed in public, and were generally viewed by Egyptian society as disreputable, as they performed unveiled in public, often in front of coffeehouses.⁷ They also smoked the water pipe and drank “considerable amounts of brandy.” In general, Egyptian society did not regard them as “decent women.”⁸ They followed the mawlid, saint’s Day, celebrations that often include carnival-like entertainments. Early travelers described them as dancers only, not as prostitutes, a distinction that changed later. Finger cymbals were, and continue to be, an integral part of their performances; they were also known to have danced with a variety of props,⁹ such as scarves, sticks, and candles.¹⁰ They were sometimes hired to perform outside of wedding celebrations, but never inside, and often the morning after the dakhla (consummation).

The ghawazi (singular ghaziya) are thought to be descended from the Romany tribes who settled in Egypt as early as the 5th century. In fact, their name implies an outsider status; ghazi means “invader” in Arabic.¹¹ Like other dancers in the Middle East, the earliest record we have of them is from European travelers in the region no earlier than the 18th century. Marjorie Franken says that in 1817, one traveler estimated there were 6-8,000 ghawazi in Egypt. ¹² Travelers’ accounts from this time describe them as looking and dressing differently from other Egyptians, and nearly every European who encountered them was fascinated by their unfamiliar and “strange” dances. Traveler Edward W. Lane said the ghawazi performed “unveiled in the public streets,” and their dancing had “little of elegance,” with its “chief peculiarity being a very rapid vibrating motion of the hips from side to side.” ¹³ In his novel, Askaros Kassis the Copt, Edwin de Leon, wrote in 1870 that the ghawazi “writhed and twisted their lithe bodies and sinuous limbs in strange muscular contortions—into almost impossible positions—keeping time to the music with every motion.” ¹⁴ Travelers in the early 19th century, according to Marjorie Franken, “did not describe the ghawazi dancing girls as prostitutes,” however this is a distinction that would change in the mid-1800s.

As the French and British armies took greater interest in Egypt in the early 19th century, the ‘awalim were increasingly described as singers who were sometimes dancers, and the ghawazi as dancers and who were sometimes prostitutes. Edward W. Lane in 1908 wrote that the ghawazi were “the most abandoned of the courtesans of Egypt.” ¹⁵ As more Europeans frequented Egypt female entertainers made themselves more visible, taking advantage of the new clientele in the foreign soldiers and travelers. ¹⁶

The Egyptian leadership, still vassals of the Ottoman Empire, increased their taxes on the female entertainers, seeing them as a steady source of revenue for the state. However, Muhammad ‘Ali Pasha, self-declared leader of Egypt with the Ottoman’s temporary approval, was eager to please the religious authorities who objected to a tax on vice and to portray Egypt as a more European-style country; he banished the public female entertainers (and prostitutes) from working in Cairo in 1834. If they were not deported, then they fled, particularly to Esna, Qena, and Luxor (Upper Egypt). It was there that they turned increasingly to prostitution, partly because of the requests of foreign tourists who followed them there, but also because of the poverty the dancers faced in Upper Egypt. ¹⁷

Initially, the status of the ‘awalim was not as negatively affected by the ban as was that of the ghawazi. Van Nieuwkerk says the “higher-class ‘awalim could continue their usual activities,” such as “singing and making music in the harems.” She says that “it is possible that singing and dancing on special occasions such as native weddings was still allowed in Cairo.” ¹⁸ Eventually, however, the position of the ‘awalim fell from respectable to fallen, and the terms ‘awalim and ghawazi appeared to be used interchangably. One traveler, H. de Vaujany, noted in 1883 that “the almehs have fallen from their earlier position; they have come down to the rank of the most vulgar courtesans.”¹⁹ Van Nieuwkerk, too, says that “the word ‘alma completely lost its original meaning of learned woman,” and “by the 1850s it denoted a dancer-prostitute.” ²⁰

Before Muhammad Ali banished the ghawazi and ‘awalim from Cairo, Van Nieuw-kerk says that there was also an unnamed third category of female entertainers between the two in class and status. They were from lower-class families and performed in working-class neighborhoods. ²¹ This third group of performers might have contributed to the confusion between the two terms, and why some people have used them interchangeably.

The “dancing girls” returned to Cairo when Abbas Basha lifted the ban in the 1850s, probably in order to levy taxes on their earnings once again, but were not allowed to perform publicly except on special occasions. Despite these restrictions, however, there was still an abundance of female entertainers. When the British declared a protectorate in Egypt in 1882 and directed the Egyptian government for all intents and purposes, they sought to regulate entertainment, such as those at the mawlid saint’s days and at cafes. The “cafe-chantant” became the new venue of choice, where dancers and singers could be hidden from the public, and entertainment could be “increasingly institutionalized and regulated.” In 1869, Khedive Ismail built an opera house in Cairo, in Ezbekiyyah Gardens, to provide an “area of familiarity and amusement for the growing number of European professionals in Cairo.” ²² These café-chantants and the push for more European-style venues eventually gave rise to nightclubs that showcased “native dancing,” and as Van Nieuwkerk notes, “at the turn of the century, the local dancing, for the first time, was called belly-dancing.” ²³

Ironically, when the “dancing girls” returned to Cairo, they settled on Muhammad ‘Ali Street, a long boulevard constructed to connect the citadel, once the traditional seat of the government, to the new palace and Ezbekiyyah Square in Cairo’s new European district. Both Franken and Van Nieuwkerk provide excellent accounts of this new center for entertainment. Van Nieuwkerk tells us that Muhammad ‘Ali Street “consisted of music shops” selling instruments, as well as cafes and “agencies for parties.” She also notes that at the beginning of the 20th century, wedding celebrations were still gender-segregated, creating a demand for all-female musical ensembles and dancers. Under the management of the usṭa—an experienced and older woman who was once or still was a performer—women, still called ‘awalim, could find performance work and eventually become an usṭa herself. ²⁴ The ‘awalim would travel to their work veiled, as they would before the banishment.

In the 1930s and 1940s, the ‘awalim faded from Cairo’s entertainment scene. Wedding celebrations became “less segregated and less extravagant,” and “people either abolished professional entertainment at the women’s party or allowed female guests to be present at the men’s party.” In addition to social changes, economic and political strife in the 1930s spurred a religious revival in Cairo, and in the 1940s the Muslim Brotherhood and fundamentalist groups attempted to ban the mawlid celebrations, claiming that they were un-Islamic. President Gamal Abdel Nasser repressed the religious groups, reviving the festivals in the 1950s, but by this point the ‘awalim had effectively vanished. Muhammad ‘Ali street began to decline in the 1970s, as economic strife struck Egypt and those seeking entertainment turned to nightclubs or recorded music. ²⁵

While the tradition of the ‘awalim has faded, the ghawazi continue to perform in Egypt. According to researcher Sahra Kent, only five ghawazi groups remain, the most famous of them being the Benat Mazin in Upper Egypt, and their matriarch, Khayriyya Mazin.

The Ouled Nail

Much less is known about the women of the Ouled Nail (pronounced “waled nah-eel”) tribes (Laghouat, Ghardaia, Ouargla, and Biskra) who lived in Algeria, between Biskra and Laghouat. Even though the term is often used interchangeably with “ghawazi” to mean a generic “dancing girl,” the women of the Ouled Nail have no discernable relation to the performers of Egypt. The women of these tribes learned to dance at an early age, and then they reached puberty, left home, accompanied by an older woman of their tribe, to travel to more urban areas to earn money dancing, playing music, and often working as prostitutes at the oases to begin a new life. When they had earned enough money for their dowry and other living expenses, they would stop working and marry, then teach their daughters how to dance;²⁶ some never returned home, choosing to use their earnings to stay in more cosmopolitan areas.²⁷ They were primarily known for the pleasurable entertainments of all sorts—dance, conversation, and sex—they could offer men who seldom had a chance to spend time with more cosmopolitan women than their secluded female relatives.²⁸ Ouled Nail researcher Andrea Deagon says they were “women who were sexually active outside of the bonds of marriage and women whose lovers expected to have to support them and give them gifts.” In this way, they were not prostitutes in the way that we might define the word. Deagon also notes that not all female members of the tribe became dancers, but young women were the center of a household’s finances and public life.²⁹

Made famous by French artists living and working in Algeria in the 19th century, they were frequently photographed, painted, and immortalized in travel writing. Traveler Helen C. Gordon wrote in 1915 that the Ouled Nail was “a great tribe, founded at the end of the 16th century by a famous saint, Sidi Nail.”³⁰ The French fascination with the Ouled Nail made the city of Bou Saada a tourist site, and many other visitors to Algeria saw them dance. ³¹ Lewis Wingfield wrote in 1868 that the Ouled Nail “are the institution of the desert par excellence.” He also says that they “are a much-honoured race,” with no wedding being “complete without their presence.” ³²

They were also known for their elaborate costumes, heavy with coins and fabric. Lewis Wingfield wrote three pages describing their costume, which he said was “overloaded with clothes” and a “tangled mass of long draperies and handkerchiefs and chains.” He also writes that they wore “yards of silver chains about their necks and waists […] while the wealthier damsels have, in addition to all this, magnificent necklaces of coral and silver beads.” ³³ Contemporary writers on Oriental dance claim it was probably their practice of dancing for “dowries” and wearing their earnings on their clothing that contributed to the use of coins in the Westernized belly dance bra and belt. They practiced this custom until the 1930s. ³⁴

Since the 19th century, the Ouled Nail have been in great decline, mostly because of colonial influence and conflict in the region. Andrea Deagon notes that “one of the historical forces that led to the erosion of the Nailiyat’s prosperity as professional dancers was their definition as prostitutes by French officials.” That said, she says that the Ouled Nail still exists, and under some circumstances, continues to dance publicly. ³⁷

The content from this post is excerpted from The Salimpour School of Belly Dance Compendium. Volume 1: Beyond Jamila’s Articles. published by Suhaila International in 2015. This Compendium is an introduction to several topics raised in Jamila’s Article Book.

If you would like to make a citation for this article, we suggest the following format: Keyes, A. (2023). Dance in the Middle East. Salimpour School. Retrieved insert retrieval date, from https://suhaila.com/dance-in-the-middle-east

1 Smolenski, “Modes of Self-Representation,” 55.

2 Karin Van Nieuwkerk, ‘A Trade Like Any Other’: Female Singers and Entertainers in Egypt (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 1995), 26.

3 Nelly Mazloum, “The Enduring Mystique of the Almeh,” Habibi 13:3 (1994), accessed December 28, 2013, http://thebestofhabibi.com/vol-13-no-3-summer-1994/almeh/.

4 Edward W. Lane, Manners and Customs of the Modern Egyptians (London: J. M. Dent and Co: 1908), 195, accessed December 28, 2013, https://openlibrary.org/books/OL29705M/The_manners_customs_of_the_modern_Egyptians.

5 Marjorie Franken, “From the Streets to the Stage: The Evolution of Professional Female Dance in Colonial Cairo,” in Leisure in Urban Africa, ed. Paul Tiyambe Zeleza and Cassandra Rachel Veney (Trenton, New Jersey: 2003), 89.

6 Carolee Kent and Marjorie Franken, “A Procession Through Time: The Zaffat al-cArusa in Three Views,” in Images of Enchantment: Visual and Performing Arts of the Middle East, ed. Sherifa Zuhur (Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press, 1998), 76.

7 Van Nieuwkerk, ‘A Trade Like Any Other’, 26.

8 Van Nieuwkerk, “Changing Images and Shifting Identities: Female Performers in Egypt,” in Moving History/Dancing Cultures: A Dance History Reader, ed. Ann Dils and Ann Cooper Albright (Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press, 2001), 137.

9 The practice of dancing with a shama’dan, a candelabra of burning candles worn on the head, and associated with the wedding procession, likely has its roots in the use of props by the ‘awalim. The typical shama’dan performance involves leading the wedding procession, and then a performance; this kind of Egyptian dance is one of the few that allows for floorwork, as the dancer will often perform the splits with the shama’dan on her head. The ghawazi were also known for balancing various objects on their heads, or in their teeth, as in the performance by Princess Rajah from 1904 at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition (see http://youtu.be/pp7uulaxQA8, accessed January 6, 2015).

10 Van Nieuwkerk, ‘A Trade Like Any Other’, 27.

11 Some scholars argue that the name comes from the word ghawa, meaning, “to seduce,” but by leaving out the “z,” this ignores the triliteral root system inherent to the Arabic language.

12 Franken, “From the Streets to the Stage,” 92.

13 Lane, Manners and Customs, 384.

14 Edwin de Leon, Askaros Kassis the Copt (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co, 1870), 104-5, accessed December 29, 2014, https://openlibrary.org/books/OL20611386M/Askaros_Kassis_the_Copt_A_Romance_of_Modern_Egypt.

15 Lane, Manners and Customs, 386.

16 Van Nieuwkerk, ‘A Trade Like Any Other’, 31.

17 Van Nieuwkerk, “Changing Images,” 137.

18 Ibid., 33.

19 Quoted in Mabro, Veiled Half-Truths, 131.

20 Van Nieuwkerk, ‘A Trade Like Any Other’, 35.

21 Ibid., 27.

22 Franken, “From the Streets to the Stage,” 95.

23 Van Nieuwkerk, ‘A Trade Like Any Other’, 36-9.

24 Ibid., 50.

25 Ibid., 52-7.

26 Wendy Bounaventura, Serpent of the Nile: Women and Dance in the Arab World (Northampton, Massachusetts: Interlink Books, 2010), 87. The images and photographs in this new edition of the popular belly dance book are lovely; however, the book has spotty references and citations.

27 Khedi, “Tribal Custom, the Quran and Revolution: The Changing Role of Women in Algerian Society,” Habibi 18:2 (September 2000), accessed December 28, 2013, http://thebestofhabibi.com/volume-18-no-2-september-2000/women-in-algerian-society/.

28 Andrea Deagon, “Dancing for Dowries: Earning Power, Ethnology, and Happily Ever After,” Gilded Serpent, August 16, 2009, accessed December 28, 2013, http://www.gildedserpent.com/cms/2009/08/16/andreadanc4dowries2/#axzz2g9HKgVHF.

29 Ibid.

30 Helen C. Gordon, A Woman in the Sahara, (New York: Frederick A. Stokes, 1914), 123, acessed December 18, 2013, https://openlibrary.org/books/OL6570485M/A_woman_in_the_Sahara.

31 Deagon, “Dancing for Dowries.”

32 Lewis Wingfield, Under the Palms in Algeria and Tunis, (London: Hurst and Blackett, 1868), 42, accessed December 18, 2013, https://archive.org/details/underpalmsinalg01winggoog.

33 Ibid., 43-6.

34 C. Varga Dinicu, You Asked Aunt Rocky: Answers & Advice About Raqs Sharqi & Raqs Shaabi (New York: RDI Publications, 2013), 75.

35 Ted Shawn, Gods Who Dance (New York : E.P. Dutton & Co., 1929), 69.

36 Wingfield, 66-7.

37 Andrea Deagon, “Dancing for Dowries.”