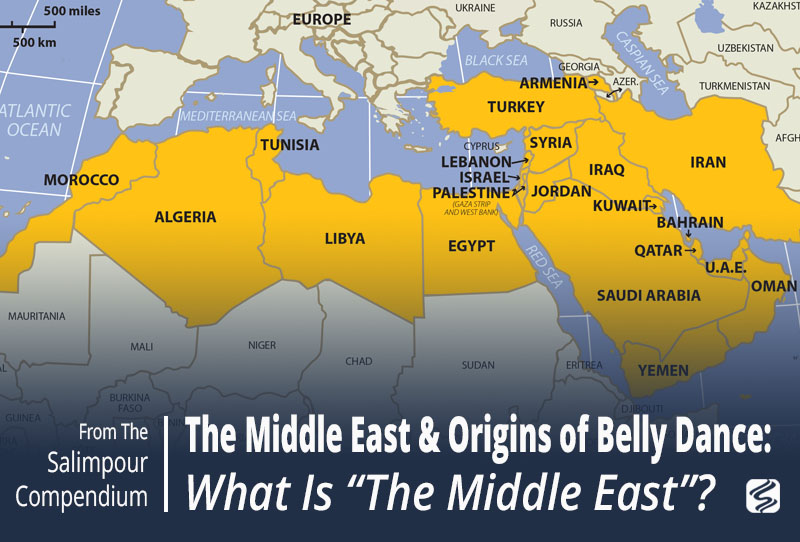

Before we can examine the subjects and histories that Jamila explored and introduced in her articles, we must introduce and understand several topics. The first, of course, being “The Middle East,” the region from which our dance has come.¹

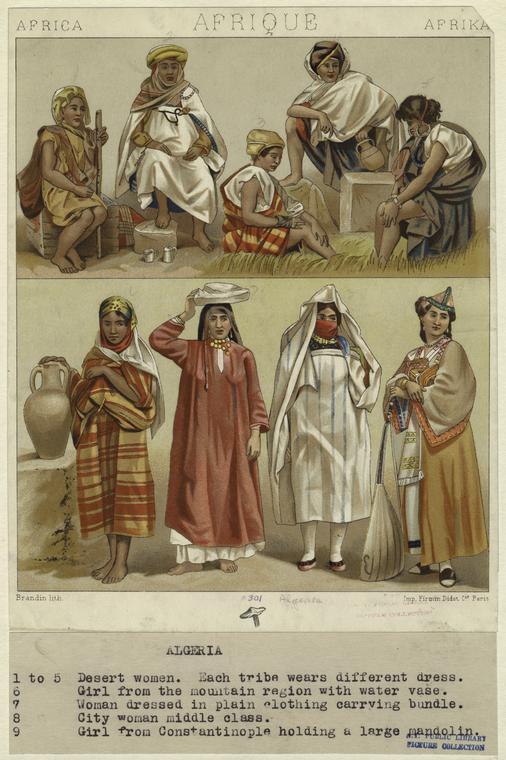

The Middle East (from a European and American perspective) is a region that encompasses southwestern Asia and northern Africa. In some contexts, the term has recently been expanded in usage to sometimes include Afghanistan and Pakistan, the Caucasus and Central Asia, and North Africa. It’s often used as a synonym for Near East, as opposed to the Far East; however, since the early 1900s, the term “Near East” has fallen out of favor except in select academic contexts. The corresponding adjective is Middle Eastern and the derived noun is Middle Easterner. The term itself is inherently Eurocentric; for Europeans, the area is the middle of what is east, but for the rest of the world, the directional reference is inaccurate. That said, the term “Middle East” has become used globally, even used by those in the region, who refer to it by its Arabic term, ash-sharq al-‘awsaṭ, which literally means “the Middle East.” We continue to use the term “Middle East” simply because there is no nother term that adequately describes this region of the world. Some scholars will, however, refer to the region as Middle East/North Africa, and abbreviate it as MENA. Other terms used to describe certain areas within the region include “Arab World,” but it excludes Turkey and Iran. The term “Islamic World” is too broad, as it would include the Muslim-majority countries in South and Southeast Asia. For the sake of this study guide, we will be using the term “Middle East” to describe the Arab states, Turkey, Iran, and North Africa, and this volume focuses mainly on the Islamic history of these states, as it more directly affects us as belly dancers than does the region’s rich ancient and pre-Islamic history. In addition, in keeping in the spirit of Jamila’s writing and time, we also use the now somewhat antiquated term “Oriental.”

The modern political Middle East as we understand it today began after World War I, when the Ottoman Empire, which was allied with the defeated Central Powers (which also included the German and Austria-Hungarian Empires), was partitioned into a number of separate nations. Other defining events in this transformation included the establishment of Israel in 1948 and the departure of European powers, notably Great Britain and France. We will explore this transformation later in this chapter.

Ethnicities and Languages

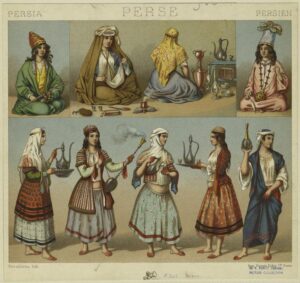

The Middle East, as defined for this survey, is home mostly to Arabs—remembering, of course, that not all Arabs are Muslim and not all Muslims are Arab—however, it is home to many other ethnic groups, including Turks, Persians, Jews, Kurds, Assyrian/Chaldean/Syriacs, Armenians, Azeris, Circassians, Greeks, and Georgians. The three most spoken languages, in terms of sheer numbers of speakers, are Arabic, Persian, and Turkish, representing Afro-Asiatic, Indo-European, and Turkic language families respectively. Various other languages are also spoken in the Middle East.

Arabic—a Semitic member of the Afro-Asiatic languages—is the most widely spoken language in the Middle East, being official in all of the Arab countries. It is also spoken in some adjacent areas in neighboring Middle Eastern non-Arab countries. The second-most widely spoken language is Persian—an Indo-Iranian language in the Indo-European family—mostly in Iran and some border areas of neighboring countries. It is much influenced by Arabic (through Islam) and Aramaic (the pre-Arabic lingua franca of the Middle East). The third-most widely spoken language, Turkish, is mostly confined to Turkey, one of the region’s largest and most populous countries; Turkish is a Turkic language and has its origins in Central Asia. Other languages spoken in the region include Syriac (a form of Aramaic), Armenian, Azerbaijani, Berber, Circassian, smaller Iranian languages, Hebrew, Kurdish, smaller Turkic languages, and Greek.

What is Islam?

We’ll first begin with a (very) brief introduction to Islam. In the interest of brevity, we are unable to address many of the complex theological concepts inherent to a thorough study of a religion and its followers.

Islam is a monotheistic faith with many ties and traditions rooted in Judaism and Christianity. According to Muslim tradition, Islam began on the Arabian Peninsula (in what is now Saudi Arabia) with Abraham, who, according to Muslim belief—together with his son Ishmael—built the Ka’aba² in Mecca, the shrine to which millions of Muslims make pilgrimage. Scholars classify Islam as an Abrahamic religion, as are both Judaism and Christianity.

The central figure of Islam is Muḥammad ibn ’Abdullāh, who was born around 570/571 CE in Mecca and was the founder of the religion of Islam. Muslims regard him as a messenger and prophet of God (Arabic: Allah), the last law-bearer in a series of Islamic prophets, and, by most Muslims, as the last prophet as taught by the Qur’an (the Muslim holy book) in Sura (Chapter) 33:40–40. Muslims consider him the restorer of an uncorrupted original monotheistic faith of Adam, Noah, Abraham, Moses, Jesus, and other prophets. He was also a diplomat, merchant, philosopher, orator, legislator, reformer, military general, and, according to Muslim belief, an agent of divine action. However, unlike the Christian belief that Jesus Christ himself was divine and the son of God, Muslims do not believe that Muḥammad was divine (or any of the other prophets, for that matter). They do believe, however, that Muḥammad was the last of God’s messengers, just as Jesus, Moses, and Abraham were also messengers of God. For Muslims, Islam is a sort of “Abrahamic Monotheism, Version 3.0.” The word “Islam” comes from the Arabic linguistic root S-L-M, and means “submission;” other words from this root include salām (peace) and “Muslim” (one who submits to the will of God).³

According to Muslim history, the Archangel Jibrīl (Gabriel) delivered the first of the revelations to Muḥammad in 610 CE, that being to “recite” a message from God. Muḥammad continued to receive revelations for the remaining 22 years of his life. According to Islamic tradition, Muḥammad was already 40 years old when he had his transformational religious experience and became a prophet and political leader. As with the early Christian church, the number of his followers grew by word of mouth, and by 615 Muḥammad had a steady flow of believers. This alienated some of the more powerful members of his own Quraysh tribe, who were polytheists, and some of his followers were forced to flee. Muḥammad negotiated with the nearby town of Yathrib (which later became known as Medina, or “City of the Prophet”) and took refuge there in 622. This event is known as the hijra, and it is the date on which the Islamic calendar begins. Muḥammad established himself in Medina as the secular, military, and religious leader of the new Islamic community, or ‘umma.

According to Muslims, the words revealed to Muḥammad are the actual speech of God transmitted to the Prophet by the angel Jibrīl. These words became the Qur’an, which Muḥammad’s companions memorized, recited, and wrote after every revelation dictated by Muḥammad. Most of Muḥammad’s tens of thousands of companions learned the Qur’an by memory and repeatedly recited in front of Muḥammad for his approval or the approval of other companions. Muslim tradition agrees that although the Qur’an was authentically memorized completely by tens of thousands verbally, the Qur’an was established textually into a single book form shortly after Muḥammad’s death in 633 CE by order of the first Caliph Abu Bakr at the suggestion of his future successor ‘Umar. Muslims also consider the original Arabic verbal text to be the final revelation of God. For the disparate peoples of the Arabian peninsula, who were at the time of Muḥammad’s revelation mostly pagan and had no written codes of law, the Qur‘an as revealed to Muḥammad provided a greater sense of order, cohesion, and identity. In addition to the Qur‘an are the Ḥadīth—the recorded sayings of the Prophet not included in the Qu’rān—and the Sunna, which are the examples of living given by Muḥammad.

Islam spread from the Arabian Peninsula to the surrounding lands as the Arab nomads raided their non-Muslim neighbors, bringing a new religious message to pagan, Christian, and Jewish peoples. Historian Christopher Catherwood notes that the revelations in the Qur’an were not just for Muḥammad and his descendants, but for anyone who would listen, regardless of their familial or ethnic origins.⁴ Unlike Christianity, Islam was never a persecuted faith, allowing it to become a political and military power in the hands of Muḥammad’s successors. Between 633 CE and 750 CE, Islam had spread through north Africa and into the Iberian Peninsula to the west, into what is now eastern Turkey and the Caucasus to the north, and to Persia and Central Asia to the east. By the 13th century, its followers had spread it to India and Southeast Asia.

Today one-fifth of the world’s population identifies themselves as Muslim and a follower of Islam. Of course, Islam as a religion is not monolithic, and there are many interpretations of the Qur’an, Ḥadīth, and Sunna, just as there are of the Christian Bible. We must also remember that many Arabs identify as Christian, specifically as followers of the Coptic (mostly in Egypt), Greek Orthodox, Roman Catholic, and Maronite (mostly in Lebanon) churches.

Shi‘a and Sunni

Jamila mentions in her article that Suhaila’s Persian grandmother was “determined” to train Suhaila as a “good Persian girl,” and that she dressed young Suhaila in a chador and taught her to recite verses of the Qur’an. Suhaila’s Persian family was Shi‘a, like most Iranian Muslims. Shi‘a Muslims are the minority amongst the global Muslim population; however, in Iran, Shi‘a Muslims are the majority. The division between Sunni and Shi‘a has caused great strife as each group holds different beliefs over whom should lead the ‘umma. This division can be traced back to the death of the Islamic Prophet Muḥammad.

Muḥammad had no sons, only a daughter, Fatima, who married his (and her) cousin, ‘Ali. Some scholars of early Islamic history argue that the standard Arab practice at the time was for the prominent men of a kinship group, or tribe, to gather after a leader’s death and elect a leader from amongst themselves. At the time of Muḥammad’s death, there was no specified procedure for the shura (consultation) on this issue. Candidates were usually, but not necessarily, from the same lineage as the deceased leader, and capable men who would lead well were preferred over an ineffectual heir. As Muḥammad had no male heirs, no one could succeed him by blood as leader of the new Islamic community, and he had not laid out any plans for who should lead the ‘umma after his passing. This lack of guidance permanently divided his followers.

After Muḥammad’s death, four men, known as caliphs (Arabic: khilāfa, meaning “succession”)—Abu Bakr, ‘Umar, ‘Uthman, and ‘Ali—succeeded him, respectively, as all had been related to the Prophet by marriage or blood. These caliphs are known in Sunni Islam as the Rashidūn, or “rightly guided ones.”

Sunni Muslims—about 85% of Muslims, named after the Sunna—believe that the community chose Muḥammad’s father-in-law Abu Bakr, and that this was the proper procedure of succession. Sunnis further argue that a caliph should be chosen by election or community consensus.

However, Shi‘a Muslims disagree. They believe that the indications Muḥammad had given that his chosen successor was ‘Ali ibn Abi Tālib, his cousin and son-in-law, take precedence over any decision by shura. According to the Shi‘a point of view, ‘Alī and his descendants were the only proper Muslim leaders or imāms, and he should have replaced Muḥammad as caliph and that caliphs were to assume authority through genetic lineage. Today, most scholars agree that of the global population who identify themselves as Muslim, 15% of them are Shi‘a.

In addition to Sunnis and Shi‘a, there is a little-known third branch of Islam, the Ibadi Kharijites, who believe that the caliphate rightly belongs to the greatest spiritual leader among Muslims, regardless of his lineage. Their sect is quite small and found mainly in Oman.⁵

Arabic—a Semitic member of the Afro-Asiatic languages—is the most widely spoken language in the Middle East, being official in all of the Arab countries. It is also spoken in some adjacent areas in neighboring Middle Eastern non-Arab countries. The second-most widely spoken language is Persian—an Indo-Iranian language in the Indo-European family—mostly in Iran and some border areas of neighboring countries. It is much influenced by Arabic (through Islam) and Aramaic (the pre-Arabic lingua franca of the Middle East). The third-most widely spoken language, Turkish, is mostly confined to Turkey, one of the region’s largest and most populous countries; Turkish is a Turkic language and has its origins in Central Asia. Other languages spoken in the region include Syriac (a form of Aramaic), Armenian, Azerbaijani, Berber, Circassian, smaller Iranian languages, Hebrew, Kurdish, smaller Turkic languages, and Greek.

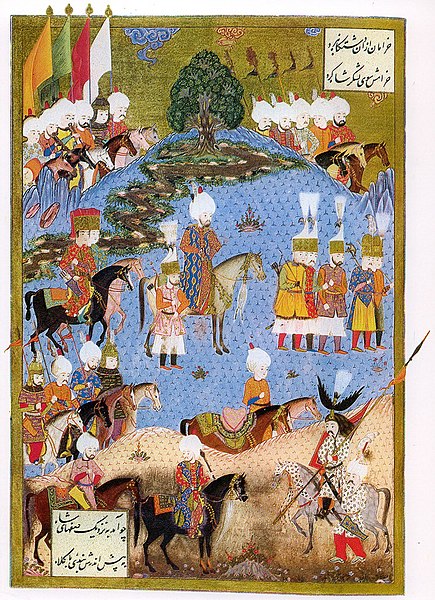

The Ottoman Empire

Much of the historical elements of this study guide have their roots in the Ottoman Empire and its legacy. At the height of its power, in the 16th and 17th centuries, the empire spanned three continents, controlling much of southeastern Europe, western Asia, and North Africa. It was at the center of interactions between the Eastern and Western worlds for six centuries. The Ottoman Empire also contained 29 provinces and numerous vassal states, some of which were later absorbed into the empire, while others were granted various types of autonomy during the course of centuries; Egypt was one of those states in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Because of its rule over so many different peoples, particularly at its height, Ottoman rulers, and sultans, insisted on loyalty to Islam as a prerequisite for employment in the court, regardless of ethnicity. The Ottoman Empire lasted from July 27, 1299, to October 29, 1923.

The Ottoman Empire was named after its late-13th century ruler Osman who in a battle against Byzantine forces in 1301 established himself and his people as a new and powerful player amongst the Turkic groups that inhabited the Anatolian peninsula. In the 1350s, the Ottomans began their conquest of the Balkans, which was almost totally under their control by 1389 when the Ottomans defeated a Serbian army at Kosovo. In 1453, Mehmet II (known as Mehmet the Conquerer, naturally) captured Constantinople (now modern-day Istanbul), which the medieval Umayyad and Abbasid caliphs and even the fierce Mongols were unable to wrench away from the fading Byzantine Empire. This conquest signaled the official end of the last remnants of Rome and the Byzantine Empire, and Mehmet established the capital of his empire there. In 1517, the Ottomans under Sultan Selim captured the nominal Abbasid Caliphate of Mamluk-controlled Egypt, as well as the Muslim holy cities of Mecca and Medina on the Arabian Peninsula.

Despite being unable to capture the Austrian city of Vienna in 1529 (they tried again in 1683, and failed again, but not without first introducing coffee), the Ottomans, under Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent (ruled 1520 to 1566), did capture most of Hungary, further encroaching upon European territories. In 1534 Suleiman was able to capture Mesopotamia from the encroaching Safavid regime (a Shi‘a Persian regime whose founder was also of Turkic descent), who conceded defeat in 1555. By the 1550s, the Ottomans ruled from the Iranian border to northern Africa, and from Southern Egypt to the Austrian frontier.

By the 16th century, the empire faced political challenges from which it was never able to fully recover. Ottoman attempts to capture Vienna and parts of Russia resulted in a series of military defeats by Austrian and Russian forces. Later, the occupation of Egypt by French emperor Napoleon Bonaparte and the British in the late 18th century eroded Ottoman control in North Africa. In the 19th century, the empire became too geographically large for direct control, and an indirect rule was established, with each vilayat, or state, becoming semi-autonomous. By the end of the 19th century, the Ottoman Empire had declined due to internal conflict and European colonialism. The Ottoman Empire came to an end, as a regime under an imperial monarchy, on November 1, 1922.

Partitioning of the Ottoman Empire (1918 – 1922)

The Arab states, unlike Turkey, did not become immediately independent after the decline and fall of the Ottoman Empire. After World War I, the large number of territories and peoples formerly ruled by the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire was divided into several new nations.

Under the then-secret Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916, and without the consent of the peoples living in these areas, the remnants of the Ottoman territories were divided between France, which was given the northern areas (what is now Syria and Lebanon), and the United Kingdom, which was given the southern areas (what is now Iraq, Jordan, and Israel/Palestinian Territories). The United Kingdom and France later decided the borders of the current countries in these regions. The agreement is seen by many as a turning point in Western-Arab relations. It negated T. E. Lawrence’s (often romanticized) promises to the Arabs for a national Arab homeland in the area of Greater Syria in exchange for their siding with the British forces against the falling Ottoman Empire, which left many Arabs feeling betrayed by and bitter towards the United Kingdom. The remaining parts of the Ottoman Empire on the Arabian Peninsula became parts of what are today Saudi Arabia and Yemen.⁶

Modern-day Turkey

The Ottoman decision to support Germany in World War I meant the empire shared the Central Powers’ defeat, which led directly to the overthrow of the Ottomans by Turkish nationalists led by Mustafa Kemal, who became known to his people as Atatürk, meaning “Father of the Turks.” Atatürk is credited with successfully renegotiating the Treaty of Sèvres (1920) which ended Ottoman/Turkish involvement in World War I and with establishing the modern Republic of Turkey, which the Allies officially recognized in the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923, which also formally ended the Ottoman Empire as a political entity. As Turkey’s first president, Atatürk implemented an ambitious program of modernization that emphasized economic development and secularization, using western European nations as models. He effectively transformed Turkish culture to reflect European style laws and clothing, adopted Hindu-Arabic numerals, the Roman alphabet, separated the religious establishment from the state,⁷ and granted women the right to vote.

Egypt after World War I

In 1914, as a result of the declaration of war with the Ottoman Empire, of which Egypt was nominally a part, Britain declared a Protectorate over Egypt. In December 1921, the British authorities in Cairo imposed martial law, and in 1922 the British installed King Fuad as ruler, who died in 1936. King Farouk (full name Farouk bin Ahmed Fuad bin Ismail bin Ibrahim bin Muḥammad Ali bin Ibrahim Agha) inherited the throne at the age of sixteen, and when alarmed by Italy’s invasion of Ethiopia, signed the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty, requiring Britain to withdraw all troops from Egypt, except at the Suez Canal (which the British agreed to leave by 1949). During World War II, British troops used Egypt as a base for Allied operations throughout the region. British troops withdrew to the Suez Canal area in 1947, but nationalist, anti-British, and anti-colonial feelings continued to grow after the war.

Between July 22-26, 1952, Lieutenant General Muḥammad Naguib led a group of disaffected army officers, known as the Free Officers, and overthrew King Farouk, whom the military blamed for Egypt’s poor performance in the 1948 war with Israel (often referred to in the Arab world as “The Disaster”). Following a brief experiment with civilian rule, the Free Officers repealed the constitution and declared Egypt a republic on June 18, 1953. Colonel Gamal Abdel Nasser, the first authentically Egyptian ruler of Egypt since ancient times, became president and evolved into a charismatic leader, not only of Egypt but of the Arab world. His presidency ushered in a movement known today as Arab nationalism, which aimed to unify Arabs across the Middle East, regardless of religion, against colonial Western powers and influence.

When the United States and the World Bank withdrew their offer to help finance the Aswan High Dam in mid-1956, Nasser nationalized the Suez Canal and appropriated the canal’s valuable revenues to Egypt. The crisis that followed, exacerbated by growing tensions with Israel over guerrilla attacks from Gaza and Israeli reprisals, support for the Algerian war of liberation against the French, and against Britain’s presence in the Arab world, resulted in the invasion of Egypt in October by France, Britain, and Israel.

In 1958 Egypt joined with the Republic of Syria to form a short-lived state called the United Arab Republic (UAR). It existed until Syria’s secession in 1961, although Egypt continued to be known as the UAR until 1971. Nasser was perceived throughout the Arab world as the man who had humiliated the imperialist powers, and he became a hero to millions of Arabs.⁸ After Nasser’s death in 1970, another of the original Free Officers, Vice President Anwar Sadat, was elected President of Egypt. In 1971, Sadat established a treaty of friendship with the Soviet Union but, a year later, ordered his Soviet advisers to leave. In 1973, Sadat launched the Yom Kippur War (October War) with Israel. Following the Sinai Disengagement Agreements of 1974 and 1975, Sadat created a fresh opening for progress by his dramatic visit to Jerusalem in November 1977. This led to the invitation from President Jimmy Carter of the United States to President Sadat and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin to enter trilateral negotiations at Camp David, which resulted in the historic Camp David Accords, signed by Egypt and Israel and witnessed by the US on September 17, 1978. The accords led to the March 26 1979, signing of the Egypt–Israel Peace Treaty, by which Egypt regained control of the Sinai in May 1982. On October 6, 1981, Islamic extremists—some of whom would later form the group al-Qa‘ida—assassinated President Sadat. Hosni Mubarak, Vice President since 1975 and commander of the Egyptian Air Force during the October 1973 war, was elected President later that month. Mubarak ruled Egypt until the Egyptian revolution in 2011 when he resigned.

The content from this post is excerpted from The Salimpour School of Belly Dance Compendium. Volume 1: Beyond Jamila’s Articles. published by Suhaila International in 2015. This Compendium is an introduction to several topics raised in Jamila’s Article Book.

If you would like to make a citation for this article, we suggest the following format: Keyes, A. (2023). What is “the Middle East”? Salimpour School. Retrieved insert retrieval date, from https://suhaila.com/what-is-middle-east

¹ For thorough introductions to the Middle East and its people, see Christopher Catherwood’s very accessible A Brief History of the Middle East (London: Constable & Robinson, 2011); Adam J. Silverstein’s lively Islamic History: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), and Albert Hourani’s classic, A History of the Arab Peoples (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2010).

² The Ka’aba is the cube-shaped shrine at the center of Islam’s most holy mosque, Al-Masjid al-Harām.

³ Words in Arabic, along with other Semitic languages, are created around three (sometimes two or four) letter roots. The meaning of the word changes according to the auxiliary letters used with that root.

⁴ Catherwood, A Brief History, 79.

⁵ For greater detail on the birth of Islam, see Hourani, Silverstein, and The Oxford History of Islam edited by John L. Esposito (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999).

⁶ For an in-depth look at the personalities and powers behind the partitioning of the Middle East, see David Fromkin, A Peace to End All Peace (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1989).

⁷ Although Turkey is a secular nation, it regulates its Imāms (religious leaders) by requiring them to be monitored and sanctioned by the state. Its legal system, however, is separate from Islamic law and operates independently from religious institutions.

⁸ Catherwood, A Brief History, 200.