After their marriage, Ardeshir immediately threatened to break both of Jamila’s legs if she danced again or even took a step into her own club. His sudden change in attitude upset Jamila. He knew that she had been married twice before, had worked in the circus, and that she was a belly dancer. Even though he now seemed embarrassed by her, he seemed quite willing to accept the money she made as a partner in the Bagdad. Jamila began to feel that the only reasons Ardeshir married her were to get his green card and to receive the regular income she received as a club owner. Jamila sold her share of the club to Yousef, asking only for the exact amount she initially contributed with no interest. Yousef paid her in cash, and Jamila presented it to Ardeshir. Ardeshir was livid that she went behind his back to sell her part of the Bagdad.

Without her income from the Bagdad—both as owner and performer—teaching dance became Jamila’s only other means of earning an income. She held classes in her and Ardeshir’s apartment on Telegraph Avenue in Berkeley.¹ She turned the living room into a studio for dance instruction and costume making.

Ardeshir wanted to avoid being drafted into the US Army, so he insisted on having children immediately.² Jamila was pregnant within three months of marriage, and Ardeshir was “sure” they were having a boy. He called the child Amir and anxiously awaited the birth of his son. In the meantime, Jamila continued teaching through most of her pregnancy.

When Jamila gave birth to a girl, Ardeshir was greatly disappointed. He told Jamila to name the girl whatever she wanted. At first, Jamila suggested Zenouba, but he did not approve of what he considered an Arabic name. Jamila then suggested the name Suhaila (“little star” in Farsi),³ and Ardeshir acquiesced.

Just after Suhaila was born, Ardeshir made a tape recording in Farsi and sent it to his family in Iran: “Most respected Father and Mother. I am sorry to have to bring you such sad news. My wife has given birth to a baby girl. I apologize for having disappointed you. Please forgive me, and remember that I am young and strong and will go on to produce many sons. God will surely give me another chance to honor my family.”

After Suhaila was born, the new family moved to San Pablo, a city less politically charged than downtown Berkeley, which since the mid-1960s has been a center of political protest and tension, such as riots spurred by the Free Speech, anti-Vietnam war protests, and civil rights movements in the mid- and late-1960s. Ardeshir worked at a restaurant and bar, first as a dishwasher, then as bartender. He demanded that Jamila get a “respectful” job, which for him meant not teaching dance.

Jamila eventually found a position working at a bank within walking distance of their home. Within a month, the bank discovered she had fabricated her qualifications and fired her. Ardeshir then allowed Jamila to return to teaching with the dictate that she do so discreetly.

Jamila based payment for her group classes on the “honor system;” she set out a jar, and students paid $2.50 for each class. She also taught private lessons. Ardeshir required that she give his father all her earnings. Ardeshir was slowly bringing over his Persian family, the first of which were his parents and younger male cousins. In the 1960s, the Iranian Army sometimes drafted teenage boys as early as age 14, and the Salimpour family wanted to bring them to the US to avoid their conscription. After the club where Ardeshir worked promoted him to the position of manager, he and Jamila rented a two-bedroom home in El Cerrito so that more of his family could live with them.

Suhaila was severely pigeon-toed, a condition inherited from her father’s family. When she began to walk she would trip over her feet. Children were very cruel and would make fun of her. I tried everything, including metal rods with special shoes. Nothing seemed to work. As a last resort, I put her in ballet classes three times per week. The first position (turnout) exercises corrected the defect after a few years. Little did I know that it was a blessing in disguise. Not only did her posture improve, but also it gave Suhaila a bodyline to become characteristic in the new style of Middle Eastern dance.

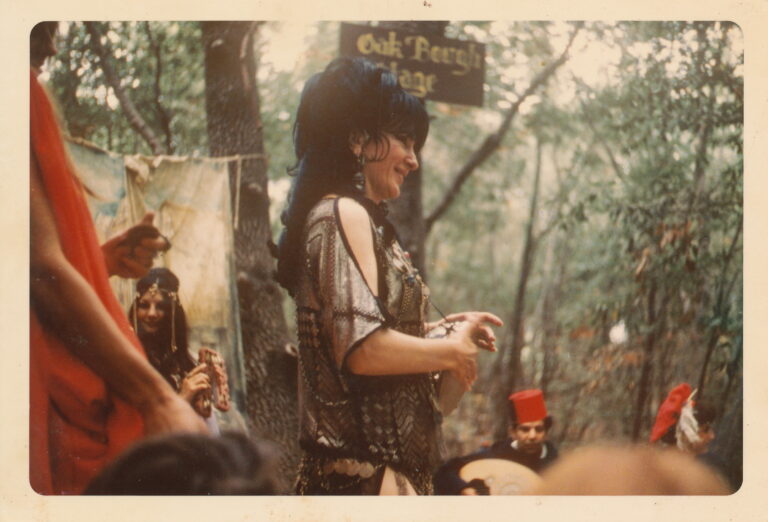

In 1968, Jamila’s Bal Anat first debuted at the Northern California Renaissance Pleasure Faire featuring folkloric and fantasy dancers, with the authentic displayed right alongside hokum. Jamila was a cabaret dancer who had learned from and been inspired by the great classic dancers of Egypt’s Golden Era. She applied her same technique to the Bal Anat troupe but with different stylization and costuming to different music to achieve a different sentiment. The combination of Jamila’s dance format technique and the unique Bal Anat presentation began the tribal movement and stylization that would soon take root in the belly dance community.

First we had to have a name. After much thought I settled on Bal Anat, which was originally spelled Baal Anat after the Phoenician God and Goddess, but then I changed Baal to Bal, which in several languages means dance. So it became Bal Anat, dance of the Mother Goddess, Anat.

We had to have a banner, as that was customary for clans, tribes, and families represented at the Renaissance Faire. It took very little time to decide on the Hand of Fatima as our symbol. I bought colored cardboard, and cut out a hand and background in several colors until I came up with what I thought was the right combination. I decided our logo, “Naught but truth,” would be in the ancient pre-Islamic language called Tifinagh, and my name was written in Cuneiform.⁴ And then I picked up the Yellow Pages to find someone to actually make it. What did I know about making a banner? Well, when I heard the price quotes, I became an instant banner-maker.

Suhaila’s Early Renaissance Faire Memories

I remember getting ready to attend the Renaissance Faire with my mother. We would sit at the table for breakfast with the family. I patiently waited for my mother to give me a subtle nod as a sign that we were ready to excuse ourselves to the basement. Everyone in the family knew what we were preparing to do, but they acted oblivious. By not acknowledging it, they could pretend. With one overhead light bulb and a mirror the size of a postcard, mom would get both herself and me ready. We would then leave for the faire in mom’s red Volkswagen Beetle. I felt like we were escaping to what I wanted to be my real life, and being at the Renaissance Faire was truly the only time I was happy during those early years when we shared a house with my father’s family. One of my earliest memories was of traveling down the highway with the windows open, the rumble of the car engine, and my mother’s coins tinkling in the wind. When we returned home, we could quietly enter through the basement and remove all traces of make-up and costuming to integrate back into the family as if we’d been there all along.

In the earliest photos of Bal Anat at the Renaissance Pleasure Faire, some of the dancers wore chiffons and prints. Jamila gravitated toward a specific ethnic look and was one of the first to start collecting assuit and Bedouin jewelry. She scoured garage sales and antique stores to match images in National Geographic. She wanted to be authentic, and she costumed most of the members. In fact, she gifted many of the original and most valuable pieces to her students. She gave her famous belt buckle to John Compton who wore it throughout his career. Many of her students were gifted with assuit pieces and coin jewelry that Jamila crafted herself.

Country Joe’s “Jamila” Lyrics:

She’s one of the Eastern ladies,

The hand of Fatima protects her.

She is a living Shiva, hell of belly-dancer.

Her body is hanging the silver rings

And when she’s moving you can hear them ring.

She moves her hips and she moves her hands.

Her finger cymbals start to play with her now.

La la la la, la la la la.

She’s one of the Eastern ladies,

You can feel her charisma.

She is a living Shiva, hell of belly-dancer.

Slowly she moves and then faster and faster.

You must move quickly if you want to catch her.

The beat of the dumbek, the sound of the oud.

You can understand life when you see her move.

La la la, hey, la la la, hey!

In the first years of Bal Anat, Jamila did not yet have her own studio. She rented studio space in San Francisco for the group to practice performing. It was in that space that Jamila often ran into Jimi Hendrix and, on occasion, Janis Joplin, rehearsing.⁵ Jamila had several discussions with Jimi Hendrix. He loved the look of Bal Anat costuming, and Jamila agreed to make some body jewelry for him. Unfortunately, he died in September 1970 before she was finished. Jamila also met Joseph “Country Joe” McDonald (of Country Joe and the Fish) whose wife, Robin, was her student. Jamila and Joe became friends, and Suhaila has fond memories of visiting his home and playing in the yard with his daughter, Seven. Country Joe McDonald even wrote a song about Jamila titled, unsurprisingly, “Jamila.”

During this time, Ardeshir’s health was intermittent. When Suhaila was a baby, he was involved in a car accident; afterward, he began suffering serious side effects including dizziness and blurred vision. He was diagnosed with an inoperable brain tumor when Suhaila was three years old (sometime around 1969).⁶

Ardeshir’s family felt that his choice of wife brought disgrace upon the family, and they were concerned that Jamila would be entitled to family assets (including the anticipated settlement from his car accident) when Ardeshir passed away. His mother pressured him to separate from (with a goal to eventually divorce) Jamila, but Jamila was adamant about staying married.

In 1972, in an effort to handle the situation, Ardeshir mortgaged a house with a small down payment in Kensington, an unincorporated town just north of Berkeley. Jamila and Suhaila were moved first. Jamila was very concerned about splitting up the family and did not want to move without them, but she acquiesced when she felt adequately assured that Ardeshir and his family would soon follow. After a few weeks passed, Jamila realized that her husband and his family were not going to join her in this home. In fact, not long after Jamila and Suhaila moved, Ardeshir and his family bought and moved to a large home in Concord using the finalized settlement from his car accident.

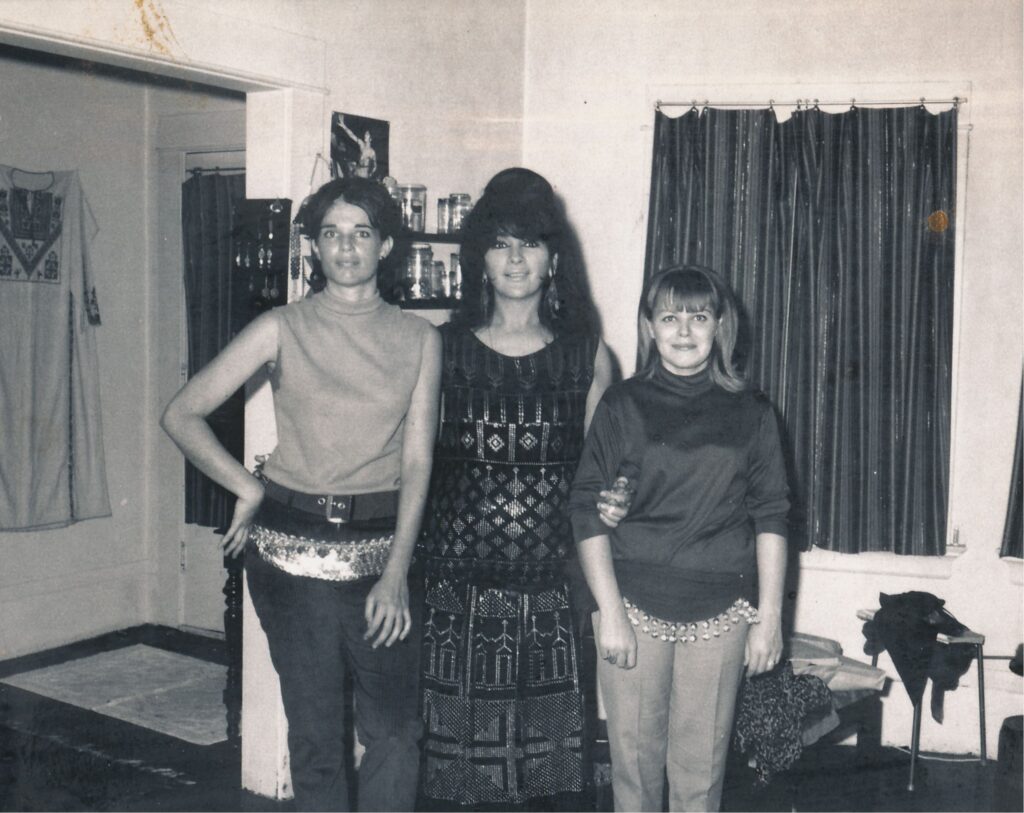

Jamila continued teaching in several locations in the area. After Suhaila was born, she taught at a folk dance studio on South Van Ness Avenue in San Francisco. Jamila observed that in the folk dance classes, students moved in a circle around the room, which inspired Jamila to do the same. She successfully structured her own classes so that dancers would travel in a counterclockwise circle around the studio.

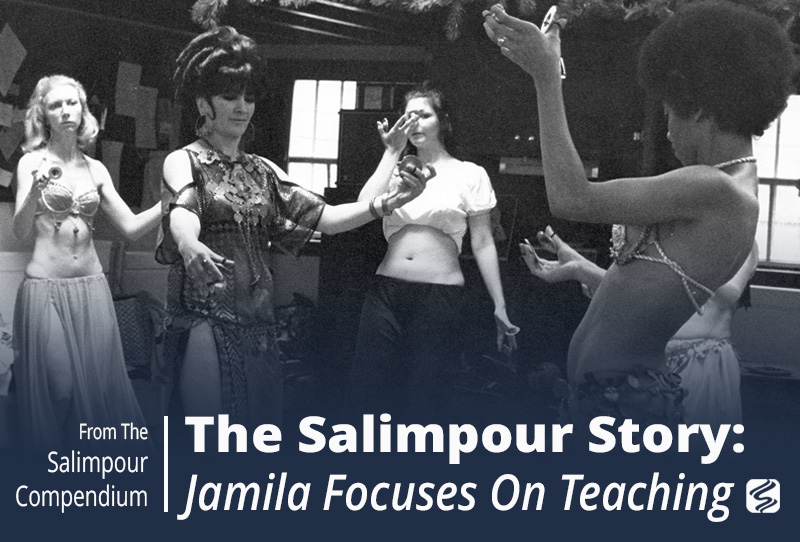

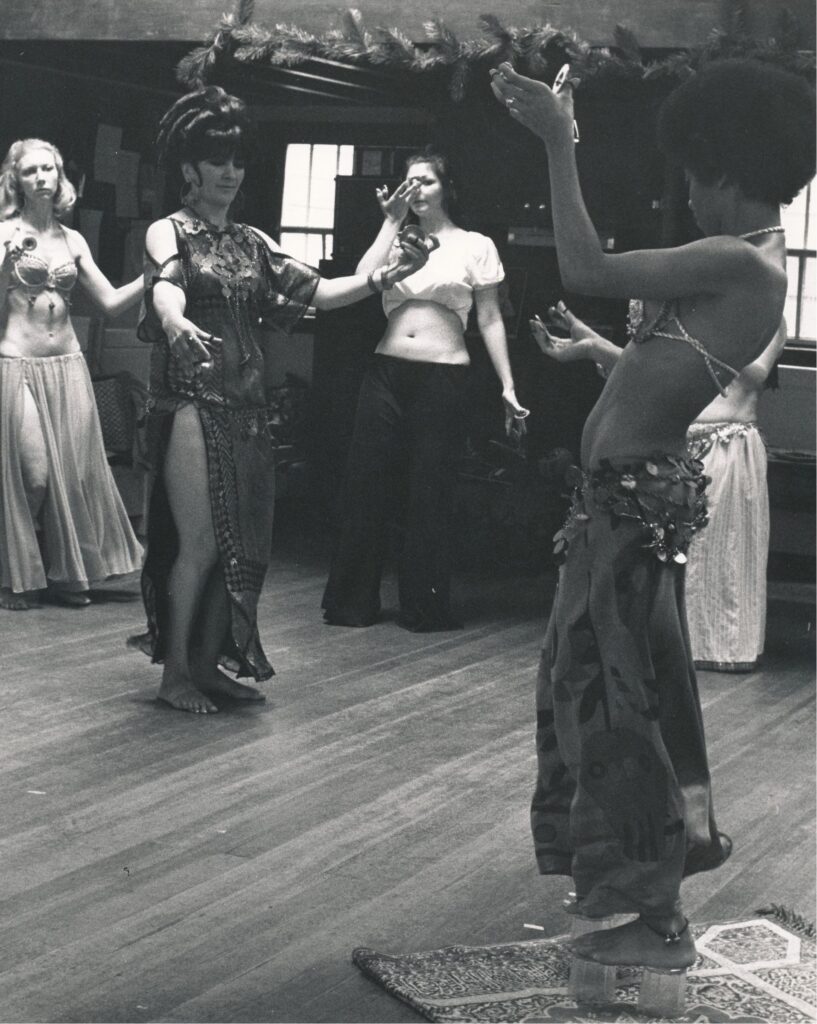

In addition to other temporary locations, Jamila taught at the Poultry Factory⁷ on the north end of Sansome Street in San Francisco. Suhaila remembers the large cement building as being industrial and cold. Jamila taught in full costume for a more “authentic” appearance: stage make-up, beehive hair, traditional Bedouin dresses, assuit, and other folkloric clothing.

After class, Jamila welcomed her students to sit and talk, which she called Circle Time. She began by lecturing about the dance and her experiences. Then she opened the discussion for her students. Many of the students lived a hippie lifestyle, of which their parents openly disapproved; some had run away from home, cutting off contact with their families. During Circle Time, they told uplifting, but often horrific, stories of their lives. The students felt comfortable talking to her. She was the same age as the mothers of many of her students, and she found that many of the young people were seeking a maternal connection they couldn’t find at home.

Now that they were living away from Ardeshir and his family, the new house became a sanctuary for Jamila and Suhaila. They began to feel free after having lived with a large and religiously devout family for several years.⁸ It was common for three or four of Jamila’s students to stay overnight. In fact, students were in and out of the house all day. If a student needed a place to stay for a short while, Jamila housed them. She was very devoted to helping her students, giving them guidance, teaching them to groom, and helping them find employment. When they needed it, she clothed, fed, and looked after them.⁹

Jamila wanted to create a place for her students to obtain performance experience as she had done for them at Sinbad’s Lounge in Los Angeles. Fadil Shahin, a former employee and musician at the Bagdad, bought a failing restaurant located two doors down from the Bagdad on Broadway Street and converted it into another Middle Eastern-themed club, the Casbah, which opened in 1969. Jamila stayed connected with Fadil so her advanced students to have a place to work and perform.

My student nights at the Bagdad, and its neighbor competitor the Casbah, evolved into my Moon Celebrations. I stopped using the term “student night” entirely after realizing that club owners would tempt novices into performing free with the promise of future employment, often jeopardizing the livelihood of currently working dancers. I often told my students not to mention they were students when they went to an audition. This way, if they felt ready and could pull it off, they wouldn’t have to fight the student stigma. Of course, I’d hoped they were ready to perform but many a student wanted to perform, ready or not.

Suhaila remembers going to these Moon Celebrations (also called Energy Celebrations) at the Casbah with her mother in the early 1970s, and she remembers the waitresses wearing I Dream of Jeannie-styled costumes. The nights would run late, and Suhaila usually had school the next day. When the show was over, Jamila and Suhaila would lie down on the booths to sleep. They would get up in the morning so Jamila could drive Suhaila to school from the club.

Jamila also tried to guide her students in costuming and etiquette. In the 1960s, strip clubs opened alongside the Middle Eastern clubs in North Beach. Customers in the area could distinguish between the types of performers as each costume type had “a look;” the belly dancers typically wore coin-decorated costumes, and the exotic dancers wore beaded costumes. Jamila felt it was important to keep the two distinguished from one another so there was no misunderstanding about which kind of dancer was performing at which kind of club. Although Jamila no longer danced in the clubs, many of her students did, and many of them were quite young. Jamila wanted to address the situation that was specific to North Beach. She emphasized a difference in costuming, but sometimes she felt the students didn’t understand. She then simplified her instruction, telling her students: wear coins, not beads. Later, Jamila discovered that some of her former students claimed she had said that belly dancers never wear beads, but that was certainly not the impression she meant to leave. In fact, in the early 1980s, when she costumed Suhaila in beads and even mixed beads and coins, some dancers criticized Jamila’s apparent hypocrisy without understanding the underlying reason for her early guidance.

Jamila continued lecturing on and demonstrating Oriental dance throughout the San Francisco Bay Area, something she had done since the 1960s, with repeat engagements at universities as well as elementary, middle, and high schools. She often brought along Bal Anat and other students with her to feature various cultural elements of the dance mentioned in her presentations. At the time, during the first major heyday of belly dance, it was not unusual for her class series at universities and theaters to have over 100 students in the room.

At the urging of his mother, Ardeshir finally divorced Jamila in 1975. In the divorce settlement, Jamila received full title for her existing Kensington home and child support to help cover the mortgage and utilities, but she gave up any claim to the greater family holdings.

Jamila opened her own dance studio at 471 Broadway in San Francisco in 1976 on the same block as the Bagdad and the Casbah, separated by only one building, one floor above a strip club called the Woofer, which had formerly been the Jazz Workshop.

The property’s previous renters used it as a pornography theater and left it in need of serious renovation. One of Jamila’s students, now known as Aida Al Adawi, had received a modest inheritance from her grandmother and gave it to Jamila to help fund converting the space into a dance studio. Suhaila accompanied her mother to the studio and worked the front desk of her mother’s classes.¹⁰ The unit’s bathroom upstairs rarely worked; Suhaila remembers having to go downstairs to the Woofer to the bathroom. The bouncer let her through quickly, shielding her from seeing the activity there.¹¹

In 1976, Ardeshir’s health worsened. Even though they lived separately for several years and were officially divorced, Jamila still visited him almost daily at the hospital. In his last days, she rarely left his side. He died on May 23, 1976, at the age of 34, six years beyond the doctors’ original prognosis.

The content from this post is excerpted from The Salimpour School of Belly Dance Compendium. Volume 1: Beyond Jamila’s Articles. published by Suhaila International in 2015. This Compendium is an introduction to several topics raised in Jamila’s Article Book.

If you would like to make a citation for this article, we suggest the following format: Totten, V. (2023). Salimpour Story. Jamila Focuses on Teaching. Salimpour School. Retrieved insert retrieval date, from https://suhaila.com/the-salimpour-story-jamila-focuses-primarily-on-teaching

¹ Mario Savio (1942-1996), a leader of the newly formed Free Speech Movement, lived above the couple in the apartment complex. Like Jamila, he was a first generation American born in New York City to a Sicilian parent.

² From 1948-75, the U.S. Selective Service System provided sorting categories for local draft boards to sort and determine which young men (ages 18-25) were eligible for military service. Men with children could often get assigned Class 3-A: registrant deferred by reason of extreme hardship to dependents. As the U.S. participation in the Vietnam War increased in 1965, more young men were being drafted.

³ In both Farsi and Arabic, the name Suhaila refers to the Canopus star, which is considered the second brightest star in the night sky, the first being Sirius. Suhaila is often translated as “little star” meaning the smaller of the two brightest stars.

⁴ Tifinagh is a script used by the some Berber speaking tribes in North Africa from approximately the 3rd century BCE through 3rd century CE. Cuneiform is an early form of writing from Sumer and was used from approximately the 34th century BCE through 2nd century CE.

⁵ Jimi Hendrix (Johnny Allen Hendrix, 1942-1970) was an American musician and is considered one of the most influential and talented rock guitarists. Janis Lyn Joplin (1943-1970) was an American singer and songwriter known as the Queen of Psychedelic Soul. Both Jimi and Janis were part of the hippie counterculture movement, performed at Woodstock in 1969, and died of drug overdoses in 1970.

⁶ When he was younger and still living in Iran, Ardeshir made extra money with a game of strength when he went out drinking. He bet that he could withstand a Karate-style chop to the back of this neck—where his tumor later formed—without falling down. It was speculated that the tumor formed due to this earlier activity, but the car accident either initiated or escalated the development of severe symptoms. He fell into comas for days at a time and often needed the assistance of a cane or walker. He sought alternative therapies, but nothing improved his condition.

⁷ The Poultry Factory was a long-standing nickname given to a building which originally housed the California Poultry Company (1375 Sansome Street, SF), but was later converted for use by artists and teachers. Suhaila, who accompanied her mother to the classes there, remembers an artist in the building who owned a friendly black dog named Flea.

⁸ See “Customs, Conflicts, and Casualties”, Jamila’s Article Book, 2013, p34-6.

⁹ In 1977, Jamila Salimpour learned that John Compton, a former student, was in a coma in a San Francisco hospital after a motor vehicle accident. She went to the hospital every day to watch after him, and the staff assumed she was his mother. She also assisted in finding him legal representation.

¹⁰ Suhaila remembers the sounds of Broadway Street, especially the barkers who were encouraging people to enter the various clubs. On Saturdays evenings after class, they ate at Enrico’s (504 Broadway) across the street; the owner, Enrico Banducci, also owned the hungry i. On special occasions, they would eat at Vanessi’s (438 Broadway) which, when it opened in 1936, was one of the first restaurants in which customers could sit at the counter and watch the cooks prepare their food.

¹¹ One day, Jamila and Suhaila saw a huge nude photo of one of her students in a window of a strip club near the studio. Suhaila asked her mother, “Why is there a naked photo of one of the [Bal Anat] Karshilama dancers in that window?” Apparently, a few years earlier, the young woman allowed her then-boyfriend to take nude photos of her, although the photos revealed little. The ex-boyfriend sold the photos to the club; despite having legal assistance, the young woman was unable to get her photo removed from the strip club window. Suhaila said the corner of Broadway and Columbus was a demarcation line; beyond that block was a seedier area, and Jamila forbade Suhaila from ever leaving the “safe zone.”