Habibi: Vol. 8, Nos. 2&9; Vol. 9, No. 2 (1984-5)

The Disreputable and Irresistible Danse Orientale

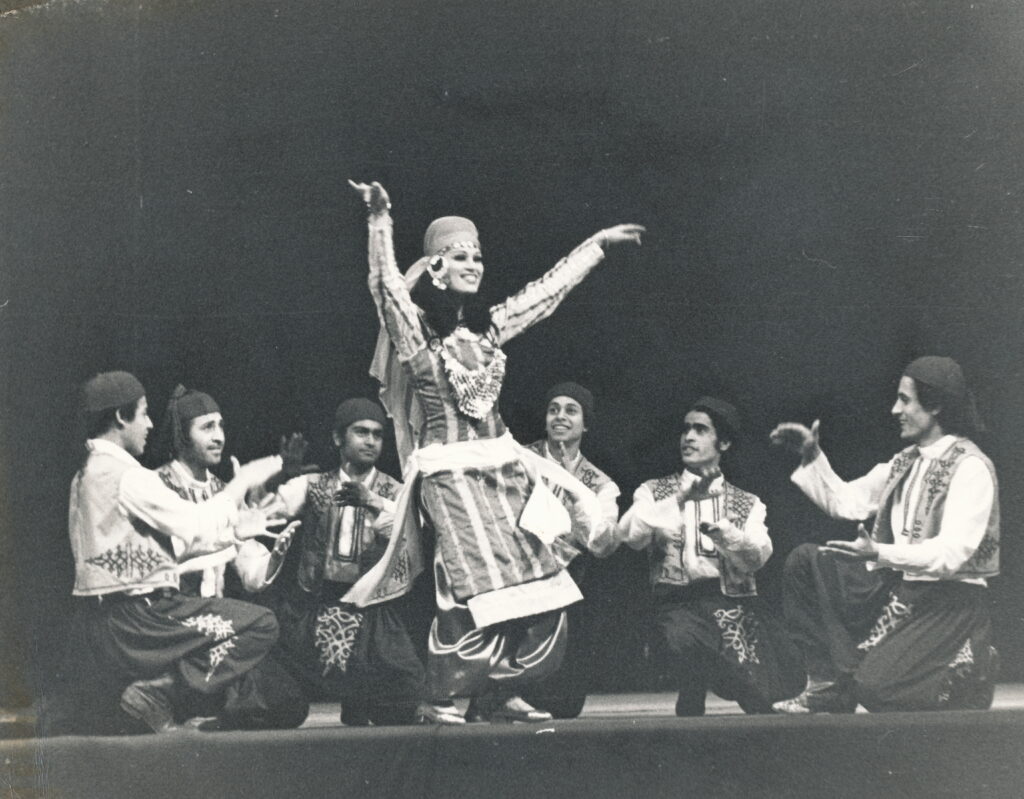

In the turmoil that followed the clash between the Russian ballerinas and the Egyptian cabaret dancers in the 1950s, the Egyptian government encouraged and financed folk troupes whose cautious choreography emphasized a modern technique drawn from folk material. Many of their movements were related to traditional oriental dance, although many observers concluded that the talented dancers projected a respectable, native Egyptian dance that was not to be associated with the disreputable danse orientale. The public acceptance of these troupes encouraged students and professionals to participate.

Simultaneously, cabaret dancers were told to cover up and tone down the “sexual” elements in their dance. Although they were required to be covered from their shoulders to their ankles, most simply added a body stocking from bra to girdle. The Egyptian government monitored cabaret dancers, their performance permits were sometimes withdrawn if they made gestures or allowed a drummer to leave his seat to follow them around the dance floor.

In the 1960s, a new school of cabaret dancers was emerging under the tutelage of the ballet masters. At this time, Sonia Ivanova, who was born in Russia and received her ballet training in England, was one of the leading ballet teachers in Cairo. Her students included the legendary Hoda Shams Eddin who was considered one of the better oriental dancers of that era.

Egyptian Folklore Dance

I first heard the term “folklore” associated with the Reda Troupe, and after that with the National Folkloric Company of Egypt. When some of the members migrated to North America, it was the first time American dancers were shown Egyptian-choreographed dances based on the movements of the Egyptian people.

Egyptian folklore dance has stimulated the imagination of many artistic and creative Egyptians. For the first time in the history of Egypt, educated people have become involved in researching and preserving the folk arts, and have succeeded in presenting them to a broader and sometimes more conservative audience than ever before. Many who had training with these prominent troupes went on to become choreographers and chorus dancers with the top dance shows that featured the greats of oriental dance.

Also, artists such as Nahed Sabry, who have not had folklore background, have obviously been influenced by it, resulting in the inclusion of a variety of movements inspired by folklore. Aside from the “typical” oriental movements, arms and body lines are given greater attention resulting in an overall look that is more graceful.

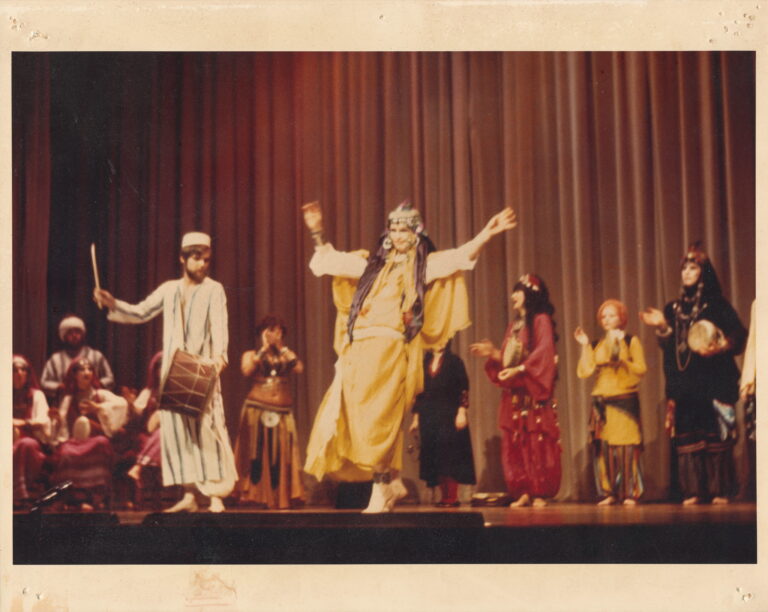

When folklore troupes were still in their infancy, creative minds at the heads of their troupes envisioned stylized dance choreographies based on provincial folk festivals and customs. As certain members of the troupes became skilled enough in dance and documentation, they were sent out in the field to study, observe, and record, to bring back to the troupe any pertinent information as to the dance and customs of the people. The findings were clarified, codified, and put into a choreographed form in preparation for performance. An enormous dance vocabulary was to become available from the dances of Egypt. Never before had dances such as the zar, dervish, tahtib, and Ghawazee (to name but a few) been written down to be presented for all time.

It is through video that we can see choreographer and National Folkloric Troupe member Muhammed Khalil performing a theatrical tahtib, backed by a line of male dancers. In another dance, he is a fisherman who “hooks” a pretty female fish and they perform a storytelling version of the “Bambudiyah” together. Mohammed Khalil pretends to play the rebaba, accompanying several female dancers who perform a group baladi number, followed by a female soloist who performs a raqs al-khayl (horse dance). Through the miracle of video, we can collect, select, and judge for ourselves the talents that appeal to us the most.

For thousands of years, Egyptian culture has kept its customs and traditions which have come down to us today through folk dances based on everyday life activities. In 1975, in honor of the American Centennial, Egypt sent a folk troupe that delighted audiences from coast to coast. This was the first large group of entertainers to come to the United States since the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893. Many members of that group are now based in Cairo, Egypt, and are the chosen native entertainers of the Samer Theatre for the Folk Arts. This organization is sponsored and supported by the Ministry of Culture of Egypt and is directed by Abdel Rahman El Shafe’I, one of Egypt’s leading young theatre directors. About two years ago they were brought to the United States again where they made several appearances on the East Coast. The program included a zeffa wedding procession, zar and tannoura dancing, tahtib, oriental dance, Nubian and Arab folk songs and dances, and tableaux.

In the folklore troupes, several lead dancers branched out and formed troupes of their own, still patterned after the parent troupe. By the second and third troupe generations, many of the folkloric dancers were now choreographing for some of the top cabaret dancers. The marriage of folkloric and cabaret was taking place.

What makes it so interesting is that while the folk dance troupes were being formed and encouraged by the Egyptian government, the popular cabaret dancers were never included in folkloric shows. The ever-popular, but controversial and sometimes embarrassing, danse orientale was left out; the intellectual and academic backgrounds of the newly acquired chorus boys and girls were played up, while their pelvic movements were de-emphasized. The folkloric troupes might include in one of their shows a “safe” version of oriental dance by one of their members but never did they “feature” one of the current popular artists such as Nadia Gamal, Naima Akef, Sohair Zaki, or Nagwa Fouad.

Nadia Gamal eventually went to Lebanon to work in movies and supper clubs and was a featured dancer in the Ba’albek Festival, but her background was comparatively similar to the training of the lead folkloric dancers, that is, heavy on ballet discipline for total body training. Nadia Gamal also choreographed many of the folk dance styles from Lebanon into her own performances, thus popularizing their dances. So, at the height of the popularity of the folk troupes, the style and approach to oriental dance differed between the folkloric approach and the popular cabaret approach. Today they are beginning to merge.

What strikes me most about folklore style is the extensive use of body locks combined with clean and precise pelvic movements. Also, the dance steps and combinations must really fit the passages of the music. There is very little repetition of steps. The time had come, too, when certain folklore dancers who were gifted in choreography were sought out and highly paid for their creativity.

Today, a wealth of dance steps has become available to practitioners of the danse orientale. Because of the complicated musical compositions, today’s dancers must have a larger dance vocabulary with which to express the passages of the music. When I first started dancing, the music and the dance were much simpler. Today a dancer must be able to show her creative and interpretive skills with each new piece of music to which she dances. She must also have a solid foundation in the “old style” so as not to lose the “oriental” feeling if it is to come across as Egyptian at all.

The Choreographers of Cairo

The former folk troupe lead dancers are now choreographing for the “top” oriental dancers of Egypt. The dances differ in that they are more of a showcase for the dancer’s total skill. The complex musical compositions have varying moods and tempos. Ideally, today’s top Egyptian dancers have their music written especially for them, such as such as “Raqs Sohair Zaki” or “Raqs Mona” (for Mona Said). As individual as the music is, so the dance must be new and creative, still keeping with the Egyptian soul of the dance. Sometimes when we see a great dancer, we eventually hear of another creative force behind that dancer, and in most cases it is a folklore dancer turned choreographer.

As we become aware of the latest approach to Egyptian choreography, let us take a look at some of the people who are responsible for the exciting innovations in the Egyptian dance vocabulary of today. When we review the dance vocabulary of “old time” dancers, we see its limitations when applied to the new and innovative musical compositions. Egyptian dance vocabulary is growing and extremely challenging.

For example, Mohammed Khalil was a lead dancer and soloist with the National Folkloric Company of Egypt. From having been in that environment, dancing, creating new moves and body lines, it is almost natural that he should have continued to pass on his training and knowledge to other artists. Mohammed Khalil brings a classical approach to the cabaret dancer in his interpretation of the “modern Egyptian musical.” Several years ago Hani Mehanna was commissioned to compose new music for Nagwa Fouad, and Muhammed Khalil was selected to create the choreography. The now famous piece we have come to know as “Aroussa” has a beautiful melody, but is more complex than the folk tunes which many dancers use. It is the type of musical that a dancer must know “cold” to respond to the changes. One must watch Nagwa Fouad’s performance of Khalil’s choreography to “Aroussa” many times to see the many facets in its choreographic interpretation. I can only say that I appreciate it more every time I see it. “Aroussa” is now several years old and only fairly recently has been imported to the United States via video, An Evening with Oriental Dance. Nagwa Fouad’s dance is a display of skill and training. When she has finished “Aroussa”, she repeats her audience-pleasing drum solo in which she shimmies while isolating shoulder locks and other combinations for which she has become famous. Her performance ends in baladi solo accompanied by a mizmar with herself on zagat. She removes these and picks up a cane for a short solo and finale.

Raqia Hassan also choreographed some of the beautiful and lyrical dances for Mona al-Said. What beauty, calmness, and control! And it is so different from Mohammed Khalil! The music was especially written for Ms El Said, a practice which has become very widespread among the top dancers. Unfortunately, the cost of hiring a composer and choreographer is prohibitive to all but the wealthiest of dancers. Word has it that the cost of choreography and music can run into the thousands of dollars.

We have selected and collected special Egyptian pieces to choreograph for some time. Now styles and techniques can be readily analyzed, especially through videos. Many dancers are utilizing that medium to great advantage. Suhaila choreographed “Joumana” in 1982. It is interesting for us to see someone else’s interpretation of the same piece. We recently acquired a video in which an Egyptian dancer interpreted “Layali al-Lubnani,” a complicated piece by Mohammed Abdel Wahab. Suhaila and I choreographed that in 1978. Our new piece called “Hayati” was performed by Nahed Sabri. Ours is a totally different approach, and the comparison we find very interesting. So far we have about thirty-two choreographies, all totally different. What makes choreography so wonderful is that the music is different, and so the dance is and should be different. Every time you see the dancer you see something completely new.

Conclusion

Although it has been a lengthy courtship, and the political pressure has been off the cabaret dancer for many years now, the marriage between folkloric and cabaret is still ongoing. In the past thirty years, many up-and-coming dance stars have looked consistently graceful through years of training in classical dance forms. Gone are the days when a dancer’s repertoire is limited to the repetition of a few steps. Each dance is as different as each new musical composition. The direction is individuality both in compositions and choreographic delivery. Nowadays the music is written especially for a dancer. She commissions, she approves, she pays. Sometimes a dancer will use her composition for a long time. This usually means that she developed a routine, becoming her own choreography. Now we watch for that “total” look where arms are graceful, spins balanced, and bodies poised. I look for a truly oriental body language that has developed into a sophisticated oriental dance vocabulary.

This article was published in Jamila’s Article Book: Selections of Jamila Salimpour’s Articles Published in Habibi Magazine, 1974-1988, published by Suhaila International in 2013. This Article Book excerpt is an edited version of what originally appeared in Habibi: Vol. 8, Nos. 2&9; Vol. 9, No. 2 (1984-5).