Habibi: Vol. 4 No. 3 (1977); Vol. 5; Nos 5&6 (1979)

He was at that time performing in Las Vegas and had invented the male-female partner dance that was to be copied by many after seeing him. He was charming and humble—too humble. I took my necklace off—a Kabyle silver Hand of Fatima with talismans suspended from the fingers, which I loved and wore for good luck— and put it around his neck to protect him and his genius.

I can’t remember the year…I was working at the Bagdad Cabaret in San Francisco; I had just come out of the dressing room perspiring from my last show when I became aware that someone was on stage dancing, and the audience was in ecstasy. The dancer had created such a mood that the musicians were playing like I had never heard them playing for my shows, and I was caught up in the excitement. Who was this dancer thrilling the audience so soon after I thought I had wrung them out with my ten-minute shimmy solo? I heard gasps from the audience in response to the movements on the stage. Yousef Kouyoumdjian, the violinist-owner of the Bagdad Cabaret, was visibly moved by the dancer as he leaned forward to play from his oud through his violin. I stood transfixed in the middle of the club, numbed by the music, the dancers, and the emotion of the audience. I recall, now, how surprised I was to discover that the dancer was a young man.

He had a sash tied around his hips, and he was wearing a kind of white shirt without a tie and black cotton pants with regular shoes. He was playing finger cymbals to the syncopation of the music, and there was no doubt that he understood the music and the mood that it conveyed to him. He moved to the music, he was moved by the music, and the musicians were moved by him; the total involvement was so intense that the audience went wild. Entrance, taqsim, finale. The audience stood up applauding and would not sit down. Some customers came over to him as he left the stage with their cocktail napkins in their hands to ask for his autograph. They tugged at him, and the men in the audience came over to him to congratulate him. I was in that crowd and, as he wiped his forehead, I led him to a table. In awe of him, I kept asking him, “Who are you? Who are you?”

Ahmad’s dance style was what I had seen in the old Egyptian movies. He calls his style “the old Cairo tradition” and, indeed, from what I see that is coming out of Egypt these days, he is one of the few left who is truly an “old world dancer”. What was his upbringing? What were his inspirations? When did he decide to perform professionally? What, if any, were the obstacles which confronted a male dancer? I have always looked forward to the day when I could visit him on his home ground; we were to have long talks in his Montreal apartment which was crowded with memorabilia from his family and professional life.

Ahmad Russell Jarjour was born in Montreal, Quebec, to Nicholas and Iskander (translates into Alexandra) Jarjour. His mother came from a town called Rashaya El Wadi (formerly in Syria and now in South Lebanon). His father migrated from Mardin which was taken over by Eastern Turkey. They refer to themselves as Mesopotamians.

When the family started migrating to Montreal at the turn of the century, Ahmed’s grandfather rented a building which had three separate apartments. His mother was married there, and he was born there, sharing the building with about twenty aunts and uncles. In their leisure time, they would dance and dance and dance. Not that they had that much leisure. The living was hard and money had to be saved for the new arrivals. One of his uncles opened a grocery store that catered to Arabic menus. From the age of six Ahmad worked as a stock boy, filling twenty-five-pound bags with potatoes, bulgur, lentils, and all the exotic spices necessary for Arabian dishes. No other language but Arabic was spoken with customers or relatives. The neighborhood where Ahmad lives in Montreal is made up of predominantly Arabic-speaking peoples from the same country and towns as his relatives.

We would awake to the sounds of many tambourines played in a tempo that was suited to the strides of a wedding procession. The pieces are called Zaffah, and they were the most tranquilizing favorites of Ahmad Jarjour. The record player was turned on, and the needle was set in the familiar groove before he started the coffee. It was a familiar pattern for us the length of our stay in Montreal.

Our wake-up service was Nagat Ali, one of the last of the great Zaffah vocalists. Ahmad’s taste in music was the soothing old classical style and, as far as we were concerned, impeccable.

One can only consider his past and experiences an education if you are fortunate enough to be around him for any length of time. He was a collector of oriental memorabilia and the days of our visit were punctuated with “listen to this…come look at this…” We absorbed as much as we could but felt a deep frustration knowing that our visit was limited and our education would have to be cut short.

J: What did you call yourself that you say you only associated with the best?

A: I was a groupie; I was one groupie.

J: But you said that you were lucky enough to know the best!

A: I was lucky enough to know the best. You just don’t get to know everyone that you admire, but I was fortunate in that I was able to get to know some of the greatest performers I had seen in my very young years by following them around, by having them see me constantly. I was running after the singers for lyrics, I was running after the dancers for new steps. I was very young at the time, and I was tolerated. But I learned from these people; these were my roots.

J: Who were some of these people?

A: My earliest recollection isn’t of dance, although dancing was around me night and day. There was quite a famous man, you might have heard of him, named Taliah Baida. He sings mawwals and attaba. He sang all over the United States and Canada for the Syrian and Lebanese communities there. At that time they could not stage a large hafla [Arabic for “party”] (Middle Eastern festival) so they would make as large an evening as they could in their homes to invite this man over to sing. It was my first taste of sheer professionalism because he was a showman, and he was backed only with oud and tabla. He sang mawwal all night long, and it takes a hell of a good voice to keep seventy-five to a hundred people all seated together, enthralled for one entire evening. That was my first experience with anything professional. I was about six years old. I’ll never forget it. I can remember the room as it was…the people’s faces…and I subsequently bought a lot of 78 rpm recordings of him. He recorded a lot in Canada, and he died in Canada.

J: What was your next experience?

A: Well, what had preceded that wasn’t professional. We had a lot of music and dancing about the house every Sunday. That was the only day everybody was at home. We were a big family, we numbered over twenty people living in one large house. Upstairs lived my paternal grandparents and their eight children, and downstairs lived my maternal grandparents and their nine children. They all sang, danced, played, but, always on Sunday. But I didn’t have to wait for Sundays; you see, I was all alone in that house during the week with my youngest aunt to take care of me. We had stacks of ten inch 78 rpm records (very, very early Oum Khalthoum, Abdel Wahab and Farid al-Atrash, Asmahan) which I used to entertain myself all day long. I would listen to music all day long.

J: Did your aunt dance…the one that was taking care of you?

A: Yes, she did dance, but she didn’t teach me to dance. There is only one that cared enough to show me anything because it wasn’t necessary for a boy to learn to dance at that time, and at my age at that time and at that place. It was my Aunt Edna who taught me to play Arabic tunes on the piano; she taught me to dance, and it was she that I would sing long duets with on our family’s long drives into the country. She was also part of a singing group when she was in her teens called “Benat El Beled”. They recorded mostly folkloric. When Edna would go to a hafla they would save her until the last because at a hafla no one gets up to perform on their own accord. You have to be invited up on the floor to dance always by another woman who has been pushed on the floor. When she has finished her little number, she will approach you and she’ll do a little shoulder shimmy and she’ll bow; then she’ll straighten up and beckon to you with her hands to follow her to the floor. Once you get to center floor she will leave you, and they never do more than three minutes. They’re too modest to do anymore. The musicians were usually a local family, usually brothers.

I must tell you something while it is fresh in my mind. Middle Eastern men really don’t have many dances of their own; I’m talking of the Fertile Crescent. Debke is of course a man’s dance, but anything wavering from the standard debke is forbidden for a male. They have many expressions, and salty language to use when you do get up on the floor. But I was very young and could get away with it. When I was invited to dance I would always have to march up to my father and ask his permission first, “Daddy, can I dance?” He always said yes, but I had to observe protocol by asking him. If I had got on that floor without asking him, he would have dragged me off.

J: Well Ahmad, as a professional you achieved a status that very few men or women have. So, to begin at the beginning, you moved in with Fawzia Amir and became her devotee, a practice incidentally which is very old world.

A: I was lucky that I already had one foot in the door when I saw my first Egyptian dancer in films because I already knew how to dance, but I was seeing there on screen my first professional, my first glimpse of costumes. Then came Fawzia; I give a lot of credit to Fawzia Amir. She was the owner of the Club Sahara. She first began to dance in a club in Montreal called the El Morocco with her sister Amira Amir who has since passed away. Amira was a singer and a film actress but came to tour with her sister in an act.

J: What was the next thing that influenced your dance direction?

A: The start of Egyptian films coming to play in our community hall in Montreal. I couldn’t understand Egyptian Arabic at that time, and I couldn’t read the subtitles because I was too young, but I remembered everything that dancer did on screen and I took it home with me. They usually ran the films for three nights. If my grandparents took me on one night, I would ask a set of aunts or uncles the next night and beg them to take me to see the film one more time and, if I was lucky, I could maybe even get to see the film a third time. We didn’t get them often, but when they came I got to see all of them and I saw all the “name” dancers that are familiar to us. Some of them were impressive and some unknown.

J: Ahmad. . .what made you become so fascinated with oriental dance?

A: I wanted to dance. I had decided at age sixteen that I was going to be a male oriental dancer; I was going to do it as a male. Fawzia Amir did it to me. All at once she socked it to me. She was too much for me to take. When I met her, I made that decision that I just spoke of. I left school, I left my home and my family and I moved in with her. I became her “boy Friday.” I became her secretary, and her errand runner; I did everything just so that I could accompany her to work and watch her perform her three shows a night.

J: I’m trying to think about how the dance impressed me. I just thought it was one of the most beautiful things I had ever seen and I just wanted to imitate what I saw, never really thinking I could become professional. I thought that the dancers I saw were so lucky to be able to dance the oriental dance. It made me happy just to watch them and it made me happy to try to remember the steps I had seen in the films. I never thought I could achieve what I had seen because I thought that a lot of their body movements were a genetic response to a familiar cultural pattern, it was so appealing to me that I moved in with an Egyptian family. I wanted to be in that environment. In many ways, making the decision to become an oriental dancer resulted in many trials along the way because it wasn’t accepted. It was considered déclassé, especially twenty years ago.

A: Toward the end of this month will be twenty years since I had my first professional engagement.

This article was published in Jamila’s Article Book: Selections of Jamila Salimpour’s Articles Published in Habibi Magazine, 1974-1988, published by Suhaila International in 2013. This Article Book excerpt is an edited version of what originally appeared in Habibi: Vol. 4 No. 3 (1977); Vol. 5; Nos 5&6 (1979).

Photo Credits (From Jamila Salimpour Archives):

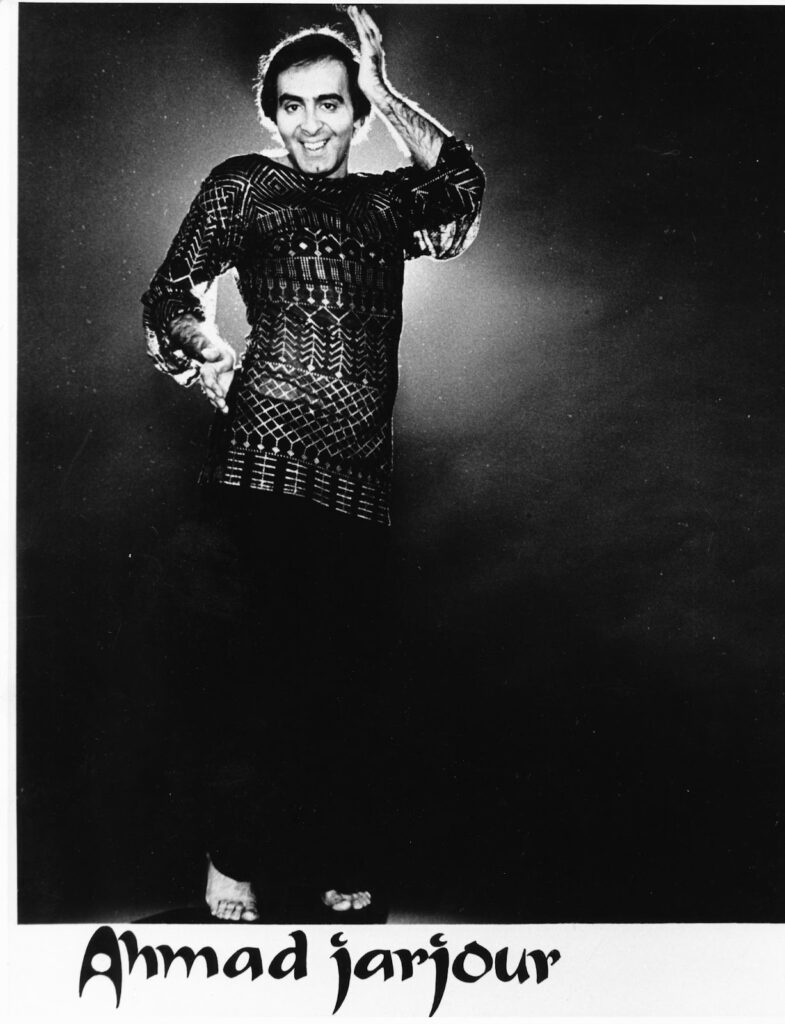

- Ahmad Jarjour promotion photo.

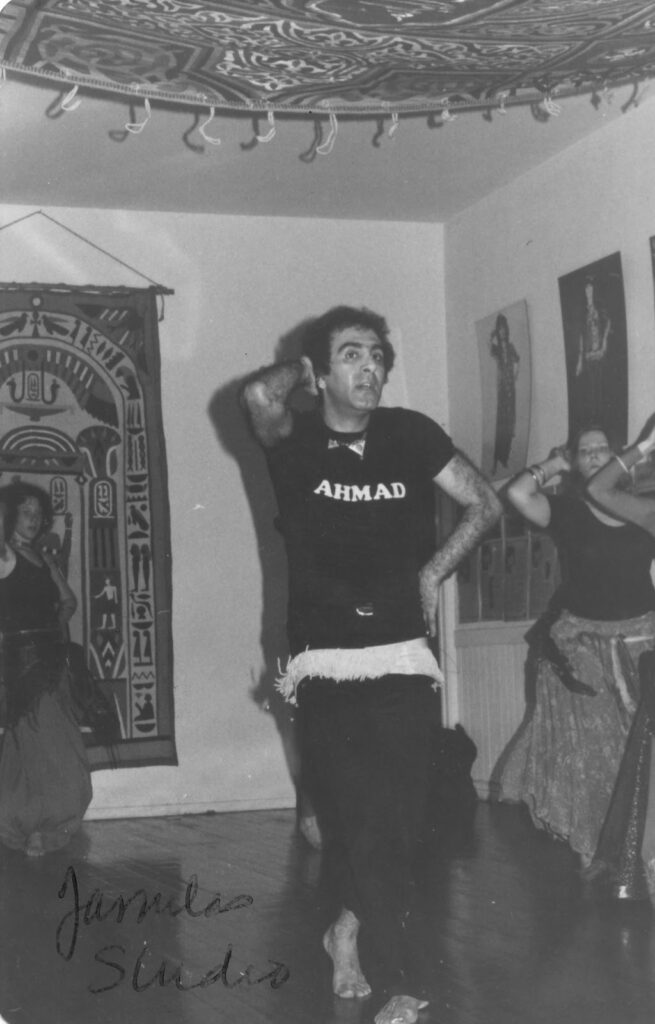

- Ahmad Jarjour in Jamila Salimpour’s dance studio.

- Ahmad Jarjour teaching in Jamila Salimpour’s dance studio.

- Ahmad Jarjour teaching in Jamila Salimpour’s dance studio.

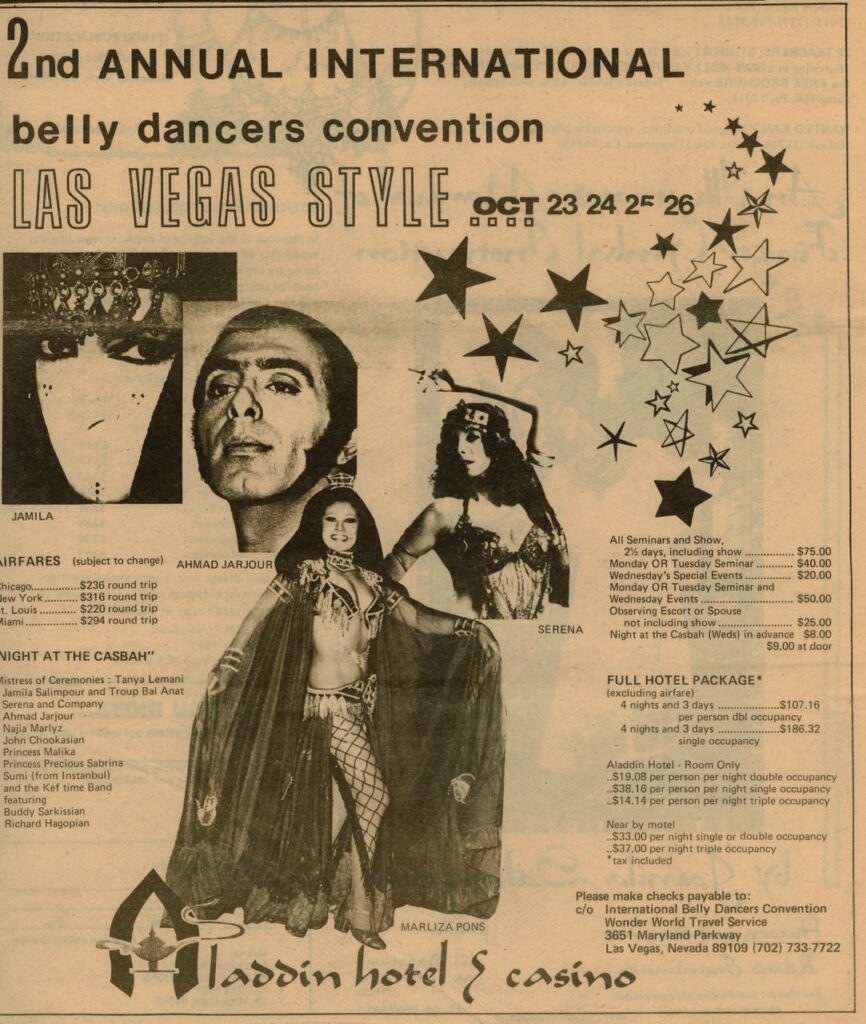

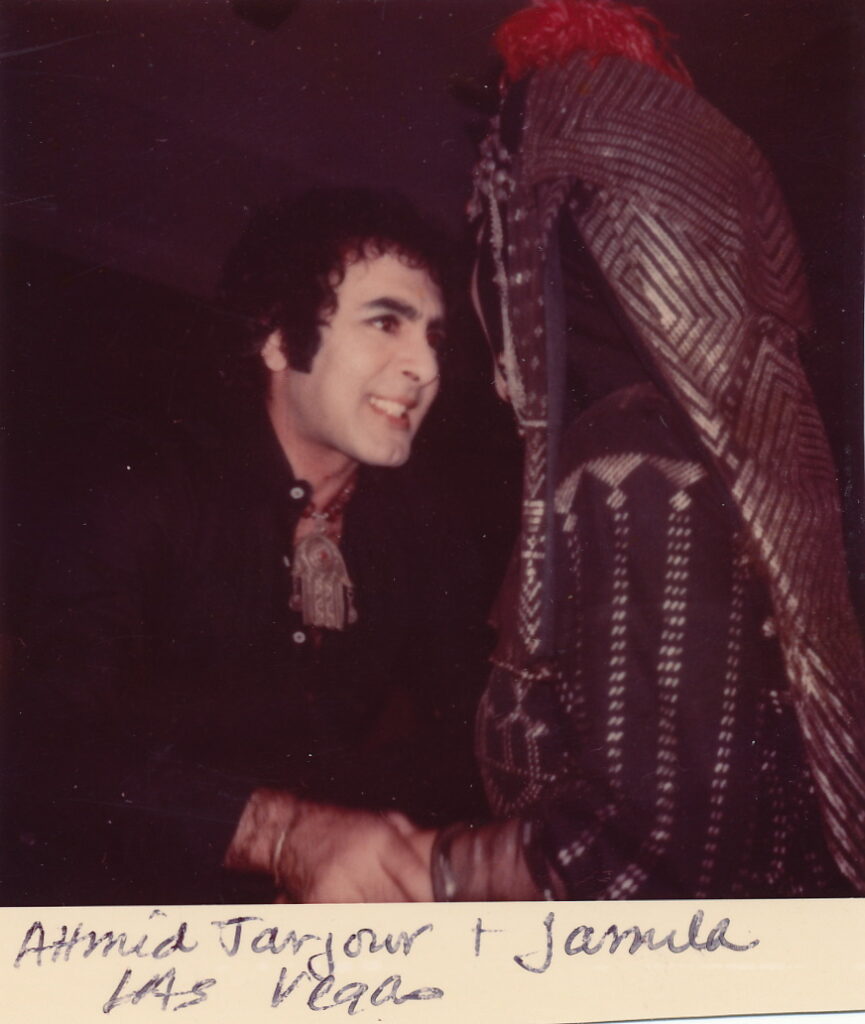

- Jamila Salimpour and Ahmad Jarjour performing at 2nd Annual International Belly Dancers Convention, Las Vegas.

- 2nd Annual International Belly Dancers Convention, Las Vegas, flier.

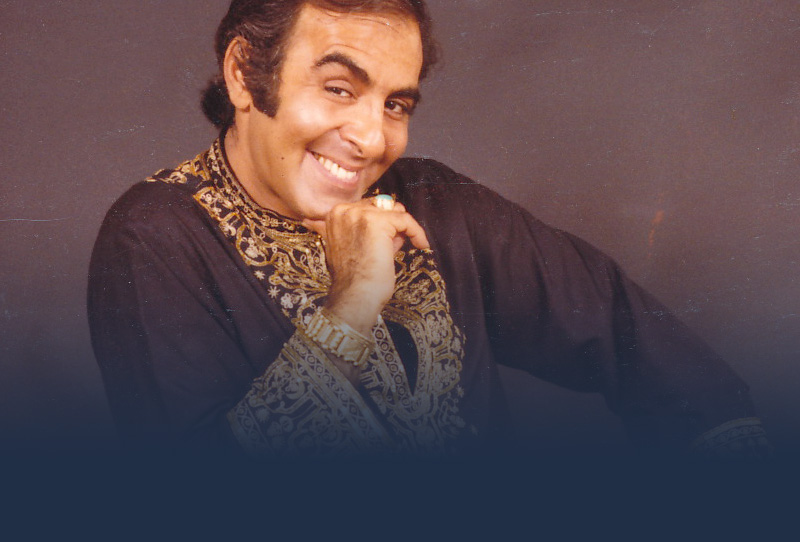

- Ahmad Jarjour promotion photo.

- Ahmad Jarjour and Jamila Salimpour at the 2nd Annual International Belly Dancers Convention, Las Vegas.