Habibi: Vol 5 No. 8 (1980)

Every now and then we come across an article or a book that expresses our thoughts so well that it seems that the author was clairvoyant and had somehow read our thoughts, answered our questions, and written them down. Such was the case with The Orientalists by Philippe Jullian, a book full of information about the artists who painted both the facts and fantasy of Oriental life from the 18th century up to the Victorian era. You will recognize many of the paintings and will be amazed at the number of artists with which we are as yet unfamiliar.

Orientalism dates from the moment artists began to dress their models in turbans and fluttering belts. Lucas van Leyden’s “Daughters of Lot” and the Bathshebas in the tapestries and miniatures at the end of the Fifteenth century were the first almehs (dancing girls) to be imported. The fall of Constantinople in 1453 brought the East deep into Europe. Very soon turbans, kaftans, and scimitars became familiar to Europeans.

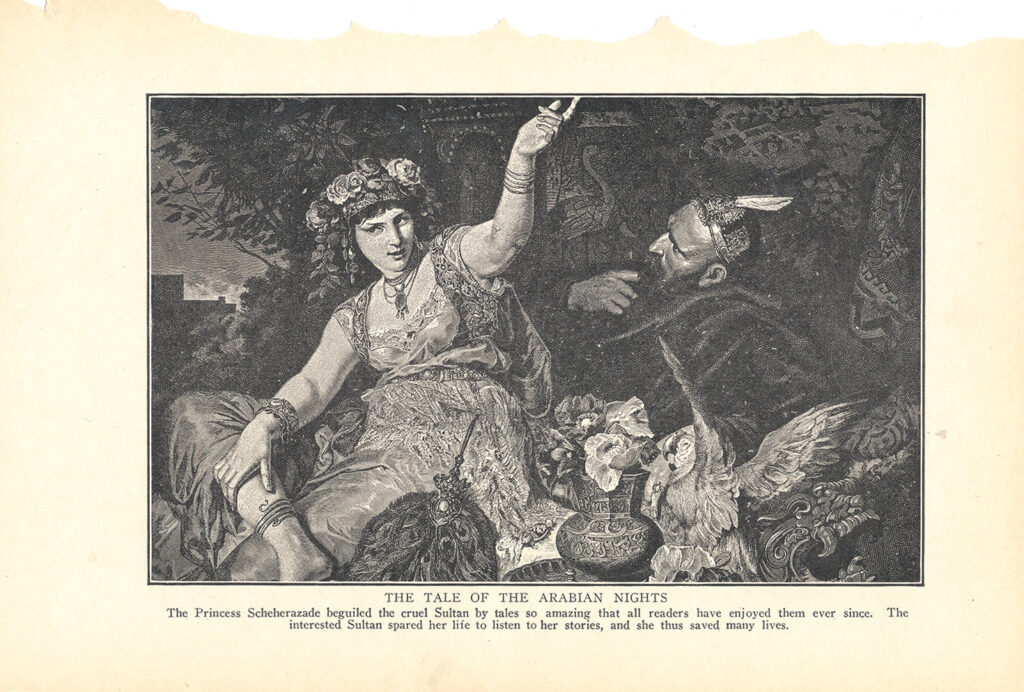

Artists and writers began to draw on Oriental folklore. Eighteenth-century France saw the first translation of A Thousand and One Nights, and the king received ambassadors from Persia. In this period, the East reciprocated, and the palaces of Isfahan had “occidental” decoration. Molière included Middle Eastern moguls in his plays and Turkish dances were worked into the ballets given at Italian courts for which Stefano della Bella (who had been to Egypt) designed the costumes.

Rembrandt painted the first Orientalist pictures which featured the distinguishing characteristics by which all Orientalists would measure. He respectfully and devotedly rendered the rich materials and architecture of the Orient, treating the environment more as his focus than the actual subjects of his paintings.

We must distinguish between those who developed a personal vision by visiting the East themselves and those who simply exploited a fashionable style. Orientalist painters included both those who traveled to the East and saw their actual subjects as well as those inspired by other sources to create oriental scenes for the European public. Illustrated travel books were popular in the 1700s, including a collection of costume engravings by Francis Smith. Such books featured images of architecture and local culture, which influenced and inspired many artists and allowed people to dream about visiting foreign lands without leaving home.

With the end of the Napoleonic wars, the East symbolized easy riches, unrestricted freedom, mystery, and passion. Romanticism inspired some to seek adventure in the East. The dignified Bedouins attracted many painters as much by their appearance as by being the last free men. And the harsh desert life was a haunting representation for sober spiritual awareness.

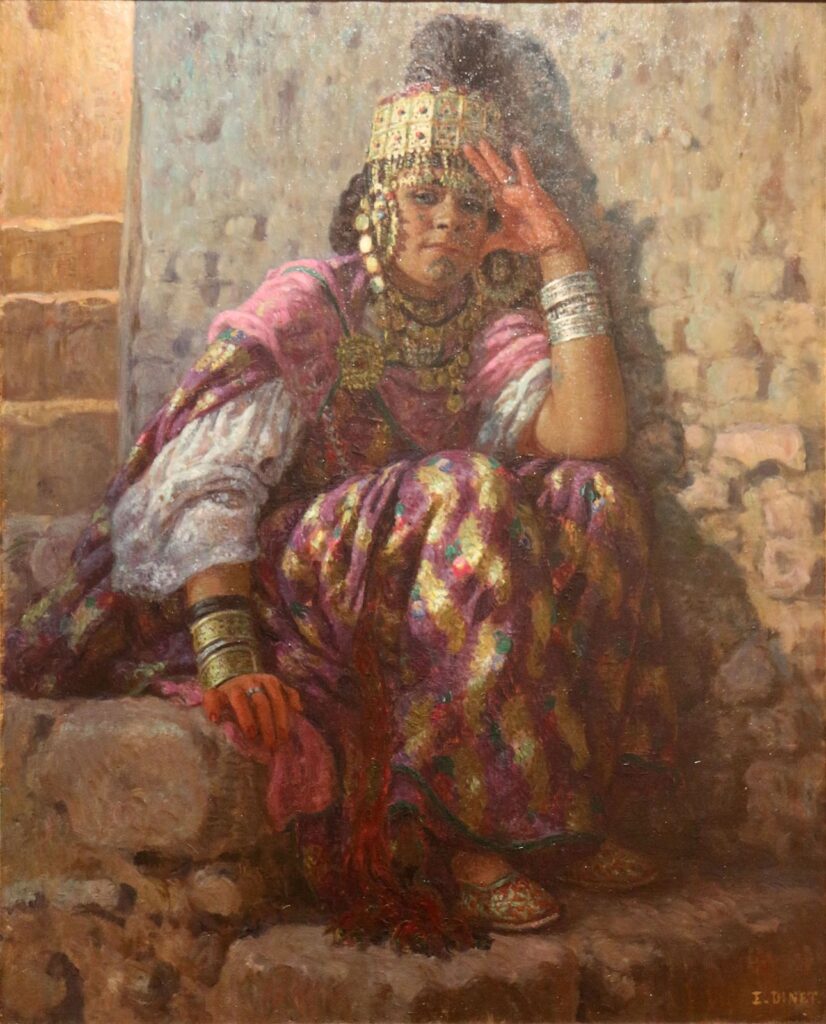

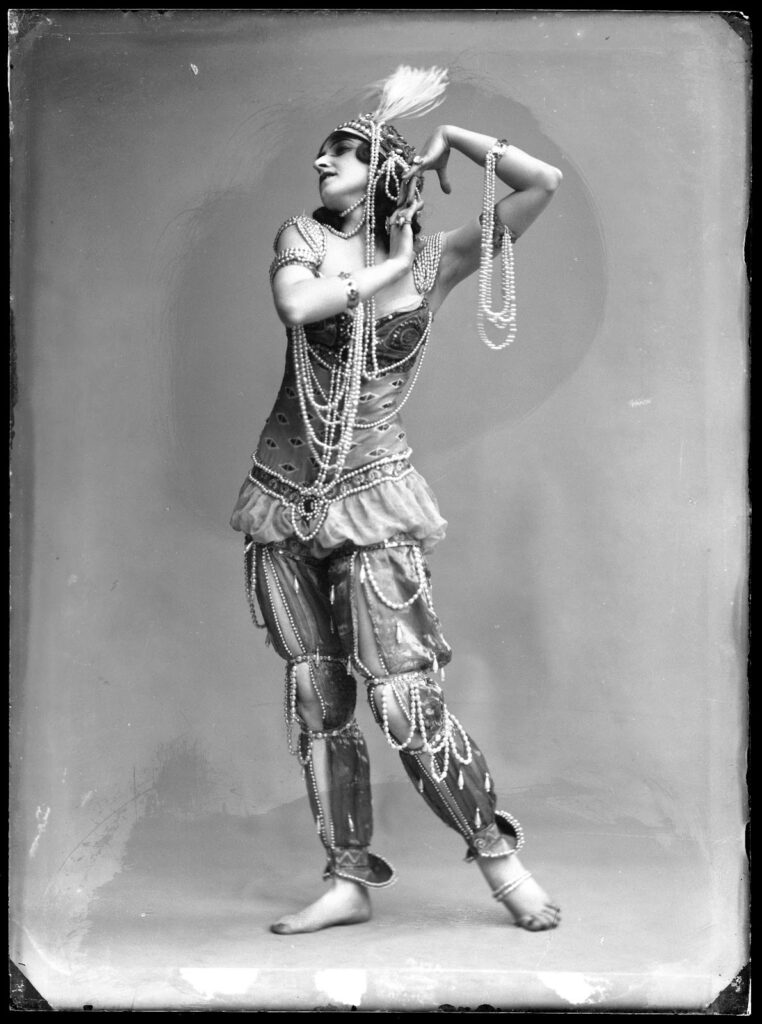

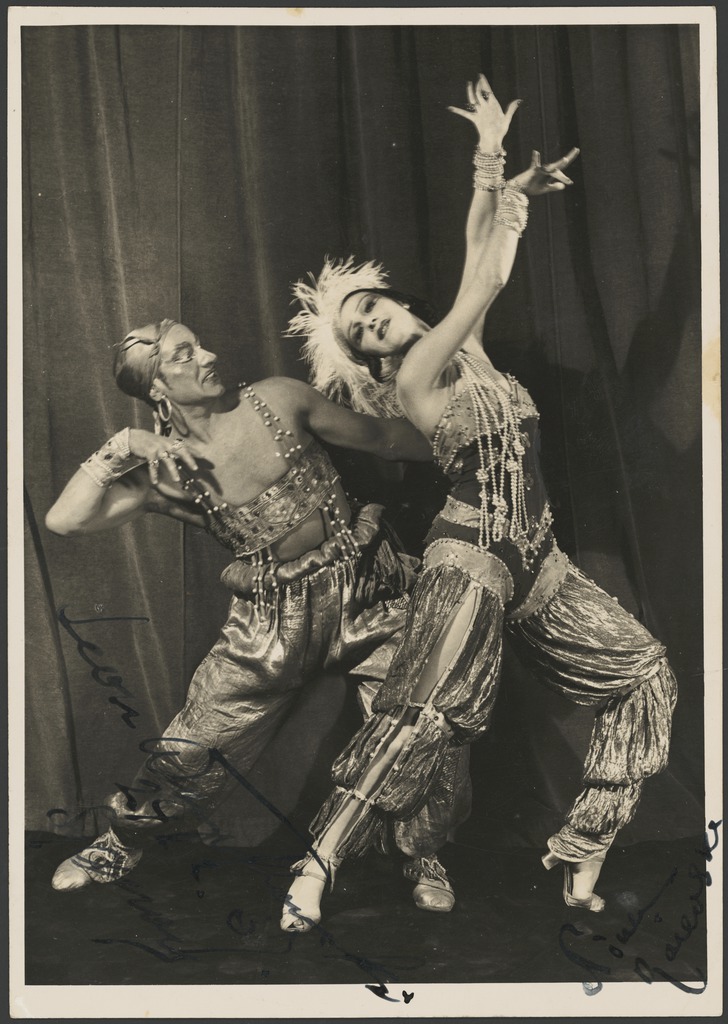

Many painted dancing girls came from France rather than Port Said. Toulouse-Lautrec sketched a belly dance on a stall in the Montmartre, but A.E. Dinet painted first hand the sensuality of Algerian Ouled Naïl. The numerous dancing girls in Algerian paintings belonged to the Ouled Naïl troupe; decked in light gauze and heavy jewelry, they had been a great success at the Exhibition Imoverselle of 1900 in Paris. Clairin visited Algeria several times and exhibited his dancer portraits.

There were English writers who became so thoroughly “Arabized” that their pseudo-translations were re-translated into Turkish, Farsi and Hindi. These in turn revived interest in certain Arab literary works such as The Adventures of Hajji Baba, Lalla Rookh, and The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam. True Orientalists inspired a number of armchair Orientalist poets, writers, and artists.

At the turn of the century, the Middle East was being colonized. Painters continued to send fascinating canvases to the salons as they sought to rediscover the ancient Egyptian “type,” but the end of the Orientalists came with the inauguration of the Suez Canal in 1869.

Nineteenth century composers were influenced by the Orientalists in operas such as Ricciardo e Zoraide, Semiramide, Lakme, The Italian Girl in Algiers, Bizet’s Djamileh, and Verdi’s Aida. These satisfied a public demand for more authentic and exotic decors. The Arabic dances in Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker Suite and Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade led to a renewal of Orientalism.

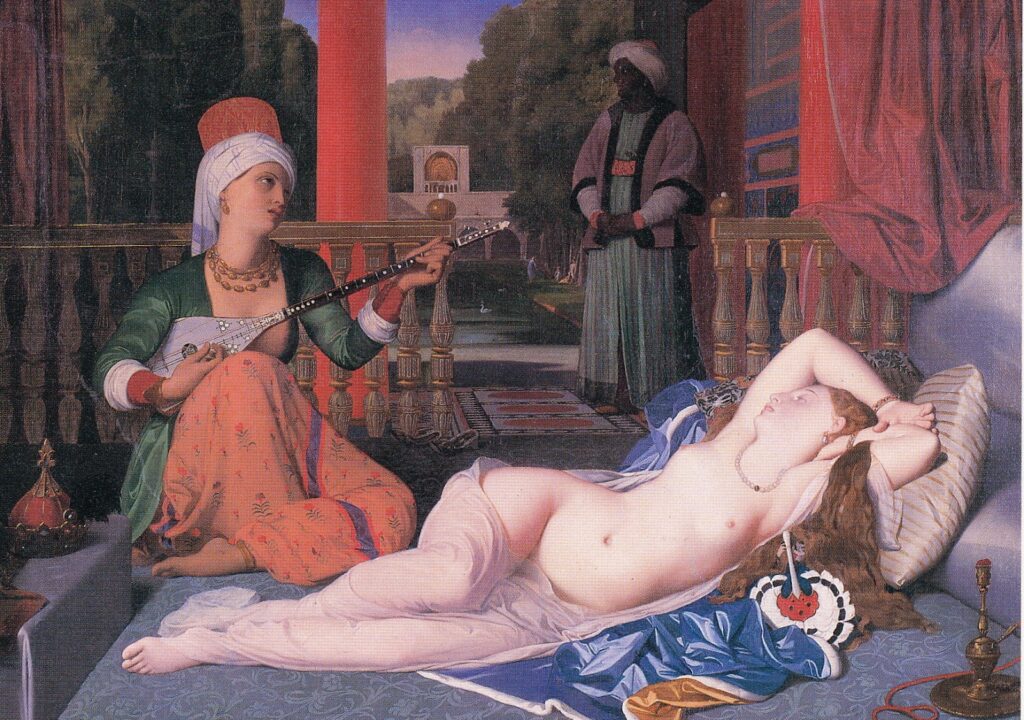

Victorian morality affected much of Europe, and Orientalism indulged a flirtation with a foreign culture. George Sand received his lover in Turkish slippers and baggy trousers. Balzac disguised duchesses as tarts and sultanas. Many ninetheeth century European homes had Arab clothing and décor. But the exploration of these sensual desires inspired art depicting erotic, and often violent, fantasies. Several Orientalist paintings included slaves. Slave markets enabled artists to place their nudes in authentic scenes. The slaves were usually white Circassian women who were sometimes shown as dancing girls. Such scenes were quite different from the true Oriental dances described by Arthur de Gobineau and painted by Eugene Giraud:

Then to an extremely slow and monotonous air accompanied by a jerky roll of drums, a dull, terse sound, the dancer, hand on hips, made some movements with only her head and the upper part of her body. She turned slowly on the spot. She looked at nobody, she seemed impassive and absorbed. Every eye followed her, everyone waited for her to do something, but she did nothing; and precisely because of this unfulfilled expectation she was watched more intently and breathlessly every moment.

These dancers were often boys, like those Flaubert saw in Cairo:

“…wide pants and an embroidered jacket, eyes made up with antimony; the jacket goes only as far as the pit of the stomach while the trousers, held up by a huge cashmere belt folded several times, do not start higher than about the pubis, so that the whole stomach, the loins, and the upper part of the buttocks are naked under a thin black veil. . .which ripples round the hips with every movement they made – the face expressionless under the greasepaint and the seat which is running down…”

Bibliography

The Academy, Arts news Annual XXXIII.

Julian, Philippe. The Orientalists: European Painters of Eastern Scenes. Translated by Helga and Dinah Harrison. Phaidon Oxford, 1977.

Smith, Frances. Eastern Costumes (engravings). 1763.