Habibi: Vol. 10, No. 7 (1988)

Toward the end of my dancing career I fluctuated between ecstasy and depression. On the one hand, I was elated when I did a good show and, on the other land, it depressed me that the musicians seemed to be out to kill me on stage by making me dance for such a long time. My shows averaged forty-five minutes when there weren’t too many customers. When we had a full house, they were longer. Was it always like that?

I thought it ironic when some people snickered at what I did for a living, concluding by my dance stamina that I must be somewhat of an athlete with an insatiable sexual appetite. In a day when people weren’t sexually free, “belly dancers” were looked upon as “loose” and generally “available”. The thought of socializing after my shows was totally ludicrous to me. I can still remember how my calves would shake uncontrollably as I climbed the stairs to my room in the New Rex hotel in San Francisco. Speed dancing was encouraged as the pulsating drums pushed to stir the audience into an excitement which stimulated liquor sales. Exhausted by my long shows, my preference for a nightly bed companion was my trusty heating pad. I often thought, since the hotel was very old, that one night my heating pad might cause a short in the antiquated wall plug, and I might not only become a “hot” cookie but a slightly “burnt” one at that! My fears were not as great as my bodily aches, though. And so, my nightly heating pad routine continued for years, anesthetizing the pain even from regular calf cramps, which were incorporated into my dreams of endless drum solos. It relaxed my muscles and lulled me to sleep until one or two the next afternoon when I would don my Mackintosh trench coat, dark glasses, and head kerchief, and venture out reluctantly in search of enough nutrition to sustain me for another night of marathon dancing. Until I married Suhaila’s father and had to stop dancing under threat of bodily harm, I could find no alternative occupation. I was happiest when I danced but it had become too physically demanding as it was becoming less artistically fulfilling.

Once I asked Maya Medwar what the usual length of an average Egyptian show was and she replied, “not over ten to twelve minutes”. She said, “They [Egyptians] primarily come to hear the singer, next they enjoy the musicals, and lastly, they tolerate the dancer.”

The norm becomes whatever is good for business, and dance routines have changed from country to country, state to state, and even suburb to suburb. Take for example the so-called five-part dance, which even I helped popularize, never fully understanding that I was perpetuating the elongation of the dance for the benefit of the business. As the dance spread from Middle Eastern-owned clubs with Middle Eastern audiences to American-owned clubs with primarily American audiences with Arab musicians, the audience was generally made up of males who couldn’t understand Arabic lyrics, barely tolerated the music, but loved to see the dancing girls. As a result, singers were not considered important, musicians were necessary, but dancers were the featured and highest-paid performers in the clubs. Also, in a club that catered to a neighborhood clientele (as versus high-turnover clientele), any dancer’s performance span was limited since the regular audience would quickly tire of her, no matter how talented she was.

I was prepared to perform at the beginning of the belly dancing boom in American clubs. Fortunately for my performance longevity, the tourist turnover made it possible for me to work in the same club for years. The audience saw me once and went back to wherever they came, probably never to see another Middle Eastern dancer again… that is until the teaching boom started many years later.

The dance changed drastically over the years I worked in clubs. Inevitably, dancers who worked together influenced each other. In the late 50s, many of the dancers were from Egypt, Turkey, and North Africa. After many complaints about the notorious behavior of many of these ladies, immigration imposed a ban on dancers coming into the United States. But, until that time, dancers who worked together influenced each other’s style, especially if any of them had an exceptional dance repertoire and unique costume ideas.

Arguments ensued as dancers accused each other of stealing steps, dance patterns, or music. For me it was difficult, after being groomed in an Egyptian style, to be hired in a club which specialized in Turkish music. Turkish dancers were acrobatic and incorporated floor work into their routine. Also, they included Karshilama somewhere in their dances. When club owner/musician Yusef Kouyoumdjian went to Egypt to record music for dancers in America, he had to teach the musicians Karshilama since it was foreign to them. The dancers in America had come to expect variety in music and rhythms mainly because of the diversity of Middle Eastern customers who frequented the clubs. In Egypt a musician would have to play only Egyptian music; in Turkey, Turkish music; in Persia, Persian music…and so on. But if a club owner wanted to please the cross-section of Middle Eastern immigrant patrons, he would go out of his way to learn some favorite songs from each country. And so it was that a dancer would have an Armenian song for her entrance like “Soude Soude,” then perhaps the latest rendition of “Cleopatra” composed by Muhammad Abdel Wahab from Egypt, and more than likely a Turkish finale with “Rampi Rampi”.

A similar mish mash is happening with the folkloric festival in Morocco. To encourage tourism, the Moroccan government is bringing together rural folk who have evolved individuality of dress, dialects, and dance. Taken out of isolation, the cultures begin to merge, sometimes to the annoyance of the purists.

In America, we have a curiosity about all Middle Eastern dance styles. We can assemble, in one show, examples of Egyptian, Turkish, Algerian, Moroccan, Tunisian, and Persian…not to mention rural offshoots of these nationalities. Here too, the Danse Orientale has taken its own character, borrowing a little from each period that came before. America is truly the “melting pot” of culture.

What is authentic? What is traditional? The long and the short of it is that culture is often bent to please the patrons. Whether it is a cross-cultural combination of songs, a sultan act, sword routine, snake dance, high platform shoes, audience participation, or, as well-known club owner Muhammad Saif used to say, “The last judge in the commercial business of entertainment is…the cash register”.

Photo Credits:

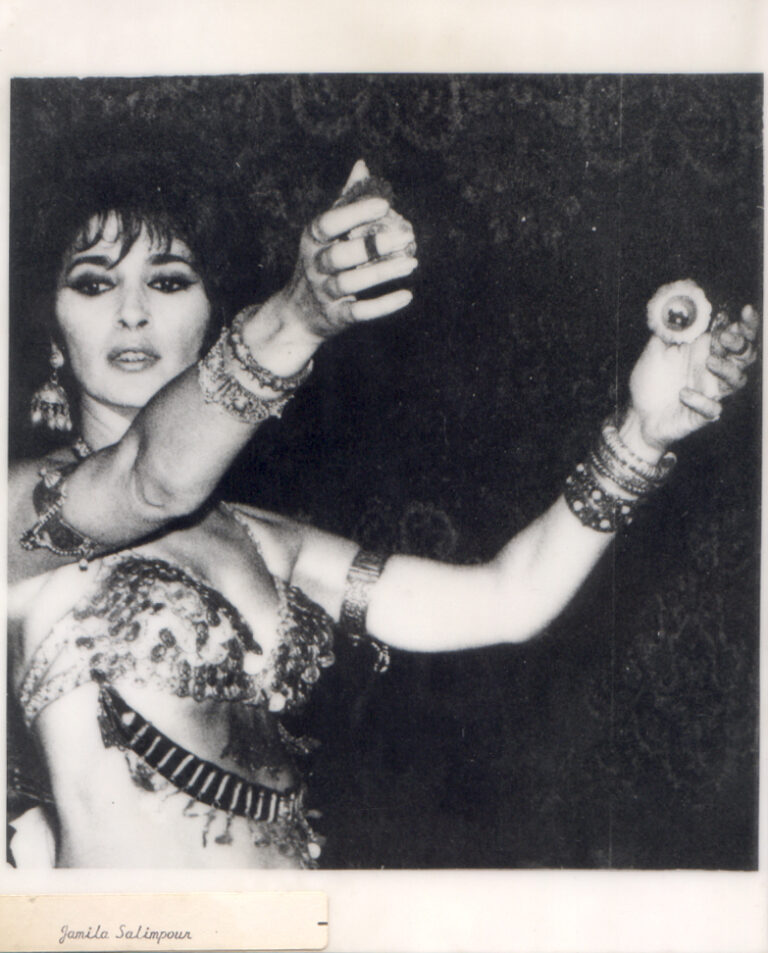

1. Jamila dancing in a nightclub.

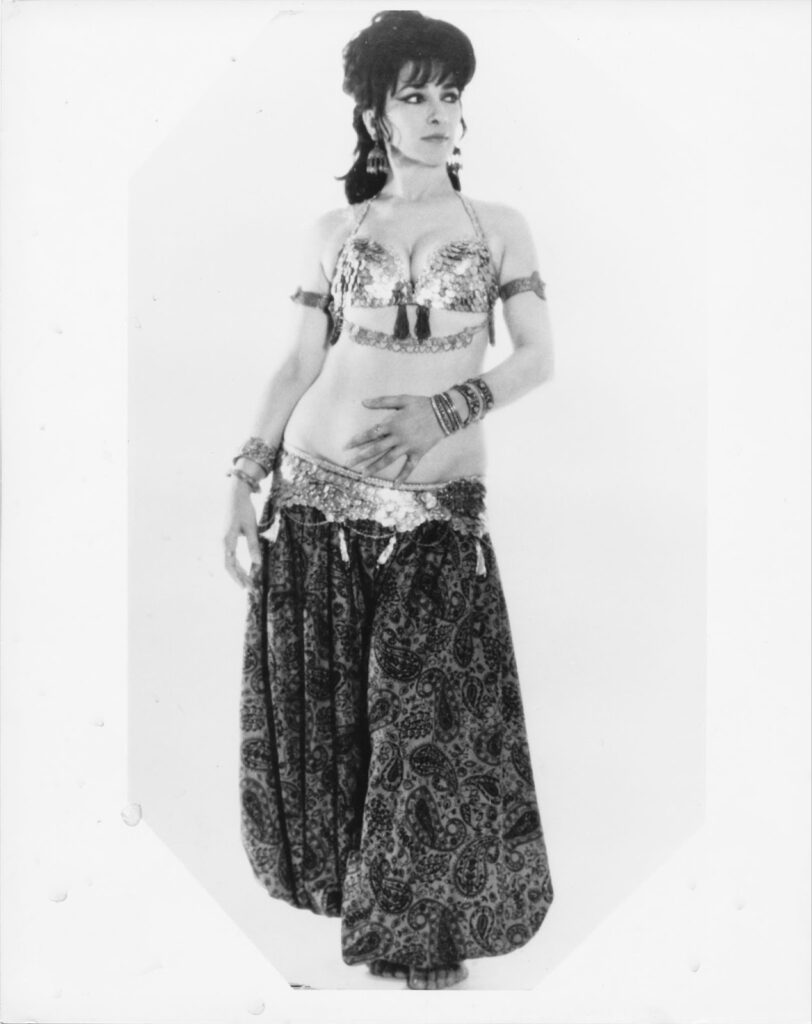

2. Jamila playing finger cymbals.

3. Jamila Salimpour in the early 1960s.

¹ Anatolian rhythm counted in 9/8 meter.

Jamila’s Article Book Main Page