Habibi: Vol. 4 Nos. 11 & 12 (1978)

An Interview with Louis Shelby Parts 1 & 2

Louis Shelby operated and owned the Cascades, an Arabian nightclub and restaurant in Anaheim just five minutes from Disneyland. He is the distinguished originator of the “Fez”, the first Arabian supper nightclub on the West Coast. His first love being music, he played for some of the most famous dancers and has sat in with well-known musicians. His violin repertoire included many of the old-time classics. With his distinguished past, Louis Shelby had some interesting comments about his business and insights into the future of oriental dance.

J: What was your background?

L: My parents are from what was called Syria and now called Lebanon. It was partitioned in 1949. My father and mother came to the United States when Syria was still under Turkish rule [in the early 1900s]. They had Turkish passports.

J: Was that a usual migration in those days?

L: The migration was very strong from the Middle East because the United States had open quota in the early 1900s and anybody that could raise one gold pound could come to the States.

J: When did you migrate to Los Angeles?

L: I came West in 1949, one hundred years too late for the Gold Rush! I came to California and I’ve never regretted it…beautiful country…God’s country.

J: How long have you been involved in Middle Eastern music? You are known as a musician first and a club owner second.

L: I started approximately at the age of seventeen which would bring us back to about 1943.

J: How did you get involved in music?

L: There were no nightclubs, per se, in Boston. There were Arabic coffee houses, much like what the Greeks had. Men would go there and sit and listen to recorded music—you know, if they weren’t playing Backgammon. My first introduction to Arabic music was in the coffee houses at the South End of Boston. Places where Khahil Gibran used to do some of his writing—you know, we used to see where he carved his initials into the tables.

J: So you became a musician in Boston?

L: Yes. When I started playing Arabic music I started on the piano, which left me high and dry on microtones—you know, quartertones and thirds of tones. It took two or three years to straighten my ear out to learn to hear the microtones and quartertones on the violin.

J: So, the musical tradition was not inherited?

L: In my case, my father loved to sing and was constantly singing around the house, but he knew nothing about the techniques of the Arabic music…Then, one of the most influential people in my life was Elia Baida who was from Lebanon and who was prominent in the art of the Baghdadi form of mawal (vocal improvisation); he was a marvelous recording artist. When he came to the United States he did some stage work, and he took me under his wing before I came to California.

J: Say, for instance, in the Indian tradition where you have a man who is the teacher and he has some students who are very select and they study with him over a period of years and then he allows them to accompany him in concert from time to time and then eventually will allow them to do a solo. Is this the same way that it is in the tradition of the Middle East musician?

L: No. No such schooling or nucleus of a musical center. No such thing ever existed in the United States, to my knowledge.

J: Did it exist in the Middle East?

L: Probably. Yes, I would say it does exist in the Middle East but would say that the opportunities for the upstarts were very limited. They would have to wait, virtually, for the [teacher] to die. For example, when [Muhammad] Abdul Wahab, a great artist in the Middle East, retired from singing, he selected Abdel Halim Hafiz, a young man who, in my opinion (and many people will disagree with me), was of very poor voice, rather than somebody who had a great voice. I think this comes from the Arab tradition of wanting to be outdone. So, Abdul Wahab, rather than pick someone like Wadi al-Safi who has a great voice, great technique, who may have outshone the master, Abdul Wahab, he might have outshone him…no chance!

J: What is the attitude of Arabs in general toward entertainers…do families encourage their children to study music and dance seriously?

L: My parents had a resentment against entertainment and entertaining. When my sister first appeared on an amateur night in a movie theater I thought my father and mother were going to lock her out of the house. She sang a song and I played the violin for her, and they were much against it. In fact, many times when I got into the Arabic music, my dad used to say, “Someday I’m going to break that violin over your head…you’re tiring yourself to no avail, no end, no future!”

J: Why did he think that there was no future in it?

L: Because entertainers in the Middle East [are] frowned on. The artist is frowned on.

J: You were the first Arabian club owner on the West Coast. What do you think of the current interest in the dance?

L: I want to start by saying that, frankly, I never heard the expression or term “belly dance” until the late 50’s when it first came to my attention and I resented it, personally. To me it is a dance which is native to the Middle East. I wouldn’t think of calling the Hawaiian dance a hip dance any more than our dance should be called a hip dance or a belly dance.

J: It is a native dance where? In which countries?

L: Well, in Syria and Lebanon I have seen in the villages, village girls will get up at home parties and do something similar to what the so-called belly dancer does. It’s not as put together, and it’s not as pronounced in the hip action, but they do leg work, you know, and the body will follow the leg work. If a village girl was unusually adept with her legs then naturally her hips would go with it, and, we would have something that is referred to today as a “belly dance”.

J: You wanted to make a point here about the attitude of Middle Easterners toward the dance?

L: The two points I wanted to make with respect to entertainment and the arts in general, music and dance in particular, is that 1) a relatively low opinion exists in the Middle East towards individuals that are engaged in these artistic pursuits. It seems to be improving in the last ten, twenty, thirty years. I can only attribute it to the excesses that took place or that people thought took place in Turkey among the [wealthy] and the sultans. 2) Another reason there is a low opinion about our music and dance and art is that it has not evolved like it should have. It seems to have stayed on an emotional level and never rose above the aspect of sensuality. In other words, poetry is a play on words, it’s about love, and indirectly about sex.

J: Which poetry?

L: All Arabic poetry from Al-Mutanabbi to the present time.

J: Who was Al-Mutanabbi…in what period?

L: He was one of the great poets. He might have been pre-Islamic; I’m not sure. The point is put in the words of Charles Makie (an educator in the Middle East, I took a philosophy class with him in Beirut), I heard him berating the students in the class for the level of the music and poetry and he called it “Suff Ghanam”—our poetry and our language and our arts are nothing but a play on words. Words for words’ sake. Why don’t we have odes, why don’t we have, like the Greek tragedies, great drama? Things that rose above the level of the waist, or the deeply emotional aspects of life? Why not something exciting? And to some extent, I think he is right. The music, say of Oum Kalthoum, has given us three generations of music and not much of it is above the level of the waist. It’s sensuous, it’s love yearning for human love, not love of God or love of art. None of these things have come out of the Middle East, not even in the Golden Era, when we had some like Ibn Khaldun. The North Africans came up with the first discipline with respect to sociology, before the Italians, in 1300 or 1400. Other than that, I’m not an academic of any high order so I can’t speak with authority; [Ali] Jihad Racy would be the man to tell you all these things, he has done the research and obtained materials that hitherto have not been found by anyone in this country. I feel that it’s a pity that the music development in the last fifty years has been more regressive than progressive, especially in Egypt. They’re very guilty of adaptation, copying, and stealing. They’re also guilty—the masters even—of being corruptible in producing commercial stuff like Abdul Wahab, whom I love dearly, produced just commercial crap for over half a century. And he produced no students worthy of mention, no school worthy of mention, he just made lots of money.

J: Can I put that in?

L: Yes, absolutely, that’s my opinion. And I’m entitled to my opinion, although Oum Kalthoum is great, for what she was doing and there will never be an Oum Kalthoum, another one, I personally consider her the eighth wonder of the world. She dwarfed the pyramids in my opinion, and I did hear her in person in Egypt and it’s an experience I’ll never forget, to my dying day. But I still say that it’s a pity that she died and the vehicle died with her. Whatever she was communicating died.

J: Who were some of the people who composed for Oum Kalthoum that you consider were some of the greats?

L: Well, Riad Al-Sunbati by all means. I think that his compositions were all together with Oum Kalthoum’s ability, technique, and personality. His music just fit her like a designer would design a dress for you, your body, and your personality; he designed it beautifully. Muhammed Qasabji before him was very good—played oud and also composed. In the new composers, of course [Muhammad] Abdul Wahab, the giant, merged with her and started to compose for her, but I don’t think his music reflected Oum Kalthoum’s personality or her simpatico with the music. Although they produced some nice things, I don’t think they will withstand the onslaught of time.

J: Do you think that Oum Kalthoum was classical or did she westernize it all?

L: Very little Westernization, by Arabic terms I would say yes—classical. But from the purely artistic sense, I would say no, not classical.

J: Well who would you say would be classical?

L: No one.

J: How long ago had that disappeared?

L: The classical forms? No music to my knowledge has withstood the onslaught of time—the only music known to my ears and again, [Ali] Jihad Racy would be a better man to give you a definite answer to that. The only thing we know is what we have heard in the last fifty to hundred years.

J: Where were orchestras used in the Middle East, and what instruments would have comprised it?

L: To my knowledge—which is secondhand—I have been to the Middle East but in recent times, so I can’t speak for the days of old, but I would venture to guess that the basic combination was—in the last hundred years—violin, oud, and qanun, and possibly nay and sometimes tambourine, depending on how large a group they wanted. In the last fifty years, Abdel Wahab in Egypt brought in the bass fiddle and some European instruments.

J: Do you approve of that?

L: I certainly do; I don’t care what ladder you use to get up there as long as you get up there.

The Arabic language is so strong, euphonic, so assonant, meaning what makes your sounds for poetry. If a language is assonant it lends itself to poetry very nicely. In Arabic you almost don’t have to say poetry or sing; when you just speak it is almost singing. Abdel Wahab who had almost no voice to speak of virtually spoke his songs. What made him was his delicate pronunciation and enunciation of the word. It was just fantastic; he could send you into ecstasy.

J: Now is it the language that’s used, is it able to be translated?

L: Yes, with difficulty when you translate from Arabic into English you run into some problems. Professors sit for hours trying to translate Ibn Khaldun into meaningful English and capture the forms and the prose. When I was at Berkeley, Drs. Popper and Fishelf were working on Ibn Khaldum for over ten, fifteen years, and they’re probably still working on it if they’re alive. It’s very difficult to translate and not lose the Arabic. It is a Semitic language, and it’s structured in such a different way than the Indo-European languages.

J: Do you have to develop a much larger vocabulary when you speak in Arabic?

L: Not necessarily. There are nuances, words that you can say several different ways; you can say “I love” in many ways which could distinguish the level of love in a sense, like love for a child, love for family, love for a wife, love for a woman, love for a mother, love for a father, and so on. It’s sort of hard to do that in English without a whole slough of words to explain yourself. In Arabic you can use a word, although I’m not a linguist, you can use several words to distinguish your feelings for a particular subject or object. It’s a broad language in that sense. But the thing that interests me most about Arabic language—and why I say to you when you come into language—the word is the king. The Arabic word comes before anything.

This article was published in Jamila’s Article Book: Selections of Jamila Salimpour’s Articles Published in Habibi Magazine, 1974-1988, published by Suhaila International in 2013. This Article Book excerpt is an edited version of what originally appeared in Habibi: Vol. 4 Nos. 11 & 12 (1978).

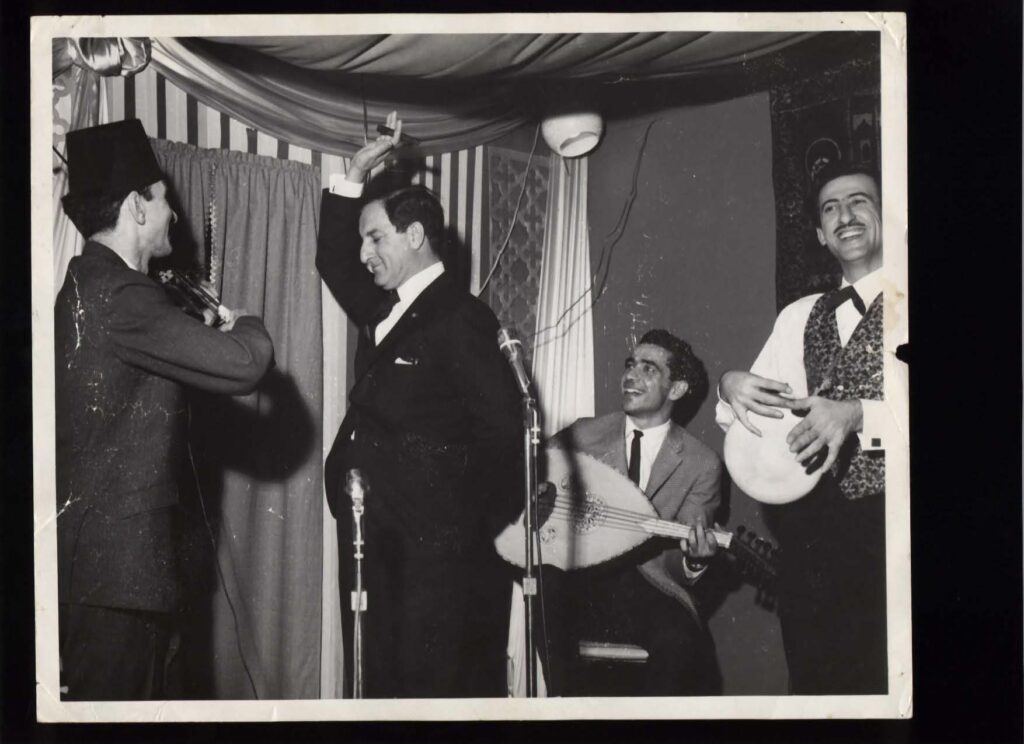

Photo Credits:

- Louis Shelby and Danny Thomas at The Fez. Louis Shelby playing violin with other musicians at The Fez nightclub in Hollywood, Los Angeles, CA. Photo features the actor Danny Thomas (1912-1991). Thomas was born Amos Muzyad Yaqoob Kairouz). His parents immigrated from Lebanon to the U.S.

- The Fez Publicity Shoot. This photo was part of a promotional campaign for The Fez nightclub in Hollywood, Los Angeles, CA. The photo features Louis Shelby, other musicians, and one of the dancers.

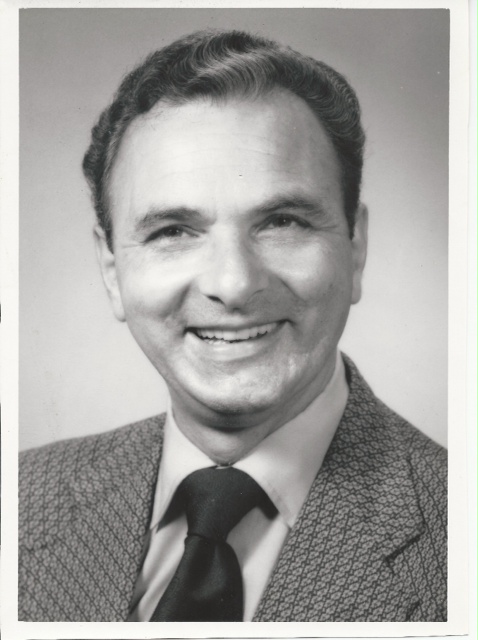

- Lou Shelby Portrait Headshot.

- Lou Shelby closeup excerpted from a larger publicity photograph.