Habibi: Vol. 1, No. 2 (1974)

After World War II, Los Angeles was a city in which apartments were at a premium, and migration from all parts of the United States was taking place at an astounding rate. World War II veterans had traveled around the world to parts heretofore unknown to them, and many of them settled in areas other than their hometowns. So it was for the Takorian family formerly from Boston, Massachusetts, formerly from Alexandria, Egypt.

Hyganoosh Takorian, the matriarch, was typical of the oriental woman of her day: an early knowledge of household accomplishments but not too much formal education. In Egypt she learned to embroider at the age of six and into her teens contributed to the support of her family by doing gold thread work on military epaulets and Turkish bath wooden shoes. She was an excellent cook, fastidious housekeeper, expert seamstress, tatter, crocheter, knitter, and, of course, doting mother. Hyganoosh did not consider herself knowledgeable in worldly affairs, but she spoke five languages fluently. She was born in Turkey, so she spoke Turkish, but her parents were Armenian, and only Armenian was spoken in the house. The tragedy of Turkish-Armenian hostilities at the turn of the century drove her family to Egypt, and so she picked up Egyptian Arabic as her mother tongue (she considered herself an Egyptian because she said Egypt took them in and gave them a home). She learned Greek from a Greek neighbor in Alexandria and learned English when she moved to the United States.

Hyganoosh immigrated to America with her husband and settled in Boston. At the height of the Great Depression, her husband disappeared, leaving her with three children. Refusing federal aid, she kept the family fed by being domestically inventive (such as sewing for neighbors) and by occasionally taking in roomers (only Armenian) for extra income. When the children expressed the desire to move from Boston to California, she took in an Armenian boy to lessen the burden on her children for her support. I worked with her daughter and, after meeting Mama¹, I was invited to move in. It was with the inspiration, encouragement, and guidance of Hyganoosh Takorian that I was destined to become an oriental dancer.

About once a week, Hyganoosh invited a few girlfriends to her Turkish coffee get-togethers, and, if they were fortunate, someone would be invited who could read the coffee ground sediments. The procedure was to drink the Turkish coffee and then turn the cup upside down. After an hour or so of conversation (by that time the sediments had made their patterns on the overturned cup), the reader would tell each person’s fortune. Every home had oriental music and, in Hyganoosh’s case, she had Turkish, Greek, and Arabic music on 78 rpm records. The women were familiar with the melodies, some records meant for listening or singing along, and, of course, the inevitable ciftetelli dance music. Hyganoosh had no qualms about getting up and dancing and, by all Middle Eastern standards, was very “hanum” (ladylike). One by one, most of the women would get up and assume a foot stance which I was later to teach as “Basic Arabic”². They were all home dancers, none of them the caliber of the professional, and, indeed, none of them would want to be a professional dancer. In Armenian circles, no young girls were encouraged to dance; even if they did modest Armenian dances, their mothers would say, “Don’t shake, don’t shake.” It was thought a brazen Armenian girl would not make a good wife, but I was often encouraged to get up and dance at these get-togethers. As time passed, I would dance more and more frequently until I was expected to dance at whatever function was given.

Almost from the day I moved into the Takorian house, I was fortunate to be in the midst of a family that loved music and looked forward to visiting musicians and dancers from the old country. Once a month Hyganoosh and I would go to the La Tosca theatre on Vermont Avenue where they would show an Egyptian movie (occasionally Turkish, although Egyptian movies were more prevalent). It was at that time that I began analyzing professional dancers featured in the films, and my favorite was an Italian-Egyptian by the name of Tahia Carioca. It was to her that I credit my inspiration to imitate, seek out, and become an oriental dancer.

This article was published in Jamila’s Article Book: Selections of Jamila Salimpour’s Articles Published in Habibi Magazine, 1974-1988, published by Suhaila International in 2013. This Article Book excerpt is an edited version of what originally appeared in Habibi: Vol. 1, No. 2 (1974).

¹ Jamila’s familial name for Hyganoosh

² Now codified as “Arabic 1” in the Jamila Salimpour format

Photo Credits

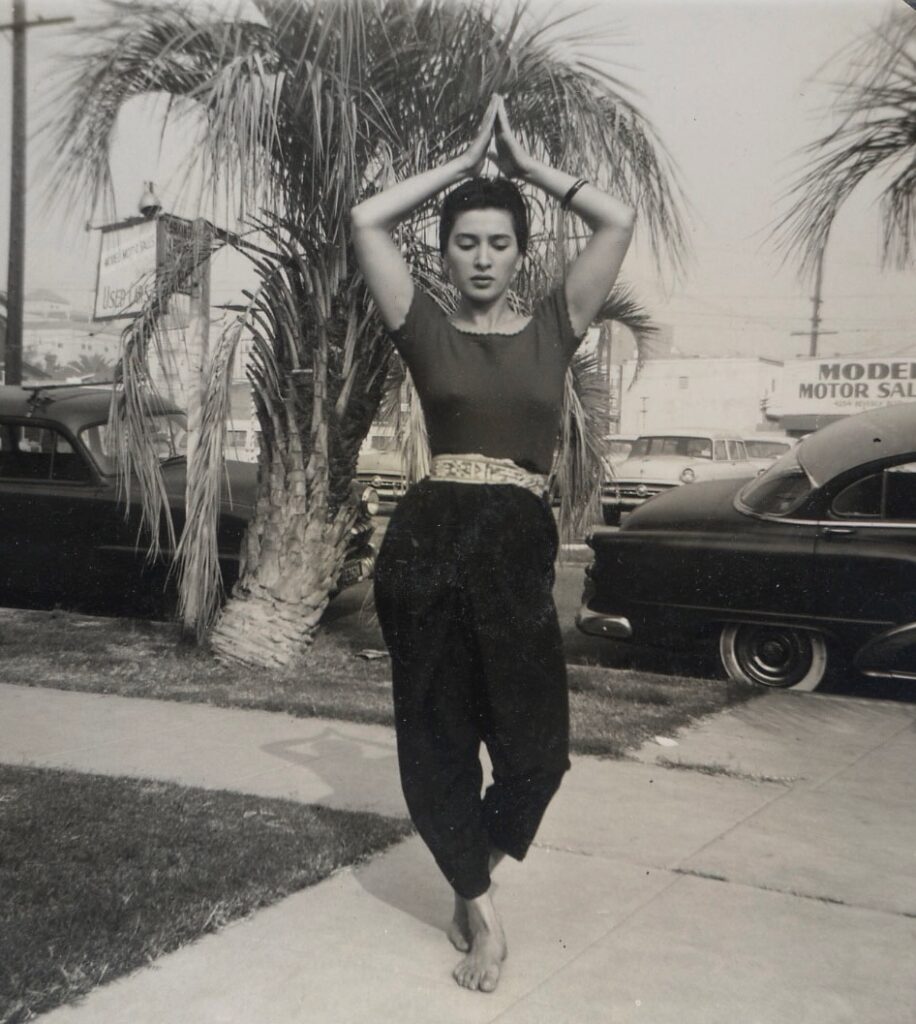

- Jamila pose, circa early 1950s in Los Angeles, California. From the Jamila Salimpor Danse Orientale archives.

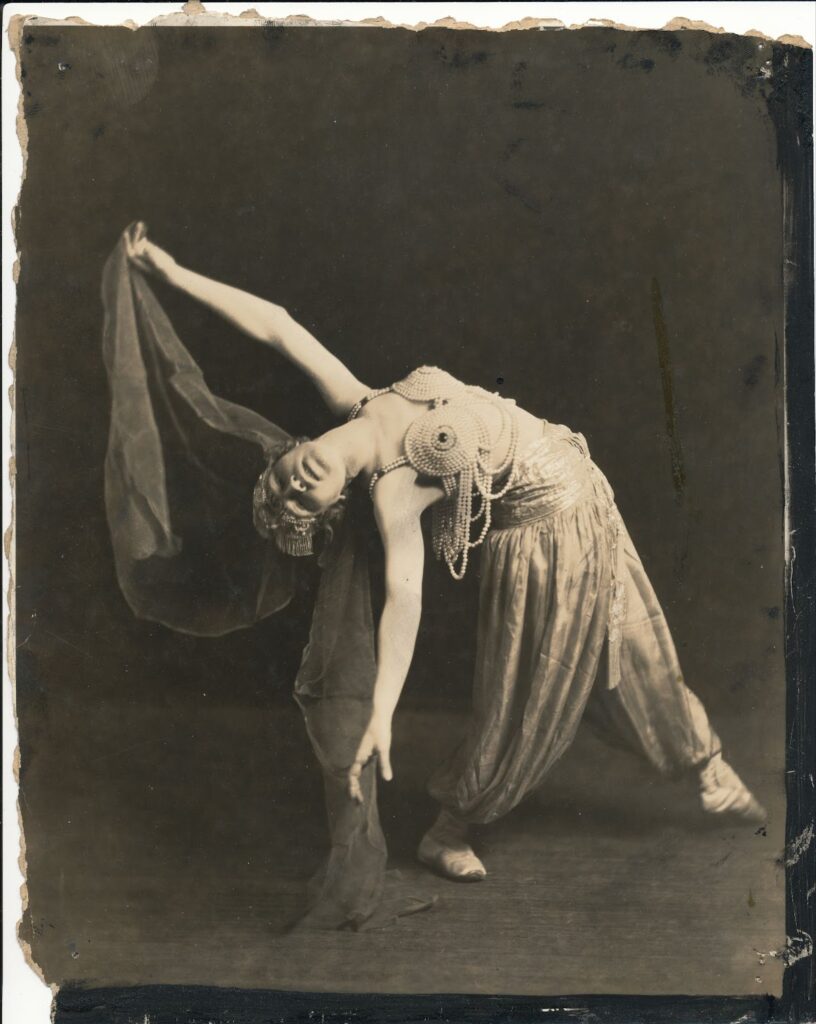

- Unknown dancer from the Ballet Russes, photographer unknown, Public Domain.

- Léon Bakst, La Sultane Bleue, 1910. A costume sketch for the ballet Schéhérazade.