Habibi: Vol. 3 Nos. 3 & 4 (1976); Vol 17, No. 3 (1999)

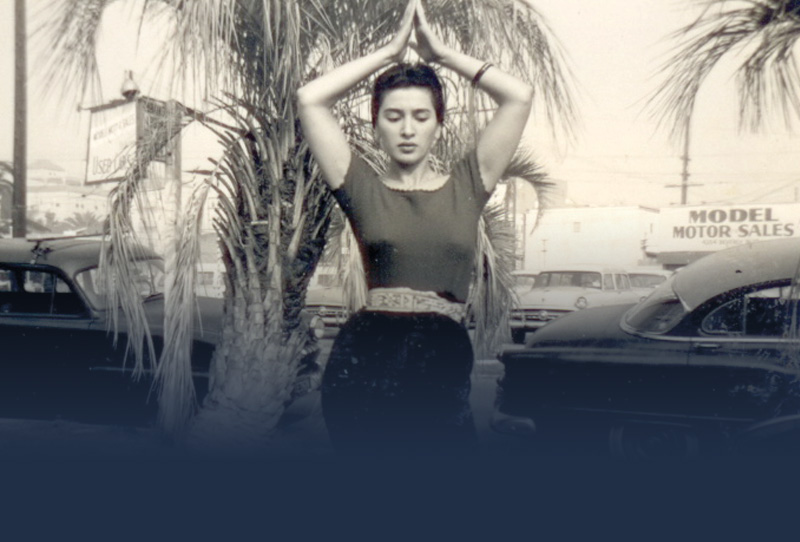

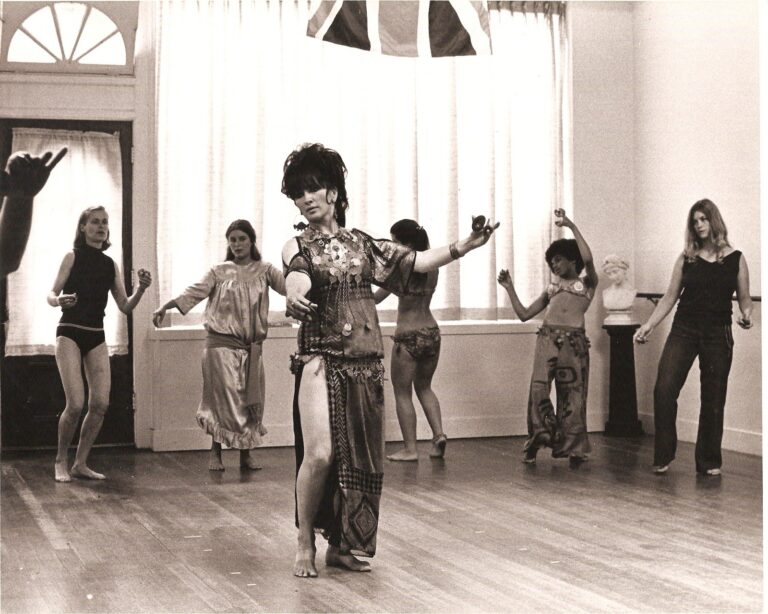

When I moved to Berkeley, California, in 1966, it was alive with students who, stimulated by the Indian music of Ravi Shankar, were ready to listen to and look at yet another foreign import from the Middle East. The reaction to my dance ads was encouraging, and I watched as students absorbed the movements and transitions, and began responding to the music. As my teaching techniques became more refined from the experience of teaching four classes each week, the students began to learn more quickly. Three of my teenage students who were attending Berkeley High School taught what they had learned to all their girlfriends, and they in turn taught all their girlfriends. The ensuing result was spontaneity without technique, and nobody seemed to care! I was told that they were asked and did perform for their friends, but they were by no means ready to dance publicly.

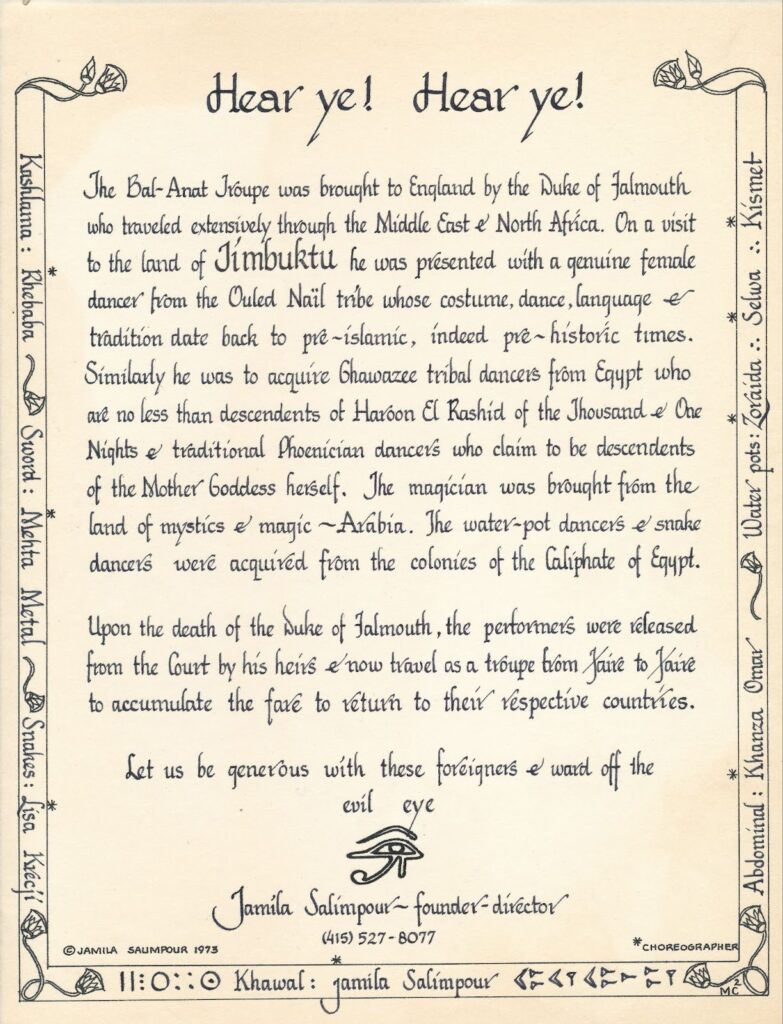

Many of the students were disappearing from my Saturday classes. I was in for a professional shock when one of them invited me to what they called the Renaissance Pleasure Faire, which they had been attending on Saturdays. They explained that it was an arty affair, like a huge outdoor circus set in the sixteenth century. It featured food and entertainment from the period, along with appearances of her majesty, “Queen Elizabeth,” who gave an award to the best craftsman exhibiting at the Faire. Jugglers, magicians, mummers, Punch and Judy, and any type of entertainment were encouraged.

One enticement was that anyone who came in costume, period or otherwise, was admitted without charge. I was admitted free because I was covered from neck to ankles in a Bedouin costume, which constituted being in costume to the Faire people. All of Berkeley was there, and of course, all the Berkeley High School girls and their girlfriends’ girlfriends were there in belly dancing costumes. The scene I encountered upon entering the Faire was beyond belief. I tried to make my way, either crawling at a snails pace or being immobilized completely, because every five feet a crowd was gathered around a wiggling novice, completely abandoned in her interpretation. One of my students recognized me, and pulled me along to meet the entertainment coordinator, an exhausted, harassed woman named Carol Le Fleur. She greeted me with: “So you’re the belly dance teacher who is responsible for all this!” She tried to half smile as she got her message across. “Listen,” she went on desperately, “You’ve got to do something about this. I mean, it’s not that I don’t like belly dancing or anything like that. But there are just too many of them. They’re all over the Faire, stopping traffic, in the road, on the stages, crawling out from under rocks, falling out of trees…They’re everywhere.” She continued smiling, but she was desperately serious. “We can’t have this next year. It has to be organized: only on stage, limited to thirty minutes. Enough is enough!” I assured her that I would explain this to my students and that we would cooperate. I bid her good cheer and continued on through, rather, I should say, tried to push my way through the Faire to see for myself what was going on.

At that time the entertainment was not organized. Throughout the Faire, there were several small stages and one large stage called the Ben Johnson on which all the pageantry took place. Anyone, entertainer or not, could go on stage and do anything they wanted to do. The Faire people said nothing modern, but some bluegrass and jazz could be heard until word got back to the Faire guards, who would explain that the act should be period.

Where did belly dancing fit into all of this? Who knew and who cared! It was a crowd-pleaser, and I think that did it more than anything…besides the costumes were attractive. The caliber of students performing at the Faire was below par.

It was in September 1968 that the troupe idea was born in my mind, and I asked a few of my more advanced students to join me at the Faire. Although we had no musicians that year, I drummed for a half-hour show, playing the necessary tempos for each student, assisted by a folk dancer who had recently acquired a darbouka and attempted to learn to play on stage. What a mess! What a sad representation! But nobody knew the difference but me. I smiled and supported each of the dancers, and the audience loved it.

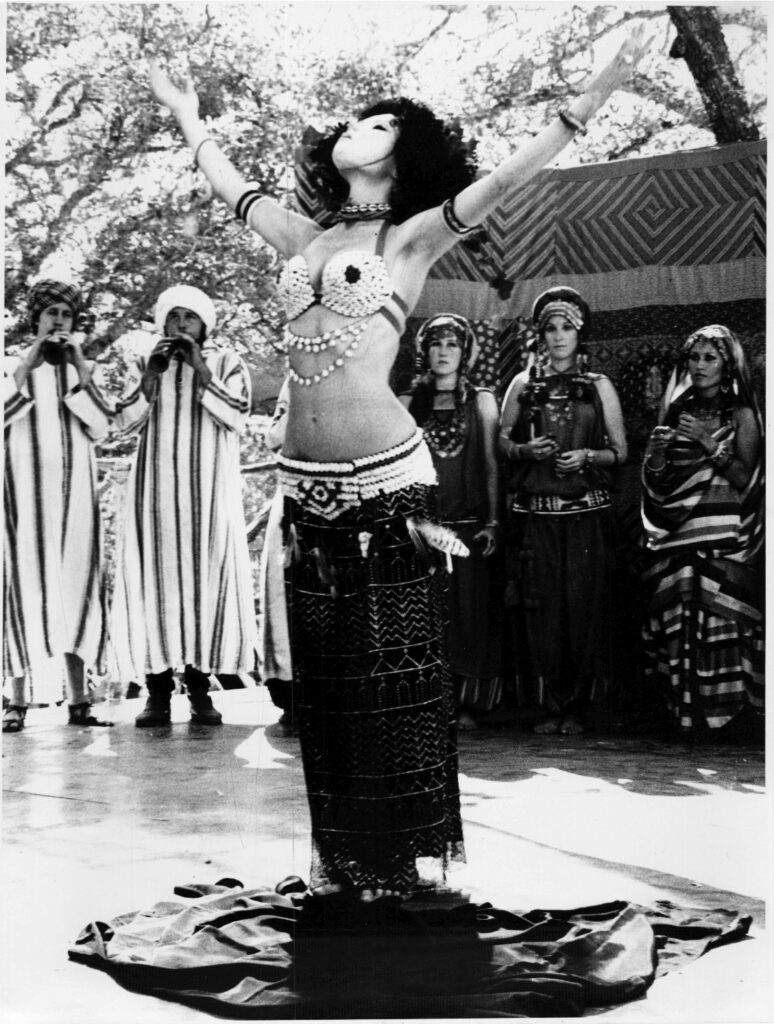

From this humble beginning, the nucleus of my troupe was formed. In looking for a name for the troupe, I wanted to honor the mother goddess, Anat. I preceded her name with bal, the French word for dance. Thus, Bal Anat: the Dance of the Mother Goddess.

I knew that the cabaret format would not have been suitable for the Faire, and that is when my Ringling Brothers Circus background came to the rescue. I patterned Bal Anat after a circus-like variety show that one might see at an Arabian festival or a souq (Arabic for “market”) in the Middle East. Included were a cross-section of old dance styles from the Middle East. In addition, we had two magicians, Gilli Gilli from Egypt and Hassan from Morocco. Our Egyptian acrobatic dancers were as supple as their predecessors. We even had a Greek math professor from the University of California, Berkeley, who picked up a table with his teeth, all the while balancing Suhaila on top of it.

It was a format with a look that was eventually imitated all over the United States, whose practitioners sometimes knew, but more often did not know, from where it came. Indeed, many people thought it was the “real thing” when, in fact, it was half-real and half-hokum. Our leaflet informed the audience that we came from many tribes. Perhaps that is where the expression ”tribal dancing” originated. The “tribal” trappings of the show grew naturally each year.

In 1969, we dealt with the problem of music. I had always performed indoors and was used to amplified musical instruments. The problem in replicating a sixteenth-century outdoor Faire was that they wanted it to be completely authentic, and that meant no electricity, no batteries, no “piggies” (portable amplifiers), and no twentieth-century knob volume tricks. We had to go back to the pre-nightclub music of the tribes. To project outdoors, I accumulated as many noise makers as I could, such as finger cymbals, sistrums, tambourines, wooden clappers, darbukas, mijwiz, tabl baladi (large base drum held in place by strap), and defs (large frame drum held like a tambourine). The troupe was instructed in the zaghareet, the ululation which for Middle Eastern women expresses exhilaration.

The professional musicians I had worked with were not interested in getting up early, driving out to the boondocks, playing in the dust, and worst of all, not being heard or paid a decent wage. Only Louis Habib, a full-time barber, and sometime oud player, volunteered to play for us “just for fun”. It wasn’t long before it wasn’t fun for him anymore. The oud is a delicate instrument that was easily overpowered by the drums. Not so with the mizmar (Egyptian oboe). After teaching to mizmar taped music for years, I finally managed to collect a few of them and began to ask craftsmen at the Faire if they would like to blow into the things. We always had craftsmen at the Faire asking to “sit in”. I wanted some structure, but it was getting hard to control. The first good, almost Middle-Eastern sounding mizmar player we had was Ernie Fishbach, a craftsman and musician who dabbled in Indian music and had a Middle Eastern flair. He became the backbone of our Middle Eastern orchestra, teaching willing enthusiasts to puff up their cheeks for thirty minutes, three times a day. The ear-piercing, hypnotic shrieks of several mizmars, with tabl baladi and multiple darbuka accompanying the dancers, became, for many of our fans, the sound of the Faire.

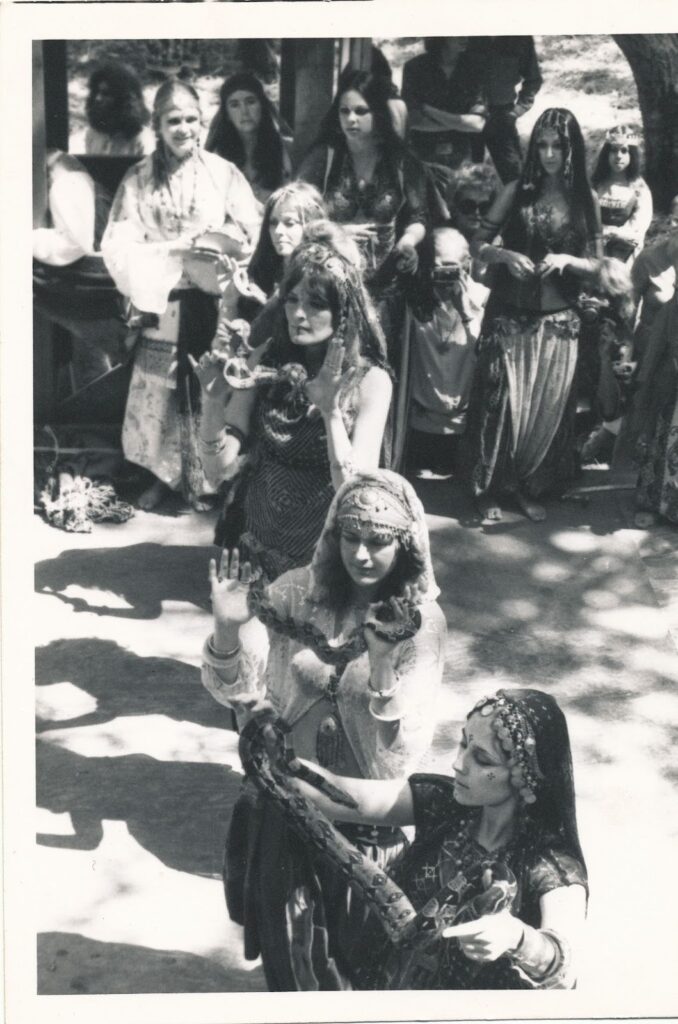

In 1969, I accidentally used snakes. I say accidentally because we had a magician who used a two-headed Indian snake as part of his act. He would show the audience an empty frying pan to which he applied flames, and after twirling it in the air a couple of times he would pull out a snake. I noticed that the audience reaction was repulsion and disgust as he put the almost unconscious animal in a sack until the next show. Since his treatment of the animal was lacking in compassion and I felt the snake might be killed, I insisted that he give the snake to me. When he did, I simply stared back at the thing. What do you do with a snake? What would it do to you, if it had the chance? I soon learned that not all snakes are venomous and that mostly they lay around until they are hungry. No one in the early troupe would handle the snake. When I suggested we add variety and “hokum” to the show, one of the replies was, “I don’t want to be a freak.” So I did everything. I sang, danced on water glasses while holding a snake, and played drums in between. I have never seen or worked in person with a dancer from the Middle East who used a snake. I know of Indian fakirs who use snakes, but they do not dance with them. The snake dance was my culmination of the trials and errors after that first accidental possession of the snake. I never meant to suggest by our performance that it was or is done traditionally by dancers in the Middle East.

It was difficult at first to get the girls to wear the traditional costumes, which often covered from head to toe, because they wanted to display their forms. So I covered up, and accompanied them in their dance solos.

In my early classes in Berkeley, even though I fed the students steps and explained the phases of the professional dancer’s cabaret dance, I found that when they were asked to do an improvised solo, most of them either blanked out or did all of their steps in two minutes and looked helpless for the rest of their dance. I introduced a choreography to help them to be comfortable without having to think about which steps they were going to do. Secure in the knowledge of what was coming next, hopefully they would be able to project. This worked well, and the students understood much faster which steps to use for entrance, and what to do during the taqsim, etc. At the Faire, each girl felt that she was different in her projection, but I noticed that there was too much repetition, as one performance after the other consisted of the three-part dance (entrance, taqsim, and finale) and then the bow. The faces changed, but the dance was the same.

Years before I had seen a print by Jean-Léon Gérôme of a sword dancer done during the Turkish occupation. In 1971, I had a student dance with a real Turkish sabre, balancing it on her head, and copying the painting. For her finale, she did a back bend and plunged the sword into the wooden stage where it stood upright as she retreated to make room for the next dance. By 1971, I had begun to choreograph group dances, and I later choreographed a group sword dance.

That same year I choreographed my first group pot dance, in which three girls balanced large gourds on their heads and danced standing and on the floor. I was inspired by a scene in a Tunisian palace from the movie “Justine”, based on the book by Lawrence Durrel. About thirty Bedouin women were dancing with pots balanced on their heads around five mizmar players and one tabl baladi player.

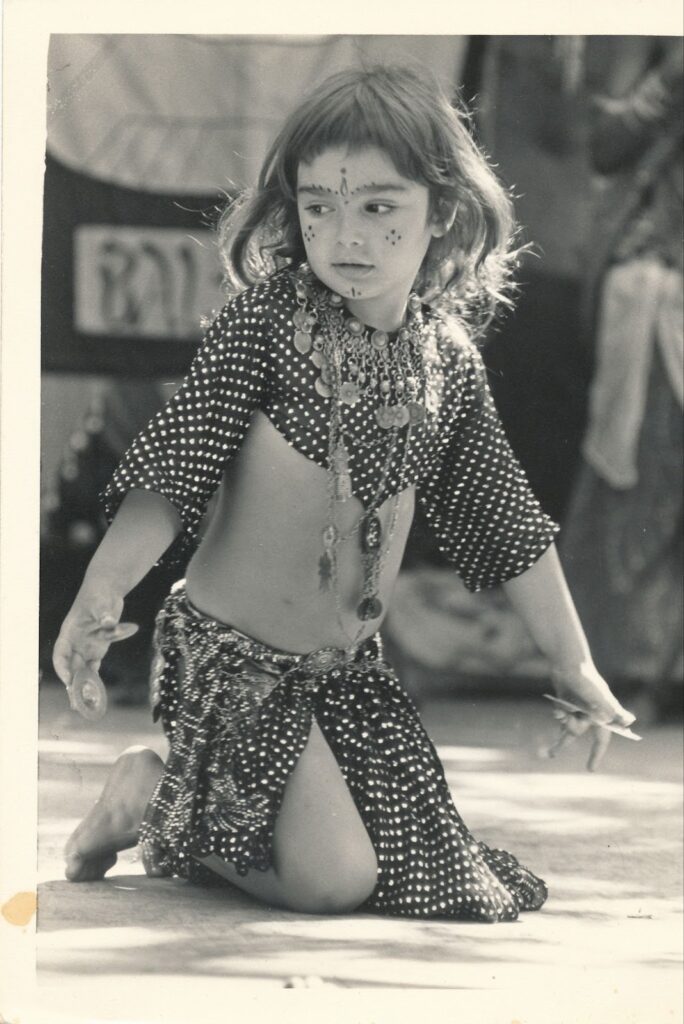

I decided that the following year a variety of dance styles would be the key. At age 3, Suhaila opened the show. I added the water glass balancing dance, which I taught in class. We had an Ouled Nail dancer from Algeria. The karshilama dance was a replica of the folk dance done in Turkey, which many cabaret dancers tack onto their finale as an exciting finish. A Mother Goddess mask dance was later added as an opening number, my expression of the primitive origins of the dance.

At one point, I added an Indian katak dance, which combined the Arabic and Indian foot dance with spoken bols. However, a great male katak dancer, Chitras Das, had recently arrived in the United States and was teaching at the Ali Akbar School of Music. When I saw him perform, I decided that out of respect for his genius I would never attempt to present another watered-down katak dance when his talent and training were so readily available.

In 1973, I completed research on the role of the male dancer in Middle Eastern dance, and the first Moroccan tray dancer was introduced to the United States in our show. The dance was inspired by stories, as well as the photo of the venerable, distinguished, calm, and capable-looking gentleman from the Time-Life book on Moroccan cooking.

The abdominal dancers breathed life into the paintings of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingre, dancing in one spot as dancers did without picking up their feet. Only the pelvic area danced, and the face was ivory, with no expression. Were they human, or statues?

That year, a few of my students were inspired to show their own choreographic talents. The Turkish karshilama, the abdominal dance, and the sword dance were arranged by Rebaba, Khanza, and Meta, respectively. This was a thrilling moment for me when I was able to appreciate my students’ work. Several students eventually left to form their own troupes patterned after Bal Anat.

I have heard a few expressions lately: West Coast tribal, East Coast tribal, and American Tribal. I have also heard of the “ethnic police,” an expression I find very amusing. Tradition is not static. Every generation draws from the past. Evolving from the saloon and street performer, to the nightclub and concert hall, whether it is baladi, cabaret, or folklore, the oriental dance will endure.

This article was published in Jamila’s Article Book: Selections of Jamila Salimpour’s Articles Published in Habibi Magazine, 1974-1988, published by Suhaila International in 2013. This Article Book excerpt is an edited version of what originally appeared in Habibi: Vol. 3 Nos. 3 & 4 (1976); Vol 17, No. 3 (1999).

Photo Credits:

- Jamila Salimpour teaching students in Berkeley.

- Bal Anat declaration created by Jamila Salimpour.

- Bal Anat masked Mother Goddess dance.

- Bal Anat musicians with Jamila Salimpour.

- Bal Anat snake dancers.

- Bal Anat performance by Suhaila Salimpour, age 3.

- Bal Anat Moroccan dancers.

- Rhea, the first Bal Anat sword dancer.

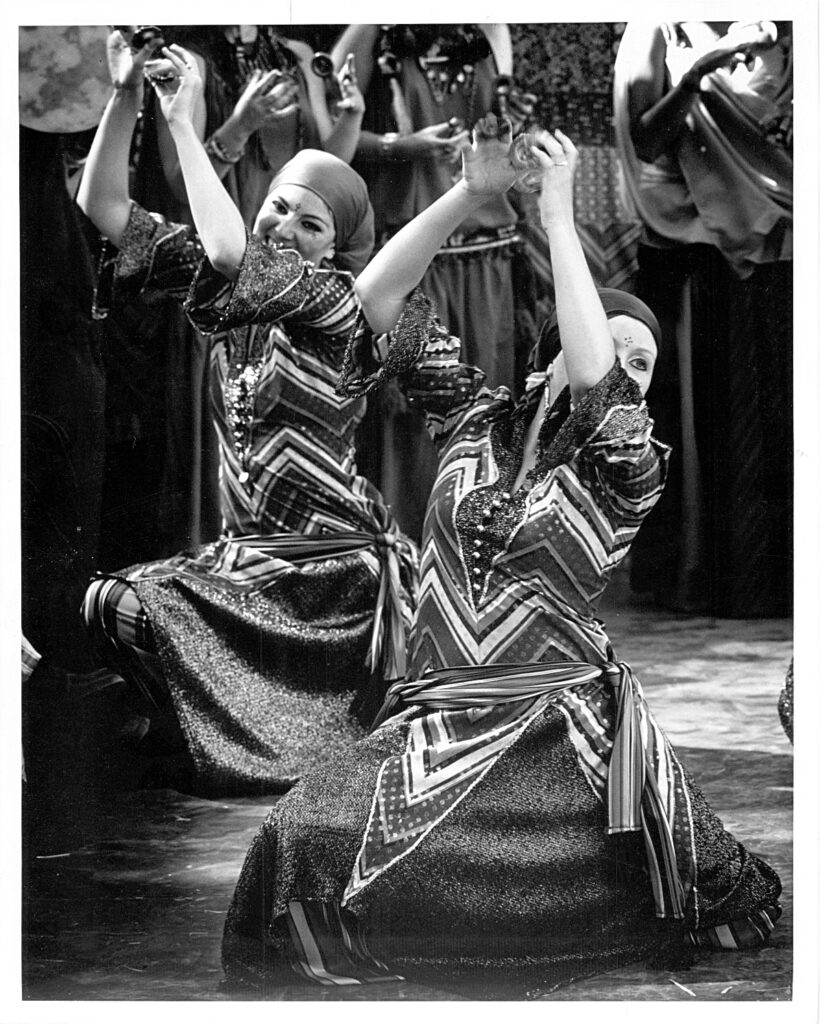

- Bal Anat Kashilama dancers.