Habibi: Vol. 10, No. 10 (1988)

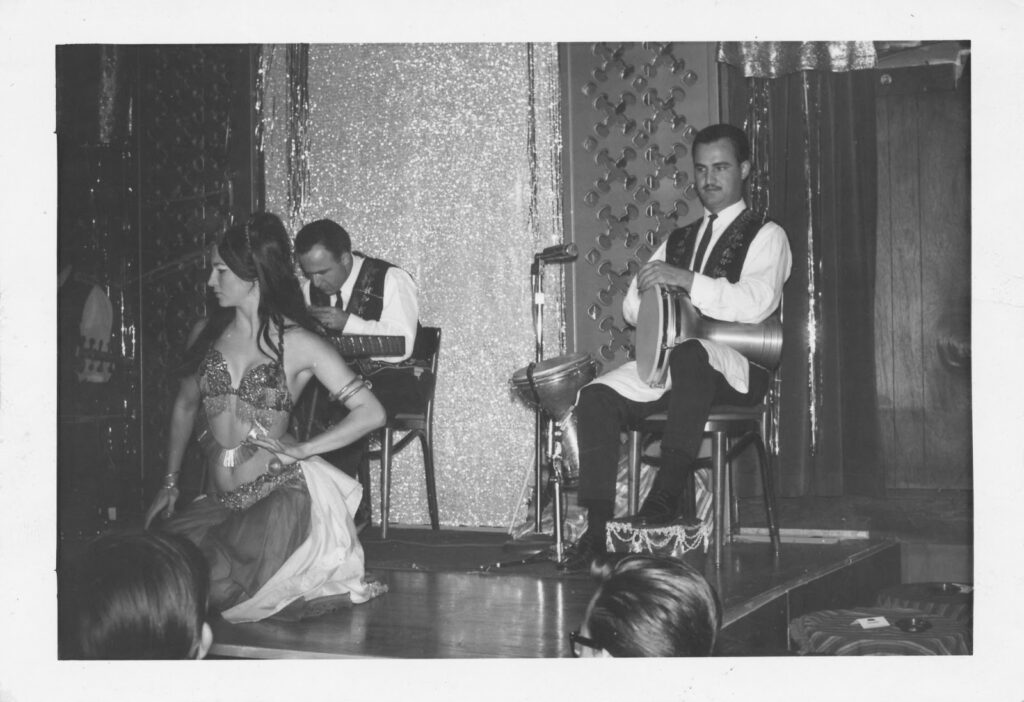

Although he worked as a drummer in an Arabic nightclub, my husband Ardeshir forbade me to play Arabic music in our house. He was Persian and only wanted to hear Persian music at home. We met while working together in an Arabic nightclub, but shortly after our marriage, certain hostilities surfaced for which I was not prepared. Regardless of the fact that when he met me I was a dancer, after marriage, he forbade me to dance. He knew I had been married before I met him, but after our marriage, he would accuse me of promiscuous conduct for not having been a virgin when I married him. And when I gave birth to a daughter he threatened me, among other things, never to play finger cymbals in the house or to spark any interest in her which might result in the possibility that she would follow in the footsteps of her mother. Since he was prone to violence, I tried not to anger him.

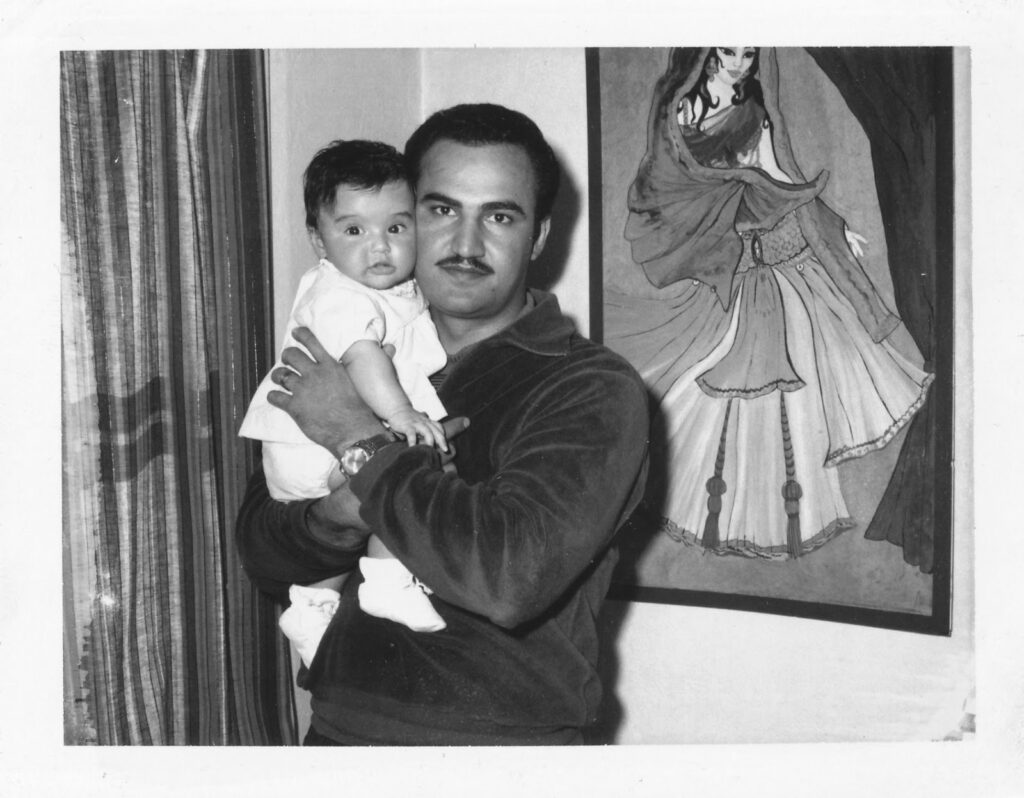

After Suhaila was born, I again wanted to contribute to the support of the house. For him my dancing in public was out of the question. Prior to Suhaila’s birth he would “allow” me to teach privately providing I removed all the evidence of music or costumes before he got home. It was the only means of livelihood I knew. I expressed the desire to teach again, and he exploded “Why don’t you do something respectful?” I asked, “Respectful?… Respectful?… What do you mean by, respectful?” “Something respectful” he would repeat over and over again. ‘”Oh,” I said, “You mean like working in an office or a bank?” He would bring the tips of his fingers up and together in the air and pull them down in a straight line which was sign language for, “Now do you understand?”

I wanted to please him. I wanted peace. I went out, looked for, and got a job in a bank within walking distance from the house. Luckily it was part-time to start with as Suhaila was about one month old. I would work four hours a day and still have time to come home and take care of the family chores. However, it wasn’t long before I realized that my daughter’s health was in jeopardy. Since my husband was confined to the house to watch the baby while I worked, he invited his friends over to socialize while he babysat. I would come home from work to find Suhaila in her crib which had been brought into the living room now filled with smoke. Persian music resounded from the speakers now turned to full volume as the men played cards and drank, barely noticing my entrance. After politely greeting them as befits a respectful Persian wife, I would wheel the crib out of the living room back into the bedroom and immediately change her diapers, which were excessively soaked through.

This couldn’t go on, I thought. But how could I quit my bank job without angering him? Luckily fate intervened before things got any worse. I had faked references to get the bank job, never thinking they would actually check. Well, they did. Four weeks from the day they hired me I was called into the personnel and told that my references didn’t check out and they would have to let me go. I was outwardly silent but inwardly elated. Now I had an excuse to resume teaching since, as I justified, I had no experience except as a dancer. So my husband allowed me to teach on the condition that there would be no trace of my profession in the house.

For the sake of time and space here let us just say that my husband was an angry young man. He was, most of the time, manic depressive, with more down swings than up. It was hard to believe he was the same person as I watched him clown with his male friends, joking and dancing, usually the center of attention. There were no battered women’s centers at that time and at first when Suhaila and I ran away, fearing for our safety, I called his best friend to tell him about the threats and danger I was experiencing. He didn’t believe me. The man I described was not his best friend. I was, he assured me, imagining everything. Anyway, I thought, I had informed his friend so he might act as moderator in any attempt at reconciliation, and for someone to be made aware that my domestic silence did not mean all was well. I was to run away two more times before his parents came to America, and we all moved in together.

There was much my husband disliked about the United States. He would say, “I don’t want my daughter to grow up here!” Although he and his friends went out carousing regularly, he disapproved of the excessive freedom he thought American women had. “Look at the way they dress,” he said, “like gende (whores)”. His mother would feign repulsion as she watched television. When a commercial using a model in a scanty dress or bathing suit came on she would avert her eyes and slap her face exclaiming, “Kaseefeh, Kaseefeh! (Dirty! Dirty!)” It was in this atmosphere of criticism that I began to suspect a plot.

Mostly Farsi was spoken in the house. My mother-in-law was determined to train Suhaila to be a good Persian girl so they began to dress her in a chador as she received instruction in reciting verses from the Qur’an. Every now and then I would get wind of something suspicious until finally my husband became angry with me over something or other and solemnly told me, “If some day you take Suhaila to school or the nursery, don’t be surprised if, when you come to pick her up, she is not there.” “What do you mean,” I asked. He replied, “I do not want her raised in this country. She will be better off with my relatives in Iran.” I froze. He was dead serious. He would say it more often when he was angry at me.

Secretly I went to the police and asked them what I could do to try to prevent this from happening. I was told they could do nothing. It was a story they had heard from other women, some of whose children and husbands had disappeared. There were many cases already. And so, I raised my daughter warning her never to agree to be taken out of school or nursery by anyone but me. Although the threat was never carried out, I lived with the fear that this nightmare could happen.

This article was published in Jamila’s Article Book: Selections of Jamila Salimpour’s Articles Published in Habibi Magazine, 1974-1988, published by Suhaila International in 2013. This Article Book excerpt is an edited version of what originally appeared in Habibi: Vol. 10, No. 10 (1988).

Photo Credits:

- Ardeshir Salimpour, Suhaila Salimpour’s father, drumming, in the 1960s.

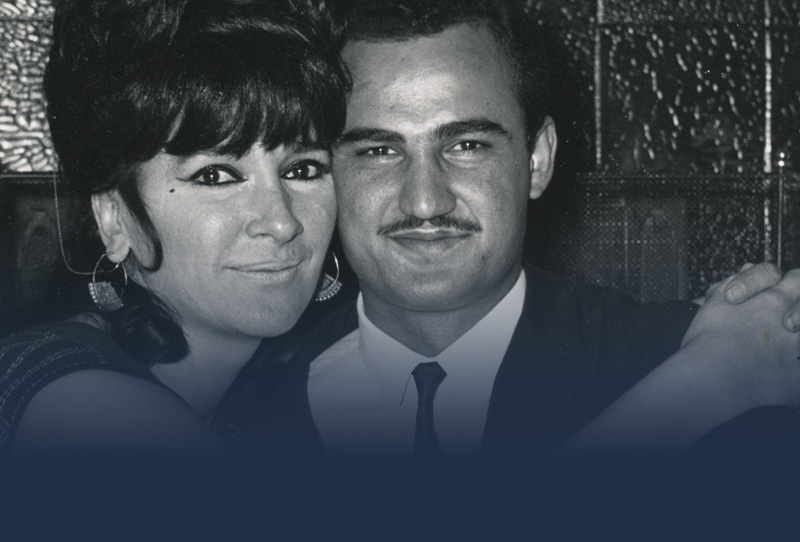

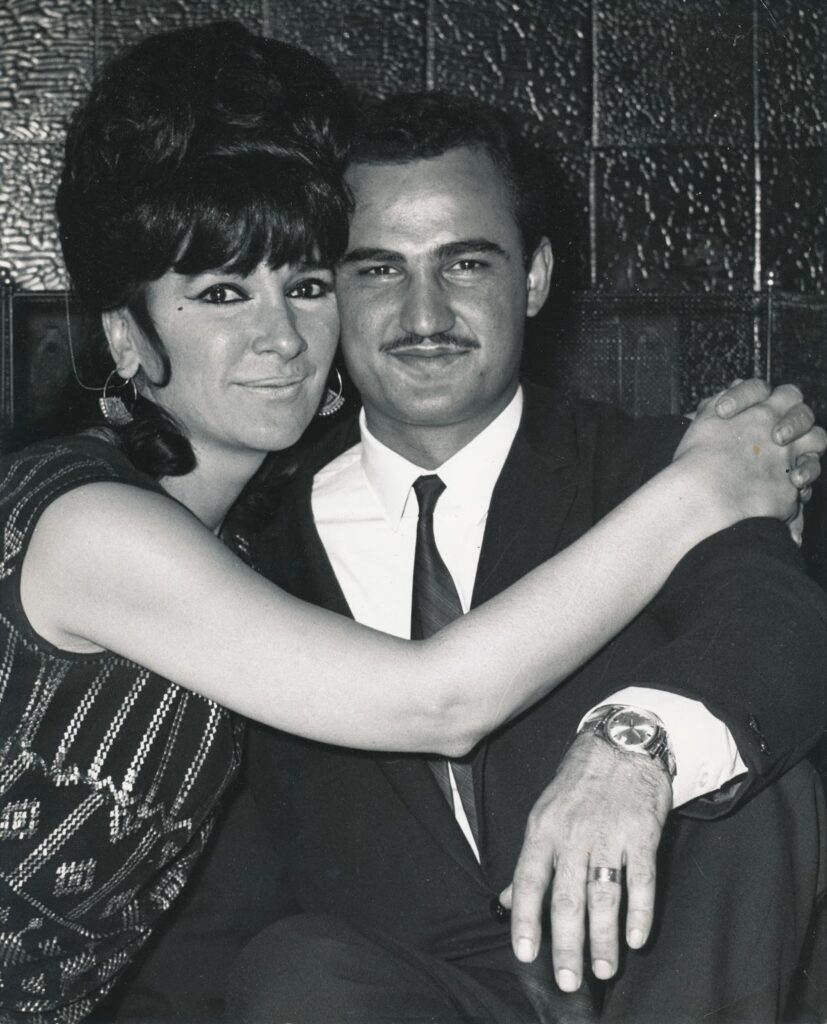

- Jamila Salimpour and Ardeshir Salimpour, circa 1966.

- Jamila Salimpour pregnant with Suhaila, May 1966.

- Baby Suhaila held by her father, Ardeshir, 1967.