Father of Costume Design

Habibi: Vol. 4, No. 3 (1977)

About the year 1951, I was spending some free time in one of my favorite ways: seeking out and browsing through used bookstores. They have always held intrigue for me with their unwashed windows supporting collectibles whose value is limited to esoteric fanatics in search of individual specialties. One such shop on Hollywood Boulevard boasted collections of theatricalia which had been acquired in affluence by actors and actresses who later sold them for the necessities of survival. I lingered and thumbed through a few books, but nothing caught my fancy. I was about to leave when I casually picked up a brown pamphlet on the top of a low stack near the door. The pamphlet turned out to be a program of the first American tour of the Ballet Russes under the direction of Sergei Diaghilev. As I thumbed through the pages I was astounded by the magnificence of the dancers whose action was rendered in patterns wrought into fabric and stitched into costumes which were a kaleidoscope of oriental splendor.

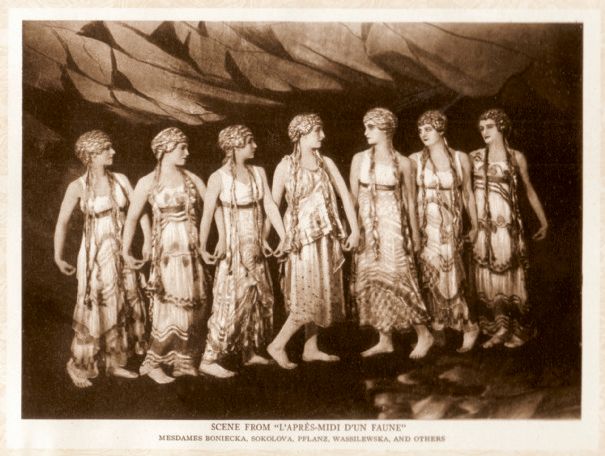

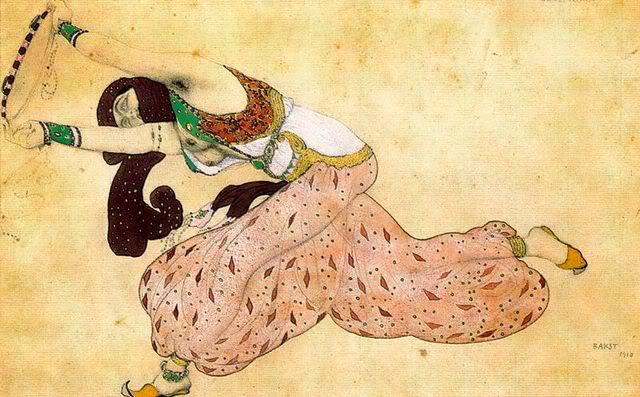

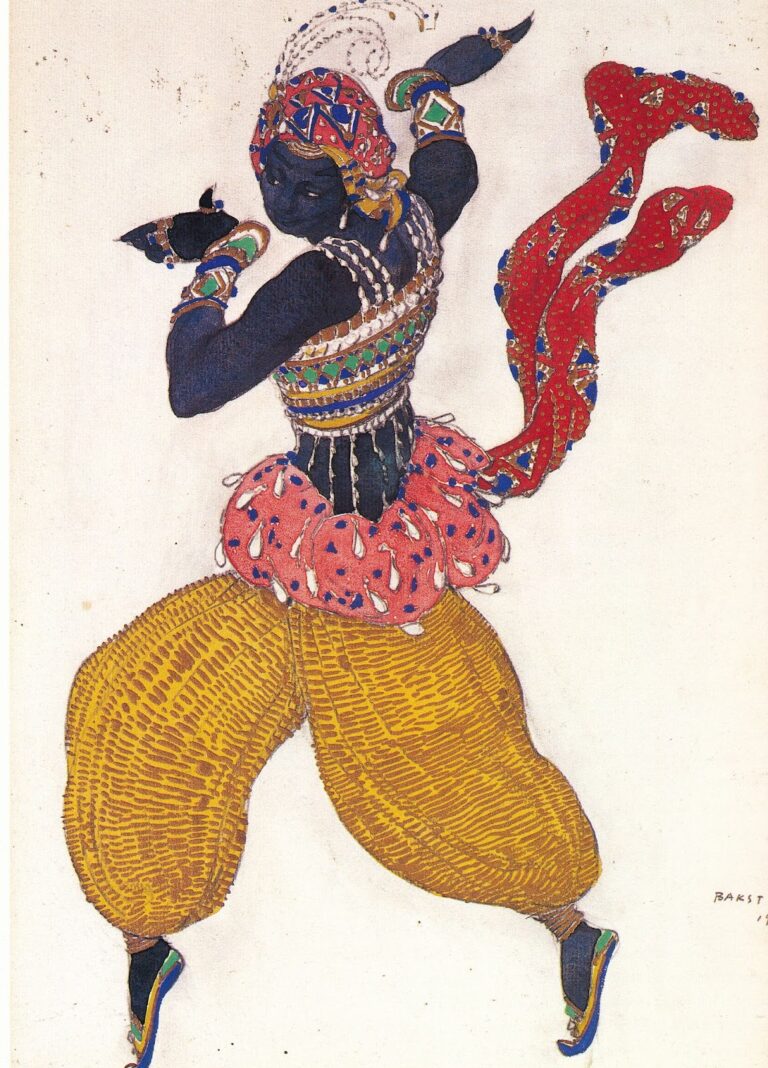

Who was this artist who seemed to concentrate on the sensuality of the Orient as he depicted bounding ballerinas dressed as bayaderes and divas draped as devadasis? The ballets presented were Scheherazade, Le Dieu Bleu, Cleopatra, Prince Igor, Afternoon of a Faune, Thamar, Sadko, and Les Sylphides—all on one program! A generation of geniuses united to resist the old front of the stagnant and stylized post-Victorian period. The Family, as they were referred to, boasted such names as Vaslov Nijinsky, Michel Folkine, Sergei Diaghilev, Jean Cocteau, Igor Stravinsky, and Pablo Picasso; some of the music which inspired them was by composers such as Frank Liszt, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, Igor Stravinsky, Alexander Borodin, Frèdèric Chopin, Richard Strauss, and Claude Debussy.

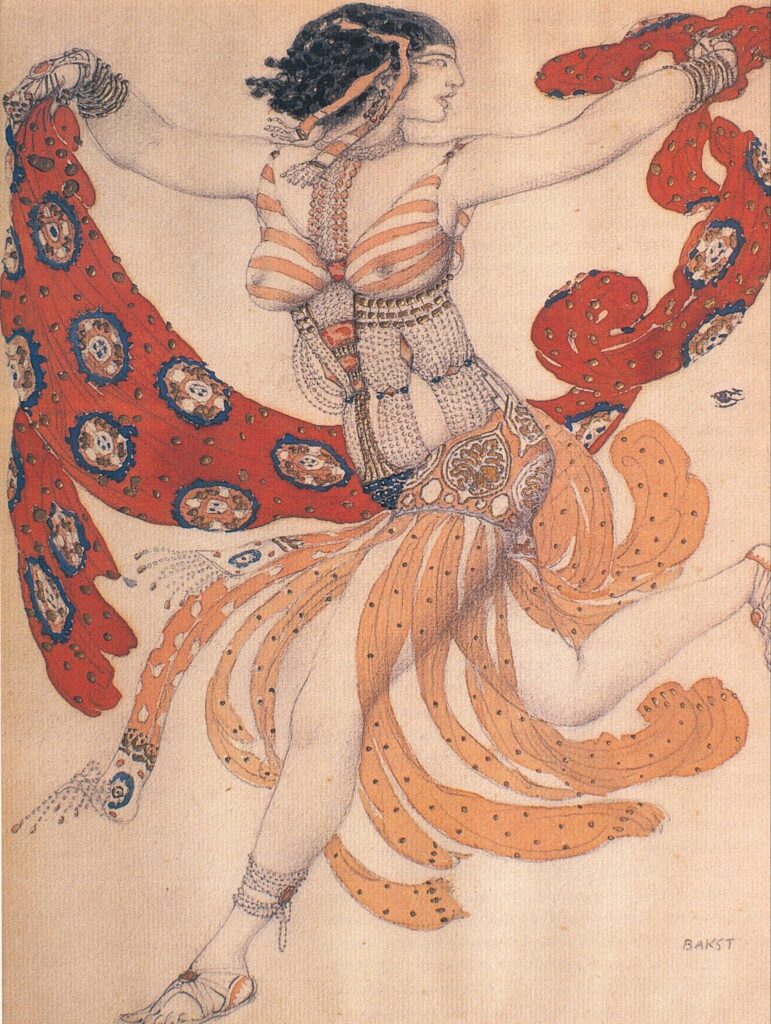

The color and artistic force of the Ballet Russes burst upon the stage in Paris at the turn of the century and eventually astounded Europe; it was brought to the United States in 1916. The costumes of Leon Bakst had such worldwide influence on the couturiers that every woman was determined to look like a slave in an oriental harem.

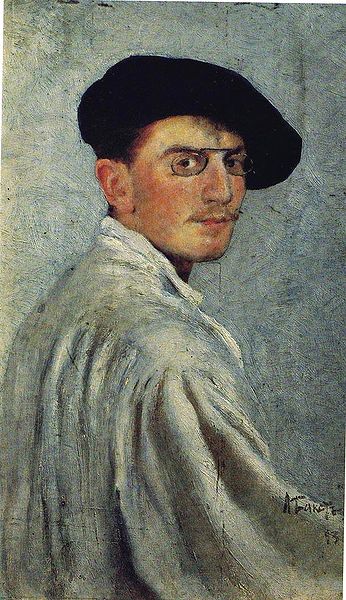

Leon Bakst was born in Russia in 1868. His fascination for orientalia was inspired by his grandfather who lived in an artificial paradise to which, as a young boy, he made weekly visits. At an early age, Bakst discovered the theatre, and he created miniature sets to entertain his little sisters. His productions were provided by the librettos of Verdi’s operas. He entered and won a drawing contest in school, much to the displeasure of his father, since his other studies were receiving bad marks.

As Leon persisted in his desire to pursue art, he persuaded his father to submit some of his sketches to a well known artist in Paris who replied favorably with the advice that the young boy attend the Paris Academy of Fine Arts. It was 1884, and Leon was sixteen years of age. In five years the Paris Exposition would take place with countries such as Egypt, Algeria, Turkey, and Persia participating. The grand spectacle, which drew visitors from all over the world, must surely have enticed him at such close range.¹

As we gaze over the drawings of almehs, odalisques, eunuchs, sultanas, and sultans, we can picture the drama behind the scenes as Sergei Diaghilev, who was the pivotal character (and, as it were, Svengali-like figure) who maneuvered and manipulated the performers into stardom. Diaghilev intended to become a composer or a musician but was finally convinced by Rimsky-Korsakov that he had no talent in either direction. He was, however, determined to make his mark. In his early life, he surrounded himself with artists and arranged exhibitions while also collecting antique furniture and works of art for wealthy and influential patrons throughout Europe.

Alexandre Benois, a prominent member of the “family” is credited with his enthusiasm for ballet which infected his friends and which eventually led to the formation of the Ballet Russes. Diaghilev, the master showman, was gifted with the administrative genius and ability to consolidate the powerful friendships which were to facilitate the creation of a permanent ballet company. Bakst designed costumes for Anna Pavlova and Nijinsky and lured them from the Imperial Theatre to Diaghilev. Fokine also was drawn into the creative circle. The beautiful Ida Rubenstein inspired Bakst to create an entrance for her interpretation of Cleopatra which would have impressed Cecil B. DeMille. Cocteau describes it:

Balanced on the shoulders of six stalwarts, a kind of chest of gold and ebony was borne aloft. A negro youth kept circling about it, making way for it, touching it, urging on the bearers in his zeal. The chest was placed in the centre of the Temple, its doors were opened and from it was lifted a kind of glorified mummy swathed in veils, which was placed upright on ivory pattens … Four slaves subjected it to marvelous manipulations. They unwound the first veil, which was red throughout with lotuses and silver crocodiles; the second which was green with all the histories of the dynasties, in golden filigree upon it; the third which was orange shot with a hundred prismatic hues and so on until they reached the twelfth, which was of indigo, and under which the outline of a woman could be discerned. Each of the veils unwound itself in a fashion of its own: one demanded a host of subtle touches, another the deliberation required in pealing a walnut, the third the airy attachment of the petals of a rose, and the eleventh, most difficult of all, came away in one piece like the bark of the Eucalyptus tree. The twelfth veil of deep blue revealed Madame Rubinstein, who let it fall herself with a sweeping circular gesture, and stood before us perched unsteadily on her pattens, bent slightly forward with something of the movement of the Ibis’s wings…on her head she wore a little blue wig, with short golden braids on either side of her face, and so she stood with vacant eyes, pallid cheeks, and open mouth, before the spellbound audience, penetratingly beautiful like the pungent perfume of some exotic essence. ²

Charles Spencer wrote:

The origin of almost all of Bakst’s work for the Ballet Russes is to be found in the works of Mikhail Vrubel. Bakst in his designs for themes such as Sadko, Cleopatra, Thamar, Istar, Solome, Scheherazade and Daphnes Et Chloe, found an outlet for his explosive temperament which alternated between a creative energy drive with periods of depression and imposed isolation. In his preference for Middle Eastern themes splashed with sensationalism, Daghileff created Oriental essays in sex and violence. It all began with Scheherazade, the greatest success in the history of the Ballet Russes, and probably modern ballet; certainly the most sensational exercise in modern stage design. It succeeded because its source of inspiration, Diaghileff and Bakst, were able to satisfy their personal fantasies in a manner sufficiently exciting to involve almost anyone. The tale of a harem of beautiful women using the absence of their lord and master to indulge in an orgy of group sex with a band of muscular negroes, ending in a bloodbath of vengeance, was – and is- infallible with the public. It examined and illustrated the sexual fantasies of virtually every man and woman in the audience, whether heterosexual or homosexual, and for good measure satisfied their moral standards by insuring that the culprits were punished, thus providing both pleasure and correction.

Bakst lived in an era where his presence created the illusion of the sumptuousness of the Orient in the European circles in which he traveled. One of his patronesses, the Marchesa Casati, was resplendent in Scheherazade-like costumes in her home. On occasion she was accompanied by a black Tunisian Prince, a panther, ocelots or an Afghan hound. Isadora Duncan, when she visited her in Rome, found one salon lined with tiger skins, another with white bear rugs, and in a third a live gorilla.

Leon Bakst captured the splendor of the Middle East and is rewarded by being best remembered for his voluptuous illustrations of the Classical Oriental dancers which he drew and who, even now as we gaze upon them, are caught in a moment of action but will continue dancing if we will but close our eyes.

This article was published in Jamila’s Article Book: Selections of Jamila Salimpour’s Articles Published in Habibi Magazine, 1974-1988, published by Suhaila International in 2013. This Article Book excerpt is an edited version of what originally appeared in Habibi: Vol. 4, No. 3 (1977).

¹ Andre Levinson, Bakst: The Story of the Artist’s Life (New York: Benjamin Blom,1971).

² Arsene Alexander, The Decorative Art of Leon Bakst (New York: Benjamin Blom, 1970).

³ Charles Spencer, Leon Bakst (London: Academy Editions, 1973)

Bibliography

Bakst, Leon. Bakst. New York: Rizzoli Press, 1977.

Photo Credits:

- Costume design for the ballet Cleopatra, Leon Bakst, 1909, Public Domain. https://www.wikiart.org/en/leon-bakst/costume-design-for-the-ballet-cleopatra-1909-1

- Costume design for the ballet Scheherazade la sultane bleue, 1910, Leon Bakst, Public Domain. https://www.wikiart.org/en/leon-bakst/scheherazade-la-sultane-bleue-1910

- Chorus of maenads. Photograph 1912 by Adolf de Meyer from the 1914 book Nijinsky: L\’Apres-midi d\’un Faune, Costumes de Léon Bakst, Public Domain.

- Self portrait, Leon Bakst, 1893, Oil on cardboard, The State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia, Public Domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bakst_self.JPG

- Costume Design for Scheherazade, 1910, Leon Bakst, Public Domain. https://www.wikiart.org/en/leon-bakst/costume-design-for-scheherazade-1910

- Mme Ida Rubinstein as Cleopatra, Press Photograph, 1922, Unknown photographer, Public Domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ida_Rubinstein_1922.jpg

- Costume design for a dancer Nègre Diamanté: costume design for Scheherazade, 1910, Leon Bakst, Waddesdon, The Rothschild Collection (Rothschild Family Trust, Public Domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Scheherazade_by_L._Bakst_13.jpg