Habibi: Vol. 3, No. 8 (1976)

“Belly Dancing”… is that its historical name? Does it have a history? When did it originate and how did it evolve? Is it a folk dance or is it a professional woman’s dance that requires training and skill? What, if any, are the significance of its movements? Was it performed by a special class of women? How has the dance changed since its origin? These and many other questions went around in my head since I first became interested in oriental dance, but finding answers was difficult for a number of reasons. To look for specifics, one has to know what to look for.

In researching belly dancing, few passages in books are found except a few vague, usually incorrect statements or probabilities. Or, what is worse, judgments as to the validity of the dance form as an acceptable art. Visitors to the Middle East have often written of their travels but very few have given accurate descriptions of the dances they saw. How could they? They were not trained to look from a dancers point of view.

Often, Europeans with a curiosity of the Orient, but with their head and heart in the Occident, would reject anything foreign as barbaric. The rare case was the visitor who learned the language and assimilated the culture by living in the culture. Mostly too, the visitor was more interested in the architecture of antiquity and biblical settings. There was also a curiosity about oriental splendor and, of course, polygamy and harems. Looking for information on the origins of belly dancing was slow, if next to impossible. Brief speculations as to how the ancient Egyptian dances were performed were found, but no written word in length; no entire dance was to be found. A pose here, a posture there, but nothing like the posture statues which record the living tradition of the dance of South India, Bharatanatyam. I tried to find out by various methods what the dance was all about. No one knew. A few people made guesses. I was resigned to a state of confusion and mixed feelings until a dancer by the name of Helena Kallianiotes gave me a booklet reprinted from Dance Perspectives in 1961 which had two articles in it and, most important, a bibliography for the beginning of serious research.

“Belly Dancing”: What is the conditioned image that is brought to mind with that phrase? Usually, it is the interior of a sumptuous palace. A bejeweled pasha, sultan, lord of some kind is reclining on a divan covered with pillows. At his feet lie dozens of beautiful women in magnificent oriental costumes all looking in his direction. The sultan nods his head and a eunich claps his hands two times, the signal to bring on the dancing girl. Her costume is scanty. Her dance is passionate and uninhibited. Her focus is entirely directed on the sultan, pasha, lord, whatever, and her dance is frustrated sexuality that can only be relieved by him. This is the stereotypical fantasy that has come down to us through the present day.

In Hollywood movies the harem dancer was always a brooding beauty who helped studios recoup from box office slumps. Ever since the movies of actor Rudolph Valentino, studios felt that the dancer was an escape for both sexes in the United States. The female was the odalisque, knowledgeable but submissive, seeking only to please. The male was dominant and determined. Yvonne De Carlo, Rita Hayworth, and Maureen O’Hara were a few of the unconvincing inmates of the harem. Oh, the excessive make-up and, of course, they always lived happily ever after.

Undoubtedly one of the greatest boons for propaganda of the sensuality of the Middle East and anything that went along with it was Rudolph Valentino. The silent film era produced many stars who swashbuckled across the screen, but Rudolph was always in the limelight. In his film, The Son of the Sheik (1926), his character falls in love with a dancing girl, played by Vilma Bánky, who falls in love with him in return. His father protests but his mother, an Englishwoman, reminds the sheikh of her own abduction by him and the father chuckles and submits to a “like-father, like-son” decision at Rudolph’s independence in choosing his own mate. The lovers ride off into the desert on his steed. When Rudolph Valentino died, an era of oriental faddism came to a close never to be revived again in the adoration of a single male, who was a pseudo-Arabian sex symbol.

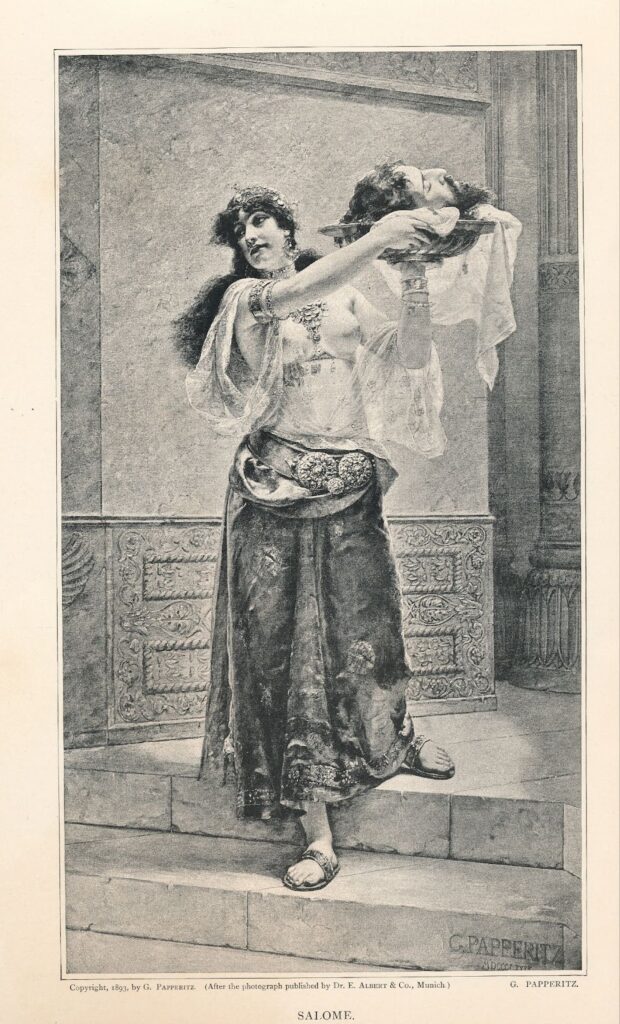

The dance as performed in Arabic nightclubs is nothing like the imitation ‘’harem” dance usually performed by an untrained starlet in Hollywood movies. The stereotype of the secluded beauty who was compelled to dance for a repulsive villain prior to her rescue by the hero was one step above Our Gang comedies as far as authenticity was concerned. Hollywood ground out one film after another. One showed Maria Montez in oriental opulence searching for the poor but handsome poet philosopher, who was a real prince in disguise. Turhan Bey in a close-up was every woman’s dream, he of the twitching mouth and flaring nostrils. The musical accompaniment was as “authentic” as the dance. Hollywood casting directors did not bother to authenticate or duplicate the “real” thing. Probably they thought it would be too grating on American ears; besides, it was the fantasy that counted. Starlets posed for publicity shots as the bawds of the Bible (Tais, Tamar, Salome), it being assumed incorrectly that the dance, seduction, and destruction went together. Western women fantasized about their princes on horseback and magic carpets.

Around the late 1930’s or early 1940’s, a woman by the name of Khanza Omar migrated to Hollywood and somehow worked as a movie extra. Legend has it that she was a Moroccan princess. She had danced for Arab functions and was commissioned to instruct stars such as Yvonne De Carlo. Either they were not good students or there was a problem in communication, but it was performances such as these which convinced an unknowing public that to be a Middle Eastern dancer all you had to do was put on an appropriate costume and do almost anything that came into your head. The instruction and resulting technique were altogether lacking in ethnic credibility.

This article was published in Jamila’s Article Book: Selections of Jamila Salimpour’s Articles Published in Habibi Magazine, 1974-1988, published by Suhaila International in 2013. This Article Book excerpt is an edited version of what originally appeared in Habibi: Vol. 3, No. 8 (1976).

Photo Credits:

- Salome, By Georg Papperitz, 1890, Woodcut Engraving. Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Glaspalast_M%C3%BCnchen_1890_175.jpg

- Lobby card for the American film The Son of the Sheik (1926), United Artists. Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Son_of_the_Sheik_(1926_film)_card2.jpg

- Rudolph Valentino and Vilma Banky in The Son of the Sheik, 1926, J. Willis Sayre Collection of Theatrical Photographs. Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Rudolph_Valentino_and_Vilma_Banky_in_%22The_Sheik%22_(SAYRE_4629).jpg

- María Montez and Jon Hall in Arabian Nights – publicity still, 1942, Universal Pictures. Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Arabian_Nights_(1942)_1.jpg

- Publicity photo of Claudette Colbert for the film Cleopatra, 1934, Paramount Studio, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cleopatra_publicity_photo.jpg

- Claudette Colbert in the film Cleopatra, 1934, Paramount Studio, Vintage print from Jamila Salimpour Danse Orientale Archives. No known copyright restrictions. Image in article; we can’t find original; if it’s not needed, don’t worry about using this image